If it’s late July, you’ll find me at the Falcon Ridge Folk Festival, a multi-day immersion class in the art form of telling tales, preserving heritage and calling for change through music. (And rain.)

For as long as you can stay awake, you can hear music old and new, played by amateurs and professionals of all ages and levels of fame. On the official stages during the day, in the campsites and various other spots at night, you never know which combinations of musicians you might hear trying to outplay a thunderstorm. (Did I mention the rain? It’s really not Falcon Ridge until it rains.)

This year, it struck me that the festival is also a haven for the First Amendment.

If you’ve got a “Freak Flag,” as the great Greg Brown sings, Falcon Ridge is the place to let it fly. You can wear what you like, be who you are and say what you want to say–though please not during the music.

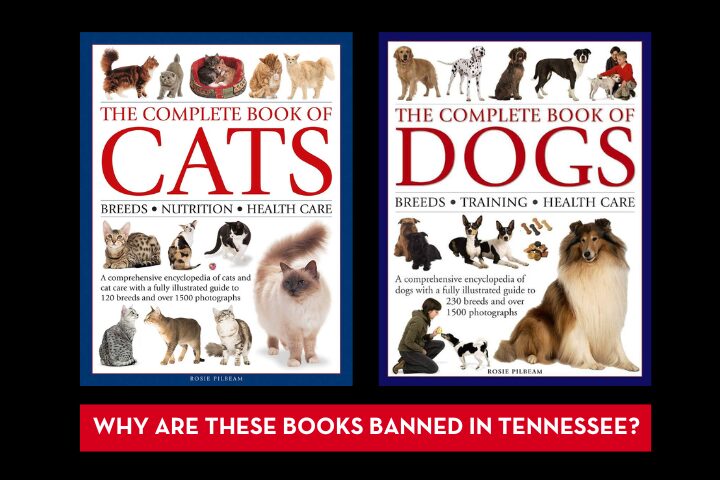

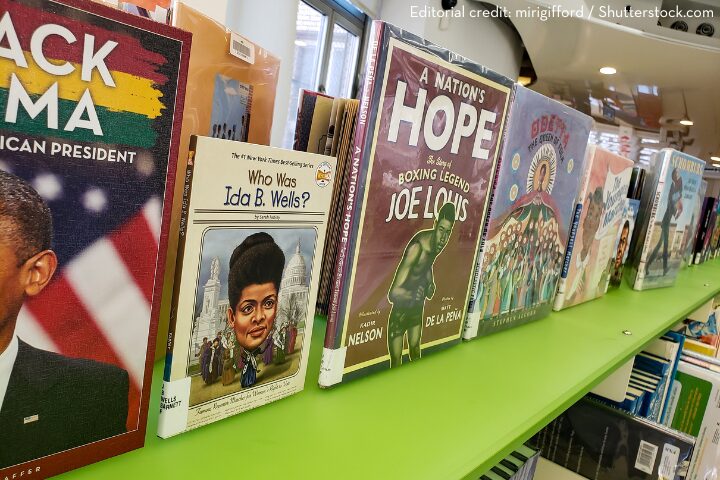

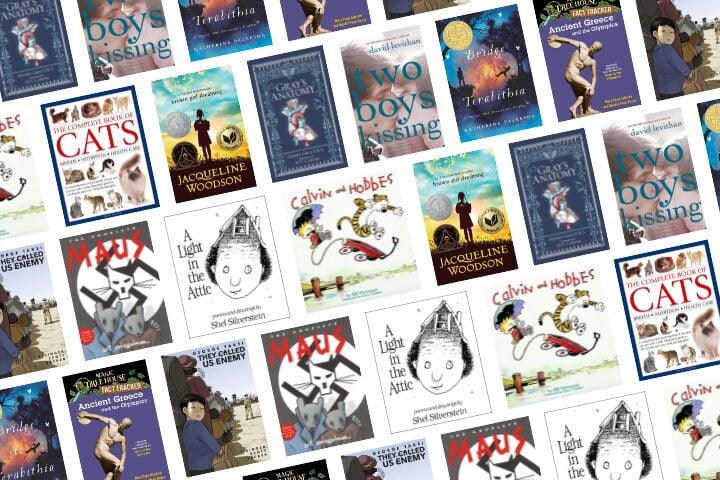

All around the grounds were people with t-shirts, hats, buttons, signs and flags expressing their views. While admittedly mostly liberal–it is a folk festival, after all–there was diversity to the topics and stances, both national and local. And many were simply pro-First Amendment – calling for a better, stronger media, criticizing book bans, and often just encouraging people to stand up for what they believe.

