This post is part of a series from PEN America tracking the progress of educational gag orders and censorious legislative efforts against educational institutions nationwide. These bills are tracked in the PEN America Index of Educational Gag Orders.

The 2024 state legislative sessions have featured some of the most significant and effective resistance to efforts to pass higher education censorship bills that we have seen in recent years. But especially in the latter half of the sessions, censorship advocates have increasingly responded to this growing resistance with a new tactic: trying to achieve the same results without passing a law at all.

It’s working.

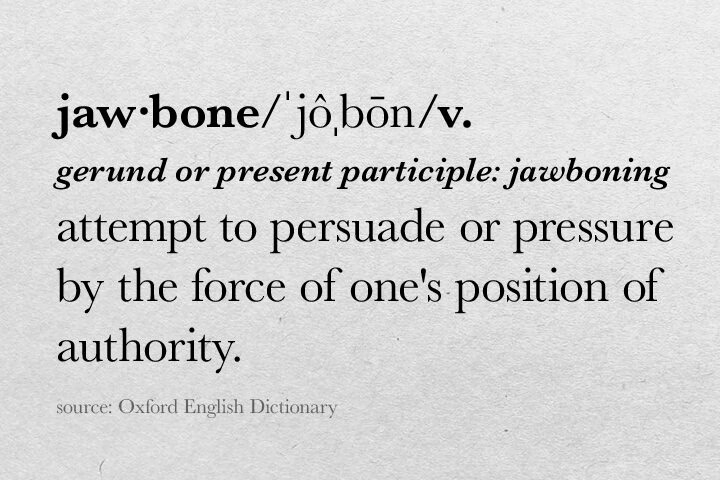

Over the last few months, college and university presidents have been given an Ivy League-quality education in jawboning. Hauled before congressional committees, leaders from some of the country’s most prestigious institutions have been publicly harangued over allegations of antisemitism on campus and their own responses to pro-Palestinian protests. Some resigned shortly thereafter. Others were propelled into disaster. Regardless of where one stands on these presidents and their decisions, we are witnessing the power of the bully pulpit.

But jawboning by politicians isn’t new in higher education, nor is it limited to issues around antisemitism. Over the last year, public officials have aggressively (but often covertly) bullied university leaders into censoring faculty, shuttering university programs and offices, and firing unpopular employees. This sort of behavior rarely receives the public attention that comes with a new law or executive order, but it is no less damaging, and it can be even more difficult to combat.

In this post, we explain how this growing wave of jawboning works.

Case Study: Wisconsin

In June 2023, Wisconsin State Assembly Speaker Robin Vos announced his intention to withhold $32 million from the University of Wisconsin system (later ballooning to $800 million, including money for pay raises and funding for a new engineering building) unless the system first canceled all diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) offices and programming. Wisconsin Republicans had introduced numerous bills in past years to ban DEI, but all had failed to overcome vetoes by the state’s Democratic governor. Vos refused to admit defeat, however, and decided to pursue through political pressure what he couldn’t get done with votes. “So we can’t give in,” Vos said at the time. “This is probably, to me, the single most important issue that we are facing as a people, as a nation, and as really humanity.”

Negotiations between Vos and the University of Wisconsin system continued throughout the summer and fall. Text messages from Vos, acquired by the press via an open records request, reveal a high-stakes pressure campaign going on behind closed doors. In public, Vos was just as aggressive. “We are not going to give the raises,” he vowed. “We are not going to approve these new building programs. We are not going to approve the new money for the university unless they at least pass this deal.”

The threat was simple: if the University of Wisconsin system wanted to avoid fiscal calamity, it would cancel much of its DEI programming. And that’s the way it eventually worked out. In December, the Board of Regents agreed to freeze all DEI-related hiring, abolish dozens of existing DEI positions, and establish an endowed chair in conservative political thought at UW-Madison.

For the university system, it was a total defeat. Policy proposals that had failed to pass through normal legislative processes were in effect implemented anyway. Meanwhile, the whole point of having a Board of Regents is to insulate the institution from this sort of brazen political interference; that interference proceeded unabated. For Vos, though, it was a resounding victory – a victory, moreover, achieved not through the votes of legislators but via political and financial pressure on a governing board.

The Power of Jawboning

Jawboning of this type is the shadowy counterpart to educational gag order laws. It’s also the logical endpoint of a 2024 legislative trend away from splashy rollouts of censorial legislation, touted in press conferences and bill signing ceremonies, that characterized educational gag orders in previous years. In 2023, Florida’s SB 266 and Texas’s SB 17 were trumpeted in the media and at events by the state’s elected leaders; but in 2024 several states enacted educational gag orders in ways designed to avoid debate, publicity, or both. These include Utah’s HB 261, forced through the legislature in just two weeks; a DEI ban added quietly to Iowa’s SF 2435 budget bill in the legislative session’s final days; and a Texas measure opposing antisemitism enacted via executive order.

