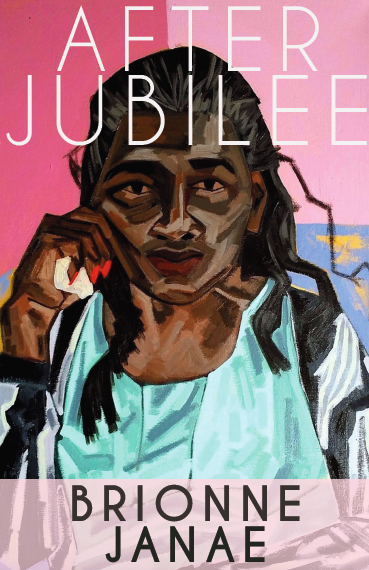

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Cave Canem Foundation’s Programs and Communications Fellow Desrosiers speaks to Brionne Janae, a poet and teaching artist living in Brooklyn whose debut collection, After Jubilee, was published by BOAAT Press in 2017. Join Brionne Janae for a new works reading alongside Nabila Lovelace and Justin Phillip Reed on February 22, 2019, at NYU.

1. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity”?

I believe our identities give context to our experience, and as result I know that my identity gives context for my work. In a master class I attended in grad school, I remember Claudia Rankine saying of Citizen that she wasn’t protesting anything when she wrote the book, but that she was simply writing from her existence. I was so struck by that, because it relieved me from the pressure/restriction of feeling like I was or needed to be a black writer writing about black subjects or a queer writer writing about queer topics. No, I was just writing from the space in which I exist in the world, and where I exist is Black and queer and woman, and so that reality naturally informs my work.

In terms of the “writer’s identity,” I don’t think there can be any sort of fixed expression of this, but I do think there are some traits and habits I have that have lent themselves to that identity. For example, I’ve always had a bad habit of staring or watching people, especially when I was a kid. A lot of the times I wouldn’t even notice I was doing it, until someone pointed it out. As an adult though I’ve realized that this looking is driven by an intense curiosity about what people are doing, why they’re doing it, what they feel in those moments, and all the little histories that have lead them to this feeling and action are a part of what led me to writing, and poetry. In short I suppose empathy, or the desire to share feelings with those around you is probably the most essential part of the “writer identity,” for me at least.

2. In an era of “alternative facts” and “fake news,” how does your writing navigate truth? And what is the relationship between truth and fiction?

Honestly, I’ve always found the idea of “alternative facts” very interesting, and in some ways deeply empowering. I remember first hearing the term and thinking, of course the Trump Administration wants to use alternative facts to cover up all of their foolishness. First of all, it is a deeply human phenomenon. Who hasn’t tried to embellish or change their reality to avoid facing the unflinching truth. The problem is that those in power, or those blinded by privilege are the ones who get to live in this alternative reality land where their actions have no consequences, (or at least none for them) and the rest of us are stuck struggling under the weight of their fantasy.

“It is not permissible,” James Baldwin writes in his letter to his nephew on the 100th anniversary of emancipation, “that the authors of devastation should also be innocent. It is the innocence which constitutes the crime.” This narrative of American innocence is so pervasive in our culture that it only makes sense that “alternative facts” should appear as a part of the natural progression, or evolution of the great American delusion. But as I said, I find the idea of “alternative facts” empowering. Not in the way they have been used by those in power, but for how they might be used as a means to subvert and transcend the realities of the systemically unlucky. And so, about a year ago, I wrote two poems entitled “Alternative Facts” that reimagined the killings of Trayvon Martin and Tamir Rice. It was my hope that in fictionalizing their deaths I might critique the reality that they lived and died in. A reality where the officer couldn’t see the 12-year-old boy in Tamir’s face, or where a crazed vigilante would dare to extinguish the god in Trayvon.

3. Writers are often influenced by the words of others, building up from the foundations others have laid. Where is the line between inspiration and appropriation?

