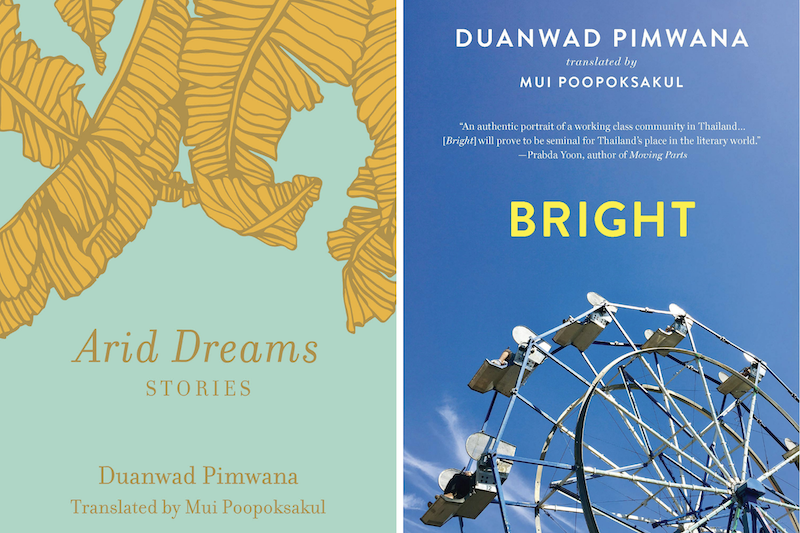

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, in celebration of Women in Translation month, PEN America’s Public Programs Manager Lily Philpott speaks with Duanwad Pimwana, author of Arid Dreams (Feminist Press, 2019) and Bright (Two Lines Press, 2019). Translated from the Thai by Mui Poopoksakul.

1. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

[Question in Thai: กระบวนการสร้างสรรค์ของคุณเป็นอย่างไร คุณมีวิธีรักษาระดับแรงขับเคลื่อนและแรงบันดาลใจอย่างไร]

เดือนวาด : ฉันเป็นคนคิดมากและคิดละเอียด ก่อนจะลงมือเขียนงานสักชิ้นจึงหมดเวลาไปไม่น้อยกับการครุ่นคิดใคร่ครวญ เมื่อคิดจนเกิดภาพค่อนข้างชัดเจนแล้วจึงลงมือเขียน อย่างไรก็ตาม ขณะเขียนไปตามพล็อตที่วางไว้ฉันยังคงไม่ได้หยุดคิด ดังนั้นในหลายครั้งฉันก็เปลี่ยนพล็อตกลางคัน หรือต่อยอดเรื่องราวให้ละเอียดขึ้น, มากขึ้นได้ตลอดเวลา ฉันไม่ได้มีแบบแผนหรือกฏเกณฑ์ตายตัวในการทำงาน ส่วนใหญ่เขียนไปตามแรงเร้าและความสนใจของตัวเองเป็นที่ตั้ง ผู้คน, เรื่องราว, สถานการณ์ หรือประเด็นต่างๆ ที่เร้าให้ฉันอยากเขียนนั้น ต้องสร้างความประหลาดใจให้แก่ฉันก่อนเป็นเบื้องต้น ความประหลาดใจนี้เป็นไปได้หลายแนวทาง อาจเป็นความปลื้มปีติ, อาจเป็นข้อสงสัยจนเกิดคำถาม, อาจเป็นความเศร้าสลดหดหู่ หรือเป็นเรื่องราวที่ไม่เคยพบเห็นมาก่อน เพราะหากเกิดความรู้สึกเหล่านี้ขึ้นกับฉัน ฉันก็แน่ใจว่า ผู้อ่านจะมีความรู้สึกแบบเดียวกันต่องานของฉัน ไม่มากก็น้อย

ส่วนในเรื่องของแรงบันดาลใจ เนื่องจากในช่วงหลังประมาณสิบปีมานี้ สภาพเลวร้ายทางการเมืองในประเทศส่งผลต่อความคิดจิตใจของฉันอย่างมาก แม้ฉันจะยังคงสร้างผลงานอยู่อย่างต่อเนื่อง แต่แรงบันดาลใจก็เหือดแห้งไปมาก สิ่งที่ฉันใช้เพื่อผลักดันตัวเองจึงไม่ใช่แรงบันดาลใจแบบเดิมๆ แต่กลายเป็นความสิ้นหวังที่ครอบงำความรู้สึกมาตลอดสิบปีนี้เอง ที่คอยผลักดันให้ทำงานได้ต่อไปเรื่อยๆ ผลงานที่ออกมาในระยะหลังจึงล้วนเป็นการวิพากษ์ทางการเมืองทั้งสิ้น

