This Q&A is part of a series that will include interviews with journalists and experts who regularly handle disinformation. The interviews will appear regularly through the election and beyond to highlight best practices, insights, case studies and tips. Our goal is to provide a resource to assist reporters and community members through the news events of 2024.

When Joseph Darius Jaafari and Jake Hylton founded LOOKOUT, they wanted to demonstrate a new way of telling LGBTQ+ stories through complex investigative journalism with community building at its center. In the two years since its founding, they’ve discovered the approach has slowed the spread of disinformation in Phoenix, where they are based.

For Jaafari and Hylton, LOOKOUT’s editor-in-chief and executive director, respectively, their focus on community journalism is occurring at a time when trust in media is declining, despite the increased need for responsible journalism. Their perspective comes amid troubling surges in disinformation about transgender people, drag queens, and the LGBTQ+ community, alongside a sharp rise in hate crimes, harassment, and attacks on LGBTQ+ expression.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

In recent years, we’ve seen disinformation campaigns escalate with an increasing focus on the LGBTQ+ community — particularly targeting the trans community. What worries you most about this trend?

Joseph Jaafari (he/him): What’s most alarming about this trend is the fact that there doesn’t seem to be any end to it. We’ve seen these kinds of attacks on the community before. This isn’t anything new. It’s a very tried and true method that has been seen decades before. What’s different about it this time is that it seems to have a lot more reach than it used to. A lot of that has to do with the proliferation of social media, fake news websites, pink slime websites, etc. — and that is the biggest hurdle when it comes to facts-based journalism trying to combat misinformation.

There’s so much out there that’s false, it’s almost impossible to debunk it all. On top of it, we’re now seeing that debunking actually doesn’t work as well as we thought it did. You need to pre-bunk. How do you actually do that in the realm of trying to teach people about something while also informing the community to take action, or be vigilant, or be resilient? It’s just become increasingly harder to combat that misinformation in the face of growing distrust of almost all media. At the same time, a growing number of media outlets [are attempting to fight back against misinformation].

Jake Hylton (he/him): I think that the disinformation is only one piece of it. The thing that worries me the most is that disinformation leads to violence. It’s not so much just the actual disinformation, but it’s the effects of that and the side effects of that in our society. That disinformation [about the LGBTQ+ community] really does lead to societal vitriol and violence against the queer community.

The hard part about it is that it becomes viral, and then it starts to infect other things, like legislation, the economy when it comes to local businesses, or healthcare providers. All of that is something that we have already seen before. But it’s the thing that scares me the most. Disinformation is so prevalent that now, it’s not only leading to violence, but now people are calling it truth.

There’s been a lot said about disinformation campaigns about the queer community, but less said about the spread of mis- and disinformation within the queer community. Do you think that’s an oversight? What do we get wrong when we talk about disinformation and the queer community?

JJ: We often assume that [disinformation within the community] is very small. It may vary between demographics as far as areas and regions. In Arizona, we do have a large amount of disinformation within the community, but that’s also because we have massive news deserts. When we initially did a lot of our research, we found that people were turning to social media in larger numbers than you would see in other large cities with large queer communities. That, in turn, leads to different bubbles, different kinds of facts that you might get from different sources. Some people leaving some things out, some people are hyperbolizing some events. All that stuff that happens within other communities, but because our community is so big here — we’re the 13th-largest LGBTQ+ population in the nation, fifth-largest city in the nation — by natural consequence of having these information deserts within our community, those tend to exacerbate the problem. So, yes, it’s often overlooked.

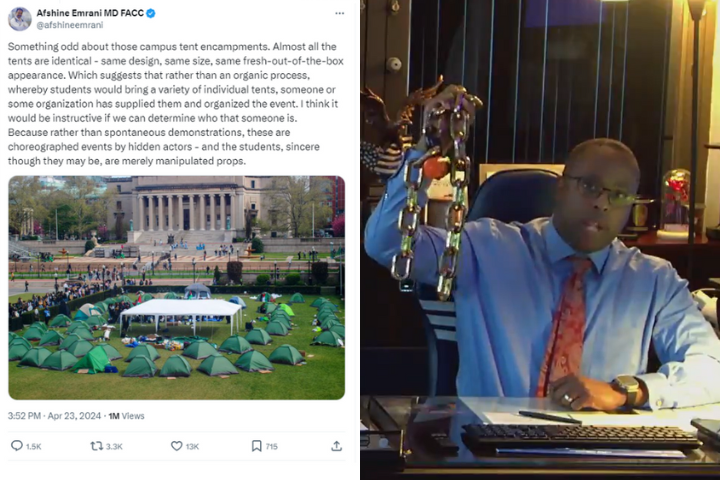

We have Gays Against Groomers, which spreads disinformation. We have the LGB Alliance, which spreads disinformation. We continue to have members of the Log Cabin Republicans spread disinformation. The disinformation being put out there is very organized [by those] that are doing something that they feel is the right thing to do, either maliciously or due to their naivete. It’s quite prevalent. (Officials with the Log Cabin Republicans and LGB Alliance did not respond to a request for comment.)

