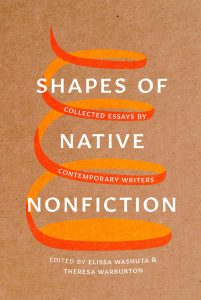

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This Fourth of July, we celebrate Native American culture and literary traditions, with an interview with Elissa Washuta, a member of the Cowlitz Indian tribe, and Theresa Warburton, from the Lummi/Coast Salish territory, editors of the recently published Shapes of Native Nonfiction: Collected Essays by Contemporary Writers.

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

ELISSA WASHUTA: I think it was probably The Tattooed Potato and Other Clues by Ellen Raskin. It was one of the first chapter books I read, a 1975 YA novel about an art school student named Dickory Dock who goes to work with a painter who is involved in some seriously mysterious business. I returned to it a lot because of its strangeness, but also because its mystery was driven by the characters and their secrets as much as by the happenings of the plot. I reread it as an adult and found it didn’t enchant me in the same way because of its ableism. As a child, I don’t think I’d ever read a book like that, in which I, as a reader, was invited to do so much work to tease out meaning and wait patiently for answers.

THERESA WARBURTON: I think the one I remember most strongly is Charles Bukowski’s Love is a Dog From Hell, which I am sort of loathe to admit. I feel like, in the punk circles I was in, Bukowski was a really towering literary figure so I felt a pressure to know and read him. It’s the first time I remember thinking about being ugly on the page, about literature being about something other than creating some idyll even if it was tarnished. But the one poem that still lives inside me is a poem he wrote for a woman named Frances. And, in that poem, he has this moment of weird lucidity where he recognizes what an ass he is for patronizing this woman who has cared for him and who he’s mocked for believing in a better world. At the end of the poem, he says “she has hurt fewer people than / anybody I know, / and if you look at it like that / well, / she has created a better world / she has won.” And I still think, to this day, that I’d like to be the kind of person that could be described that way, even if it’s by someone like Bukowski.

2. What role does form play in how you shape the truth, as an editor and/or as a writer?

WARBURTON: I’m not sure that I think that often about truth, per se. I think about the ethics of how we attain and process information and the tools we’re given to do those things. To me, all stories have a form and that’s connected to their ethical intervention in the world. When I work with students, I try to give them the tools to identify the shape of the writing and then, from there, to understand how that shape is meant to carry the contents, what it’s trying to tell us. So, as an editor, I wanted to be sure that we were honoring the form that the authors imagined for their pieces, since asking them to change that would mean asking them to change the ethical root of their work. As a writer, I try to keep my ethical commitment at the forefront of my mind when thinking about how I shape the story I’m telling. This has been important to me in my academic writing and has meant that I think a lot about the structure of what I write.

WASHUTA: As an editor, I share Theresa’s approach. As an essayist, I feel strongly about veracity in my own writing, not so much because of my responsibility to deliver facts to the reader, but because of the ways the truth forces me into spaces that are uncomfortable and therefore productive. I like to make problems for myself on the page and answer them using formal moves. The problems are usually questions: How do I figure out why I did/felt/wanted this? How do I communicate this feeling to the reader and create a reproduction of my own experience of it? By chopping and splicing the timeline, or pouring the recounting into a formal container it didn’t come in.

“To me, all stories have a form and that’s connected to their ethical intervention in the world.”

3. What does your editorial process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

Our process was driven by pure enthusiasm for these essays and the drive to make something that would respond to a need in Native literature. It was easy to work with these essays because we loved them so much, and every one served as a source of renewal for us when we struggled with our other projects.

Our editorial work was mostly done through text messages, Google docs, and emails, as we never lived in the same city and only had a couple of in-person work sessions to shape the book’s concept early on. We identified writers and previously published essays that were doing the sort of work we wanted to gather, wrote a book proposal that established the concept and outlined the need for such a book, requested permission to reprint essays and solicited new work, put the essays in order, and wrote an introduction to guide the reader through the work. We went through peer review and revised. There were so many small and large tasks that went into the making of the book, and a skilled team at UW Press also did a lot of work on it, but that’s the basic flow. In all of it, we tried to be really deliberate about how we were dividing up the work and what kinds of work we should each be responsible for. Having an established and open practice of communication was absolutely essential, so in that way, building and maintaining our relationship was an important part of the editorial process as well.

4. How can Native and non-Native writers affect the process of decolonization?

It’s important to us to begin by not assuming that the definition of decolonization is widely understood, because while its usage is becoming more common, notions of decolonization divorced from Indigenous peoples are missing the mark. In “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor,” Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang write, “decolonization specifically requires the repatriation of Indigenous land and life. Decolonization is not a metonym for social justice.” This means that increasing diversity in publishing is not decolonization, and non-Natives writing about Native issues and peoples is not decolonization. Decolonization requires that the colonizer cede usurped lands and power structures to Native peoples in service of Indigenous sovereignty.

The work of Native writers is part of this because of its role in continuing Indigenous epistemologies and in building Indigenous futures. For non-Natives, decolonization is less possible in their own work than it is in their adjacent roles: as editors, for example, or as educators. When they serve as gatekeepers, they set the agenda. As Tuck and Yang write, “decolonization is not accountable to settlers, or settler futurity. Decolonization is accountable to Indigenous sovereignty and futurity.” Non-Native editors are not decolonizing when they publish Native writers in their literary journals or when they assign reviews of books by Native writers. These are good things to do, but decolonization requires that Native writers set the terms, and that non-Natives cede power, authority, and influence.

Decolonization requires that non-Natives actively move out of the way of the continuance and expansion of Native knowledge. And it requires that non-Native people be accountable to the land and its people and to take that responsibility seriously—that needs to be put above accountability to editors, investors, trustees, or other stakeholders.

