The Legacy of Martin Sostre (1923-2015)

A Depends advertisement is considered “sexually explicit.”

A map of Westeros “presents a security threat.”

Allowing an incarcerated author to have a copy of their own published work risks the “good order” of a prison.

Books in Spanish could “foment a prison uprising” because guards can not understand the language.

Most people would be surprised to know that prisons vigilantly monitor incarcerated peoples’ reading habits and prohibit them from reading as much as possible. As bad as things are, they used to be worse. According to Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin, in the 1960s and 1970s, no books were allowed in prisons and jails except for the Bible. Even the constitution was once considered contraband. This means that a person could be placed in solitary confinement as punishment solely for reading about their legal rights.

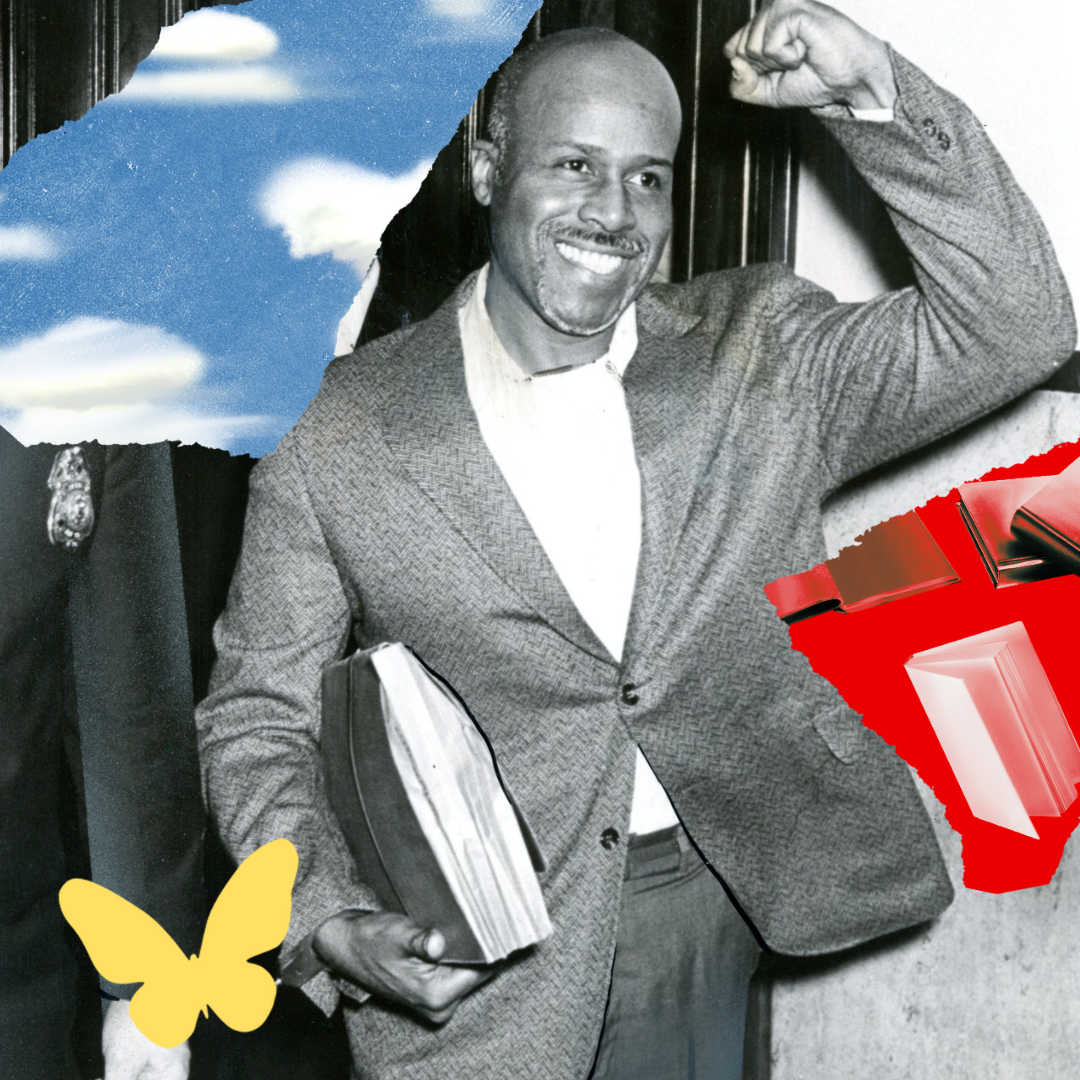

These carceral censorship practices were challenged by a series of lawsuits won by a man named Martin Sostre (1923-2015). Sostre’s legal challenges prompted the creation of the first prison books programs in the United States, which now total 45 and serve all state and federal prisons and jails nationwide. This year would have been the one-hundredth birthday of the jailhouse lawyer and activist. In celebration of Sostre’s achievements and legacy, in March 2023 Garrett Felber organized a two-night event in collaboration with the New York Public Library. Sostre at 100 brought people who knew and worked with Sostre while he was alive, like Kom’boa Ervin, in conversation with organizers like Mariame Kaba and William C. Anderson who have been influenced by Sostre’s writing and lifework. The event could not have come at a more relevant time, as many of Sostre’s groundbreaking lawsuits are being undermined through carceral censorship practices that skirt the laws his litigation forced into existence.

Martin Sostre was born in 1923 in New York City, and grew up in Harlem’s Puerto Rican community. Having dropped out of high school in the tenth grade, he joined the United States Army in 1943. At his station in Tuskegee, Alabama, Sostre ran afoul of the military’s hierarchy and authoritarianism, and returned to Harlem in 1946 after he was dishonorably discharged. In 1952, he was sentenced to twelve years for drug possession. In prison, Sostre converted to Islam and became involved in a 1962 lawsuit that argued it was unconstitutional to deny the Quran to incarcerated Muslims.

It may seem unreasonable that a religious text was denied to people inside. However, Sostre explained during the course of the trial that the Quran, and the Nation of Islam more broadly, was banned because it was used to empower Black men. As the Constitution to the Muslim Brotherhood states, and which Sostre submitted as part of the legal challenge, Islam was integral:

To secure & maintain the complete intellectual unity & awakening of our brothers by promoting the advantages of unity of action and organization through the study of: Islam; our history which has been concealed from us; the struggle for freedom being made by our brothers at home and abroad…

