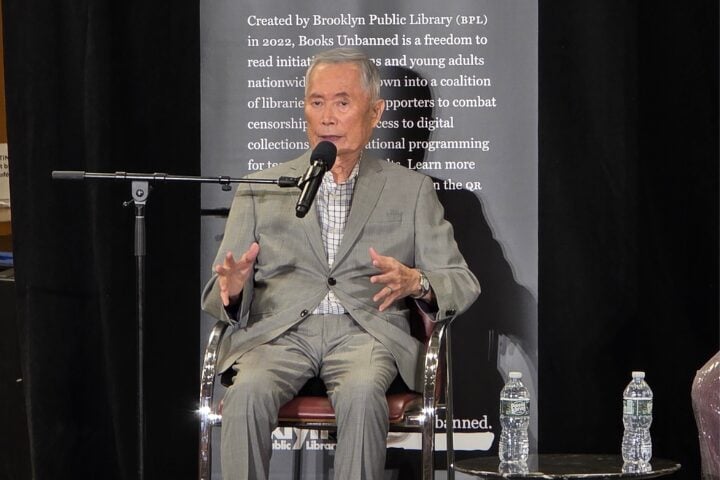

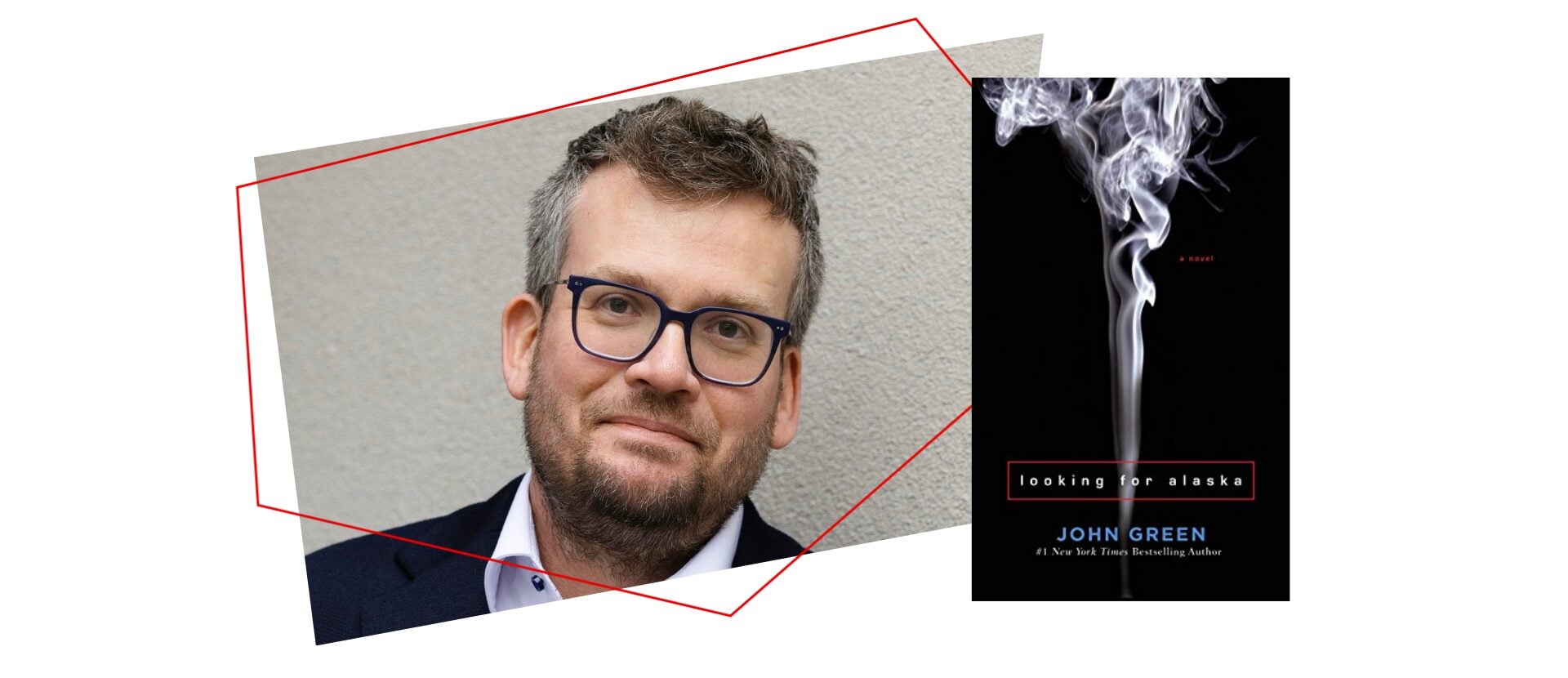

John Green’s debut novel, Looking for Alaska, helped establish him as the leading voice of contemporary young adult literature. It’s a coming-of-age story about love, grief, guilt, forgiveness – and above all, hope.