Jawboning carries this trend even further. Whereas almost all censorial bills must still be introduced and debated through public hearings that provide formal opportunities for opponents to criticize them in public, jawboning typically happens behind closed doors or through informal vectors of power. That means it tends to attract much less attention and provides opponents many fewer opportunities for resistance. It also means that jawboning gives university leaders an incentive to act preemptively, offering concessions to lawmakers in hopes of forestalling the threatened penalties or bills.

Jawboning in Other States

That’s what happened in North Carolina, where in 2023 a group of higher ed critics in the statehouse proposed the REACH Act, an expansive bill authored by an out-of-state conservative activist that would have required faculty to teach US History in a specific way, right down to listing what texts the students would read and how they would be evaluated. Quite correctly, university leaders saw the REACH Act as an attack on the academic freedom of their faculty. Their response, however, was to hastily draft their own version of the curriculum, hoping that doing so might slow the bill’s momentum.

One faculty supporter of the University’s approach speculated that a curriculum adopted by the university system itself would be easier to repeal one day than one imposed by the legislature, and would prove to lawmakers “that they don’t need to intervene, that we are responsive to concerns—but that faculty control the curriculum.” But Mark Elliot, the associate director of UNC Greensboro’s Department of History, was less sanguine. He said of the university system’s concessions: “It’s opening a door, mandating these specific courses or requirements that lawmakers want and mandating what will be taught. That’s a hard door to close again.”

Indeed, North Carolina lawmakers have since pressed their advantage successfully in 2024 again. State House Speaker Tim Moore told the Raleigh News & Observer in April that a legislative ban on DEI in the state’s university system was “at the conversation stage,” but that lawmakers might wait to see if the Board of Governors would “take a look at it first.” Taking the legislature’s hint, the board voted to repeal its systemwide DEI policy the very next month.

Something similar is happening in North Dakota, too. A bill to significantly weaken tenure there failed in 2023 by one vote in the state senate, but only after Mark Hagerott, the chancellor of the North Dakota University System, assured legislators that he was “willing to work with ND legislators to conduct a joint study to examine the post-tenure review process.” This promise was widely seen at the time as a strategy to kill the bill and save tenure. It may have succeeded in the former, but the latter is now very much in doubt. A leaked draft of the subsequent report suggests that university leaders are poised to adopt an even greater weakening of tenure than what North Dakota legislators had initially proposed last year.

In Virginia, jawboning has curtailed faculty control over general education curricula. Earlier this year, Governor Glenn Youngkin’s administration sent letters to George Mason University and Virginia Commonwealth University demanding the syllabi of 27 professors whose courses would be featured in new general ed diversity concentrations. The university leaders took the hint and scrapped the planned concentrations.

And in Texas, university leaders have been cowed into over-interpreting SB 17, that state’s recently passed DEI ban, after a campaign of intimidation by Republican lawmakers. That campaign included a letter from State Senate President Brandon Creighton, who warned universities that without “conscientious efforts” to implement the law, they could face “stringent enforcement provisions, including the potential freezing of university funding and legal ramifications for non-compliance.”

The consequences of this jawboning in Texas have been particularly drastic. Despite an explicit carve-out in the original bill for guest speakers, activities organized by student groups, and programs focused on student recruitment, Texas universities have cited the law when canceling a talk by a Queer scholar, blocking a student trying to arrange LGBTQ+ activities on campus, permanently closing a student multicultural center, ending a program that provides scholarships and support to undocumented students, and firing hundreds of employees. Here, the political threat of overenforcement has led universities to justify censorial actions that contravene the plain language of the original law.

Conclusion

So long as jawboning continues to bear fruit, expect more tactics like this in the future. For those looking to censor higher ed, passing a law is a high-risk, high-profile undertaking, one that invites powerful resistance and often ends in defeat. Far better, therefore, to flex one’s political muscles in less obvious ways. A private email, a public shaming, or a threatening remark at a fundraising gala or press event, can do just as much damage to academic freedom and free speech on campus as a law – so long as university leaders respond in the ways lawmakers expect them to.

For successful university leaders, the prudent management of risk is a necessary qualification for the job. But educational gag orders turn that strength into a weakness, as leaders over-enforce vague laws and magnify their chilling effect. Jawboning represents the natural endpoint of this process: lawmakers issue threats and drag professors and staff through the mud, then sit back and watch as university governing boards and administrators do the censors’ work for them. Until university leaders adjust to this tactic, and recognize that maintaining the autonomy of their institutions requires a willingness to defend themselves against political bullies, jawboning will continue to be an effective tool of censorship.