The GOP’s victory in the November 2024 election will have major implications for academic freedom, free speech, and university autonomy in American higher education. Colleges and universities are entering an extraordinarily difficult period, as many recent proposals aimed at restricting ideas on campus are now more likely to become law or policy.

But some of the levers of change in the federal government are easier to pull than others. Given the closely-divided Congress, efforts to attack or undermine academic freedom that do not require legislation are more likely to go into effect quickly, as are attacks not vulnerable to court challenges. We can also look to actions taken by the federal government during the first Trump administration, or that have been promoted by Trump or his allies in the four years since (e.g. the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025), as an indication of what educators should expect.

Here’s what could be on the horizon for higher ed censorship at the federal level in 2025.

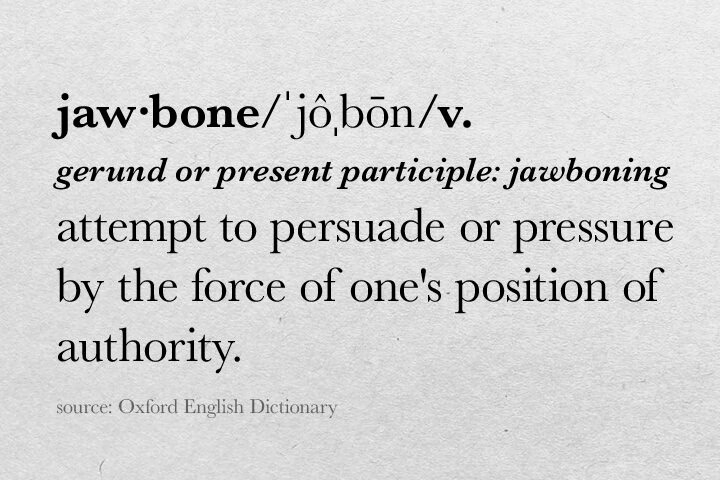

Jawboning and Congressional Investigations

College and university leaders have already been under immense pressure from Congress. Expect it to get worse. Congressional Republicans will no doubt interpret their electoral victory as a mandate to further investigate and harangue universities for their DEI policies, outspoken faculty, and responses to student protests. The House Committee on Education and the Workforce has already used this tactic to devastating effect, helping to bring down the presidents of the University of Pennsylvania, Columbia, and Harvard.

Indeed, the first and most immediate weapon that the federal government will likely deploy against colleges and universities will likely be jawboning – attempts to force institutions to censor themselves via intimidation and threats. Don’t expect Congress to pass sweeping laws that restrict expression on campus, at least not right away. They don’t have to. Rather, congressional committees can use their bully pulpits and subpoena powers to investigate and isolate individual universities, much as their counterparts have already done at the state level.

For private higher ed institutions worried they might be next in the hot seat, these actions will have a broad chilling effect on what ideas, decisions, and offices they feel able to maintain and support. For public universities, the threat is more direct: state governments, which control their appropriations and tend to have more direct authority over presidents, boards of governors, and so forth, will step in to finish the job. It will be a kind of call-and-response: federal politicians demand action, state politicians deliver.

Antisemitism Legislation and Title VI Enforcement

We also expect major changes at the Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights (OCR). This is the office charged with ensuring that all colleges and universities that receive federal funds, both public and private, comply with federal anti-discrimination law. An institution found to be in breach can lose access to these funds, a catastrophic (and in more than half of cases, fatal) blow to the institution. Matters rarely reach that point, however, as the targeted institution typically enters into some sort of remedial settlement with the OCR before the investigation’s conclusion. And as numerous examples from the last few years demonstrate, these settlements can be deeply threatening to open and free inquiry on campus. (The wholesale transfer of OCR to the Department of Justice, proposed in Project 2025, would likely have little impact on this threat.)

For instance, during the past year alone, organizations like the Brandeis Center, a pro-Israel legal activist group, have filed numerous complaints with OCR alleging rampant antisemitism in higher education. Many of these complaints rely on the IHRA definition of antisemitism and cite as evidence speech that, while critical of Israel or Zionism, falls well within the scope of academic freedom and free speech. Some universities have fought these charges, but many others have entered into questionable settlements with OCR that at times threaten to restrict basic political speech of students and faculty.

We can expect many more complaints along these lines going forward – and that whomever the Trump administration appoints to lead OCR will be sympathetic to them, perhaps even at the expense of the First Amendment.

There’s more. OCR is also the subject of the one piece of relevant legislation likely to pass quickly in the new Congress: HR 6090, better known as the Antisemitism Awareness Act. If passed – and, given previous support from Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and other Democrats, passage seems likely – this bill would formally direct OCR to take into consideration the IHRA definition of antisemitism in its work. The significance of this step may not be immediately apparent, since OCR has been making use of the IHRA definition for over a decade. However, it only does so currently at the direction of the Secretary of Education, and a future administration could reverse course. The Antisemitism Awareness Act would make adoption of the definition permanent, something that PEN America and numerous free speech groups believe would imperil the freedom of students and educators to criticize Israel or its government.