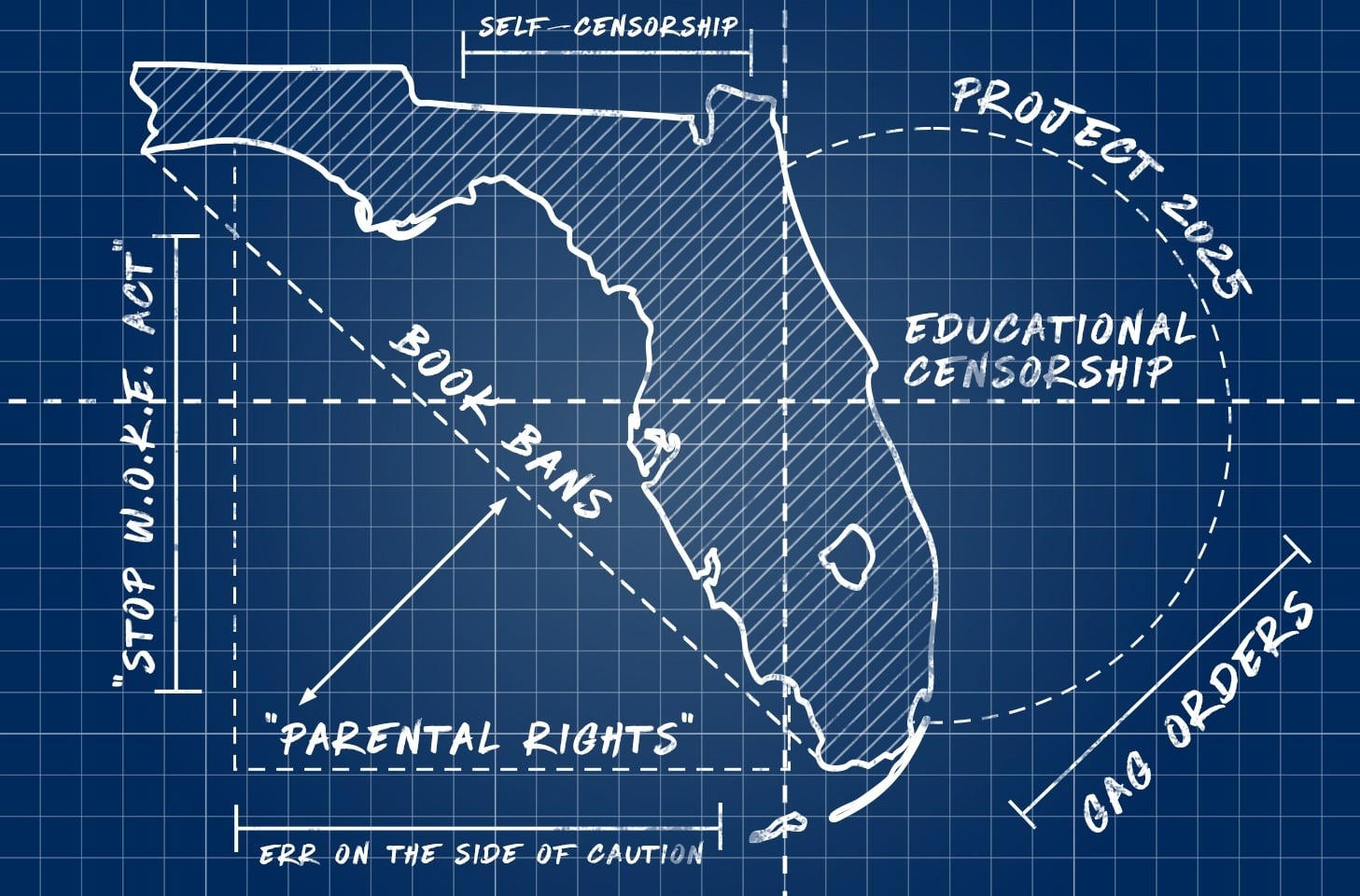

It also includes one short scene of bumbling intimacy. It’s that scene, taken out of context and sometimes read at school board meetings, that has helped make it the most frequently banned book in U.S. schools since PEN America began counting in 2021.

Green calls the number of challenges to Looking for Alaska, which won the Michael L. Printz award for young adult fiction, “strange” and “surreal,” based on bad-faith readings that look for something pornographic in a book about grief and loss.

“People always say it is a badge of honor, but I think it’s become less and less of a badge of honor and more and more cause for concern,” Green told PEN America.

With his sprawling platform – Green and his brother, Hank, have more than 20 million YouTube subscribers to their CrashCourse and vlogbrothers channels and Dear Hank and John podcast, and John Green has another 2.8 million on TikTok – Green feels a duty to speak out about censorship.