Through his conversion to Islam, Sostre was gaining an increased understanding of his life—that he had been unfairly limited in his options, that people who lived in poverty did not do so because of their own choices or efforts. Prohibiting the Quran was an attempt by carceral authorities to limit awareness of systemic racism so manifestly evident in imprisonment. The court decided in Sostre’s favor, ruling that denial of the Quran unduly limited incarcerated people’s first amendment rights to the freedom of religion. This case was a major victory, and unbeknownst to Sostre, it was just the beginning of his litigation against carceral censorship.

Shortly after this legal victory, Sostre was released in 1964 and he moved to Cold Springs, New York, a poor area of downtown Buffalo that was largely Black due to white-flight. It was here that Sostre opened The Afro-Asian Bookstore, which he stocked with books on Black history and culture, including many on Black liberation. Initially, the bookstore struggled to attract attention, so Sostre began selling music to engage the community. The store quickly became a hub for community connectivity. About his practices, Sostre said:

I taught continually – giving out pamphlets free to those who had no money. I let them sit and read for hours in the store. Some would come back every day and read the same book until they finished it. This was the opportunity I had dreamed about – to be able to help my people by increasing the political awareness of the youth.[1]

Cold Springs was the exact kind of place where information about the roots of social inequality could result in rejection of the existing social order and prompt informed calls for reimagining the U.S. social project. For this reason, Sostre was seen by law enforcement as a threat and was monitored. When local protests erupted in the summer of 1967 in response to anti-Black violence nationwide, the Afro-Asian Bookstore was spared destruction because Sostre opened the store during demonstrations for protestors to rest and organize. For these reasons, Sostre was entrapped by local police collaborating with federal authorities, who recruited a frequent bookstore patron to frame him. This person asked Sostre to hold some money, and a photograph of the exchange was used as evidence for the person’s claim that Sostre sold him heroin. Sostre was charged with “narcotics, riot, arson, and assault.”

Sostre represented himself, using the legal education he taught himself during his first imprisonment. But unlike his previous court cases, during this trial Sostre was literally bound and gagged in the courtroom by the judge’s orders. Partly as a result of his inability to represent himself, Sostre was convicted and sentenced to prison for a second time. It was during this stint that Sostre made his most significant contributions to first amendment rights for incarcerated people as several of his landmark cases forced carceral authorities to repeal censorship practices that had hitherto been commonplace and uncontested.