I’m the type of person who does a lot of thinking, and in detail. Before I embark on a piece of writing, I’ve already spent a lot of time reflecting and ruminating. I don’t start writing until a fairly clear picture has already emerged. Nevertheless, as I’m writing according to the plot I’ve planned out, the thinking doesn’t stop. So I often end up changing the plot in the process, or at any point I might add to the story to make it more detailed, more complex. I don’t have any fixed steps or rules in how I work. The people, stories, situations, or issues that trigger me to want to write about them have to surprise me first and foremost. The surprise could go in different directions—it could be delight, it could be puzzlement that leads to curiosity, it could be sorrow, or something I’ve never encountered before. Because if they give me those feelings, I believe my work would engender the same feelings in my readers, at least to some degree.

As for inspiration, over the past 10 years or so, the atrocious political situation in my country has greatly weighed on my mind. Even though I still create work continuously, my inspiration has dried up to a large extent. My momentum now comes not from the kind of inspiration I used to have, but it’s the hopelessness that’s taken a hold of me for 10 years that’s propelling me to keep working. My recent works have, therefore, been political.

2. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

[Question in Thai: หนังสือเล่มแรก หรืองานเขียนชิ้นแรก ที่ส่งผลต่อคุณอย่างลึกซึ้ง คือเรื่องอะไร]

เดือนวาด : “สู่เสรี” โดย กฤษณะมูรติ แปลโดย สุวรรณา หลั่งน้ำสังข์

Freedom from the Known by Jiddu Krishnamurti, translated by Suvarna Langnamsang.

“When you look around yourself, you should always wonder whether there’s something extraordinary hidden, then use your imagination to search for it.”

3. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

[Question in Thai: งานเขียนของคุณค้นหาเส้นทางจากความจริงอย่างไร อะไรคือความสัมพันธ์ระหว่างความจริงกับเรื่องแต่ง]

เดือนวาด : นักเขียนแต่ละคนมีวิธีค้นหาต้นทุนงานเขียนแตกต่างกันไป ประสบการณ์ส่วนตัวของแต่ละคนอาจถือเป็นต้นทุนหลัก ฉันเองก็เป็นนักเขียนที่ใช้ประโยชน์จากประสบการณ์ของตัวเองอย่างเต็มที่ แต่ถึงที่สุดแล้วก็มีสิ่งที่สำคัญกว่าประสบการณ์ จะทำให้โลกแห่งความเป็นจริงรอบตัวกลายเป็นวัตถุดิบอันมีค่าในโลกวรรณกรรม จำเป็นต้องอาศัยสายตาและความคิดที่ใส่ใจและกระตือรือร้นเป็นพิเศษ ฉันเชื่อว่าคนเป็นนักเขียนควรมีสายตาและความคิดเช่นนี้เป็นพื้นฐาน เป็นสายตาและความคิดที่สามารถสร้างความหมายเฉพาะขึ้นมาได้จากสิ่งที่ดูไร้ความหมาย แน่นอนเรื่องเช่นนี้คงไม่ง่าย เมื่อคุณมองสิ่งต่างๆรอบตัว ควรนึกสงสัยไว้เสมอว่าอาจมีเรื่องราวไม่ธรรมดาซุกซ่อนอยู่ จากนั้นใช้ความคิดและจินตนาการของคุณค้นหาความไม่ธรรมดานั้น คุณอาจต้องทุ่มเทความใส่ใจและใช้เวลาสักนิด เพื่อให้เรื่องราวพิเศษงอกเงยขึ้นมาจากเรื่องธรรมดาสามัญนั้นให้ได้

