Panic about sex in books is on the rise.

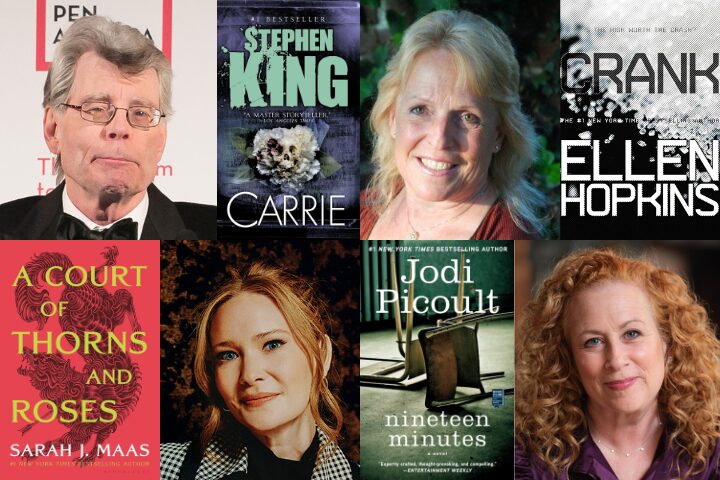

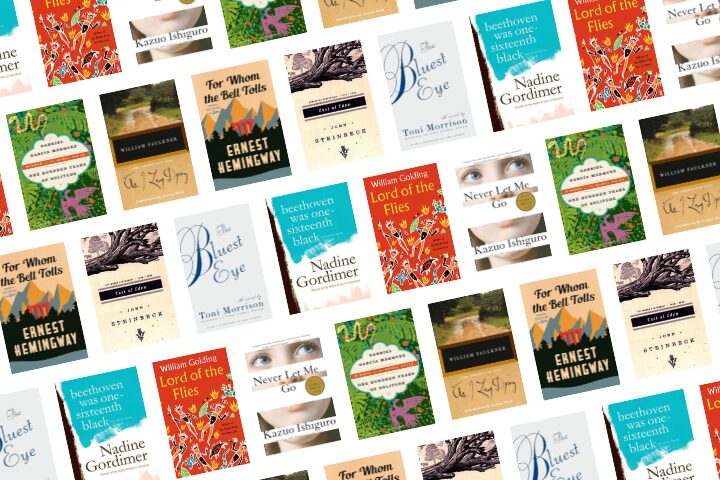

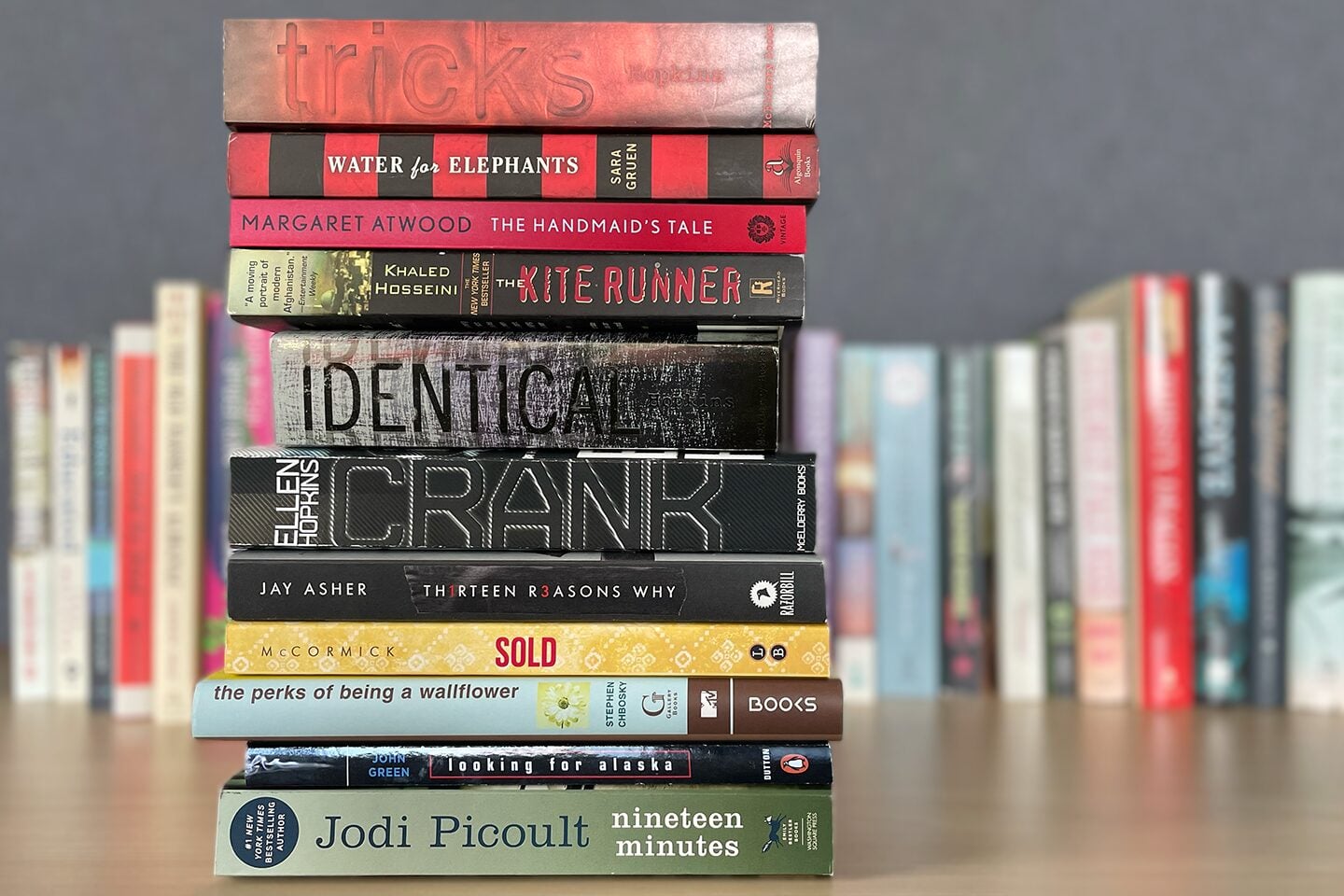

Though young adult books that include depictions of or allusions to sex are nothing new, criticism of them has exploded in the past few years. Book banners have pulled thousands of works with even a trace of sexual content off of shelves, denouncing them as “pornographic,” “obscene,” and “harmful to minors.”

A report released by PEN America in February found that 43% of all titles banned in the 2023–24 school year, or a total of 1,817 works, contained sex-related themes or content. Of those titles, the vast majority, or 92%, depicted consensual sexual experiences.

Looking at the most commonly banned books in that school year, the attack on sexual content is even more obvious: Of titles banned in two or more districts, 57%, or a total of 622 titles, included depictions of or references to sex.

In response to this escalating trend, we turned to the experts — authors and editors of young adult fiction — to inquire about the role sex plays in the literature they create. How do they determine what content is and isn’t age relevant? What value do they think literature with sexual content holds for young readers? And how are they responding to growing fear and outrage about the books they write and edit?

In the first installment of this interview series, we spoke to Andrew Karre, Executive Editor at Penguin Random House’s Dutton Books for Young Readers. Over the course of his career, Karre has edited children’s books, middle-grade fiction, and nonfiction — but if he’s known for anything, he said, it’s young adult literature. Among the YA authors whose books Karre has edited are E. K. Johnston, A.S. King, and Ashley Hope Pérez.

In this interview, Karre shares three overarching insights about the thoughtful depictions of teenage sexuality that appear in the novels he’s helped bring to life.

There’s no such thing as sex-free young adult literature.

First, Karre explained, it’s essential to understand that he doesn’t believe that he’s helping authors create “books for teenagers.” “If you replace ‘I’m making books for teenagers’ with ‘I’m making books for adults,’ you sound like a fool,” he said. “Like, what does that even mean? It’s far too broad a category, and it’s not interesting. It’s demeaning to actual teenage readers to think that you could make something that is uniquely appealing to all of them.”

Instead, Karre sees YA books as opportunities to explore facets of “teenageness,” a term that encompasses a vast array of experiences.

“Once you approach it that way, what is a part of teenage experience?” Karre asked. “Sex. Whether actually having it or imagining having it, sex is inextricable from 13- to 19-year-olds.” Of course, Karre acknowledged, YA fiction features plenty of aromantic and asexual characters — but like straight or other queer characters, they too have or are gaining an awareness of their sexual identities.

