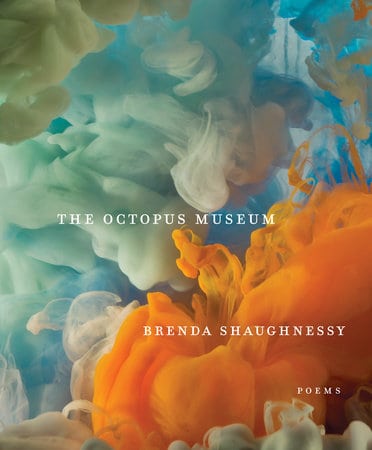

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week PEN America’s Public Programs Manager Lily Philpott speaks with Brenda Shaughnessy, whose latest poetry collection, The Octopus Museum, was published this year by Knopf.

1. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

Truth is bodily, emotional, and it comes out in speech, when I read a draft aloud. I can think my way into any old statement but when I read it out loud and my voice gets tiny and small and I rush through it like no one will notice, I think then that either I haven’t told the truth, or the rhythm’s off. And the good rhythm often stays away from cerebral contortions that don’t yield anything true.

2. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

I have long felt ashamed of the reality that I’ve never been able to maintain a “writing schedule.” I go long periods attending to other aspects of my life, looking longingly over my shoulder at poems and ideas I’d love to get into. Then when I clear away other responsibilities and I have some time and blank pages in front of me, suddenly I’m skittish, fearful of the quiet, silenced by an inner expectation, and just plain bratty and irritated. I don’t maintain momentum until, in a spate of writing, I am seized by it and then it’s not really inspiration but possession. The ideas and phrases and words start to take over other parts of my life, permeating it. It’s no way to live.

3. What is one book or piece of writing you love that readers might not know about?

Cold Skin by Albert Sánchez Piñol. Also, I love Gertrude Stein’s long weird sexy amazing poem “Lifting Belly.

4. How can writers best contribute to society? How can artists affect resistance movements?

When the 2016 presidential elections happened I felt, along with so many others—friends, poets, students—helpless. Verging on hopeless. But poetry is just the thing for teetering on that verge—looking into hopelessness and saying “nope” is what poetry’s all about. Writers can contribute to society by writing, and by not feeling obligated to write about the daily horrors of this regime, or the most recent atrocity or the worst breaking news—but writing what the full range of human emotion and experience and understanding demands. That may include the breaking news, yes! But it also means love poems, poems about trees and seas, still life poems, poems about death and language and the way the world is—all these kinds of poems can pose a radical rethinking of our ways of knowing and communicating. Just like all politics are identity politics, and just like the personal is political—all poems are love poems, all poems are political poems. The act of choosing to write about what matters to a person is a potent form of resistance— that human choice and artistic freedom and full range of ideas and possibilities—all that is very much a part of what the fundamentalist right wing would like to see dead.

“The act of choosing to write about what matters to a person is a potent form of resistance”

5. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

Right now I am immersed in Benjamin Moser’s biography of Susan Sontag. It is extraordinary to see how two writers’ minds work—Moser’s and Sontag’s! Moser has to historically contextualize the life of Susan Sontag as well as deliver personal history, anecdotes from others, archival facts, and her own journals. There are competing narratives. It’s an unbelievably complicated feat but Moser is clear and consistent throughout, all while being full of heart, with great sentences! So as much as I’m learning about this amazing woman, I am simultaneously amazed at just how much Moser is gathering and incorporating and harmonizing.

6. What is the most daring thing you’ve ever put into words? Have you ever written something you wish you could take back?

Every book I’ve written, and there’s now been five of them, have included mistakes. Some little typos, some imprecise word choices, some gaffes. My long title poem in Our Andromeda was the most painful thing I’ve ever written, and the poem “Are Women People?” in The Octopus Museum makes me nauseated—I can’t really even read it or look at it. But I would never take those back—writing those pieces gave me something back that I had been missing/needing: an acknowledgment of how things were/are. Wanting to take back any writing like that would mean wanting to go back into denial, as opposed to wishing I’d said it differently. That last thing is common for me. I’m always realizing I could have said something better, with more nuance, more precision, etc. But that’s not the same as wishing to unwrite pain.

7. Which writers working today are you most excited by?

I am utterly blown away by the depth and wisdom and fire of Franny Choi’s book Soft Science. It’s genius—it goes so far into thinking and feeling that one’s neurology, one’s very cells, feel kind of f*cked [sic] with, in a good way. Jericho Brown’s The Tradition is the announcement of a permanent literary voice. I can see this voice and this book echoing for centuries whether or not humans are here to hear it. I am always very excited and changed by the work of francine j. harris, D. A. Powell, Rachel Eliza Griffiths, and the magnificent fiction writer Samantha Hunt.

8. Which writer, living or dead, would you most like to meet? What would you like to discuss?

I wish I could have met Charlotte Brontë and Octavia Butler. If this is just a wish, I’d like the three of us to be in the room together. I’d want to discuss whatever they wanted, but also I’d like to know their thoughts and theories of gender and sexuality. I think we’d talk for days?

9. What do you think makes a piece of writing compelling?

It has to be alive. I don’t know by what sorcery, but the writing must somehow live.

10. When you were writing your most recent collection, The Octopus Museum, what did a typical day of writing look like? Were there typical days? How did you step back from the apocalyptic future you were crafting to your life and family in the present day?

10. When you were writing your most recent collection, The Octopus Museum, what did a typical day of writing look like? Were there typical days? How did you step back from the apocalyptic future you were crafting to your life and family in the present day?

There were no typical days. I started it at The MacDowell Colony, in a space perfectly suited for howling into the crevasse of what may or may not become anything. There my imagination was utterly free. But I couldn’t stay there forever, or even three weeks. There were 17 atypical, mad-rush, hair-tingling days of full-on creative flow. The book, from there, in drips and drops, would then, in the year afterward, swell up again and swallow me. Whenever I could find a couple or a few hours to let it rage and rip, poems came to me and I wrote them down. I finished the book in Italy, at Civitella Ranieri, and in Kailua, Oahu—both places that were so rare and hard to get to and where the land/seascapes took down any resistance I had to full immersion in this book.

Of course I couldn’t be around my family to do this. I had to leave them to their home routine, which, to be fair, is good for them. But I wrote about my kids a lot, even as I was away from them. I can see them more clearly if I’m away—it’s like the joy and the drudgery and the glory and the anguish/fear of raising kids are less clear when I’m in it. The actual effects and meaning and magnitude of childrearing really hits me when I am away from them; and I do miss them so much I come roaring back trying to absorb the days and hours and moments that I missed because I was writing. I’m torn, and it’s an impossible quandary, an argument with time as always. And isn’t that, at heart, what being a writer is, wanting to live two lives?

Brenda Shaughnessy is the author of five poetry collections, including The Octopus Museum (2019, Knopf); So Much Synth (2016, Copper Canyon Press); Our Andromeda (2012), which was a finalist for the Kingsley Tufts Award, The International Griffin Prize, and the PEN Open Book Award. Her work has appeared in Best American Poetry, Harpers, The New York Times, The New Yorker, O Magazine, Paris Review, Poetry Magazine, and elsewhere. Recent collaborative projects include writing a libretto for a Mass commissioned by Trinity Church Wall Street for composer Paola Prestini, and a poem-essay for the exhibition catalog for Toba Khedoori’s solo retrospective show at LACMA. A 2013 Guggenheim Foundation Fellow, she is Associate Professor of English and Creative Writing at Rutgers University-Newark. She lives in Verona, NJ, with her family.