The reality is, that if we don’t address misinformation within our own community, then it’s just going to spread. That’s why LOOKOUT has said from the very beginning, we aren’t just holding people accountable outside the community; we need to do the same within. We need to hold the lens to ourselves in the same way we do to other people.

I’m wondering: How does the upcoming election, and the environment that the election is creating, complicate your work or make it more urgent? How are you feeling that impact in your community or in the people that you’re talking to?

JH: The mis- and disinformation that is going around is exhausting. We’re seeing a lot of the community wanting to disengage with the political sphere. I think that there is a lot of pain and a lot of anger. There’s a lot of fear amongst our community. But I think that a lot of [LGBTQ+ people] are really tired, because their entire life, they’ve had to fight just to be who they are. And now it’s happening not just on a familial, or a neighborhood, or a social scale in their own circles, but it is [now] happening on a state, regional, federal – in parts – global level. And so, what I’m seeing a lot is that people are keeping [news and the election] much farther away than it probably should be, just for their own well-being.

JJ: Obviously, we keep hearing about Project 2025 and Agenda47, which have LGBTQ+ discrimination clauses in them that [would] take away trans healthcare, reinstate the trans military ban, all those kinds of things. It’s very much being played out on the national stage, but I think often overlooked is how [the LGBTQ+ community is] being used in local — very, very local elections.

When we forecast our coverage of the election, of what needs to be kind of debunked, or prebunked, it’s really looking at school board races. It’s looking at the county attorney races. It’s looking at all these different judges that are taking the bench or trying to keep their seat on the bench. Because in each one of these elected positions, the people who are running in those positions have public platforms against the [LGBTQ+] community, and they are spouting the same false rhetoric about the “trans-ing” of children, how drag is sexualizing children, how certain books in public libraries or even schools are sexualizing children, how sex education shouldn’t be available because it sexualizes children.

It’s often overlooked because there’s just not enough local news reporters on the ground to debunk this — it’s all being said much louder on the local candidate stage. It’s a lot of people on the ballot across the state, in different districts, in different counties, in different regions, that it’s almost burdensome or onerous to try to name and shame them, or even just identify them. It’s really, really hard. It’s really prevalent. And I don’t think there is enough conversation on how this specific issue — LGBTQ+ people and the issues that they face, and the hatred they face — is a main platform for a lot of [local] candidates.

You both have touched on this, but from your perspective, Joseph, what role can local journalists and newsrooms play in defending their own communities against disinformation? Or, even further, what is the role that community building plays in that?

JJ: Both are so important, and I don’t think we’re even doing the best job at it [at LOOKOUT], because there is so much to be done. Because we are a niche news organization, our job is to identify problems within our community, attacks against our community, both in and out of the community, and basically, bring some kind of lens to the issues so people can understand the news side. And like I said earlier, there’s so much to debunk, there’s so much to cover, that we are like a small speck of sand in what needs to be a beach of news reporters and outlets covering these issues. We can’t do it alone, and thus, we only have a certain [number of] opportunities to affect people’s minds and hearts. The reality is that if news organizations cared about this issue enough, if they didn’t just treat the community as Pride parades and drag shows, and bills after they have been [proposed] and covering it from that angle, they [could] actually think of it as proactive beats, like they do the race beat, the identity beat, business, health. If they treated it the same way, then there is an opportunity to really dispel misinformation.

I feel like news organizations think of community-building as just informing the community early on. Coming from a traditional news background myself, I had always thought as well, we just want to give them the news and they can build their community. The reality is that when there is a dearth of opportunities to build community in an area, it is up to us as the community liaisons, the voice of these people to those in power or to others with access to levers of power; it is our opportunity and our responsibility to convene these people and create community.

I don’t think news organizations have been doing that too well, because they think by putting on a panel, that is somehow community-building. [Community-building] is doing things that community organizations are doing. It’s gathering people to see a movie together. It’s gathering people to do a dance-off or something — something to build each other up, while also informing each other about our differences and our similarities. And unfortunately, news is very late to this.