โลกแห่งความจริงนั้นซับซ้อน พร่าเบลอ และดิบเถื่อน มีกระแสเรียกร้อง ผลักดัน และชวนเชื่ออยู่ตลอดเวลา แต่ก็เป็นแหล่งต้นทุนของโลกวรรณกรรม ส่วนโลกวรรณกรรมแม้เป็นเพียงโลกเสมือน แต่เป็นโลกที่ชี้ชัดและแสดงปรากฏการณ์ที่เต็มไปด้วยความหมายสำหรับมนุษย์ หากคุณไม่เคยฉุกคิดหรือตั้งข้อสงสัยใดๆ ในชีวิต เพราะโลกแห่งความจริงมักชวนเชื่อให้คล้อยตาม วรรณกรรมจะชวนให้คุณหัดสงสัยหรือประหลาดใจกับบางสิ่ง หรือหากคุณไม่เคยปลื้มปีติต่อความงามของชีวิต เพราะมีหัวใจที่ชาชินเสียแล้ว วรรณกรรมจะทำให้คุณรู้สึกรู้สากับความงามนั้นอีกครั้ง หรือหากโลกแห่งความจริงทำให้คุณเคยชินกับการอยู่ร่วมกับสิ่งเลวร้ายอัปลักษณ์ โลกของวรรณกรรมจะทำให้คุณทนไม่ได้, ไม่สามารถกระทำหรืออยู่ร่วมกับสิ่งเลวร้ายได้อีกต่อไป ฉันหวังเสมอ ว่าวรรณกรรมจะส่งผลย้อนคืนสู่โลกแห่งความจริงได้ ไม่มากก็น้อย

Each writer has their own way of finding raw material for their work. For each, personal experiences might be the primary source of it—I myself am a writer that takes full advantage of them. But ultimately there’s something more important: To be able to transform the world around you into valuable ingredients for literature, you need an especially active and attentive eye and mind. I think these are fundamental to being a writer. They are what will distill specific meaning out of something that seems meaningless. Of course, it isn’t so easy. When you look around yourself, you should always wonder whether there’s something extraordinary hidden, then use your imagination to search for it. It might require a bit of time and attention on your part to make the extraordinary spring up from something common.

The real world is complex, blurry, and crude—it’s full of forces calling, pushing, and prompting—but it’s the raw material of literature. The world of literature might only be an imitated world, but it’s one of clarity and meaningful depictions of human phenomena. If you’ve never stopped to question things because the real world has a way of persuading you to go along, literature will encourage you to practice questioning and being surprised. Or if you’ve never rejoiced in the beauty of life because your heart has been made numb, literature will make you sensate to that beauty again. Or if the world of reality has conditioned you to living among hideous and horrible things, literature will make you unable to tolerate them, unable to take part in or live among them any longer. I always hope that, to some degree, literature’s effect will find its way back into the world.

4. How can writers affect resistance movements?

[Question in Thai: นักเขียนสามารถส่งผลต่อขบวนการเคลื่อนไหวต่อต้านได้อย่างไร]

เดือนวาด : ด้วยสถานะของนักเขียน ซึ่งมีอาชีพและหน้าที่แปรความคิดเป็นตัวหนังสืออยู่แล้ว ฉะนั้นจึงทำได้ทันทีหากคิดจะทำ ปัญหาจึงอยู่ที่ตัวนักเขียนเองต้องการมีส่วนร่วมกับขบวนการเคลื่อนไหวต่อต้านต่างๆหรือไม่ การเคลื่อนไหวเรียกร้องใดๆ ในโลกนี้ สุดท้ายก็อยู่บนหลักการพื้นฐานเดียวกันคือเรื่องของสิทธิมนุษยชน และวรรณกรรมก็ทำหน้าที่เป็นส่วนหนึ่งของหลักการนี้เช่นเดียวกัน นักเขียนบางคนอาจตระหนักถึงเรื่องนี้แบบเข้มข้น และใช้วิธีการนำเสนอที่ตรงไปตรงมาด้วยสถานะของนักสิทธิมนุษยชนเต็มตัว แต่นั่นหมายถึง เราอาจกำลังสูญเสียนักเขียนวรรณกรรมสร้างสรรค์คนหนึ่งไป แล้วได้นักต่อสู้ด้านสิทธิมนุษยชนมาแทน ซึ่งฉันคิดว่า พื้นที่และสถานะของการแสดงออกเป็นเรื่องสำคัญเช่นกัน นักสิทธิมนุษยชนอยู่ในพื้นที่หนึ่ง วรรณกรรมสร้างสรรค์ก็อยู่ในพื้นที่หนึ่ง ถูกเสพรับโดยกลุ่มบุคคลต่างๆ กันไป ฉันเป็นนักเขียนวรรณกรรม เลือกแสดงออกผ่านวรรณกรรม เพื่อให้วรรณกรรมเป็นอีกพื้นที่หนึ่งที่ปรากฏการเคลื่อนไหวต่อต้านเรื่องราวที่ขัดกับหลักสิทธิมนุษยชน

