Across Katherine Applegate’s dozens of children’s and middle-grade books, a few themes emerge time and time again: empathy, hope, and resilience.

Such is the case with her New York Times bestseller, wishtree, which has been picked repeatedly for community-wide reading programs across the country. The book is told from the perspective of an old oak tree named Red, who urges his neighborhood to welcome a new Muslim family with open arms.

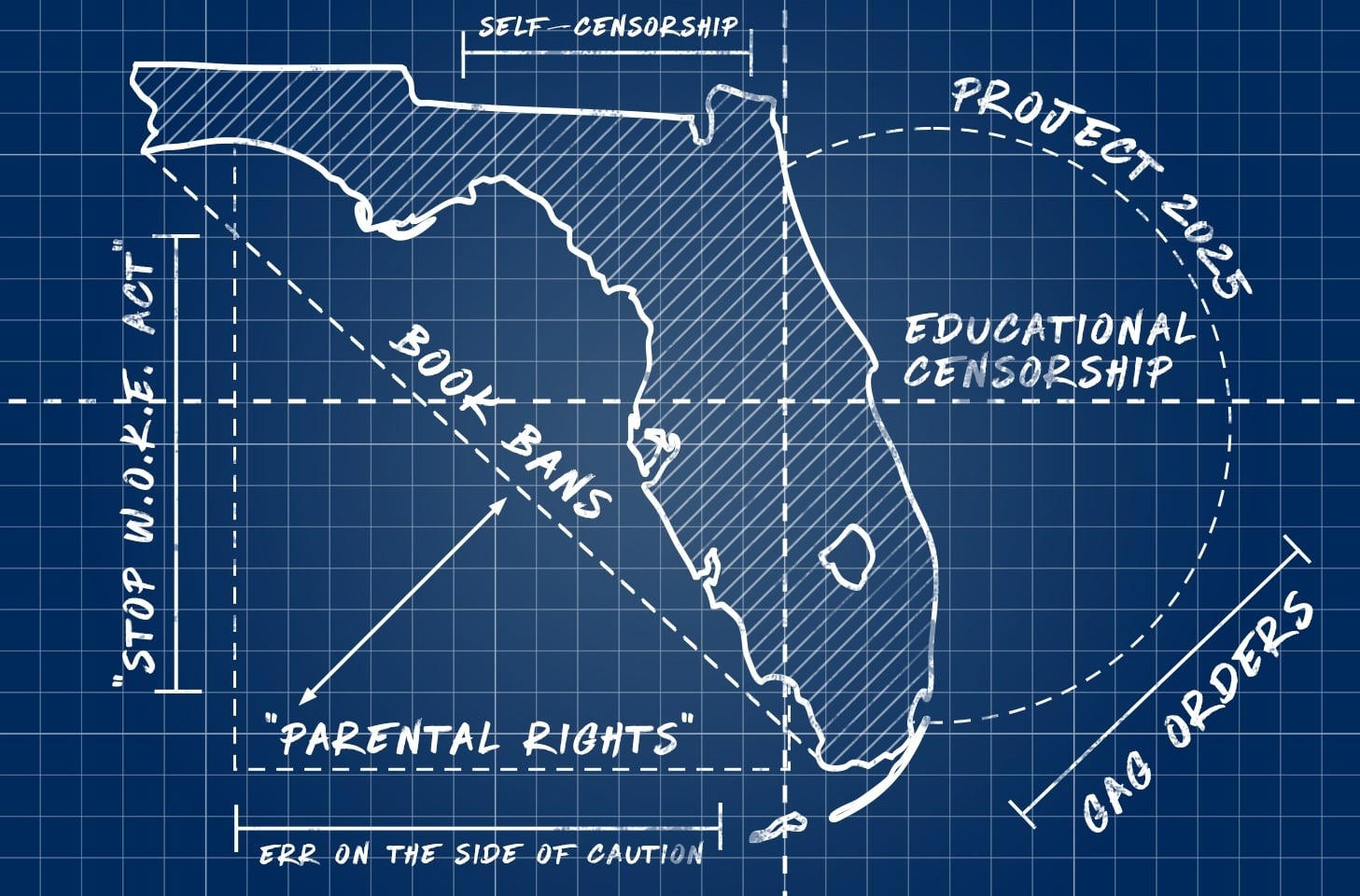

But like so many trees, Red is both male and female (“Call me he. Call me she. Anything will work,” Red says), a detail that has sparked outcry in some school districts. In Wisconsin, one parent called the book “deliberate indoctrination and gender-fluid and non-binary ideology,” and in Virginia, another termed it “indoctrination at its finest.”