Relatedly, Trump will have the authority under existing legislation to move against international students and faculty who engage in certain kinds of anti-Israel speech. Per federal law, the Secretary of State may deny or revoke an individual’s visa if that person “endorses or espouses terrorist activity or persuades others to endorse or espouse terrorist activity or support a terrorist organization.” Shortly after Hamas’s attack on Israel in October 2023, Florida Senator Marco Rubio called on the State Department to wield this provision against campus protesters with a work or study visa who express their support for an “intifada” against Israel.

In the new administration, Rubio himself has been nominated to lead the State Department. State legislation with a similar approach was introduced in Florida and Indiana in 2024 (though these bills failed to advance), and it is one of the priorities outlined in Project Esther, another blueprint produced by the Heritage Foundation that outlines how a Republican president might combat what it terms the “Hamas Support Network.” Once he is sworn into office, Trump will have the opportunity to put these proposals into action.

DEI Bans and Federal Research Funding

It is also very likely that President Trump will resurrect, refresh, and expand his Executive Order 13950, “Race and Sex Stereotyping,” which he issued during the waning days of his first term. This is the executive order that triggered the anti-critical race theory movement of 2021 and 2022, resulting in a wave of educational gag orders passed in state governments and local school boards across the country. One of President Biden’s first moves upon taking office in 2021 was to revoke this executive order; Trump may move with similar speed to restore it. An expanded version of this executive order could prohibit DEI programming, “CRT” (represented by the nine so-called “divisive concepts”), and training or pedagogy related to LGBTQ+ identities in federal agencies, including military service academies.

Trump will also have an opportunity to change the criteria that federal funding bodies use to determine eligibility for grants. For instance, the National Science Foundation, which currently requires applicants for many research grants to submit diversity statements demonstrating their institution’s commitment to DEI, might, in an about-face, instead be directed to deny research funds to institutions for their DEI efforts, or to deny support for research projects whose topics or methodologies that have previously been targets of censorship. Texas Sen. Ted Cruz has already made recommendations to this effect, and the new administration will most likely take them seriously.

Neither of these changes require Congressional support; both can likely be implemented via executive action, meaning that Trump can order them on day one. By contrast, with the exception of the Antisemitism Awareness Act, passing a federal law that restricts academic teaching and research would be much more difficult – but not impossible. An example would be a national educational gag order, something along the lines of 2023’s HB 570. This bill, dubbed by its sponsor Rep. Chip Roy (R-TX) the “Combating Racial Teaching in School Act,” or the “CRT Act,” would deny federal funds to any college or university that “promotes” certain ideas related to race, color, or national origin. In other words, it is a federal “divisive concepts” bill.

A bill like this is unlikely to pass even a GOP-controlled Congress. Unless attached to budget reconciliation – which would require approval from the Senate parliamentarian – it would be subject to, and unlikely to overcome, a filibuster. Were it to become law, it would be immediately challenged in the courts on First Amendment grounds. Nevertheless, legislation like this will be part of the conversation going forward and may pave the way for something more feasible and only marginally less extreme.

A similarly challenging, but perhaps more plausible, candidate for passage is a bill along the lines of HB 7725, known as the EDUCATE Act. This bill, which was proposed in March 2024 but stalled in the House Committee on Education and the Workforce, would amend the Higher Education Act of 1965 to prohibit medical schools from establishing or maintaining a DEI office. It would also forbid them from requiring or incentivizing students or faculty to submit DEI statements or endorse certain “DEI concepts”. Universities, including private ones, that fail to comply with these prohibitions would lose access to vital federal funds. Because they receive large research appropriations from the federal government, medical schools are especially susceptible to this sort of threat at the federal level.

Weaponizing Accreditation

Also possible is a significant change to the accreditation system. Under the Higher Education Act of 1965, a college or university that wishes to receive federal money must be accredited by one of seven federally recognized accrediting agencies. These are private nonprofit organizations that monitor educational institutions for financial health, graduation rates, and academic quality. They also seek to determine whether universities protect the academic freedom of faculty or offer support for diversity goals.

Without federal student financial aid, universities cannot function. This gives accreditation bodies enormous power over the nation’s higher education system..

This is the power that Trump and his Congressional allies promise to take for themselves. Describing it as his “secret weapon,” Trump has said he will “fire the radical Left accreditors that have allowed our colleges to become dominated by Marxist Maniacs and lunatics,” and will replace them with accreditors that defend “the American tradition and Western civilization.” House Majority Leader Steve Scalise (R-GA) has offered a related proposal, vowing to strip accreditation from any college or university that fails to crack down on anti-Israel protests.

Steps of this magnitude are relatively unlikely. That’s partly because the negotiated rulemaking process in the Department of Education, unchangeable without an act of Congress, may make this sort of change functionally impossible. Changes of this type would also be extremely controversial and would trigger significant resistance.

Nevertheless, it is possible that lawmakers will move to restrict the role of regional higher education accreditors. At a minimum, they will likely pursue efforts to ban accreditors from having or enforcing DEI standards, a restriction called for in Project 2025 and one that may not require legislative changes in order to take effect.