In Sostre vs. Otis (1971), the court ruled that prison procedures for evaluating literature entering prisons was constitutionally deficient, and therefore had to be revised to protect the first amendment rights of incarcerated persons. Prior to this suit, there were no time limits for evaluating literature. Prison authorities could hold books for as long as they wanted under the auspices of “evaluation,” an easy way to simply deny them in a neverending holding period. The case also established that incarcerated people needed to be informed that they had received a book and, if the book was being censored, provided a justification for why. Additionally, publishers needed to be notified of any literature they published that was rejected by carceral authorities.

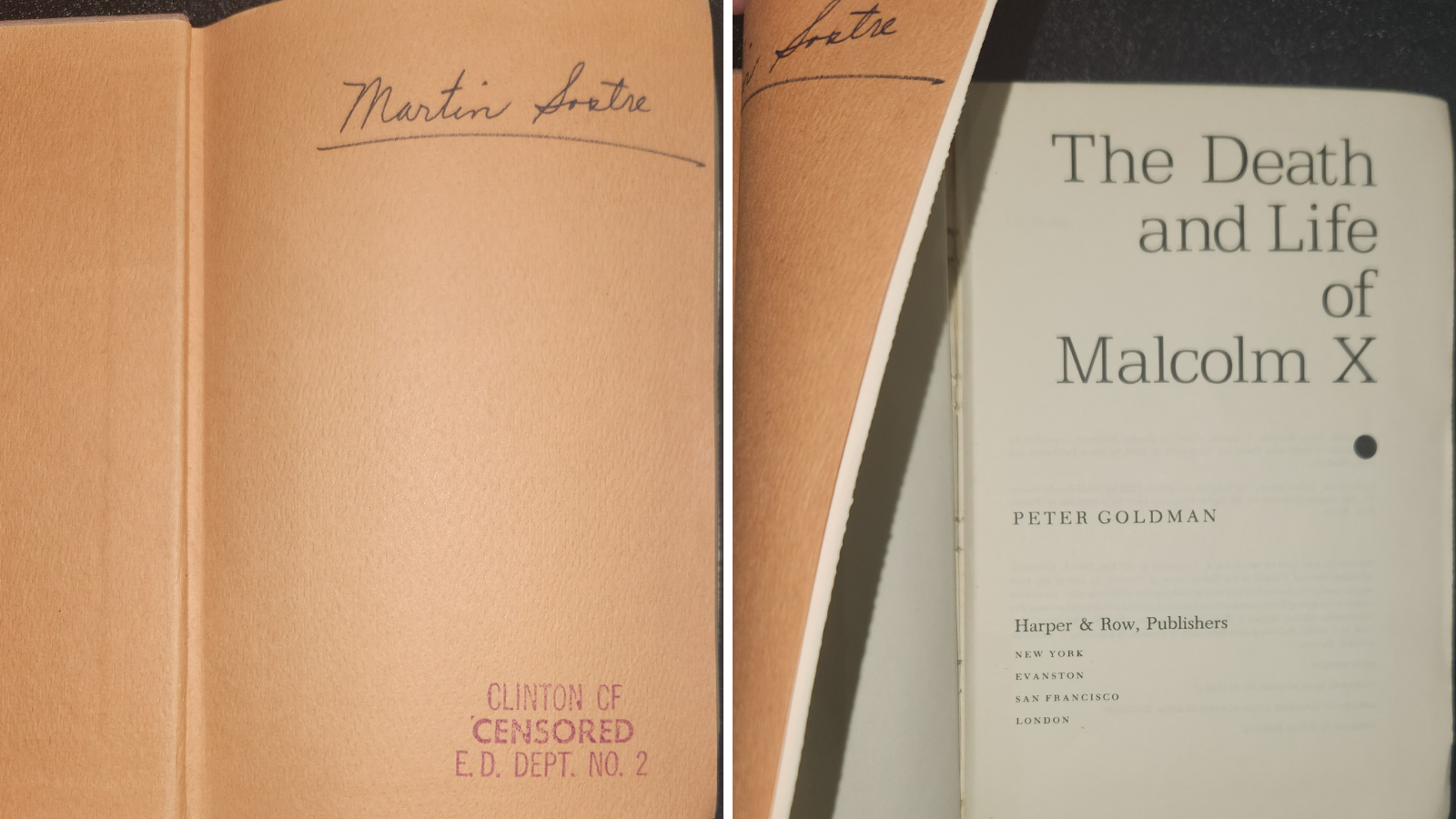

In Sostre v. Rockefeller (1971), the courts ruled that incarcerated people could not be placed in solitary confinement for possessing literature carceral authorities don’t like. In the case, Sostre cites several times he was placed in solitary as retaliation for having “inflammatory racist literature.” Several books from Sostre’s personal library were on display at Sostre at 100, some of which still bore the marks of carceral censorship, including a copy of Peter Goldman’s The Death and Life of Malcolm X (1973). This is also the justification for the witch-hunt on critical race theory at public universities in South Carolina and Georgia and elsewhere. Elected officials in these states claim that teaching the history that laws have been used to enforce racial apartheid, segregation and impoverishment in the United States paradoxically promotes racism.

Sostre argued that incarcerated peoples’ eighth and fourteenth amendment rights were violated, as they were being punished simply for what they were reading. The court affirmed this and ordered several injunctions designed to cease these practices including requiring incarcerated people of the charges as well as a hearing to determine the validity of charges prior to being placed in solitary.

While building these cases, Sostre was also working on challenging his own false imprisonment through legal and advocacy means. The organizing committees of concerned individuals and human rights organizations helped raise awareness about his individual case. The documentary 1974 Frame Up!, for example, features then PEN America President Tom Fleming, who says that Sostre was framed “because he was disseminating and selling books that the local government in Buffalo simply didn’t like.. [and therefore Sostre is] in jail for his ideas.”

Because of this public awareness and pressure, as well as the confession of entrapment by the person who assisted in framing him, Sostre was released in 1976. For the remainder of his life, Sostre devoted himself to creating daycare centers, afterschool programs and other institutions of care in his neighborhood.