ซึ่งอันที่จริงไม่ใช่เรื่องจำเพาะว่าพื้นที่ใดบ้างสามารถส่งผลต่อขบวนการเคลื่อนไหวต่อต้าน เพราะมนุษย์ทุกคนควรมีพื้นฐานความคิดต่อต้านการกดขี่อยู่ในตัว และไม่ว่าคุณยืนอยู่ตรงไหน อาชีพอะไร ก็ควรแสดงมันออกมาในทุกครั้งที่พบเจอเรื่องเหล่านี้

Writers, it being their profession and duty to transform thoughts into words, can do that immediately if they choose to. The question is whether the writer him- or herself wants to participate in resistance movements or not. The various movements around the world ultimately stand on the same principle, which is human rights, and literature, too, serves this same principle. Some writers are acutely attuned to this point and take a very direct approach in their writing, fully embracing the status of human rights activists. But that could mean we are trading a literary writer for a human rights fighter. In that regard, I think the forum and status of the expression carry some import. Human rights activists operate in one forum, while writers of literature another. Their work is consumed by different groups of people. I am a writer of literature. I choose to express myself through literature and make it another forum where movements resisting matters counter to human rights will appear.

But actually, the ability to influence resistance movements isn’t limited to certain arenas. Every human being should have within them baseline values that make them want to challenge oppression. And no matter where you’re standing, or what your profession is, you should express these values every time you encounter such matters.

5. Tell us about your favorite bookstore, or library.

[Question in Thai: โปรดเล่าถึงร้านหนังสือหรือห้องสมุดที่คุณโปรดปรานที่สุด]

เดือนวาด : ฉันมีห้องสมุดในใจอยู่แห่งหนึ่งมาเนิ่นนานแล้ว เป็นห้องสมุดท้องถิ่นในจังหวัดชลบุรีบ้านเกิดของฉัน ไม่ใช่เพราะเป็นห้องสมุดที่สวยงาม, ใหญ่โต, มีบริการดี หรือมีหนังสือจำนวนมากแต่อย่างใด แต่เป็นเพราะช่วงเวลาหนึ่งเมื่อครั้งที่ฉันเริ่มเขียนหนังสือได้ไม่นาน ที่บ้านของฉันไม่มีสภาพที่เหมาะสมสำหรับจะนั่งเขียนหนังสือได้ ห้องสมุดแห่งนั้นจึงกลายเป็นห้องทำงานของฉันอย่างถาวรในช่วงเวลาหนึ่ง งานเขียนที่ผลิตออกมาในระยะสิบปีแรกถูกเขียนขึ้นที่ห้องสมุดแห่งนี้เป็นส่วนใหญ่ ฉันไม่เคยลืม โต๊ะ เก้าอี้ และห้องต่างๆ ที่เคยใช้นั่งเขียนหนังสืออยู่เป็นเวลานาน สถานที่นี้จึงยังอยู่ในใจฉันเสมอ

I’ve long had one library in my heart. It’s a local library in Chonburi, my home province. It’s not that it’s a beautiful or grand library with great service or a large selection of books at all. But it’s that there was a period of time, when I’d just started writing and didn’t have a proper setup at home for it, that that library served as my permanent office. Most of my writing from the first 10 years was produced in that library. I’ve never forgotten the various desks, chairs, and rooms where, for a long time, I used to sit and write, so this place has always been in my heart.

6. What do you consider to be the biggest threat to free expression today? Have there been times when your right to free expression has been challenged?

[Question in Thai: คุณมองว่าอะไรคือภัยคุกคามเสรีภาพในการแสดงออกมากที่สุดในทุกวันนี้ เคยมีช่วงเวลาที่เสรีภาพในการแสดงออกของคุณโดนท้าทายหรือไม่]

เดือนวาด : หลายปีมานี้ประเทศของฉันอยู่ภายใต้การปกครองของคณะรัฐประหาร อยู่ภายใต้รัฐธรรมนูญของคณะรัฐประหาร จึงไม่ใช่เพียงฉันเท่านั้น แต่ประชาชนทั้งประเทศต้องตกอยู่ภายใต้การถูกคุกคามสิทธิเสรีภาพตลอดเวลา และแม้ขณะนี้เราผ่านการเลือกตั้งแล้ว แต่ดูเหมือนไร้ประโยชน์และประชาชนยังไม่อาจสัมผัสได้ถึงความเป็นประชาธิปไตยแม้แต่น้อย เรายังคงต้องอยู่ภายใต้รัฐธรรมนูญของคณะรัฐประหารและยังคงถูกคุกคามสิทธิและเสรีภาพอยู่เช่นเดิม