Resisting the Threats

The higher ed sector is not helpless. College and university leaders have the capacity to defend themselves, their students, and their faculty against many of these threats. However, doing so will require enormous effort, political savvy, and a willingness to put internal differences aside.

Below are some recommended approaches for colleges and universities to resist these and other forthcoming threats.

- Defend academic freedom consistently. Colleges and universities should avoid making themselves easy targets. The best way to do that is to defend the academic freedom of all students and all faculty, regardless of ideology or partisan sympathies. Respecting academic freedom isn’t just good in and of itself – it is also the only way that university leaders can credibly defend themselves when they come under fire. When universities cancel lectures, disinvite scholars, or discipline faculty for protected speech, it becomes more difficult for them to shield themselves behind the principle of academic freedom when the government comes calling.

Going forward, university leaders should forcefully and unequivocally defend academic freedom and free speech. That means standing up to would-be censors wherever they arise, whether in the halls of Congress, the student body, the faculty lounge, or the broader community. Universities must also do a better job of educating their students and faculty about the limits of academic freedom and free speech – ensuring they know what sorts of activities are unprotected and for which they can be punished. Explaining these limits is neither easy nor uncontroversial, but it is necessary.

- Speak with care. To avoid being a target, university leaders must carefully weigh the pros and cons of speaking out on issues that can spur controversy. Yes, they must always be prepared to defend their values and speak out on their community’s behalf, especially when telling lawmakers not to police ideas on campus. Of course, individual students and faculty members have the freedom – and indeed the obligation – to speak out on the things that matter to them. But university leadership and other governing bodies (e.g. faculty senates, academic departments) should exercise prudence and lay out clear, careful principles to guide when they speak.

- Unify. If ever there were a reason for all members of the university community to come together, this is it. The external threat is enormous, and so the internal defense must be as well. University leaders who capitulate to political pressure will find that they’ve earned little goodwill from their critics and lost much from their supporters. Similarly, students and faculty should appreciate the political realities with which institutional leaders must contend. Before demanding that their university take some action or issue some statement, they must seriously consider whether the potential benefit is worth the likely cost. And ultimately, all campus stakeholders should recognize that the external threat to higher education on the horizon is so grave and overwhelming that any internal differences pale in comparison.

- Organize. But unifying is not enough. Students and faculty must also organize. One option is unionization, which has increased dramatically among both faculty and graduate students in recent years. Collective agreements should be written to enshrine academic freedom and guarantee due process to members under fire. And where unionization is impossible (and a Trump administration will likely do what it can to see that it is), faculty should consider connecting with PEN America, starting an AAUP chapter, contacting their disciplinary association, or engaging with groups like the Academic Freedom Alliance, the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, and Heterodox Academy. Similarly, university administrators should work through their professional associations to build power in numbers.

- Follow the law, but do not exceed it. Too often, colleges and universities go beyond what the law demands. This is especially common in states like Texas, Florida, and Utah where aggressive lawmakers are skilled at jawboning university leaders behind closed doors. For instance, even though Alabama’s new anti-DEI law does not ban most elements of a DEI office, campuses up and down the Yellowhammer State have been shutting these offices down in hopes of pre-empting further intervention by lawmakers. This defeatist attitude must be rejected. Universities must follow the law, but they should not volunteer to do the censors’ work for them.

- Don’t just serve students. Serve the community. The 2024 election revealed that the diploma divide has grown into a yawning chasm. The minority of Americans with college degrees now overwhelmingly vote for the Democratic Party, while the majority who lack a degree strongly favor the GOP. Addressing this disparity must be a priority for colleges and universities going forward. Higher education will not survive if it is seen as only benefiting members of one political party. Unfortunately, education polarization is a global trend that now appears in virtually every wealthy democracy, and so it will be immensely hard to reverse. Nevertheless, universities have a democratic obligation to try to change these dynamics, and they can pursue alternative strategies to the challenge as well.

The most promising of these strategies is to make themselves indispensable to non-students in their community. Just because a person is not and perhaps never will be a student does not mean that a university can afford to ignore them. On the contrary, the need to serve non-students has never been more acute. This can take many forms: hosting more public events on and off campus, providing free job training and professional workshops, altering tenure requirements to emphasize community service, and more. Nor can this outreach afford to cater only to those in the immediate vicinity of the campus. Geographic sorting in America is such that those living near universities are already predisposed to support them. That’s why faculty and administrators will have to venture further afield, going into communities where support for higher education has cratered.

It’s also worth noting that community colleges, technical and trade schools, and regional four-year public universities are now much more popular than other types of postsecondary institutions. Higher education as a whole can benefit from considering what role these institutions can play in helping to lead the defense of the sector.

The next four years will be very hard for higher education. Academic freedom, campus free speech, and university autonomy will come under enormous strain, all while colleges and universities struggle with mounting fiscal and demographic challenges. To survive, they must be willing to adapt – and to defend themselves. American higher ed’s brightest days can still be ahead of it, but it will have to fight for them.