Efforts to ban academic programs at universities for ideological reasons are spreading across state legislatures this year, but with a new rationale — “return on investment.” This buzzy phrase may sound like an effective way to cut costs or make higher education more efficient, but it is cover for an insidious form of censorship.

The “ROI” argument — recently surfaced in Iowa – has been made in state after state to target programs including gender studies. In a Texas hearing last year, legislators discussed the development of new bills based on Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick’s directive, “Stopping DEI to Strengthen the Texas Workforce,” which claims that diversity, equity, and inclusion policies are “damaging and not aligned with state workforce demands.” Florida announced that it will study the “return on investment” of women’s and gender studies programs and compare them to programs in computer science, finance, nursing, and civil engineering – likely as a precursor to eliminating the women’s and gender studies programs entirely.

In recent testimony before the Iowa House Higher Education Committee, Neetu Arnold of the conservative Manhattan Institute said Iowa’s public higher education institutions are in crisis, partly due to “runaway costs.” Despite Arnold’s own testimony showing administrative spending growing fast at several universities while “instructional expenditures” have, in some cases lagged, she recommends that universities cut costs by targeting academic programs that have a “negative return on investment (ROI).” For Arnold, an academic program has a “negative ROI” if a student’s additional income after graduation, net of the costs they paid to get that education, is lower than if they had not gone to college at all. Citing research from the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity, Arnold pointed to specific programs at public universities in Iowa that allegedly have negative ROI, including performing arts, social work, music, gender studies, and English.

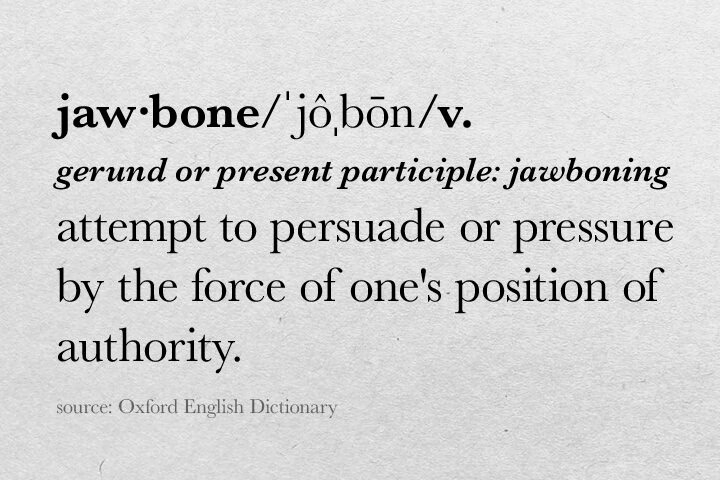

One can deduce Arnold’s reason for targeting these academic programs. Initially in her testimony, Arnold categorizes academic programs such as gender studies, social work, and theater as having “gotten into the weeds of politics” and having an “activist-bent.” She then goes on to say that these programs “tend to have a negative return on investment” and that programs with negative ROI often suffer from “ideological capture.” Arnold’s argument uses an economic rationale to impose ideological restrictions on academic programs. Cutting these programs may not be the most effective way to cut university costs but it does provide an avenue for cutting academic programs that might challenge the preferred ideological worldview of those in power.

Unfortunately, using “return on investment” or “workforce development” as a smokescreen for ideologically-motivated program bans is a tactic that has been adopted by state legislators. Iowa Rep. Taylor Collins and Sen. Lynn Evans sent a letter to the Board of Regents advising them to reject a proposed School of Social and Cultural Analysis at the University of Iowa on the grounds that institutions of higher education should “be focused on providing for the workforce needs of the state, not programs that are focused on peddling ideological agendas.” Since Arnold’s testimony, Collins’ House committee has proposed a slew of ideological restrictions on Iowa colleges and universities, including restrictions on general education and courses that include “DEI- or CRT-related content.” The targeting of courses that include “DEI or CRT-related content” can also be seen in model legislation proposed by the conservative Goldwater Institute.

Censoring academic programs for ideological reasons is obviously a threat to the free exchange of ideas on campus. But legislators should also understand the paternalistic implications of accepting Arnold’s argument. Targeting these academic programs on the grounds of ROI revokes students’ ability to choose what subject to study and what career to pursue and suggests that American students are not capable of making decisions for their own good. They should not be left to their own devices to choose to study English or theater, or to get a degree in social work (what student expects such a degree will make them rich?). They must be forced instead to choose a more practical field that results in what governing officials deem to be an acceptable ROI. The implication of these efforts is that the government should choose what kind of life students lead and what ideas they are exposed to.

The First Amendment protects the right to the freedom of speech, of religion, of the press, of movement, of assembly of all Americans against government censorship and suppression —freedom from tyranny. Legislators who value those freedoms should be wary of enacting government control over what kind of knowledge a university disseminates and what a student is allowed to choose to study. We should recognize these arguments about return on investment for what they are: paternalistic overreach at best, intentional political censorship at worst.