He is a plaintiff with Penguin Random House and others in two lawsuits challenging book bans in Florida and Iowa and spoke out after his book was banned from his former high school, in Orlando, Florida, and when it was moved into the adult section of a library in his home state of Indiana.

After publishing his latest nonfiction book, Everything Is Tuberculosis, he’s also found himself lobbying the federal government to restore funding for global public health to fight the disease, which kills 1.5 million people each year despite the availability of effective treatments.

In conversation with PEN America, Green spoke about censorship and the power of books – but left us with his characteristic hope.

Looking for Alaska was published in 2005. Were you surprised to see that it was the most frequently banned book 20 years later?

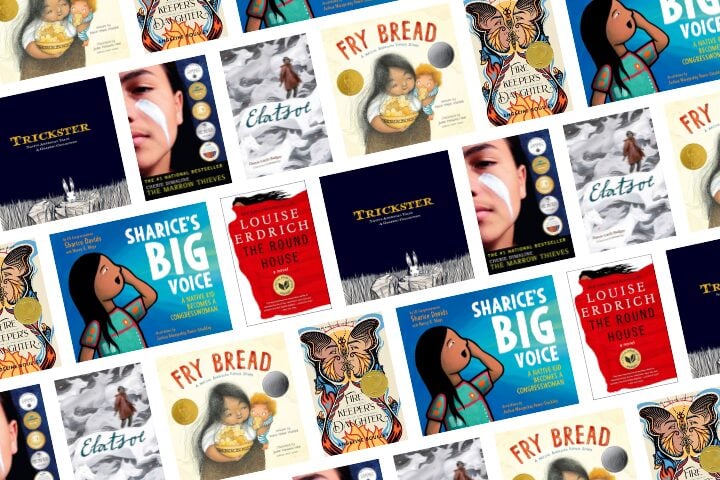

I was surprised, not least because these bans disproportionately affect authors of color and queer authors, and so I was a little surprised to see Looking for Alaska at the top of the list. But in another sense, I’m not surprised, because the book’s been banned pretty consistently over the last 20 years, and so it’s something that I’ve had to come to accept about living with that story.

