The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Natalie Desroisers, the programs and communications assistant at Cave Canem Foundation, speaks with Geffrey Davis, author of Night Angler (BOA Editions, 2019). Join Geffrey Davis on October, 17, 6:30pm at The New School for a new works reading alongside Camonghne Felix and Ladan Osman.

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

I can’t remember which happened first—because we moved around so much, I struggle some with the timeline before I was 10—but a grade school teacher gave me the book Bridge to Terabithia by Katherine Paterson. I felt so heartbroken and somewhat betrayed by that book’s central loss (which I never saw coming) that I almost refused to finish the book. I forget what or who compelled me to keep reading, but I’m (mostly) glad that I did. Another grade school teacher read aloud the book Where the Red Ferns Grow by Wilson Rawls and I wept in class, embarrassed. As an adolescent I reread that book, certain it was youthful innocence that had affected me so much. I cried even harder the second time!

2. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

While I happen to pull almost exclusively from autobiographical material in my own work, I suspect that navigating a poem’s relationship to its truth or its fiction has to do with an artist’s best hunch about establishing the most critically and emotionally accurate (or honest) range to the subject. Each approach can fail the subject, though I have less experience with fiction. Sometimes we don’t yet have healthy enough traction or safe enough distance to publicly grasp with a lived truth in our voice. But also, in a way, I think the real evolution of my writing began with a fiction, with challenging myself to claim some things that weren’t yet true in my life—perhaps, most simply, that I was living a good life, fully and to its undetermined end.

” . . . the elasticity required of reading and writing poems has the potential to sharpen and/or transform the nature of our voices and hands, how they engage other people and ourselves.”

3. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

Like many, the major commitments in my life—as a parent, a partner, a mentor, a sibling, a child, a friend—I often feel in competition when it comes to my time. That, and it’s hard for me to move on once inside any one of those connections, because I feel faith in and enjoy trying to be as radically present with the particular poignancy of each point of contact. And they all matter. So I tend to organize my days around those connections and then, if an image or a question or a line or maybe a texture seems curious or urgent or distracting enough to interrupt how I’m making my way toward whomever, I try to honor that, to trust it and get to the page to begin the record of what’s going on in my head/heart. Then, the poem stays in my back pocket or my bag (to cut down on the traffic of getting to it) and maybe 75 percent of the poem gets revealed through revision, over time, consideration after consideration, until the piece turns on me and stops resisting the high order questions. And if ever I don’t have the time, rather than feel a way about it, I try to be grateful and move on, trusting that I’m still doing the good work and that another poetic pull on my attention is on its way.

4. Whose words do you turn to for inspiration?

I have Sean Thomas Dougherty’s poem “Why Bother?” (from The Second O of Sorrow) taped to my office door. It reads in its entirety:

Because right now there is someone

Out there with

a wound in the exact shape

of your words.

5. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

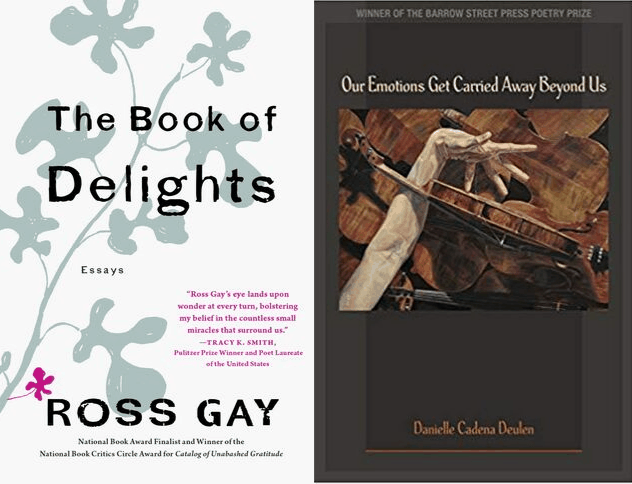

I just finished Our Emotions Get Carried Away Beyond Us by Danielle Cadena Deulen, and it is just incredible—floored me, every poem. We had the fortune of meeting during my recent visit to her campus; I opened her book on my flight to the next visit and couldn’t put it down. Next I plan on finishing Ross Gay’s new one, The Book of Delights.