In both cases, the extreme response from parents, coupled with a lack of courage on the part of school administrators, led to the cancellation of the readings. And in Applegate’s perspective, it’s likely not just about gender: she’d bet that the book’s stance toward immigrants also played a part in the decisions.

In conversation with PEN America, Applegate describes what children miss out on when adults refuse to let them read wishtree. She also talks about why she’s written a handful of books from non-human perspectives and how literature provides readers with ample opportunities to practice being better people.

Applegate never anticipated that wishtree would receive the accusations and backlash it has. But amid alarming attacks on her book and those of so many other authors, she’s found solace in one place: school classrooms. “When I visit a classroom, I come away reassured that this, too, shall pass,” she told us. “And that the future’s in good hands. We’re going to be okay.”

A Wisconsin school district recently went back on its selection of your New York Times bestseller, wishtree, as its community read because the main character, a tree, is both biologically male and female (as so many trees are). The book was also halted as a community read in Virginia a year earlier for the same reason. Did you ever expect to see this reaction to your book? What’s your response to these worries?

Full disclosure: No one is ever going to accuse me of having a PhD in botany. But when I decided to make a 200-year-old red oak tree the narrator of my novel, I did my due diligence.

Why a Northern red oak (Quercus rubra)? They’re beautiful trees (especially in autumn), easily identifiable and widely distributed throughout North America. And they can live for centuries. I needed a narrator who’d been around for a while because I wanted to talk about the ways a community changes over time, absorbing (and, hopefully, welcoming) immigrant families.

Wishtree was written specifically for a younger elementary audience (I would say the sweet spot is second through fifth grade), but it’s been used in many One School, One Book and One School, One Community reads, where pre-K kids through adults have joined up to read the book.

Given my core audience, I kept things simple, offering up my best guess of What It’s Like To Be A Tree. I touched on photosynthesis. Autumn color change. Root systems. (“In my neighborhood alone, hundreds upon hundreds of us are weaving our roots into the soil like knitters on a mission.”)

And then there was the question of how to refer to “Red,” our narrator. Here’s how Red explains things:

Some trees are male. Some trees are female. And some, like me, are both.

It’s confusing, as is so often the case with nature.

Call me she. Call me he. Anything will work.

Over the years, I’ve learned that botanists—those lucky souls who study the lives of plants all day—call some trees, such as hollies and willows, “dioecious,” which means they have separate male and female trees.

Lots of other trees, like me, are called “monoecious.” That’s just a fancy way of saying that on the same plant you’ll find separate male and female flowers.

It is also evidence that trees have far more interesting lives than you sometimes give us credit for.

When I wrote those words, did I think, “Hmm, some parent with too much time on her hands is going to accuse me of ‘indoctrination at its finest’”? I suppose it crossed my mind for a nanosecond. I’m a fiction writer, after all. It’s my job to imagine the preposterous. But did I think schools would actually suspend readings of the novel in the middle of school-wide reads? Tell kids and parents, without explanation, to simply stop reading halfway through the novel? Honestly, that’s a plot twist I didn’t see coming.

My suspicion is that the “trans tree” angle was the easiest way to object to the book, given the current political climate. But the novel’s discussion of kindness and inclusion—especially when it means welcoming immigrants and refugees—might well have played a role in the challenges.

For the record, if I’d opted to call this novel transtree, so what? And if the targeted family in question had been something other than Muslim—Jewish or Christian or, I dunno, Martian—it shouldn’t have mattered.

I know writers who’ve addressed trans themes in their novels and watched their books banned year after year. These bans don’t just affect livelihoods (although they’ve had a devastating effect on far too many promising careers). They’re not just attacks on titles. They’re attacks on the hearts and souls of good people.

Books are banned because compassion takes work and hate is easy.

What did you want to teach young readers through wishtree? What have kids (or adults) told you they learned from or liked about it?

The catalyst for writing this novel was an article I’d read about a recently arrived immigrant family who came home one day to find a vicious sign posted on their door. (I tell young audiences it said “Go Away.” Trust me: That’s the cleaned-up version.)

