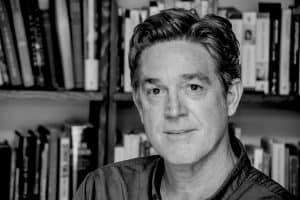

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week Ken Chen, executive director at the Asian American Writers’ Workshop, speaks to historian, journalist, and playwright Jeff Biggers, whose book, Resistance: Reclaiming an American Tradition, was published this year by Counterpoint.

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week Ken Chen, executive director at the Asian American Writers’ Workshop, speaks to historian, journalist, and playwright Jeff Biggers, whose book, Resistance: Reclaiming an American Tradition, was published this year by Counterpoint.

1. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity”?

My new book looks at the role of writers—writers of resistance, in many respects. Revolutionary author Thomas Paine, who published poetry, parables, short stories, songs, as well as news stories in his Philadelphia magazine, declared the “universal empire is the prerogative of the writer.” He added for good measure: “The Republic of Letters is more ancient than monarchy.” I’d agree with that. In the mid-19th century, African-American writer Maria Stewart methodically embraced her role as a writer of the resistance, publishing essays—not sermons—and performing them in counterspaces that had been reserved for white versions of abolition. “O woman, woman! upon you I call,” Stewart appealed, “for upon your exertions almost entirely depends whether the rising generation shall be anything more than we have or not. “

2. In an era of “alternative facts” and “fake news,” how does your writing navigate truth? And what is the relationship between truth and fiction?

Gene Roberts, the former reporter and editor of the NY Times, who covered the civil rights movement on the heels of the African American press, sought to bring the truth out of the shadows—to write about it so candidly and so repeatedly, as he noted in his book Race Beat, “that white Americans outside the South could no longer look the other way.”

3. Writers are often influenced by the words of others, building up from the foundations others have laid. Where is the line between inspiration and appropriation?

A fine one. I write about Henry David Thoreau being inspired by Native American author and activist William Apess, who went to jail in defense of the Mashpee community on Cape Cod in the 1830s and effectively framed an early version of civil disobedience. Reclaiming Apess’s critical role for me was vital in recognizing unaccredited ideas.

4. “Resistance” is a long-employed term that has come to mean anything from resisting tyranny, to resisting societal norms, to resisting negative urges and bad habits, and so much more. It there anything you are resisting right now? Is your writing involved in that act of resistance?

I view “resistance” through a fairly broad lens, beyond the requisite protest and petition, and ultimately as part of our American credo to fend off attacks on democracy: Reclaiming the public commons, providing a “truth and reconciliation” commission of stories that confronts the erasure of certain histories in our chronicles—what I term “historicide”—and re-peopling our histories in a more honest and compelling account of “we the people,” serving as an agency of renewal—these are all elements of resistance today.

In dealing with the most challenging issues of every generation, resistance to duplicitous civil authority and its corporate enablers has defined our quintessential American story. In truth, for anyone who believes in democracy, we’re all in the resistance now.

“In truth, for anyone who believes in democracy,

we’re all in the resistance now.”

5. What do you consider to be the biggest threat to free expression today? Have there been times when your right to free expression has been challenged?

One of my chapters looks at the ramifications of the Sedition Act of 1798, when it was a crime to “write, print, utter or publish, or cause it to be done, or assist in it, any false, scandalous, and malicious writing against the government of the United States, or either House of Congress, or the President.” Courageous journalists led the resistance, as noted by Jefferson, that “arrested the rapid march toward monarchy.”

6. What’s the most daring thing you’ve ever put into words?

My book was inspired by my 12-year-old son, who asked if there was any hope in an age of Trump, an age of climate change. I’ve written eight books of cultural history and hundreds of stories, but my son’s question made this book as about as daring as anything I could attempt.

7. Have you ever written something you wish you could take back? What was your course of action?

That’s why we have paperback versions—to correct our errors!

8. Post, stalk, or shun: What is your relationship to social media as a writer?

Reluctant poster.

9. Can you tell us about a piece of writing that has influenced you that readers might not know about?

I read poetry every morning before I get to work on my narrative nonfiction and theater projects. And I am reminded every morning of the still possibility of wonder.

10. If you could require the current administration to read any book, what would it be?

The Constitution would be nice, for starters.