I like to think of writing anything as participating in a conversation. So when you are writing a poem that is inspired by, or after another poem or poet, you need to be in conversation with that poet’s work, meaning you need to add something new, and worth saying. A conversation between two people where one merely repeats what the other person has said is not a conversation.

4. “Resistance” is a long-employed term that has come to mean anything from resisting tyranny, to resisting societal norms, to resisting negative urges and bad habits, and so much more. Is there anything you are resisting right now? Is your writing involved in that act of resistance?

Honestly, the only thing I’m resisting right now is despair. One of the difficulties of living in our current time is the easy access we have to the news, and that the news is particularly devastating. Like a lot of my friends, I find it hard to spend the day scrolling through my timelines and finding out about the latest tragedy, killing, scandal, but also it feels irresponsible to look away. If I’m not careful I can get so absorbed into the calamity of the news that I find it almost impossible to write (or do anything really), like I’ve been silenced by the despair of it all. Or when I do write all I can write about is the devastation in the world.

So my act of resistance is to first and foremost curate and protect joy in my life, and second to remember to write, and remember to write about more than just calamity. As a part of that resistance, for the past year or so I’ve been working on a novel, which feels scary-strange and fun all at once. The whole project of the novel is me imagining a world where black people have left earth and created a new world for themselves on another planet. I don’t know if or when I’ll ever finish it, but I know working on it gives me hope and joy, and that in and of itself feels like victory.

5. Tell us about one of your most memorable moments experienced within the Cave Canem community?

This question feels unfair because there are literally so many memorable moments. There’s just so much love in that community, it feels at once deeply sacred and almost unreal like magic. This summer I graduated from Cave Canem, and during the graduation ceremony Chris Abani stood up and sang a blessing for us in Igbo with English translation, and it was so powerful, because it reminded me that poetry is a deeply spiritual practice. At the beginning he told us that he would bless us and then spray us with the gin as a part of the ritual. And I remember thinking, what do you mean spray? He better not be about to spit that gin on us. But by then end though, when he was indeed walking around the room spraying the gin from his mouth, I was thinking, I hope he doesn’t forget to come to my corner, because I had felt the power of his words and the blessing and I wanted its covering. Even when they kill you in the streets, he said, you will dance on their heads.

“So my act of resistance is to first and foremost curate and protect joy in my life . . . “

6. What’s the most daring thing you’ve ever put into words?

The most daring thing I’ve ever written is probably a poem called “Gut Bucket Blues,” from my book After Jubilee. It’s a blues poem written from the persona of a Black lesbian woman from the South in 1910, who is singing a blues about a lover of hers that’s run off. I wrote this poem after hearing the song “B.D. Woman Blues,” performed circa 1935 by Lucille Bogan and realizing, for what was unfortunately the first time, that there have always been queer black women, and that some of these women were not only queer but out and proud of it. “Comin’ a time, B.D. women ain’t gonna need no men,” I just remember hearing those words, and then rushing to look up B.D. woman which was short for bull dyke or bull dagger women, and discovering the history and just imagining a group of queer black ancestors living their best lives in open defiance of all the constraints the world would have tried to place on them. The reaction I had to this knowledge was quite visceral. My whole body was buzzing as if I was regaining something I had lost or stepping into myself. For context, at the time I didn’t “know” I was queer, or more accurately perhaps, I was in deep deep deep denial of my queerness. And yet there was some part of me that heard that song and couldn’t help but answer the call and so I wrote “Gut Bucket Blues,”

“I hear the juke joints in chicago

got women jiving all night long

they say the blues men in chicago

got colored girls rocking all night long

you always been an easy rider babe,

sure you up their fucking through the dawn

we used to roll biscuits in the morning,

eat jelly rolls at noon nice and slow

we rolled biscuits in the morning,

damned if you didn’t stroke your jelly nice and slow

now you cooking in some back door woman’s kitchen,

with your apron slung down low”

This poem was, by no means daring or revolutionary when it was written, except that for me it actually kind of was. It took me about four years after writing it to dare to come out to myself, and nearly another year to come out to my family. So nowadays whenever I read this poem I can’t help but hear some part of myself, some queer black ancestor daring, demanding even, that I come out and own who I am unabashedly and without reservation.