5. Tell us about your favorite bookstore or library.

WASHUTA: I’ve lived in Columbus, Ohio, for the last two years, not far from Two Dollar Radio HQ, the bookstore and cafe operated by the press of the same name. They’ve got a small but really well-chosen selection of mostly independently published books, and they host great events and have a few book clubs. I love that they’re intentional about serving the community, not just for greater Columbus, but specifically for the southside, where they’re located. Eric, Eliza, and Brett put a lot of care into creating a welcoming meeting place, and they’re great about offering the space without dictating the shape of the programming.

WARBURTON: My favorite bookstore is Burning Books in Buffalo, NY. They always have the most well-curated, thoughtful collection of radical books and zines but it is also such a community-centered space. I’ve organized and seen great events there, from activist talks to book readings to film screenings. They also gave the Buffalo Prison Abolition Reading Group a warm home. You can feel the care that Leslie, Theresa, and Nate put into the store and into the community. And if you get a chance to buy some of Leslie’s grandmother’s blueberries when they’re in season, you’ll be able to taste how special the place is too.

6. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

WASHUTA: NDN Coping Mechanisms, Billy-Ray Belcourt’s incredible second book, coming out in September. Next, I’m reading The Crying Book, Heather Christle’s forthcoming book. Both of them are excellent writers of both poetry and nonfiction!

WARBURTON: I just finished reading an advanced copy of Junauda Petrus’s The Stars and the Blackness Between Them, which was incredible. I hope everyone reads it. I’m also in the middle of reading Indigenous Literatures from Micronesia, which is a collection edited by Evelyn Flores and Emelihter Kihleng, and Keri Hulme’s The Bone People since I’m doing some traveling through the Pacific right now. I always like to read something connected to the land and people as a way to try to be a good visitor.

“Your work is worthy of being what you want it to be.”

7. What advice do you have for young indigenous writers and editors?

WASHUTA: Don’t let the publishing industry define how you feel about yourself and your writing. The times I’ve been the most miserable as a writer are the times when I’ve been trying to write what editors told me they wanted from me but what I really didn’t want to write, like my brief period working on a novel because my memoir-in-essays wouldn’t sell. I’ve been happiest when I stuck with my commitment to my own stylistic and structural approaches and developed as a writer inside my own intentions. The other times I’ve been the most miserable are the times I’m deciding I’m not succeeding because I’ve been measuring myself against other writers and their exposure and feeling that I don’t have enough skill or enough recognition. Get that envy stuff out of you as quickly as you can. I have a couple of trusted friends I talk to when I’m feeling jealous. We diffuse our jealousies together and let the feelings die when we air them. We need to be good to each other. The more I champion the work of others, the better things get for me.

WARBURTON: Your work is worthy of being what you want it to be.

8. Which indigenous writers working today are you most excited by?

Everyone who appears in the book, of course, but also, there are many Indigenous writers whose nonfiction we didn’t become familiar with until after we’d finished gathering the work, and many who don’t write nonfiction. So, in addition to the Shapes contributors, we’ll add Lindsay Nixon, Danielle Geller, Demian DinéYazhi’, Joshua Whitehead, Tommy Pico, and Gwen Benaway.

We also want to expand how we think of writing to include all kinds of storytelling, like the amazing work being done by artists like Jeremy Dutcher, Tanya Tagaq, and Katherine Paul (from Black Belt Eagle Scout).

9. Why do you think people need stories? Why do we need essays?

It’s not exactly that we need stories—we are stories. We are part of the stories that make up this place and so it’s our responsibility to make space for those stories, to tell those stories when they should be told, and to keep some stories when they shouldn’t. We compulsively narrativize the happenings of our lives and, in making personal meaning by connecting events and people and places, we live nonfiction. Plot is a stringing-together of events in consequential relationships, and it drives our lives, placing them within stories and stories within them. Essays are a way of telling stories and are part of the web of relations, of kinship, that are the stories that form our worlds.

10. Your collection, Shapes of Native Nonfiction: Collected Essays by Contemporary Writers, is ingeniously arranged according to weaving techniques used in basket making. How did you decide to arrange the collection around this art, and how did you distill the process into the four sections: technique, coiling, plaiting, and twining?

10. Your collection, Shapes of Native Nonfiction: Collected Essays by Contemporary Writers, is ingeniously arranged according to weaving techniques used in basket making. How did you decide to arrange the collection around this art, and how did you distill the process into the four sections: technique, coiling, plaiting, and twining?

Elissa is the one who first brought up the form of the basket as structure for the book. We were really interested in breaking down some of the assumed divisions in popular narrations of Native storytelling, especially materiality, orality, and literature. These things are often talked about as if they are completely separate, rather than related practices that aren’t so easily distinguished. The basket was an important way for us to emphasize this, by insisting that the basket is not a metaphor for the way we’re talking about form but actually is an example. We felt like structuring it this way made the argument more obvious on the page, in the form of the collection itself. Essay form can be difficult to explain without examples to point to. The relationship between craft, form, and content is so evident in a material object like a basket, so that helps us draw attention to the shape of stories and the shapes that stories give to us when we look at nonfiction.

Theresa Warburton lives in Lummi, Nooksack, and Coast Salish territories in Bellingham, WA. She is an Assistant Professor of English at Western Washington University, where she is also Affiliate Faculty in Canadian-American and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies.

Elissa Washuta is a member of the Cowlitz Indian Tribe and a nonfiction writer. She is the author of Starvation Mode and My Body Is a Book of Rules, named a finalist for the Washington State Book Award. She has received fellowships and awards from the National Endowment for the Arts, Creative Capital, Artist Trust, 4Culture, and Potlatch Fund. Elissa is an assistant professor of creative writing at the Ohio State University.