An Interview with PEN/Robert J. Dau Prize Winner: Seth Wang

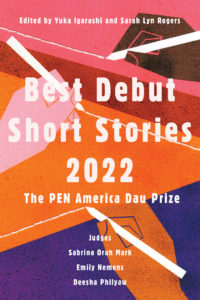

In the upcoming weeks, we will feature Q&As with the contributors to this year’s Best Debut Short Stories anthology published by Catapult. These stories were selected for the 2022 PEN/Robert J. Dau Short Story Prize for Emerging Writers by judges Sabrina Orah Mark, Emily Nemens, and Deesha Philyaw.

Seth Wang‘s (they/he) fiction has appeared in Ploughshares, Gulf Coast, and Passages North. They are a winner of the 2022 PEN/Robert J. Dau Short Story Prize for Emerging Writers and were a finalist for BOMB Magazine’s 2021 Fiction Contest. Seth has an MFA from Washington University in St. Louis (’22), where he is the Senior Fellow in Fiction. He is currently working on a novel.

“The Cacophobe” was originally published in Ploughshares.

Here is an excerpt:

I had no idea how much of it, if any, was true. But I didn’t care. I could listen to her without incurring so much as a hive. Even more than that, I relished the things she told me. Up until that point, I’d developed a sense of beauty purely by what hurt me the least. But, listening to Claude speak, I felt as though someone had drilled a hole in my skull and poured in molten discernment. For the first time in my life, I was enjoying beauty for beauty’s sake.

Why did you choose to make this an epistolary story? What was the process behind that?

The frame narrative is about a guy committing suicide, and it’s narrated in first-person. It’s probably more of a process not to make it a suicide note! I love the suicide note as a form because of its compressed intensity. A suicide note contains endless literary potential: it can be a last will and testament, final love letter, confessional, life story, the vow of revenge, rant, elegy, gorgeous magnum opus, all of that, and more. Everyone’s dirty secrets are coming out, the writer no longer cares about the social consequences of publishing its contents, and there’s also all this innate urgency to leave their mark, artistically or otherwise.

For this story, in particular, the form also allowed for some interactivity. One of my narrator’s symptoms is bleeding from his eyes, so as he’s recalling certain things that trigger him he’s constantly bleeding onto the page. That was fun for me to write.

What advice would you share with aspiring writers?

What I tell my students, is READ. There’s no shortcut or replacement. Also, SLOW DOWN. Literature should not be speed-read. There is no honor in being a “voracious” reader. Read out loud when you encounter good sentences. Copy out excerpts word-by-word. Annotate hideously.

One thing I don’t really see every time a certain discourse is re-litigated is advice on how to read better. So here are some practical tips from someone (me) with severe, diagnosed, unmedicated ADHD, among other disorders that make reading challenging. It obviously won’t work for everyone, but it really improved my life:

- Put on some modular, polyrhythmic, repetitive instrumentals. I like this one. The top comment is from someone who claims to be a neurobiologist and they explain why it works very convincingly.

- Have your quotations doc open in one tab.

- Have your ebook open in another (or a physical book in your lap). The Internet Archive’s interface is especially well-suited for this.

- Type out quotations you want to learn from as you read. The physical act of typing gives your mind and body a process to focus on, forces the words into a linear and logical flow so you’re less likely to bounce around or skim or glaze over, aids recall and comprehension, and internalizes the mechanics and structures of artful writing. I don’t know if there’s the scientific basis for any of that, but that’s how it works for me.

What do you hope readers take away from your story?

That they want to read more of my work! Like this story.

What inspired you to write this story? Where did the idea come from?

I’m not interested in the trauma plot. But I’m very interested in the way people use trauma and identity as an apologia for shitty behavior–especially my favs, cowardice and cruelty. The self-mythology required to live with yourself has always interested me enormously. A writing instructor of mine once complained that Hannibal Lecter getting a traumatic backstory undermined his effectiveness as a villain, but I think that only makes him an even better and more realistic villain. Like, it doesn’t get any more villainous than going “Nazis ate my sister so now I’m fully justified in making tapas out of the impolite.” Perfect. Delicious. No notes. Nabokov understood this, which is why the opening of Lolita works so well. My story is kind of a remixed condensation of that and Against Nature. It’s also very consciously in the tradition of whiny murderer-aesthete confessionals like John Banville’s The Book of Evidence, John Lanchester’s The Debt to Pleasure, and David Madsen’s Confessions of a Flesh-Eater. Just about everyone in my story fetishizes a particular incident in their past and performs extreme, increasingly ridiculous mental gymnastics trying to make it rationalize their sick little hobbies.

Closely related to that: The other primary interest of mine while writing this story was this growing tendency for people to pathologize everything, especially as a way to maintain the moral upper hand. My story takes place in a sanitarium for delinquent rich kids, and there’s a lot of bad psychoanalysis going on with regard to phobias and philias. Armchair psychology is literally built into the place’s modalities. I don’t want to reveal too much, but I wouldn’t take my narrator at face value for what he says about his condition. He claims he’s allergic to “ugliness,” and definitely reverse engineers this pathological justification for everything–from his (extremely limited, obviously biased) set of aesthetic preferences, to his environmental indifference, to his decision to lock himself away. But if you actually track what sets off his symptoms, that logic falls apart. It’s something else.

To be clear, I didn’t sit down with these themes in mind or set out to critique anything. I don’t write parables; this isn’t satire. There’s no perfect one-to-one to anything, and a lot of these ideas play out in an entangled, recursive way. I’m a character-first writer, most of all. Once I have the character and voice, everything else is just about calibration.

How has the Robert J. Dau Prize affected you?

It changed everything. I was at a very low point mental health-wise and seriously contemplating ditching fiction forever and just “quiet quitting” until my final MFA check came in when I got the email. The prize brought me access, representation, validation, financial support, career fast-tracking, and, most importantly, narcissistic supply. I am enormously lucky and grateful.