On that point about community-building, what role can community members play in serving as trusted messengers — combating disinformation narratives in their own networks, particularly when it comes to disinformation about the queer community?

JH: Not to sound like a TSA [Transportation Security Administration] announcement, but if you see something, say something. If you hear something, speak up. I think that we’ve been, as a society, conditioned to be like, “don’t ruffle feathers, don’t cause drama, don’t make friction.” And I think that now is the time to ruffle feathers and to cause friction.

For community members to be trusted messengers, it is first and foremost [important to] make sure that you educate yourself. Stay educated on fact-based information, and if you question something in that, do your research and look a little bit further. If you hear disinformation being spewed about, address it. It feels scary, and it also feels too simple, but I think that that is the best place for us to start.

My therapist once said to me — and I have never forgotten it — that if you can name it, you can tame it. She was talking about that in the realms of always calling out your abuser, because it’s important that other people also know about that abuse. And I feel like this is very much the same thing here. Disinformation is violent. One could say it leads to some sort of societal abuse; and if that is the case, then it is our place to call it out and make mention of it, to address it and say, “oh, that’s actually not right,” “oh, that’s not real,” “oh, drag queens don’t want to sexualize your children.”

For too long, especially over the last eight years, we have just said, “oh, I’ll let that go.” And now we’re seeing this snowball-effect. This thing that started off so small, as just somebody sharing some misinformation, has grown, and it has gotten into the hearts and minds of everyone. And so the best thing that we can do is call it out. If they’re never confronted about it, they’re just going to keep doing it.

JJ: I want to add to that. Jake said that disinformation is violence. That’s not hyperbole. Storytelling really embeds in a person’s being. So, if you are constantly being told that queer people are groomers, aka, they’re pedophiles; if you’re being told that a Pride parade is essentially sexualizing young kids to be gay or to do deviant things … You keep hearing that enough, you think about what four years of disinformation can do to somebody, and then all of a sudden, it’s ingrained in them. [They then feel the need] to do something to stop it. And that’s how we get attacks against the community. It doesn’t just happen in a vacuum. It’s not that somebody reads something online once, and then goes out and shoots up Pulse Nightclub. It’s years of disinformation, years of a narrative being sewed by people.

I just have one more question, and this is for both of you. We’ve talked a lot about fatigue, turmoil, and fear, but I would love to hear something that you have done in your work that has given you some sense of hope or optimism? What is something that you’ve done, that has worked and that you’ve been really proud of to keep pushing forward?

JH: I would say for me, it is meeting people where they’re at. A really big part of this, that we haven’t really talked about or mentioned, is that people do just want to be heard. I think that [the spread of] mis- and disinformation is a byproduct of wanting to be heard and wanting to be seen; which is why I actually feel like it’s probably really easy for the queer community to get involved and spread mis- or disinformation. And so for me, I’d say that the thing I’m really proud of that I will continue to do is to meet people where they’re at and to have those crucial conversations.

I regularly hear from our readers. I take it upon myself to make sure that I talk with them. And that means that maybe I spend five hours a week meeting with people who are just our readers, because they want to be heard. And that means giving them that space and that platform and having an intellectual conversation with them. I think that no matter what, it’s always going to be emotional, but if I am able to be there and not be on the defensive, then it allows me to A) better understand them and where they’re coming from, and B) they can understand where I’m coming from. They take one step out of their echo chamber, and that is the most important thing.

JJ: This is hard, because on the dis- and misinformation front, I don’t think we have anything to celebrate. I think we have a long way to go, and I don’t think the small impacts we’ve had are worthy of throwing up the “Mission Accomplished” flag. I do feel like the one thing that I give LOOKOUT credit for is understanding that there is a dearth of effective, qualifying, fact-based journalism for the community in Arizona. What is great about what we do is that, exactly how Jake goes in and listens to the community, we do the same thing for our editorial. We listen, we hear. We really try to get people into the fold to build something resilient that can last. And so, the goal is to branch out and make sure that we’re actively getting people who suffer from misinformation to get into the fold. I am happy that we have been able to do that, but we still have a long way to go to say we’ve executed on that.

Joseph Darius Jaafari is Editor-in-Chief at LOOKOUT. He has a background as an investigative reporter and editor, and has previously worked for the San Mateo Daily Journal and San Francisco’s 7×7 magazine.

Jake Hylton is LOOKOUT’s Executive Director. With a background in entrepreneurship, Hylton has previously worked with arts organizations, residential housing, and other community-focused industries.