Free Speech & Hate: History’s Lessons

Between 2021 and 2023, PEN America and the American Historical Association (AHA) cohosted Flashpoints: Free Speech in American History, Culture and Society. This series presented the fascinating and complex history of free speech in American democracy to public audiences in cities across the country. The historical flashpoints highlight pivotal moments in which artists, activists, writers, filmmakers, and intellectuals tested the limits of free speech, challenged the public to redefine “freedom” and realized it anew for populations and causes that were at risk of having their liberties denied.

How to Use this Guide

This guide was designed to supplement the video recording of a live event for use in the classroom. The questions and prompts included here offer ideas for fostering student engagement in both secondary and postsecondary educational environments, foregrounding issues of general public interest that align with topics often covered in history, government, civics, and political science. Choose the prompts that seem best suited to the concerns and interests of your community, using them as a springboard for discussion, writing exercises, and debate or as a model for civic engagement.

Incorporating Flashpoints into the secondary classroom

The video recording of Flashpoints: Free Speech and Hate: History’s Lessons and discussions of the flashpoints can help structure lessons on the First Amendment, free speech and hate speech, race, media and art, and legal policy. The classroom activity below expands on Karlos Hill’s idea of “learning how to care.”

There are a number of museums, digital archives, and collections that easily can be incorporated into classroom discussion and activities. Allow students to explore the images, newspapers, and other sources available on The Gateway to Oklahoma History (gateway.okhistory.org), a historical database from the Oklahoma Historical Society. Instructors can let students explore the site with search terms like “Tulsa Race Massacre” or “Tulsa Race Riot,” experimenting with the filters (dates, resources type, and collections are particularly useful). Have them share what they found, in groups or to the whole class. Note the language and tone of the items. What do words like “riot” indicate about who is taking action and who is being acted upon? Why do many historians now prefer to describe what happened in Tulsa as a “massacre”?

Using online databases, students can explore primary sources, including photographs and newspapers, from the aftermath of the Tulsa Race Massacre. This exercise will ground a discussion in a historical context, as the panelists did, as well as explore an event in American history that highlights the tension of freedom, speech, race, and violence that characterized the panel. It may be useful to show Victor Luckerson reading from his New Yorker article to help ground this activity (3:45). Other sources that can be used to prime this discussion are listed in the suggested readings below.

Learning Outcomes and Standards Alignment

The question of free speech and hate can orient an inquiry that aligns with the C3 Framework, especially as it applies to both US history and civics education. A lesson built around this video, activity, and subsequent discussion can address D2.His.1-3 on change, continuity, and context; D2.His.4-8 on perspectives; and D2.His.9-13 on historical sources and evidence.

The classroom activity described in this guide, which asks students to delve into contemporary accounts of the Tulsa Race Massacre in the press, will move firmly into dimensions 3 and 4, requiring students to gather and evaluate sources; develop claims and use evidence; communicate and critique conclusions; and, potentially, take informed action.

Many states will have standards in civics, social studies, or history that address free speech, the Bill of Rights, Supreme Court rulings, Reconstruction, the Jim Crow era, and/or the Tulsa Race Massacre.