It seems to be a strange reading of the book. I was seeing objections over LGBTQ content and scratching my head.

Yeah, but I mean, here’s the truth: People are going to find reasons to dislike a book, and that’s fine. There’s nothing wrong with disliking a book. The issue I have is when you try to tell me what my kids can read, and when you try to define what other people’s kids can read. I think that’s very destructive to the social order, and I think that intellectual freedom is a core principle of American life, and it’s disappointing to see so many thousands of challenges and book bans over the last few years. And more than disappointing, it’s, for me at least, pretty scary.

I know you have said that you feel some obligation to speak out about this, even though it has a personal toll. Can you talk a little bit about that toll? Some of these bans have hit close to home.

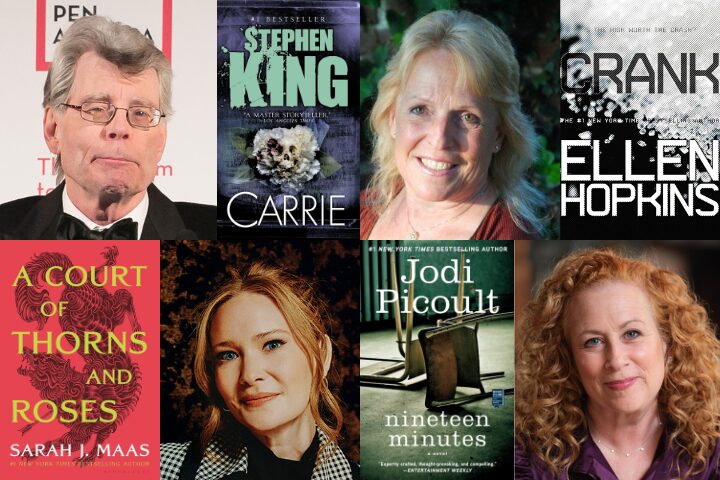

My own high school, my own community here in Indiana. Yeah. Of course, no one wants to be in a situation where you’re walking through the grocery store and someone’s looking at you and thinking that you’re some kind of horrible person who harms children. And I don’t think Looking for Alaska is a harmful book. I think that it’s been in the world for a long time, and people have responded to it really generously, actually, and it’s been really helpful for a lot of people, and that’s something that I’m incredibly grateful for. I worry much more for my friends and colleagues who don’t have the platform that I have who are successfully silenced by book bans. … I look at the breadth and quality of young adult literature today, and I’m really blown away by it. I think that there are so many great books being published, and many of those books might be objectionable to the most radical book banners among us, and yet, still, people are having the courage not just to write them, but also to share them.

Books are a convenient target because they’re in public library systems. And sometimes what’s really being targeted is the idea of a library, the idea of equal access to information and stories.

You are in the rare position of being both a writer and a very online person in the digital age. I’m wondering how you think about the relative dangers and importance of books for teenagers who are spending so much time online.

Well, I don’t think that people would be so interested in banning books if books weren’t powerful. Books are powerful, and stories have a powerful role to play in our lives. They help us to feel less alone. They help us to feel seen and more than that, they help us to see others. I do worry that online experience is affecting our attention span, affecting our ability to read long-form content. I worry that some of the smartest people in the world have been given the most powerful tool in history, and may not be using it in ways that are beneficial to the social order. But I think books retain their power. Books retain their ability to console and give hope.

Why do you think with all of that out there – and now we’re seeing reports that so many teens are not even reading full books in school anymore – why do you think so many people are coming after books?

Well, I think there are a few reasons. I mean, one thing is, you know, books are a convenient target because they’re in public library systems. And sometimes what’s really being targeted is the idea of a library, the idea of equal access to information and stories. I also think that a lot of people don’t understand how a lot of a lot of these quote-unquote ‘concerned parents’ don’t understand the media landscape that their kids are actually engaging in, and so they’re obsessed with books when, you know, they might also be concerned by some of what is on is on Tik Tok. I’m a little biased here, of course, but I think that books are powerful and transformative in readers’ lives in a way that Tiktok just isn’t.

