When Andy Passchier heard the word nonbinary for the first time, they recognized almost instantly that it applied to them.

“I had spent 22 years feeling vaguely out of place, not quite right, uncomfortable in my skin and with how people perceived me, but I simply didn’t know that there were other ways I could be existing,” Passchier said. “Learning the word nonbinary was like opening a window and letting fresh air into a stale room for the first time, and I was able to begin truly exploring my identity.”

Passchier has always wondered what their life would have looked like if they were exposed to a more capacious understanding of gender earlier. Through the books they write and illustrate, like Gender Identity: For Kids and They, She, and He: Words for You and Me, they’ve strived to make that a possibility for kids today.

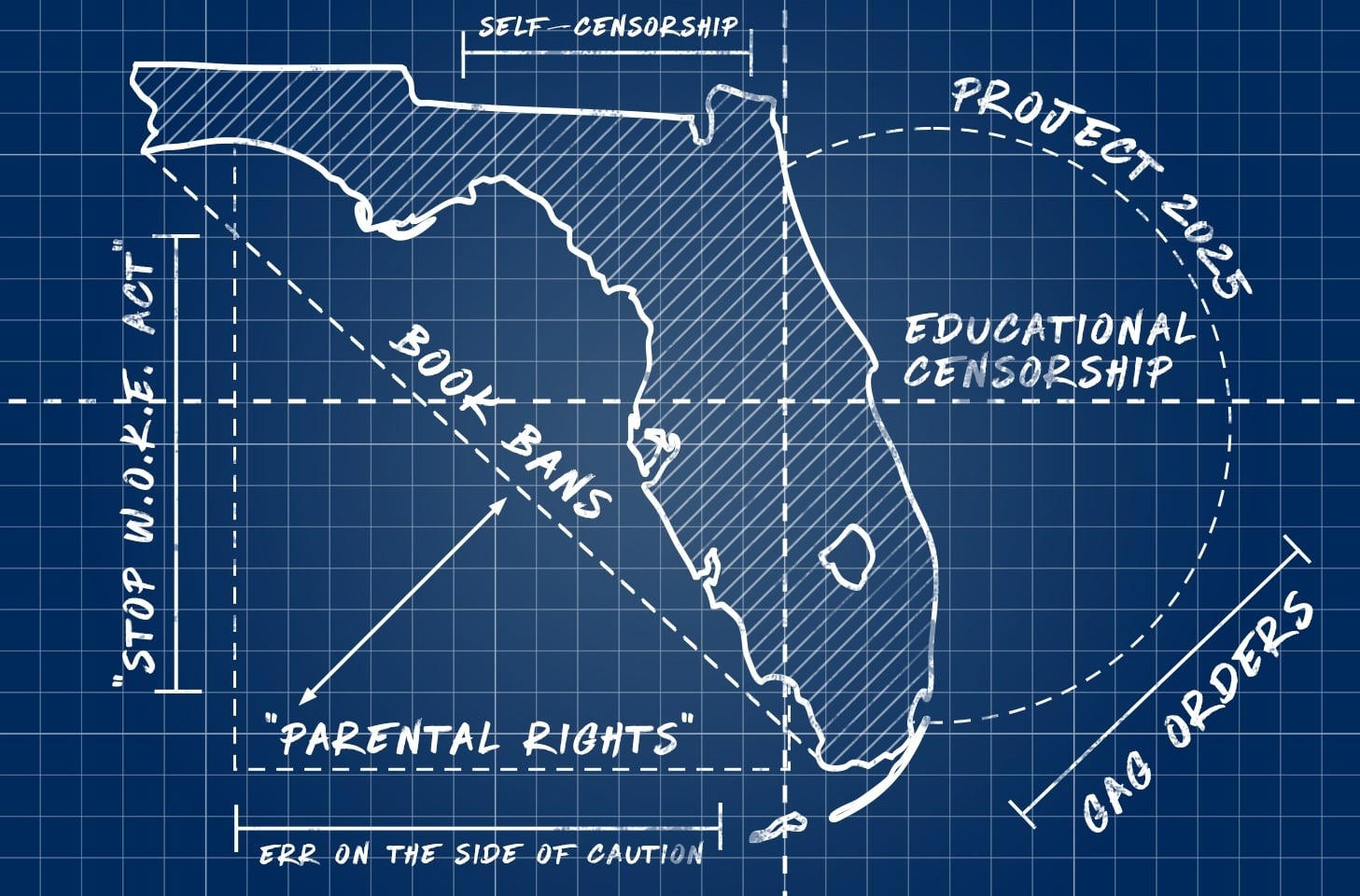

But book bans have thrown a wrench in that plan, much to Passchier’s dismay. “People always insinuate [being banned] is something I should be taking pride in or wearing like a badge of honor,” they said. “There’s nothing fun or prideful about it, and it affects every part of your life. It’s not an experience I would recommend or wish upon anyone else.”

As part of its legal work challenging book bans, PEN America recently interviewed authors about the toll of literary censorship. In addition to taking a hit financially, many reported feeling heartbroken and tired. They’re sick of having their identities attacked, and they’re devastated by the knowledge that young readers are being deprived of the opportunity to fall in love with their books.

“It’s a terrible, terrible experience,” said Kyle Lukoff, a children’s book author with five banned titles, including If You’re a Kid Like Gavin: The True Story of a Young Trans Activist. He feels helpless all of the time — and when librarians and teachers who attempt to stand up for his books face backlash for doing so, he can’t help but feel guilty.

People always insinuate [being banned] is something I should be taking pride in or wearing like a badge of honor. There’s nothing fun or prideful about it, and it affects every part of your life. It’s not an experience I would recommend or wish upon anyone else.

Robin Stevenson, the author of more than 30 picture, middle-grade, chapter, and young adult books, said that she’s deeply affected by bans because many of her books feature characters whose identities reflect her own. Over time, she’s grown more and more infuriated with book banners sexualizing and demonizing her LGBTQ+ protagonists.

