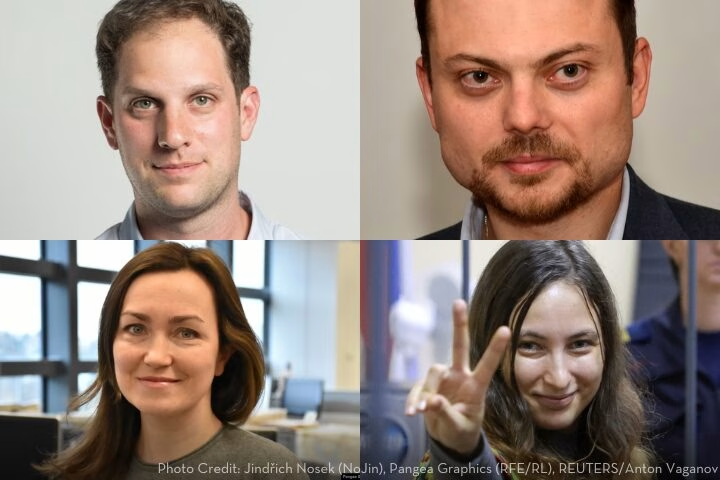

It was cause for joyous celebration when Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich, Washington Post columnist Vladimir Kara-Murza, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty editor Alsu Kurmasheva, and artist and activist Sasha Skochilenko were among those who regained their freedom as part of a historic prisoner exchange.

Yet the words of these brave journalists, artists, and dissidents — and many like them — are still throttled in Vladimir Putin’s Russia, part of a pattern of suppression that has included shuttering independent media and arresting those who dispute the official narrative. This week, Russia barred numerous U.S. journalists from the country, including reporters for The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and Washington Post.

PEN America’s Russian Independent Media Archive (RIMA) – a project developed in partnership with Bard College – aims to counter that suppression by creating a searchable database that preserves more than two decades of work by independent Russian reporters and editors whose newspapers, websites, magazines and television stations have been destroyed or sent into exile.

More than 1,500 journalists have been forced to leave the country, and others remain imprisoned. The result is a new kind of iron curtain drawn around Russia, shielding what happens inside from view for the rest of the world.

“We may not be able to save the journalists themselves, but we can preserve their work and publications,” said Anna Nemzer, a journalist, writer, and documentary filmmaker responsible for the Russian Independent Media Archive’s mission and its media partnerships.

She cites the example of Mikhail Afanasyev, editor-in-chief of the publication Novyi Fokus, which is available in the archive. Mikhail was sentenced to seven years in prison for an article he wrote about 11 riot police officers who refused to fight in Ukraine in the spring of 2022.

Among the more than 5.7 million articles from 58 news outlets now in the archive are those that tell the story of Sasha Skochilenko, the artist and musician from St. Petersburg who was part of the prisoner exchange. Sasha’s story began on March 31, 2022, when she replaced the price tags in the Perekrestok supermarket with anti-war leaflets that challenged the official narrative of the invasion of Ukraine. “Stop the war! 4,300 Russian soldiers died in the first three days. Why is television silent about this?”

On April 11, Sasha was arrested. In prison, her health conditions worsened; she lives with celiac disease and a congenital heart defect. A cardiologist said she might need a pacemaker in six months. After 27 court hearings, Sasha was sentenced to 7 years in a penal colony. In her final statement, she said “Despite the fact that I am behind bars, I am freer than you.”

When Sasha was moved from her cell for the prisoner exchange, she said she believed she was being taken to be shot.

Sasha and several other dissidents were saved. However, there are still many people in Russian prisons who dared to protest against the Putin regime and the war that Russia is waging in Ukraine. In addition, with the start of a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, military censorship was introduced in Russia. The Russian government has censored the internet, banned books from circulation, and intimidated and imprisoned writers of all kinds in order to force state-sanctioned narratives about Russia.

In PEN America’s 2023 Freedom to Write Index, Russia for the first time joined the top 10 jailers of writers. RIMA advisor and journalist Masha Gessen was sentenced in absentia to eight years in prison for “spreading false information about the military.”

Fortunately, RIMA has preserved a more complete version of history. The database is searchable and anyone may request a dataset from the researchers working on the project by filling out a special form about your research. The entire archive is available in English and can be a tool for those covering Russia or wanting to better understand the context.