6. What is the most daring thing you’ve ever put into words? Have you ever written something you wish you could take back?

Writing about my wife’s experience with the birth of our child felt daring. Because of complications, it was such an intense moment for all three of us, but I felt shaky about the ground I could speak from. At a Cave Canem residency, after graciously listening to me struggling to articulate my trouble, Nikky Finney told me, “The words are yours.” Church. She cast a spell of permission that allowed me to find enough alchemy between risks and reasons to move forward, and I went back to my room and wrote (almost unchanged during revision, a *rare* case for me) the first two sections of “What We Set in Motion” from my first book, Revising the Storm. While I don’t (yet) wish to take parts of that poem back, I find that reading it aloud (especially with my wife and child in the room) invites an intimacy that we’re all three still trying to understand.

7. What advice do you have for young writers?

Reach out. With respect and care, reach out and tell the living writers who move you that you were there with them on the page and moved. So often, because there really isn’t a way to be present with all the places one’s work ends up in the world, a writer can feel left with a surplus of hope that the work does good things (or, at least, avoids harm) wherever it goes. So, truly and deeply, I’ve grown to appreciate and honor whatever affirming lights come my way. Because, who knows?

8. What do you think makes a piece of writing compelling?

I find that I respond to writing that understands or admits or accepts maybe that we carry certain questions that have no good answers for us, that those questions can even drive the discovery process without fooling us into false arrivals. The work of Claudia Rankine comes to mind, especially in Don’t Let Me Be Lonely, as does Chris Abani’s work in Sanctificum, to name only a couple. I was corresponding with the writer Leslie St. John just the other day, and I think we were in agreement—that I’m generally asking the same driving questions that I’ve continued to ask (and suspect will continue asking) of the poems I write/read: Can poetry create more resilience in my life? Is it working? Have I gotten back up yet? I keep hoping and praying so. But, yeah, it seems to me that the real bet I keep making on art is that the elasticity required of reading and writing poems has the potential to sharpen and/or transform the nature of our voices and hands, how they engage other people and ourselves.

“With respect and care, reach out and tell the living writers who move you that you were there with them on the page and moved.”

9. Why do you think people need stories?

Recognition. In my experience, our loneliness evolves—even in the absence of major triggering life events, like falling out of love or losing someone dear or just making a life mistake. Reading and writing poems give me a fair shot at evolving my sense of connection along with that new loneliness.

10. Can you tell us about one of your most memorable moments experienced within the Cave Canem community?

I was in the 2012 room that Terrance Hayes so impossibly and beautifully described in his speech at 2016 National Book Awards, honoring Cave Canem, Toi Derricote, and Cornelius Eady. (You can still find it online I believe.) It was my first of three back-to-back residencies, and I have never been the same since. Something happened in that room, during that year, and differently profound things happened the other two years. Another poet, Rose Smith, cleared me from the room on a different occasion. Like those early childhood moments of encountering stories that had me reaching for my sides to get traction on some resonating recognition being offered, my experience at CC converted me into a reader/listener willing to find and receive a voice that requires me to rock my body, literally, around a new hearing.

Geffrey Davis is the author of two full collections of poetry: Night Angler (BOA Editions, 2019), winner of the 2018 James Laughlin Award and Revising the Storm (BOA Editions, 2014), winner of the A. Poulin Jr. Poetry Prize and a Hurston/Wright Legacy Award finalist. He is also the author of the chapbook Begotten (URB Books, 2016), coauthored with F. Douglas Brown. His poems have been published or are forthcoming in Crazyhorse, Mississippi Review, New England Review, New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, PBS NewsHour, Ploughshares and elsewhere. A native of the Pacific Northwest, Davis teaches for the University of Arkansas’s MFA in Creative Writing & Translation and for The Rainier Writing Workshop low-residency MFA program. Join Geffrey Davis for a new works reading alongside Camonghne Felix and Ladan Osman on October 17, 2019, 6:30pm at The New School.