แต่ถึงอย่างนั้น ภัยคุกคามเสรีภาพในการแสดงออกที่เป็นปัญหามากที่สุดสำหรับฉันไม่ใช่สภาพการณ์เบื้องต้นที่กล่าวมา และไม่ใช่การคุกคามต่อตัวฉันโดยตรง แต่คือการที่ประชาชนส่วนหนึ่งยินดีที่จะคุกคามสิทธิและเสรีภาพของตนเอง ยินดีให้เกิดการรัฐประหารประเทศ กระทั่งยินดีใช้ตัวเองเป็นฐานสนับสนุนเผด็จการ สำหรับฉัน ถ้าคุณเป็นผู้หนึ่งที่สนับสนุนการรัฐประหาร ตัวคุณนั่นแหละคือภัยคุกคามเสรีภาพที่เป็นปัญหาและน่ารังเกียจที่สุด

Over the past several years, my country has been under military rule, under the law of the junta’s constitution. So it’s not only my freedom of expression, but also that of everyone in the whole country, that’s under constant threat. Even though we’ve now held an election, it appears to have been useless, and democracy remains elusive to the people. We continue to have to live under the junta’s constitution and to have our rights and freedoms threatened.

Even so, to me, the biggest threat to freedom of expression isn’t the situation I just described, and it isn’t any threat directed at me personally. But it’s the fact that a portion of the population is willing to infringe their own rights and freedoms, willing to allow a coup d’état to happen, and even willing to submit themselves as members of the dictatorship’s support base. To me, if you’re a supporter of the coup, you are the biggest, most revolting threat to freedom.

7. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity”?

[Question in Thai: อัตลักษณ์ในตัวคุณส่งผลต่องานเขียนของคุณอย่างไร คุณคิดว่า “อัตลักษณ์ของนักเขียน” มีอยู่จริงหรือไม่]

เดือนวาด : หากอัตลักษณ์ของมนุษย์ผู้หนึ่งหมายถึงตัวตน ลักษณะนิสัย และสถานภาพของเขา ฉันคงต้องบอกกับผู้อ่านว่า คุณอาจไม่ได้เห็นตัวตนของฉันอยู่ในงานเขียนของฉันเลย ฉันอาจเขียนถึงประสบการณ์ใกล้ตัวจากครอบครัวของตัวเอง อาจเคยสร้างตัวละครจากต้นแบบที่เป็นคนใกล้ชิด หรือคนที่ฉันเคยปฏิสัมพันธ์ด้วย แต่ทว่า ฉันกลับมีความตั้งใจอยู่เสมอมาที่จะไม่เขียนถึงตัวเอง ไม่ใช้ตัวเองเป็นต้นแบบ พูดได้ว่าในฐานะผู้เขียนฉันมีระยะห่างกับเรื่องเล่าของตนเองเสมอ แน่นอนว่าผู้อ่านจะเห็นความคิดของฉันอยู่ในประเด็นหรือนัยยะของงานทุกชิ้น จากความคิดเหล่านั้นจะสามารถตีความหรือมองหาอัตลักษณ์ตัวตนของฉันได้มากน้อยเพียงใดก็แล้วแต่ผู้อ่าน แต่นี่คือนิสัยอย่างหนึ่งของฉัน คือไม่นิยมเขียนถึงตัวเอง สายตาของฉันเพียงทำหน้าที่ของนักสังเกตการณ์ต่อเรื่องราวและชีวิตที่ได้ผ่านพบ แล้วถ่ายทอดออกมาด้วยวิธีคิดและมุมมองแบบเดือนวาด

ฉันไม่ทราบว่า “อัตลักษณ์ของนักเขียน” มีอยู่จริงหรือไม่ หรืออัตลักษณ์แบบไหนที่บ่งบอกความเป็นนักเขียน อาจมีคุณลักษณ์บางอย่างของคนเขียนหนังสือที่แตกต่างหรือพิเศษกว่าคนทั่วไป ทว่านักเขียนทุกคนก็มีลักษณะเฉพาะที่บ่งบอกความแตกต่างอยู่ดี ตัวฉันแทบไม่เคยคิดหรือเห็นความสำคัญว่าจะมีอัตลักษณ์ของตัวเองอยู่ในงานเขียนหรือไม่ เพียงคิดว่า งานเขียนของเดือนวาด ย่อมแสดงอัตลักษณ์ทางความคิดของเดือนวาด นั่นคือข้อเท็จจริงอย่างไม่ต้องสงสัย