Free Speech & Hate: History’s Lessons

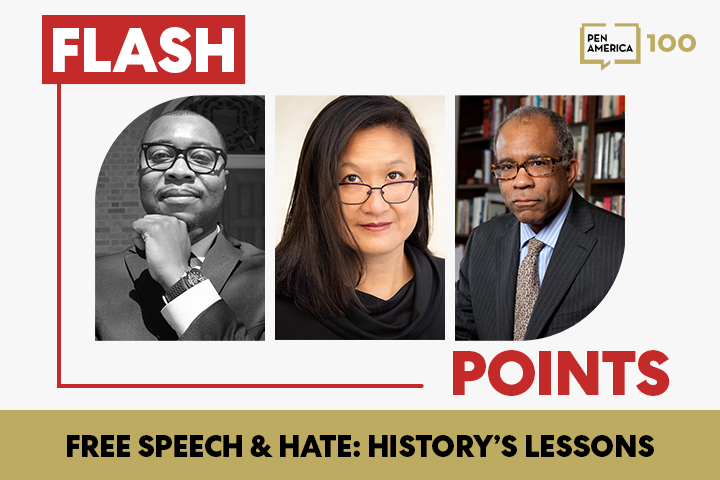

On April 27, 2023, Jennifer Ho and Randall Kennedy joined moderator Karlos K. Hill for a conversation about Free Speech & Hate at the Tulsa Press Club in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Should the right to free speech extend to the right to engage in hateful expression? At many points in US history, the First Amendment has been invoked to protect the freedom to denigrate people and groups. From decades-old media like The Birth of a Nation, a film that celebrated the racist ideologies of the Ku Klux Klan, to recent legal battles over the reclamation of racial slurs as seen in Matal v. Tam, the question of just how far free speech should go is the focus of this panel discussion. This discussion tackles the question of how a diverse, democratic society can defend free speech while also standing up to bigotry.

What is a Panel Discussion?

The format of a panel discussion, in which multiple experts gather to talk about an issue of compelling public interest, provides a model for the kind of informed, civil dialogue that teachers hope to facilitate in the classroom and that is vital to the functioning of a democratic society. Many students may be unfamiliar with this style of intellectual exchange because people argue, rather than just deliver definitive facts. Teachers or discussion leaders may wish to call attention to the fact that each panelist has devoted years to the careful and thorough study of the topic they are addressing. Note, too, how each speaker anchors their interpretation in specific examples that provide evidence to support their perspective.

Informed debate can look quite different from the kinds of sparring matches students see on the news. The panelists may agree about some ideas but not about others. Grappling productively with reasonable differences in interpretation is essential to developing a full understanding of an issue. This kind of conversation—in which experts gather to discuss their findings—is an important component in the creation of new knowledge about our society and the world.

- Is this panel discussion different from debates we see on cable news? If so, how and why?

- Can we, as a class or discussion group, engage in a civil debate in our own class discussions?

Free Speech & Hate Video Timeline

0:00 – Introductions of PEN America and moderator

3:45 – Victor Luckerson reading his New Yorker article “Living in the Age of the White Mob”

12:42 – Karlos Hill introduces panelists and makes opening remarks

19:50 – Randall Kennedy on the film The Birth of a Nation and Black activists’ efforts to censor it

35:05 – Jennifer Ho on Matal v. Tam and reclaiming racial slurs

52:10 – Panel discussion on free speech and hate speech, teaching, and costs of hate speech

1:03:25 – Panel discussion on possible exceptions and limitations of free speech, including some current and past contestations

1:18:10 – Audience questions

The Flashpoint: Tulsa Race Massacre

On May 31 and through the night to June 1, 1921, mobs of white residents in Tulsa, Oklahoma, attacked Black residents of the city’s Greenwood District. Greenwood was one of the wealthiest Black communities in the United States, coming to be known as “Black Wall Street.” The community was held up as an example of Black success in the nation by Black advocates at the time, including Booker T. Washington. However, Oklahoma had adopted several Jim Crow policies following statehood in 1907, and the popularity of the film The Birth of a Nation led to a resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan across the United States, including several thousand members residing in Tulsa.

The catalyst for the massacre occurred when Dick Rowland, a 19-year-old Black shoeshiner, was accused of sexually assaulting Sarah Page, a 17-year-old white elevator operator. Rowland most likely tripped into the elevator and grabbed Page for support, causing her to scream. Police arrested Rowland, and word of the alleged assault spread, leading to white residents organizing a mob with the intention of lynching Rowland. A group of armed Black residents arrived at the courthouse to prevent the lynching, and, while they were leaving, someone fired shots and violence erupted. Local police, National Guard units, and other local and state officials mobilized to stop the riot, though some participated in the destruction of Greenwood and the detention of nearly all the Black residents in Tulsa. Those who did not flee were interned for several days. In the aftermath, somewhere between 70 and 300 residents were killed, Greenwood was destroyed and looted, an estimated 10,000 people were left homeless, and over $2.5 million in damage was done (roughly $37 million today). Now, after more than a century, the Tulsa Race Massacre is receiving more scholarly and national attention. Students in Oklahoma are much more likely to learn about the event, which was not the case even a few years ago. The city of Tulsa, the state of Oklahoma, and the United States continue to grapple with the impact of this event. And now, you will have that opportunity as well.

