from Ithaca Forever

PEN America is thrilled to showcase the work of recipients of the 2017 PEN/Heim Translation Fund Grants. For the next few weeks, we’ll feature excerpts from the winning projects introduced by the translators themselves. The fund awards grants of $2,000–$4,000 to promote the publication and reception of translated world literature in English.

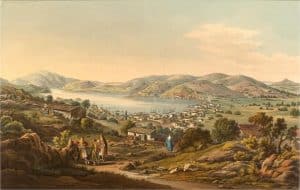

Douglas Grant Heise is the inaugural winner of the PEN Grant for the English Translation of Italian Literature. Today we feature an excerpt from his grant-winning translation of Ithaca Forever, a novel by Luigi Malerba. First published in 1997, Ithaca Forever is a rewriting, from a fresh new perspective, of the return of Odysseus to his native island.

Heise writes: I stumbled onto Luigi Malerba a few years ago through another translation I was working on, an experimental fictional Italian travelogue. In that book, the narrator finds himself reflecting on the short stories in the oral tradition of one Luigi Bonardi. After looking it up, I was surprised to discover that Bonardi was in fact the real name of Luigi Malerba, a prized and prolific Italian author and literary figure of the twentieth century whose books I had never even heard of, much less read.

In Malerba’s Ithaca Forever, I found a book of subtle interior investigation, a re-reading of a small part of the Odyssey with an extremely personal vision, a novel in which two characters—Odysseus and Penelope—engage in an intense battle of wills, deception, and stubbornness. The book sustains a heightened drama in spite of the fact that we all know the story, and the depth of the characters, adrift in all of their doubts and recriminations, leaves a powerful imprint on the reader. Penelope in particular becomes the most intriguing figure in the work and reserves a number of surprises both for her husband and for us.

What’s more, I found that Ithaca Forever, despite having been Malerba’s most popular and best-selling novel in Italy, had never been published in English. Only two of his many excellent works have ever been translated into English, both by William Weaver in the late 1960s, which made me feel a heightened sense of responsibility and trepidation toward this novel. It was a project that I felt driven to try to bring to the English-reading world, and the choice by PEN America to honor my work with this grant has been a thrill and, hopefully, a sign that someday Malerba will once again be a novelist with a following among English-speaking readers.

The short excerpt here comes from the opening pages of the novel, when a confused, indecisive, and unsure Odysseus—quite the opposite of his canonical persona—awakens on the shore of Ithaca after his 20-year absence.

*

Odysseus

I’ve often asked myself how the sea can be salty when the rivers that flow into it are not, nor is the rain that falls from the sky. I’ve never found an answer, and now, awakened from a deep sleep by the wind, I ask the question anew as I sit here on the rocky shore of this land that I know should be Ithaca, but which I do not recognize.

I look around, disoriented because I do not recognize the rocky coast, or the arid land covered by leafless wind-swept trees, or the mountainous horizon, or the sea-blue sky above me. And I wonder where these fragments of porous red rock come from, carried down from the mountains by rushing rains. With every storm, another piece of the world falls into the sea, dragging down dirt and stones, leaving behind holes and naked tree roots. Will the sea someday become one great plain, filled in by the debris of vanished islands and mountains?

Many years ago I hunted for deer and boar in the mountains of my Ithaca, from one peak to another, but I don’t remember ever walking over this red sponge-like rock that I find around me, made spherical by the wind and waves. Where does sea salt come from? Where do all these red sponge-like rocks along the shore come from? Where on earth am I? Did the Phaeacian sailors drop me off on the shores of Ithaca, or somewhere else? I’ve never trusted sailors, who I know are the greatest liars in the world.

The difficulties of the war and my long voyage have made me suspicious of everything, so I suspect that the Phaeacian sailors who brought me here waited until I was asleep and then dumped me on the shore of the first deserted island they could find. This way, they could rid themselves of an unwelcome guest once and for all and steal the gifts that their generous King Alcinous had loaded onto the ship for me. I could see in their restless features that they wanted nothing more than to sail the high seas in search of fortune before returning home. But if they had wanted to claim my treasure for themselves, they would have just thrown me overboard into the deep salty sea at night, rather than land on this craggy coast. Maybe they wanted to steal the treasure but didn’t want my death on their consciences. Who knows? Fellow feeling sometimes survives even in the hardest of hearts.

But over there, I see something shining underneath the branches at the base of an olive-green shrub at the entrance to a deep cave. There they are, the gold and silver cups and plates that the king of the Phaeacians presented to me before my departure. I’ll hide them better with another layer of fronds and some heavy stones so that no wanderer can make off with them.

