Students were already waiting in the library at Country Club Elementary School in San Ramon, California, when children’s book authors Joanna Ho and Caroline Kusin-Pritchard arrived in late October to talk about their book, The Day the Books Disappeared.

But first, the authors got sent to the principal’s office.

The authors had prepared to share their story about a boy named Arnold who discovers he can make books disappear and gets carried away with his abilities. But the principal informed them that they were not permitted to address the topic of the book – book bans – in their talk.

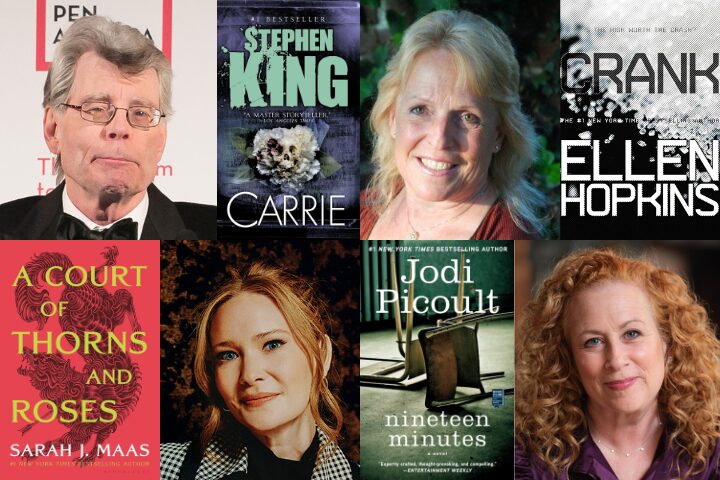

In fact, the principal demanded they remove seven of the 45 slides in their presentation that addressed book bans and the types of books that are banned, including five slides featuring material from PEN America illustrating how many books have been banned across the country and the kinds of books that schools often remove from student access. Specifically, they were ordered not to mention LGBTQ+-authored or queer-centered stories.

In an Instagram post, the authors said the principal told them the directives came “from above.”

“We responded that this would be out of our integrity and we would not change the presentation,” Caroline Pritchard said in the posted video.

In sum: The event was cancelled over concerns the presentation on school book bans was “not suited” for younger students. It’s part of a growing list of efforts to censor the very subject of censorship.

A few weeks later and more than 2,400 miles away, the topic of book banning was also deemed not suitable for older students. In Cobb County, Georgia, students participating in the state’s Helen Ruffian Reading Bowl discovered their choices of books in the competition were narrowed when eight of the 20 titles were removed from the high school reading list.

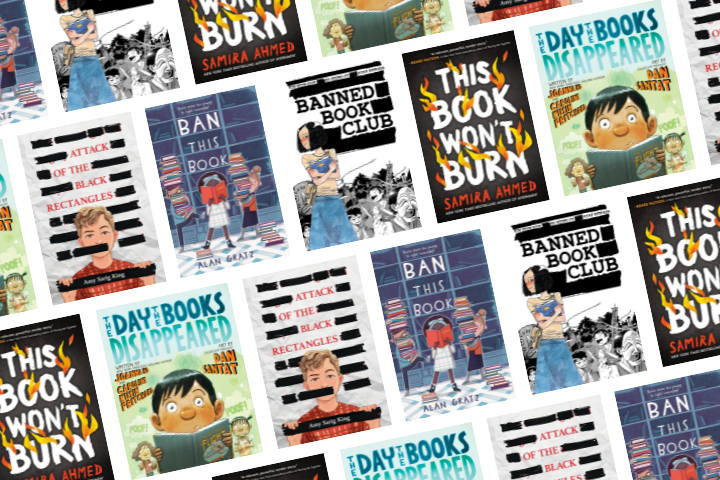

Among them, This Book Won’t Burn by Samira Ahmed, which tells the story of Noor Khan, who is moved to action when she discovers that thanks to a new school board policy, hundreds of books written by queer and BIPOC authors have been labeled “obscene” or “pornographic” and are being removed from the library at her new high school. In response, Noor and other students form a “banned camp,” where they get together to read banned books.

Cobb County high schoolers, along with parents and educators, were spurred to respond like Noor did when they learned about the limits to their choices, and the outcry led to the books being restored for students in the competition.

It wasn’t even the first time Cobb County ran into trouble with books about censorship in the competition. Two years ago, media specialists and teachers who volunteered for the Reading Bowl backed away from the competition over fear they might get in trouble for making “inappropriate materials” available to students, including Amy Sarig King’s book Attack of the Black Rectangles, which is about book censorship of sexual materials.

From a rising number of author talks canceled or restricted, to books pulled from school library shelves — like the children’s novel Ban This Book by Alan Gratz and the graphic novel Banned Book Club by Kim Hyun Sook and Ryan Estrada – the subject of censorship appears to have joined the list of taboo topics. Classics on the topic have been hit too, like Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 and Markus Zusak’s The Book Thief.