7. Have you ever written something you wish you could take back? What was your course of action?

Not really. There have been some things that I’ve written and thought, hmmm, maybe I should think about this before I publish it. Or how would publishing this affect my relationship with someone in my life. These moments are always difficult for me, because it can be hard to decide when I should bury a poem for the sake of a relationship, and when I should push ahead and publish the poem. One thing I have found though, is that in the moments when I publish something risky, and it forces tough conversations with people in my life, we at the end of everything have usually been better for the conversation. Hopefully, this continues to be my experience.

8. Post, stalk, or shun: What is your relationship to social media as a writer?

I have a love hate relationship with social media. I wish it didn’t feel so necessary as a platform to promote your work, but also I love that my timelines are full of poets promoting their work and the work of poets they admire: meaning I love that my timeline is always full of good poetry. My personal usage of social media is a bit erratic. I spend most of my time just scrolling and stalking, liking random memes, reading the articles and sharing the ones I like, cooing at the myriad baby photos. Then occasionally I’ll get a surge of confidence and start posting for a bit, then back to the silent stalking.

9. When I think of how your poetry collection, After Jubilee, speaks to—among other things— transcending grief as it’s located in a context of blackness and histories of anti-black violence, I also think of other texts such as Claudia Rankine’s Don’t Let Me Be Lonely and Kevin Young’s Book of Hours, which explore similar topics. In what ways is After Jubilee in conversation with these or other black poets on the subject?

This past month I’ve been reading James Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues” with my college writing students, and one of the things we’ve discussed was the power of blues music to, as Houston A. Baker writes, speak to the “always already,” of African American experience and culture. Meaning, essentially, that the blues is the best medium to communicate the ways that what has already happened to Black Americans is still always happening to Black Americans. I believe the same can be said of poetry.

When I was writing After Jubilee I hadn’t yet read either Rankine or Young’s books, but I had owned Nikki Giovanni’s Collected Poetry since I was 14 and read it often over the years, and can remember all of the grief and rage of her early poems, as she elegized so many fallen black leaders. I had also read an awful lot of Natasha Trethewey, and what I loved about her work was its ability to bring the past flush up against the flesh of the present. And so between reading Giovanni, and books like Thrall, or Native Guard, I began to carry both this idea of “always already,” and too this idea that Claudia Rankine names in an essay for the Times that, “the condition of Black life is one of mourning.”

As a result of all of this swirling around in my conscious and subconscious I remember realizing that there was no difference between the cries of a mother whose child had been lynched by an angry mob or the Klan and the cries of a mother whose child has been shot down in the streets by police, and that those cries are not all that dissimilar from the cries of a mother who loses a child to accidental tragedy. Their grief is one and the same, and the conditions that allowed for their grief are still damningly similar, and the timelessness of this grief, I think, is a part of what brought about the poems that make up After Jubilee.

10. If you could require the current administration to read any book, what would it be?

Just one? But they need so many, and I’d honestly like to throw a whole library at those fools. But if I had to pick I’d choose Layli Long Soldier’s Whereas, because if that book isn’t one of the most breath snatchingly beautiful things ever created I don’t know what is. I also can’t help but admire the way it holds up a mirror to history, and allows this country to damn itself.

Brionne Janae is a poet and teaching artist living in Brooklyn whose debut collection, After Jubilee, was published by BOAAT Press in 2017. She is the recipient of the 2016 St. Botoloph Emerging Artist award, a Hedgebrook and Vermont Studio Center Alumni, and proud Cave Canem fellow. Her poetry and prose have been published by the Academy of American Poets, American Poetry Review, the Sun Magazine, Los Angelas Review Rattle, Bitch Magazine, The Cincinnati Review, jubilat, Sixth Finch, Plume, Bayou Magazine, The Nashville Review, Waxwing, and Redivider, among others.