If a person’s identity means their being, their characteristics, and their various statuses, I’d have to say to my readers, you may not see me in my work at all. I may write about experiences familiar to me because of my background, may have created characters based on someone close to me or someone I’m acquainted with, but my intention has always been not to write about myself, not to use myself as a template. One could say, as a writer, I’ve always maintained a distance between my self and my work. Of course, my thoughts are perceptible in the issues and meanings embedded in every piece of my work. From those thoughts, how much or how little of my identity can be gleaned, that’s up to the readers to interpret. But that’s one aspect of my temperament: I prefer not to write about myself. My eyes merely function as the observers of the events and life that I encounter, which I then render through my perspective and way of thinking.

I don’t know if there’s such a thing as “the writer’s identity,” or what kind of identity conveys a writer. People who write might have certain characteristics that are different from or beyond what other people have. But each writer has their own individuality anyway. I myself almost never consider or place importance on whether or not my identity appears in my writing. I simply think, my writing would naturally reveal the contours of my thoughts. That’s true without question.

8. What advice do you have for young writers?

[Question in Thai: คุณมีข้อแนะนำใดสำหรับนักเขียนรุ่นน้องหรือไม่]

เดือนวาด : ฉันเคยเป็นนักเขียนใหม่มาก่อน ตอนนั้นฝีมือยังอ่อน ความคิดและทัศนคติยังเด็ก แต่สิ่งซึ่งเป็นจุดแข็งที่น่าริษยาคือ นักเขียนใหม่ทุกคนมักมีไฟเต็มเปี่ยม มีความฝันและมีแรงบันดาลใจที่สดใหม่ ซึ่งฉันรู้ในเวลาต่อมาว่ามันมีค่ามาก ความตื่นตัวของวัยหนุ่มสาวเป็นพลังมหาศาล และหากว่าคุณยังมีอิสระเสรี ปลอดพ้นจากพันธะหรือภาระใดๆ จงรู้ไว้เถิดว่านี่คือช่วงวัยและเวลาที่ดีที่สุดที่จะทุ่มเทให้แก่การเขียนหนังสือ เพราะเมื่อเวลาผ่านไป พันธะและภาระของชีวิตจะเพิ่มขึ้นตามวัย ดวงไฟในตัวคุณจะถูกบั่นทอนลงทีละน้อยและอาจไม่สามารถย้อนคืนไปสู่จุดเดิมได้อีก ดังนั้น ใช้พลังที่ยังเต็มเปี่ยมในตัวคุณให้คุ้มค่าที่สุดเท่าที่จะเป็นไปได้ เพราะนั่นคือต้นทุนแสนวิเศษของนักเขียนใหม่จริงๆ

I was a new writer once. Back then, I was inexperienced and my thoughts and outlook not yet mature. But new writers have one enviable strength, which is that they all tend to be full of fire. They have dreams and inspirations that are fresh. I came to realize later on that these are extremely valuable. The fervor of youth is an immense force, and if you still have the freedom and are still unbound by ties and obligations, do know that that is the best period of your life to dedicate yourself to writing, because life’s ties and obligations will mount with age. The fire in you will be dimmed bit by bit, and it may never recover fully again. Therefore, make the most of that energy that’s still bountiful in you, because that is truly the magical quality that new writers possess.

“Try taking a look at yourself, at society and life again through the world of literature. Maybe you’ll find a truer reality and see why people need stories.”

9. Why do you think people need stories?

[Question in Thai: คุณคิดว่าทำไมผู้คนถึงต้องการเรื่องเล่า]