You said something interesting on your channel, which is that books don’t have a gay agenda or a liberal agenda – they have a humanizing agenda. They help us understand the world through someone else’s eyes. What do you think makes that dangerous to some people?

Well, one of the fundamental tenets of certain political beliefs is that some human lives matter less than others, and books challenge that belief by their humanizing agenda, by humanizing people who might be easy to dismiss or marginalize or denigrate. And I think that is a fundamental challenge to the people who hold beliefs that some human lives are less valuable than others.

One of the fundamental tenets of certain political beliefs is that some human lives matter less than others, and books challenge that belief by their humanizing agenda, by humanizing people who might be easy to dismiss or marginalize or denigrate.

You have said you thought Looking for Alaska was a Christian novel, and you are being attacked by a lot of Christian fundamentalists. What are the messages you wanted people to take from this book?

Well, the book is about radical hope and the availability of forgiveness to all people at all times. And as I understand it, those are Christian ideas. But obviously lots of people have different interpretations of Scripture. And that’s fine. To me, it comes back to the question not of what’s appropriate or what you should be reading, but you not telling me what I should be reading. I of course understand that lots of people will disapprove of the themes of Looking for Alaska, or find the content in the book objectionable, that’s fine, but it should be a personal objection, not a not a state-sponsored objection.

Why do you as a writer think including sexual experiences and themes like loss and grief is important in books for teens?

The role of a novel is partly to reflect experience back to the reader. And grief and loss and love are all important parts of being a teenager. One of the really interesting things about being a teenager is that you’re grappling with so many things for the first time. There’s a newness to the way you’re thinking about loss and love and everything else. That’s a lot of why I like writing about teens. I think that denying people artistic access to the full breadth of their experience doesn’t do anyone any good.

You enjoy writing about teens, but it has been a while since you’ve written young adult fiction. Do you feel like in this environment, it’s tougher to do?

No, I don’t. In no way is that a response to these book bans, which have been happening, from my perspective, since 2005 and since long before that. I think it’s definitely something that’s ramped up. It’s something I’m more concerned about than I was five years ago, because I think we’re seeing it spread and become very structured in folks’ attempts to undermine the expertise of librarians and teachers. But it’s always been part of publishing, or it has been for a long time. The reason I haven’t written a YA novel in a long time is just that I haven’t had a good idea. I haven’t known how to respond to my historical moment with fiction. And that’s not, it’s not about book bans. It’s about other stuff.

The role of a novel is partly to reflect experience back to the reader. And grief and loss and love are all important parts of being a teenager.

You seem like someone who’s absolutely full of ideas all the time.

You’d be surprised, though. Book ideas only come to me now and again, but I am writing fiction again. I don’t know how it’ll be published, but I love writing fiction. I missed it during the years when I was away.

In that time writing nonfiction, you’ve spent a lot of time studying history for both your web series and your latest books. What is it about this moment that is making books a target?

Every time in American history and world history, when you see a rise in censorship, you see a coexisting rise of totalitarianism and authoritarianism, and I don’t think this historical moment is any exception.

I think books are a target because they’re important and they have power, and the people who are trying to ban them and remove them from kids’ lives are on some level right to be worried, because books will challenge your worldview. Books will make you understand that human lives are rich and complex, and that the life of every human being matters, and if your worldview can be undone by a book, then I think that I understand why you’re concerned, but I also think the problem might not be with the book, but instead with the worldview.

You’ve taken to lobbying since publishing your latest book, Everything Is Tuberculosis. What has that been like?

It’s been interesting. I’ve learned a lot about the way that the government works. I’m deeply concerned right now. I’m deeply concerned about the funding for global health. Obviously, that’s something that’s really important to me, and that I’ve spent a lot of time trying to work with folks on Capitol Hill on but I’m also deeply concerned about the overall quality and nature of discourse in American life. I think that we are doing a really poor job of talking to each other and listening to each other, and that the structures of the social internet make that worse, not better. And I’m pretty freaked out at the moment.