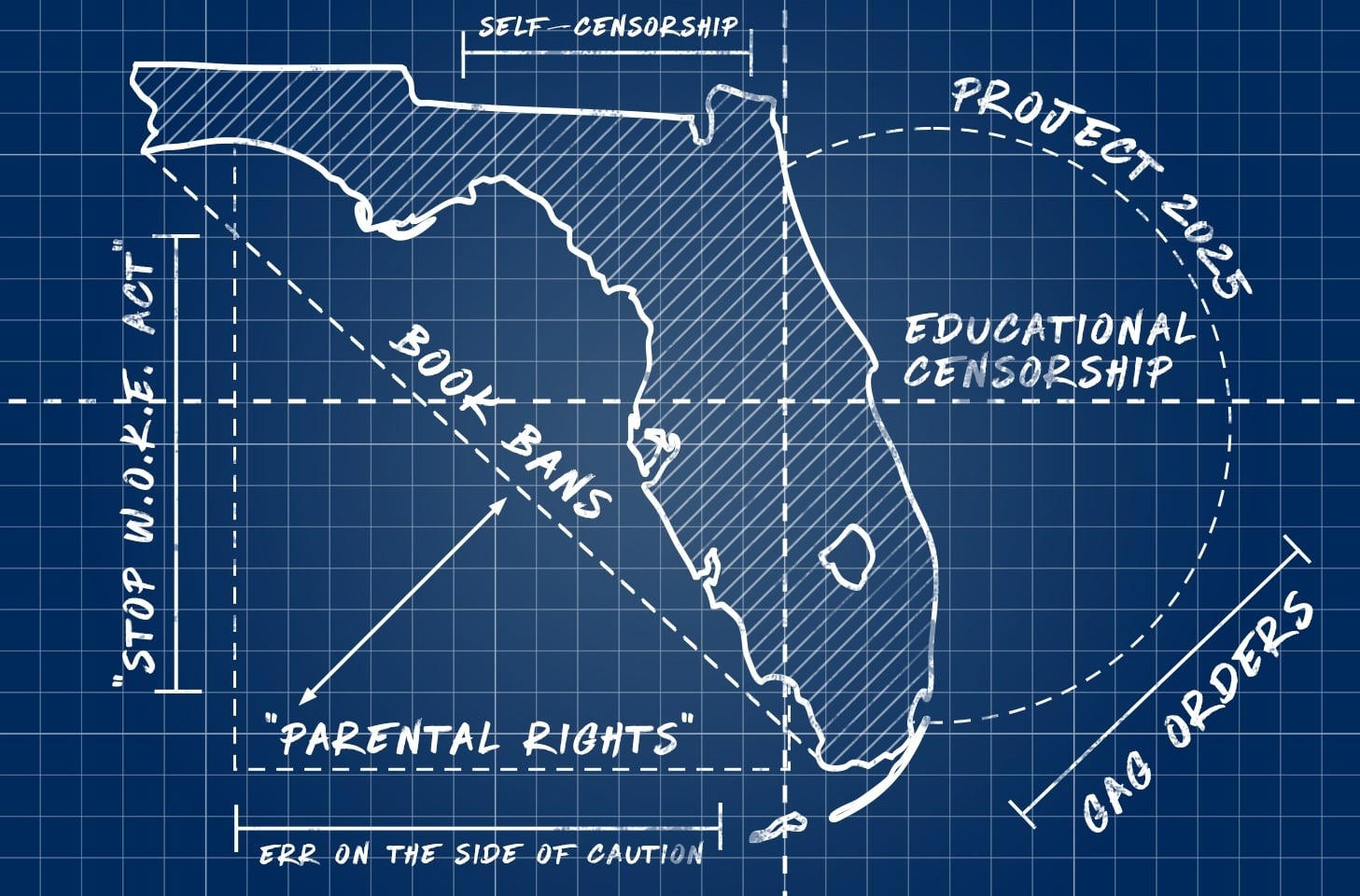

It’s no coincidence that this is happening as book banning has become normalized in the U.S., with at least 21,810 documented cases since 2021; while the Trump administration has deemed an ever-expanding list of words unacceptable for use by the federal government, and while states have passed laws banning diversity, equity and inclusion efforts of all kinds. Laws are increasingly being interpreted as prohibiting even discussion of the censorship they’re causing.

In one of the more absurd examples, organizers at Utah’s Weber State University last semester canceled a planned two-day conference called “Redacted: Navigating the Complexities of Censorship,” after the school’s administration attempted to restrict the scope of the discussions, citing the recently implemented state law, HB 261, which bans DEI programming, along with any programs, activities, and trainings that endorse a specific list of concepts that relate to identity.

There’s irony in banning discussion about censorship or a book about book bans, but it’s hard to find the humor in what appears to be an increasing trend of censoring the very discussion of censorship.

And it’s happening throughout the country. The Hawaiʻi State Public Library System, for instance, actually banned Banned Books Week this year. The system issued new guidelines before the 41st annual event that prohibited the use of the words “censorship” and “banned,” as well as the phrase “Banned Books Week,” in displays at 51 public libraries across the state. They mandated that libraries use the phrase “Freedom to Read,” without providing context about the meaning behind the words.

Even more concerning are moves to suppress the discussion of censorship in order to avoid provoking the wrong people.

In Washington State, for instance, workers at one public library were instructed to refrain from using the phrase “banned books” in displays in order to “keep things positive,” Book Riot’s Kelly Jensen reported. They were also instructed not to display any books that might “poke the bear.”

It all amounts to an increasingly Kafkaesque situation, where reading and talking about book bans and censorship is itself being censored. Considering the rate at which censorship is emanating from state and federal governments, it’s all the more important that citizens stand up for free speech, before censorship is censored any further.