Sending books to someone inside may seem a small act in the face of the largest prison system the world has ever known. But, books have been foundational to many incarcerated people. Malcolm X famously taught himself to read in prison from a dictionary. Dictionaries are still the single most requested book for all prison books programs, as they are used to improve literacy. Despite the unmitigated advantages of learning to read, it is increasingly difficult to give incarcerated people dictionaries. From lists of ‘approved vendors’ to regulations that stipulate the specific color of an envelope a book needs to be mailed in, Sostre’s legal victories are being whittled away as states enact regulations that aim to skirt the constitutional basis for free expression.

Although repeatedly debunked, many state prison systems are moving to prohibit paper literature, introducing privately supplied e-readers with a limited selection of materials curated and approved by carceral officials. These tablets have some benefits–people can email and call their loved ones, for example. But, the literature available on the tablets is already censored. People cannot read anything but what is available on the tablet if paper literature is also disallowed. Other state prison systems are grossly limiting who can send books to people inside through lists of “approved vendors.” Michigan, for example, has repeatedly rejected PEN America’s The Sentences that Create Us: Crafting a Writer’s Life in Prison by stating that Haymarket Books is not approved. Rejecting the books initially skirts the injunctions Sostre’s lawsuits established by preventing the books from coming into the prisons at all. These practices continue the carceral censorship Sostre so successfully challenged but less directly.

Sostre’s legacy should be kept alive by continuing his work in pushing back against carceral censorship and countering narratives that justify limiting free expression. While we all are not equipped to make the kind of legal changes Sostre engineered, we can continue to learn more and stay informed about efforts to limit paper books in our local prisons or jails, and contact our elected officials to tell them we are not in support of limiting incarcerated people’s right to read. Joining or supporting a prison book program is also a way to be civically engaged in these efforts. Finally, be sure to sign-up for PEN’s Prison and Justice Writing mailing list to be alerted to more actions we can take to oppose carceral censorship.

[1] Powell, Elwin. “B. Martin Sostre Bookseller Turned Black Revolutionary (1967)”. The Alternative Community in Buffalo, 1965-76. The Buffalonian.

Moira Marquis is the senior manager of The Freewrite Project for PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing Program. She has worked with Asheville Prison Books and co-founded Saxapahaw Prison Books. She is co-editor of the forthcoming volume, Books Through Bars: Stories from the Prison Books Movement (University of Georgia Press, 2024).