“A story about a family with two moms is no more sexual than a similar story about a family that includes a mom and a dad,” she said. “It’s exhausting to face the same battles over and over again, upsetting to receive hateful messages from strangers, and incredibly frustrating and disheartening to see so much hard won progress being erased.”

Charlotte Sullivan Wild, author of the banned picture book Love, Violet, emphasized that diverse stories spiked in popularity only recently — so many weren’t on shelves for very long before they started to be pulled back down.

“I spent nearly two decades in the classroom and longer as an aspiring author pounding against the doors closed to stories about minorities,” Sullivan Wild said. “The public has only just jumped on board with celebrating inclusive books and truly supporting them with dollars and library checkouts. To have those same books and identities threatened again, and so quickly, is disturbing. I am worried for our democracy. I worry for our children. I worry for every person whose identity is being censored.”

Author, illustrator, and cartoonist Rachel Elliott said that having her book challenged has taken an unexpected toll on her mental health. She wished it felt like receiving a less-than-stellar review, but it’s been incomparably worse.

“Someone out there wants your several years’ worth of work erased from the earth,” she said. “It’s like there’s a real-life, movie-sized villain that’s taking your hometown librarian hostage and saying, ‘I’ll put her in jail because of her book!’ It’s spooky and disorienting.” Sometimes, Elliot added, she finds herself so disoriented that she has to check in with family members or friends to confirm she’s not imagining any of the attacks on her work.

For authors Sarah and Ian Hoffman, it has been especially difficult to accept that when their books are removed from library shelves, underserved kids — whose parents don’t have the time or resources to acquire the books they need — lose out the most. The Hoffmans have written the books Jacob’s New Dress, Jacob’s School Play: Starring He, She, and They!, Jacob’s Room to Choose, and Jacob’s Missing Book all with the purpose of introducing kids to the concepts of gender and gender expression.

Sullivan Wild said she shares the same concern. “Libraries provide free access to books and information, something that helps to reduce disparities between economic classes, especially for children,” she said. “Free access to information and books isn’t supposed to be only be for the most rich.”

“I’m emotionally exhausted,” she added. “I would rather spend this energy writing whatever book I think would delight, engage, comfort, and challenge children.”