Just over half of the young adult fiction Karre edits include either explicit depictions of sex or “fade-to-black scenes,” in which the narration heavily alludes to the possibility of sex. But YA novels that don’t acknowledge the existence of sex whatsoever? “Hard to imagine.”

It’s difficult to know what to say to anyone who thinks there’s a way to wall off sexual content from teenagers, he said, as it seems like they’re “just asking for the sky to be a color other than blue.”

“If, all of a sudden, it became impossible to publish YA novels with sex in them, I think it would effectively become impossible to publish YA novels as I understand them,” Karre concluded. “I don’t think that’s hyperbolic at all.”

Some sexual content is “inappropriate” for teenage readers — but not in the way you’d assume.

Sex in YA novels should steer clear of two “poles of inappropriateness,” Karre said. It shouldn’t be idealized or titillating, unlike sex in pornography or romance novels. But it also shouldn’t fall under what he termed “wish-fulfillment” sex for adults, or purely didactic scenes in which characters model maturity and gracefulness for their readers.

Instead, Karre said, the portrayals of sex in YA novels should strive to mirror the reality of teenage sex, which means they frequently feature a good deal of both awkwardness and tenderness. “Teenagers aren’t good at having sex. They’re good at wanting to have sex, but these are inexperienced people who feel tremendously nervous and awkward,” he said.

“Eroticism comes from competence. Teenagers sort of power through competence with just sheer force of will,” Karre continued. “There’s a certain amount of laughing and fumbling and giddy nervousness…but it’s also hopeful and caring.”

Indeed, regardless of how messy the sex is, readers aren’t invited to laugh at the characters participating in it, Karre emphasized. Depictions of sex don’t create emotional distance between characters and readers; instead, they bring them together and provide readers with the opportunity for self-reflection.

Literature serves as a safe, ethical way for young readers to learn more about their own sexual desires and experiences.

“The overwhelming majority of depictions of sex that teenagers are encountering are not honest…and if we’re talking about pornography, they’re often ethically problematic,” Karre said. Books, on the other hand, offer young people sincere, nuanced portrayals of sex — and they’re guaranteed to be free of exploitation.

Candid literature about sex can provide readers with “relief and recognition” — a statement true of depictions of both straight and queer sex, Karre said, though he added that there’s an additional impetus to illustrate queer sex with honesty and clarity, given how frequently our culture obfuscates and shames it.

Ultimately, he said, book banners who want to rid young adult fiction of sexual content betray a fundamental misunderstanding of both literature and teenagers. Teenagers frequently lack any kind of sexual experience, but many are still avid readers with an insatiable desire to learn more about themselves and the world around them. “To meet that readership with a half-effort, with disingenuousness, without candor? I’d rather dig ditches.”