I still don’t know if this land is my native Ithaca, or some other little island adrift in the ocean, or simply some unknown coastline. I don’t know if this land is inhabited by hospitable men or by giants with a single eye in the middle of their foreheads. I look around but still don’t know if I am home.

I ask myself how this arid and wild land can be the homeland that I dreamed about for nine long years of war and another 10 years of treacherous and adventure-filled voyages. I know that the memory of home can be unreliable indeed. During the years I was away and in times of danger, I imagined my rocky island to be as green and full of flowers as a garden, though in truth it is only good for nourishing flocks of sheep and goats that graze on dry grasses growing between hard rocks, and for herds of pigs that grow fat on the acorns that fall in the wooded highlands. I have finally learned that you should never try to make dreams match up with reality.

But I am not telling the whole truth when I say that the years under the walls of Troy were long for me; in truth, they were the fastest years I have ever lived. Hard, happy years. And I can even boast of how I personally was decisive for the victory of the Achaeans. I call it a victory, but who knows if victory is the right word for the destruction of a city and the atrocious events that took place beneath its walls, and which I myself have recounted as moments of glory a hundred times during the stops on my long voyage back.

I left dressed in the robes of the king of Ithaca, and now I’m going to re-enter my house dressed in the rags of a beggar that I found in this cave at the edge of the sea, and which will allow me to observe secretly–and, thus, truthfully–what has been going on during my absence. To learn if what I have heard is true, that my house is full of admirers vying for the hand of Penelope, hoping to take my place in my palace and in my bed. How Penelope behaves with these admirers. How Telemachus has grown since I left him behind as a baby. What condition my lands are in. How the servants and handmaidens have been acting in my absence.

Twenty years thrown to the winds? Twenty years without a memorial? Who knows if anyone will ever collect the survivors’ stories about the feats of Achilles, Hector of Troy, and Agamemnon of Mycenae, warriors of great heart but limited mind, of their anger and cruelty, and especially of the story of the wooden horse that I invented and which allowed us to conquer Troy and return the beautiful Helen to Menelaus of Sparta.

When I think of the struggles, of the wounds, and of the lives lost because of an unfaithful woman like Helen, my mind grows muddled. But when I ignore the cause of the most idiotic war in the world, then I, too, want its history to be carved in the lasting stone of memory for generations to come, those events that will never repeat themselves and which have already been consigned to antiquity.

No woman shall give birth to men like Achilles, Hector, and Agamemnon ever again. The Sparta of Menelaus and Mycenae of Agamemnon were constructed under the clash of arms and will last as long as the stones with which they were built, which is to say a miserable fraction of eternity. But memory deceives and history is a liar, because men want to remember and listen to fairy tales, not to brutal, stupid reality.

Many things have happened to me in these 20 years, but how many other things must have happened in Ithaca while I was gone? If I can’t even recognize my own homeland, which has remained unchanged for centuries, I wonder how much Penelope will have changed, or how I will ever be able to recognize my son Telemachus, no longer a babe in his crib but a full-grown man. How much can a husband and a father who has been so far from his home and his family for all these years count on their love?

And so I’ll be on my guard. I’ll sneak into my house without being recognized, acting as carefully as my experience tells me to. Who knows if I can depend upon Telemachus and on Penelope’s devotion, she to whom I have sent my noblest thoughts every day, even amidst the sound of battle and the roar of tempests.

Your children are your children even if they don’t know you, even when circumstances make them hate you, but a cheating wife becomes a stranger, unbound to you by relations or blood. I never once doubted Penelope in all these years, so why do questions assail me now, just when I have finally set foot on what I hope are the arid soils of my Ithaca? When the crashing waves threatened my ship, when the winds snapped the strong mainmasts that held my sails aloft, my thoughts flew to Penelope awaiting my return, and the thought of her gave me the strength to fight against all the adversities that jealous gods placed in the way of my homecoming.

Why am I now afraid that I have lost the only reason for my embattled return home? Why now, just when trustfulness would be a warm bed for my exhaustion, do the embittered gods once again resist me and confound my mind with all of these doubts? For years my ears have heard their noisy celebrations high on Olympus after their daily banquets, but I don’t hear them anymore, and the bright shell in which I listened to the sound of Penelope’s voice was left behind on the ship. The loss of the shell is harder to bear than the loss of the drunken gods’ voices. But why should I lament the loss of this shell when soon enough I will be able to listen to Penelope’s voice in person?

If I raise my eyes to the sky, I can see black hawks with their angular wings, gliding on high as if motionless against that deep blue. If memory doesn’t fail, I remember that hawks were rarely seen in the skies above Ithaca. Should I thus think that the farmlands have been left to grow wild and that snakes—the prey of raptors—have taken over?