- What is hate speech? Do you think hateful depictions of certain groups of Americans can help to understand and explain violence against these groups?

- Can you think of other examples in which journalists or politicians blame hateful speech for instances of violence?

Activity: Reporting on the Violence in Tulsa

Once students have learned how to use a source database, direct them to explore newspaper coverage of the event and note what they observe from coverage of the massacre. They can search by date (May 31, 1921, and a week or more after) or by publication. The Black Dispatch was a Black-owned newspaper published for a Black audience located in Oklahoma City, and the Tulsa Tribune and Tulsa World also covered the event. Have students discuss the differences they observe in the coverage. Who were the perpetrators? Who were the victims? What happened and whose perspective was given?

As a larger group, you can bring in other examples discussed during the panel discussion. Does the media coverage of the Tulsa Race Massacre you’ve just read appear to be free speech? Racist propaganda? Where does the tension of free expression and hate speech in media emerge in this example? What may be the costs or consequences?

Free Speech & Hate: Censoring The Birth of a Nation

The film The Birth of a Nation (1915) was one of the most expensive, profitable, ambitious, technically revolutionary, and controversial films of its time. President Woodrow Wilson held a screening at the White House, the first film ever to be shown there. As Randall Kennedy notes in his synopsis of the film, The Birth of a Nation dramatized the period of Reconstruction following the Civil War. Its director, D. W. Griffith, portrayed Reconstruction as a tragedy and the Ku Klux Klan as the Redeemers, or saviors, of the South—and the United States as a whole—by restoring order and virtue as well as white supremacy.

Reconstruction was significant, particularly for the number of Black people engaging in politics and holding public office. Over 2,000 Black people held offices ranging from local officials to US senators. However, the film depicts these individuals as “ignorant” or “brutes,” as Kennedy describes. These racist depictions drew criticism from several Black advocates and activists after the film’s release. James Weldon Johnson (25:16), W. E. B. Du Bois (26:35), and others critiqued the film and sought to censor it. A few states and cities banned the film, but activists achieved only marginal success. The campaign against The Birth of a Nation pit freedom of expression, which as Kennedy notes is essential for minority communities, against censorship of what Black advocates called “racist propaganda.”

- Karlos Hill poses the opening question: Why is the history of attempts to censor The Birth of a Nation important for the notion of free speech? How does Randall Kennedy respond and how does he reach his conclusion? What historical examples does he use? Do you reach the same conclusion?

- Kennedy details the depictions in the film of Black people and the Ku Klux Klan, a bit of the history, and the responses by Black advocates to those depictions. Does the film depict Reconstruction as a tragedy? If so, a tragedy for whom and why? What impact does that interpretation of Reconstruction have (i.e., the popularity of the second iteration of the Klan, the mainstream adoption of the “Lost Cause” narrative of the Civil War and Reconstruction, reaffirming racial assumptions, etc.)?

- Kennedy closes on a final tension (30:40): He is glad the effort to enlist government censorship failed and the “habitual defense of expression” was reinforced, even in the instance of this “evil” film. Both Kennedy and Hill (57:00) raise provocative questions about what happens when governments choose between protecting hateful speech and protecting the subjects of that hatred. Whose speech is likelier to be protected? Who benefits and who bears the consequences?

- As the panelists note, using the First Amendment to protect hate speech can come at a serious cost. Can you think of any examples, whether cited by the panelists or not, when hateful expression has resulted in real harm?