I wanted to talk about incidents like that, and do it in a way that would be accessible to young readers.

I often write stories about people from the perspectives of non-human characters, and for this novel, a tree seemed like the perfect narrator. Even better: a wishtree.

Wishtrees, it turns out, are found all over the world. People tie ribbons or pieces of paper on trees, sometimes in a lovely annual ritual.

After reading wishtree, many classrooms, schools, and communities have created their own wishtrees. The wishes are so poignant: I wish I had a friend. I wish my grandma was still here. I wish the world was a kinder place. Sometimes they’re quite charming. I wish I had a pet giraffe remains one of my favorites.

So many teachers and librarians have told me how this book helped their students see beyond their own biases and think about community in a whole new way.

It doesn’t really matter if you don’t like the book. What does matter is realizing the remarkable power of books to help us see the world in new ways.

Why do you think wishtree has been chosen repeatedly for community reads? How can members of a community benefit from reading the same book?

I was not the typical author, the ones who claim they were reading in utero. For me it was a bit of a bore. I was an animal lover; even as a young child, convinced I was going to be a veterinarian when I grew up. Why would I want to read books about made-up things?

Then my third-grade teacher, Mrs. Gray, read Charlotte’s Web to our class. A book about talking animals? Count me in. That was my gateway drug.

That’s the beauty of One Book reads. Reading becomes a shared experience. The crossing guard and your sixth-grade brother and your principal are all reading the same book at the same time. It doesn’t really matter if you don’t like the book. What does matter is realizing the remarkable power of books to help us see the world in new ways.

I’ve been lucky enough to have many of my books used in One Book events. Perhaps the reason wishtree is so often used is because it revolves around the importance of connection and community. The dedication to wishtree reads: For newcomers and for welcomers. When you think about it, we’ve all been newcomers at various times in our lives, haven’t we?

In addition to writing from the perspective of the Red in wishtree, you’ve authored multiple books from the perspectives of animals. In the past, you’ve said that nonhuman narrators allow us to see the world through a fresh set of eyes. What parts of being human do you think we tend to take for granted or overlook?

I’ve written from many unusual POVs, including a western lowland gorilla (The One and Only Ivan), a southern sea otter (Odder), and a chronically disgruntled cat (Pocket Bear). Maybe I gravitate toward those narrators because I’m often confounded by human behavior myself. Outsiders can look at humans and ask “Why are they so gratuitously cruel to each other?” And just as importantly, they can remind us of our breathtaking capacity for forgiveness, for understanding, and for love.

Books allow us to practice being better human beings. Reading about what it means to be a true friend can hopefully help a young reader navigate relationships with fresh eyes.

Many of your books touch on the transformative power of friendship. What draws you back to that theme again and again?

I sometimes say that books allow us to practice being better human beings. Reading about what it means to be a true friend can hopefully help a young reader navigate relationships with fresh eyes.

Did your experience as a reluctant reader influence the kinds of books you write and the way you write them?

Absolutely. I love books with lots of white space on the page to let the words breathe. And I enjoy writing free verse, where every word counts, and there are ample opportunities to hear the music of a phrase.

How have your experiences as a mother affected your perspective on what kinds of literature children should be able to access?

I believe that every parent has the right to decide what their kid reads. Period. End of story.

Just don’t try to tell my kids what they can read.

When I visit a classroom, I come away reassured that this, too, shall pass. And that the future’s in good hands. We’re going to be okay.

Through your picture books, early chapter books, and novels, you’ve taught countless young readers a lot about hope. What have they taught you about it in turn?

Particularly during these past few years, with so many threats to our freedom to read—to our very democracy—I’ve found that doing school visits is the best tonic imaginable. Don’t get me wrong: Adult readers are swell. But writers for children know that nothing compares to the experience of having a kid run up to you, hugging a book, to tell you that it’s the best book ever.

Young readers are idealistic. They’re trying to figure out where they fit in a complicated world. They’re funny and silly and open-hearted. And they’re honest to a fault.

When I visit a classroom, I come away reassured that this, too, shall pass. And that the future’s in good hands. We’re going to be okay. We just need to remember what Jo Godwin, a major advocate for intellectual freedom said: “A truly great library contains something in it to offend everyone.”