One of the things that makes me sad is that Alaska used to be taught in hundreds of high schools, and that’s less and less the case, because it’s harder to teach it than it used to be, and that does make me sad.

I know book bans can feel very personal, but it’s the readers, ultimately, who are going to suffer for it.

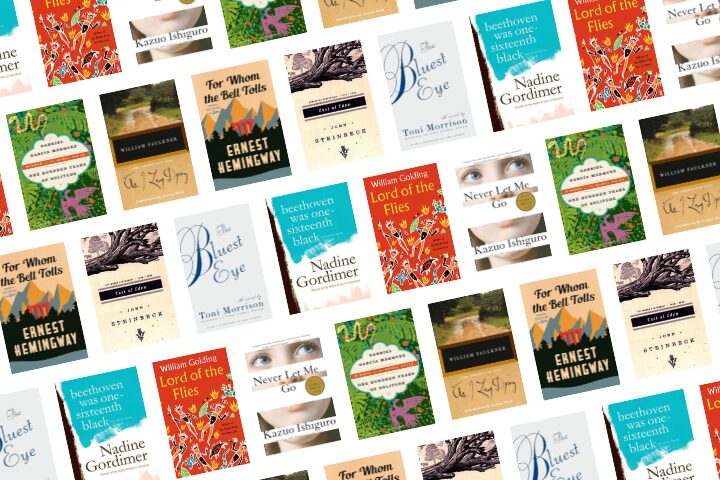

One of the things that makes me sad is that Alaska used to be taught in hundreds of high schools, and that’s less and less the case, because it’s harder to teach it than it used to be, and that does make me sad. But I also, you know, I think about other books that are so important to my own reading life, that have been so transformational to my high school experience. I think about books like Angels in America by Tony Kushner, or a book like The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison, and I don’t know if those books would be taught today, and that just makes me so sad, because it impoverishes the lives of American high school students for no good reason.

And ultimately, the lives of our country. Those people go on to become voting adults who have lost opportunities to learn.

Yeah, absolutely, yeah, yeah, absolutely.

You engage a lot with fans at events and on various platforms. Has anyone spoken to you directly about wanting to ban your book?

Oh, yeah, yeah, a few times, once in a grocery store, once at a book signing. Those are difficult conversations, but I’d rather have them in person than have them on the internet anyway. I mean, I’ve had, I’ve had those conversations a lot on the internet where people will, you know, say outlandish and cruel and and bad faith kind of things to me about my work, about Alaska, especially, but only a couple times in person. And I, you know, those are difficult conversations. I definitely don’t enjoy them, but, you know, I also do want to listen to my neighbors.

We’re all going to live with loss. We are all going to live with grief. And I think stories can be one way that it becomes easier to live with that stuff.

What do you say to them?

I say that I think the book is being read out of context, if it’s being read as pornography and that it’s not titillating or salacious, it’s a book about grief and loss and kids finding ways to go on, and kids who are grieving need those stories.

And kids who aren’t, who might be grieving someday.

Yeah, yeah. We’re all going to live with loss. We are all going to live with grief. And I think stories can be one way that it becomes easier to live with that stuff.

You have said you feel a responsibility to be hopeful in your work, because as you say “hope is the only truth.” Can you help us be hopeful about what’s happening with censorship?

It’s easy to feel like this is the end of the story, because it’s the most recent moment we’ve lived through. But of course, it’s not the end of the story, it’s the middle of the story, and we’re living through a very difficult time in a lot of ways, not just when it comes to censorship, but when it comes to many issues. And we are going to find a way to write a better ending. Organizations like PEN and the Office for Intellectual Freedom at the American Library Association are doing wonderful work to try to bring about a world where censorship isn’t part of the American literary landscape. And I think ultimately, those efforts will be successful.