- The Tulsa Race Massacre occurred a few years after the release of The Birth of a Nation. The film alone did not cause this violent outburst. As an example of “racist propaganda,” however, it seemed to celebrate violence against Black communities. Can the popularity of The Birth of a Nation help us understand the causes of the massacre? Can freedom of expression be worth the costs if and when there is a possibility for those costs to be so high?

Legacies of Free Speech & Hate: Matal v. Tam and Reclaiming Racial Slurs

In the early 2000s, Simon Tam formed a band made up predominantly of Asian American musicians. When deciding on a name based on their common identity, the members chose “The Slants” based on stereotypes that they faced. In their childhoods, members had been bullied for being Asian American, and so they wanted to reclaim the slur and “take ownership” of Asian stereotypes. There were several other bands with that name, so Tam applied for a trademark in 2009. Based on the “disparagement clause” of the Lanham Act of 1946, the trademark was denied. According to Jennifer Ho’s summary, the rationale for the denial was that if the applicants had been white and used the name without invoking the Asian stereotype, then the trademark would have been approved. The case was appealed to the Supreme Court in 2017. The court ruled unanimously that the disparagement clause was in violation of free speech. The band stopped playing in 2019 and started an organization to promote arts and activism.

- The rejection of Tam’s trademark application cited the “disparagement clause.” Can the action of reclaiming a slur or stereotype be disparaging? Do the intentions of Tam and his bandmates matter when answering this question?

- Jennifer Ho plays a portion of a song from Tam and the band. She notes that the band members were often asked about the case and its impact leading up to the Supreme Court decision. Yet no one focused on their music, which is what the band members seemed to care most about. What happens when the implications of a case overshadow the art at its core? What impact does that have on the artists and their goals?

- Ho describes her discomfort with the implications of the case and how she would view it if some details were different (49:20). Ho illustrates how diverse hate speech can be and how she would react to different forms, like on social media (1:15:25), or speech using different words. Do those different words or forms matter? If hate speech is multifaceted, should efforts to limit or prevent it also be multifaceted?

- Ho describes her experiences and relationship with hate speech and provides several examples from others. Some students may have had the same or similar experiences, while others may never have experienced hate speech. During the Q&A, Karlos Hill says that he encourages his students to “learn how to care (not just learning)” about these and other issues. What does it mean to learn how to care? Do you agree that this is a worthwhile goal? What steps can we, as a group, take to facilitate this kind of learning?

Suggestions For Further Reading

“1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.” Tulsa Historical Society and Museum. https://www.tulsahistory.org/exhibit/1921-tulsa-race-massacre/

Chang, David A. “The Battle for Whiteness: Making Whites in a White Man’s Country, 1916– 1924.” In The Color of the Land: Race, Nation, and the Politics of Landownership in Oklahoma, 1832–1929, 175–204. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Halliburton, R. “The Tulsa Race War of 1921.” Journal of Black Studies 2, no. 3 (1972): 333–57.

Messer, Chris M., Thomas E. Shriver, and Alison E. Adams. “The Destruction of Black Wall Street: Tulsa’s 1921 Riot and the Eradication of Accumulated Wealth.” American Journal of Economics & Sociology 77, no. 3/4 (May 2018): 789–819.

Teague, Hollie A. “Bullets and Ballots: Destruction, Resistance, and Reaction in 1920s Texas and Oklahoma.” Great Plains Quarterly 39, no. 2 (May 4, 2019): 159–77.

Acknowledgements

PEN America would like to thank the National Endowment for the Humanities for their generous funding, which made “Flashpoints: Free Speech in American History, Culture, and Society” possible. We would also like to thank the American Historical Association for their contributions to “Flashpoints” and the Discussion Guides. In particular, special thanks are awarded to Alexandra F. Levy, Communications Manager for the AHA; and Katharina Matro and Shannon Bontrager, who both advised on the structure and format of the guides.

Finally, thank you to this discussion guide’s principal author: Thayme H. Watson