เดือนวาด : ก่อนจะเป็นนักเขียน ฉันเคยเป็นเด็กวัยรุ่นที่อ่านหนังสือแบบเล่นๆ เพื่อเป็นความบันเทิงเท่านั้น เหมือนชาวบ้านทั่วไปที่มีชีวิตแบบไม่ได้ก้าวเดินด้วยตนเอง แค่ไหลไปตามกระแสสังคม ผู้คนบนโลกนี้คงมีไม่น้อยที่เคยเป็นเหมือนฉัน อยู่บนโลกแห่งความเป็นจริงแต่แท้แล้วไม่รู้จักชีวิตและไม่เคยเรียนรู้อะไรอย่างแท้จริงเลย ได้แต่ฟังโฆษณาชวนเชื่อและหวาดกลัวว่าตัวเองจะไม่เหมือนคนอื่นๆในสังคม ต่อมาเมื่อได้อ่านวรรณกรรมแบบจริงจัง สายตาและวิธีคิดก็เริ่มเปลี่ยนไป ฉันได้พบโลกและชีวิตในอีกพื้นที่หนึ่ง ตัวของฉันเองก็ปรากฏขึ้นใหม่ในพื้นที่นั้น เป็นตัวฉันที่โง่เขลาไม่เคยฉุกคิดสงสัยในความไม่ชอบมาพากลต่างๆ แม้จะเห็นมันอยู่ตรงหน้าก็ตาม เป็นตัวฉันที่อัปลักษณ์และไร้จุดยืน ขาดวิจารณญาณที่ถูกต้อง ฉันไม่ชอบอยู่ภายใต้อิทธิพลการสั่งสอนของใคร ดังนั้นวรรณกรรมหรือเรื่องเล่า หรือหนังสือแต่ละเล่ม ที่เพียงแต่แสดงเนื้อหาต่อคุณ ไม่มีสิทธิจะรบเร้าหรือบังคับให้คุณเชื่อ จากนั้นปล่อยให้คุณเลือกวิถีชีวิตด้วยวิจารณญาณของคุณเอง วิธีนี้จึงเหมาะกับคนแบบฉันอย่างยิ่ง

มนุษย์สามัญโดยทั่วไปก็เช่นกัน เป็นเรื่องยากที่ทุกคนจะสามารถรู้เท่าทันตัวเองได้เสมอไป เพราะแท้แล้วโลกและชีวิตไม่ได้บอกความจริงแก่คุณ ลองมองตัวคุณเอง มองสังคมและชีวิตอีกครั้งผ่านโลกวรรณกรรม บางทีคุณจะพบความจริงที่จริงกว่า และเห็นคำตอบว่า ทำไมผู้คนถึงต้องการเรื่องเล่า

Before I became a writer, I was a kid reading for fun, just for the entertainment value. I was no different from people out there who move through life not walking on their own but swept along by the tides of society. Probably a lot of people are that way—living in the world of reality and yet not really knowing life or learning anything truly, just listening to advertisements and worrying that they wouldn’t be like other people. Later on, after I started reading literature seriously, my perception and way of thinking began to change. I re-met the world, and life, in another space. My own self also reappeared there. That self was ignorant and unquestioning, even when something suspicious was right in front of it. It was a hideous self, one without judgement or a stance of its own. Now, I like to make up my own mind, so the way that literature, or stories, or books reveal their substance to you—but can’t beseech or force you to believe them—and then let you use your own judgment to choose your way of life, suits someone like me very well.

In general, it’s difficult for people to be aware of their own behavior, because the world and life don’t lay the truth out for you. Try taking a look at yourself, at society and life again through the world of literature. Maybe you’ll find a truer reality and see why people need stories.

10. Two of your books were published in English this year (Arid Dreams with Feminist Press, and Bright with Two Lines Press) and are regarded as the first major English-language publications of work by a Thai woman writer. What is your relationship to the English translation of your work? How do you think English-speaking audiences will receive your work?

[Question in Thai: หนังสือสองเล่มของคุณได้รับการตีพิมพ์เป็นภาษาอังกฤษในปีนี้ (Arid Dreams กับ Feminist Press และ Bright กับ Two Lines Press) และได้รับการยกย่องว่าเป็นการตีพิมพ์ในภาษาอังกฤษครั้งสำคัญของนักเขียนสตรีไทย คุณมีความสัมพันธ์อย่างไรบ้างกับผลงานฉบับภาษาอังกฤษของคุณ คุณคิดว่านักอ่านในภาคภาษาอังกฤษจะต้อนรับผลงานของคุณเช่นไร]