In that context, the story that balladeer Joe Jencks told the audience about his friend Pete Seeger was all the more appropriate.

Seeger, who died in 2014 at age 94, remains an icon of the folk music scene, getting references seemingly every time a performer encourages the audience to sing along.

But Jencks told about Seeger’s testimony 70 years ago before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), when he chanced his freedom by refusing to answer questions about his political activities and the people he met and worked with. After years of being blacklisted–his group The Weavers was at the top of the charts when they started losing bookings because of their “Communist” associations–and knowing he could face jail time, Seeger insisted not on the protection of the Fifth Amendment, or refusing to incriminate himself, as many others dragged before the HUAC did. Instead, Seeger relied on the protection of the First Amendment to make his case when he testified on Aug.18,1955, in the waning days of the “Red Scare.”

“I am not going to answer any questions as to my association, my philosophical or religious beliefs or my political beliefs, or how I voted in any election or any of these private affairs,” Seeger told the committee that had ruined the careers of numerous artists it grilled before him. “I think these are very improper questions for any American to be asked, especially under such compulsion as this.”

He repeated this statement multiple times, and even offered to play his banjo for the committee so that they could understand his music. “My songs seem to cut across and find perhaps a unifying thing, basic humanity, and that is why I would love to be able to tell you about these songs, because I feel that you would agree with me more, sir.”

Seeger remained respectful as he was asked over and over again to name names. But he continued to refuse to single out any individuals who performed with him or heard him sing for the congressmen seeking to point fingers at more people. “I decline to discuss, under compulsion, where I have sung, and who has sung my songs, that I have helped to write as well as to sing them, and who else has sung with me, and the people I have known.”

Seeger was cited for contempt of Congress in March 1957. He was convicted in a jury trial four years later, and sentenced to 10 one-year terms in prison, to be served concurrently. In May 1962, an appeals court overturned his conviction. But even at the risk of years of legal fights and potential jail time, with his career in limbo, Seeger stuck to his principles.

“I love my country very dearly and I greatly resent this implication that because some of the places that I have sung and some of the people that I have known, and some of my opinions, whether they are religious or philosophical, or I might be a vegetarian, making me any less of an American,” he testified. “I will tell you about my songs, but I am not interested in telling you who wrote them and I will tell you about my songs, and I am not interested in who listened to them.”

“I have sung to many audiences,” Seeger told the HUAC. “I have sung in hobo jungles and I’ve sung for the Rockefellers. I’ve never refused to sing for anybody. That’s the only answer I can give. I’m proud I’ve sung for Americans of every political persuasion.”

Today, we aren’t seeing activists, actors, musical artists or other U.S. citizens dragged before tribunals demanding they prove their loyalty to America, the way they were in the 1940s and ‘50s, though many have seen grants rescinded and other threats to their livelihoods. But if the government isn’t yet using its power to destroy citizen’s lives, the same cannot be said for legal U.S. residents who speak out. In addition, we are certainly witnessing U.S. officials and likeminded “influencers” attempting to inhibit opposition through social media. One viral example is the attacks lobbed at Seeger’s friend, Bruce Springsteen, over his comments during his concerts.

The Boss continues his world tour undeterred. But for people without millions of fans and vast wealth, this climate can feel frightening, making it difficult to stand alone, to disagree, or even to take part in some pretty old-fashioned forms of protest. Which may be just what this leadership wants—intimidation and silence.

Seeger, whose banjo bore the inscription, “This machine surrounds hate and forces it to surrender,” never regretted his refusal to buckle to HUAC. “Historically, I believe I was correct in refusing to answer their questions,” he said years later. “Down through the centuries, this trick has been tried by various establishments throughout the world. They force people to get involved in the kind of examination that has only one aim, and that is to stamp out dissent.”