เดือนวาด : ผลงานแปลทั้งสองเล่มมาจากงานที่เขียนไว้นานพอสมควร หลายเรื่องฉันลืมเนื้อหาไปแล้ว เมื่อเข้าสู่กระบวนการแปลฉันต้องย้อนกลับไปอ่านผลงานเหล่านั้นอีกครั้งเพื่อสามารถคุยรายละเอียดและทำความเข้าใจกับนักแปลได้ อารมณ์ความรู้สึกตอนนั้นคล้ายกับเมื่อครั้งที่ผลงานจะได้รับการจัดพิมพ์รวมเล่มเป็นครั้งแรกในเมืองไทย ฉันมักนั่งคิดแบบไม่ค่อยเชื่อตัวเองอยู่บ่อยๆ แรกๆ ก็ไม่อยากเชื่อว่าตัวเองจะเป็นนักเขียนได้, ไม่อยากเชื่อว่าจะมีหนังสือของตัวเองวางขายตามร้านหนังสือทั่วประเทศ มาถึงตอนนี้หนังสือได้รับการแปล ได้รับการจัดพิมพ์ทีเดียวสองเล่ม กับสองสำนักพิมพ์พร้อมๆ กันในอเมริกา แน่นอน ความรู้สึกเดิมๆ ย้อนกลับมาอีก ในฐานะลูกสาวของครอบครัวชาวไร่ที่เคยยากจนและมีการศึกษาเพียงน้อยนิด ไม่น่าเชื่อว่าสิ่งนี้จะเกิดขึ้นกับฉัน

ฉันได้รับโอกาสที่ดีมากจริงๆ การเปิดตัวด้วยหนังสือที่จัดพิมพ์พร้อมกันสองเล่ม สองสำนักพิมพ์ คงไม่ใช่เรื่องที่เกิดขึ้นได้ง่ายๆ สำหรับฉันยังมีเรื่องที่น่าตื่นใจมากกว่านั้นอีก เพราะหนังสือทั้งสองเล่มเป็นผลงานที่มีความแตกต่างกันอย่างมาก นี่จึงเป็นความคาดหวังของฉันต่อผู้อ่านภาษาอังกฤษ ซึ่งเพิ่งจะรู้จักชื่อ เดือนวาด พิมวนา เป็นครั้งแรก ฉันอยากให้ผู้อ่านได้เห็นความต่างนี้ ได้สัมผัสและเปรียบเทียบหนังสือทั้งสองเล่มซึ่งแตกต่างห่างไกลแต่เขียนโดยคนเดียวกัน เพราะนี่คือผลผลิตส่วนหนึ่งของวิธีคิดและวิธีสร้างงานของฉัน คือความพยายามที่จะไม่ย่ำอยู่กับที่ ความพยายามที่จะสร้างทัศนียภาพแปลกตาภายใต้ชื่อของนักเขียนคนเดียวกัน ฉันอยากให้พวกคุณเห็นมัน

Both of the books were translated from works that I wrote quite a long time ago. I’d already forgotten a lot of the plots. During the translation process, I had to go back and reread those works so that I could discuss the details with my translator. The feeling then was similar to when the works were getting collected and published as books for the first time in Thailand. I often sat there thinking sort of in disbelief. In the beginning, I couldn’t believe that I could be a writer, couldn’t believe that my books would be sold in bookstores all over the country. And now my books have been translated, two of them published at once, by two different publishers in the United States. Certainly, the same feelings returned. As the daughter of farmers who used to be poor and only has a little bit of education, I can hardly believe that these things would happen to me.

I was given an amazing opportunity—to debut with two books at the same time, from two different publishers, probably is something quite rare. For me, there’s even more that’s thrilling: the two books are drastically different. My hope for English-language readers, who are getting to know the name Duanwad Pimwana for the first time, is, I want them to see the contrast, to experience and compare the two books, which are so vastly different but written by the same person. Because they are the results of my creative approach, my aim not to march in place, my strive to create distinct panoramas under one writer’s name. That’s what I want you to see.

A major voice in contemporary Thai literature, Duanwad Pimwana is known for fusing touches of magical realism with social realism. She won the S.E.A. Write Award in 2003 for her novel Bright (Changsamran), which became one of her English-language debuts this spring, along with her story collection Arid Dreams. Pimwana is the author of nine books, including a novella and multiple collections of short stories, poetry and cross-genre writing. She lives in the Thai east-coast province of Chonburi.

Mui Poopoksakul is a lawyer-turned-translator with a special interest in contemporary Thai literature. She is the translator of Prabda Yoon’s The Sad Part Was and Moving Parts, both from Tilted Axis Press. Her translations of Duanwad Pimwana’s story collection Arid Dreams (Feminist Press) and novel Bright (Two Lines Press) were published in April 2019. A native of Bangkok who spent two decades in the U.S., she now lives in Berlin, Germany.