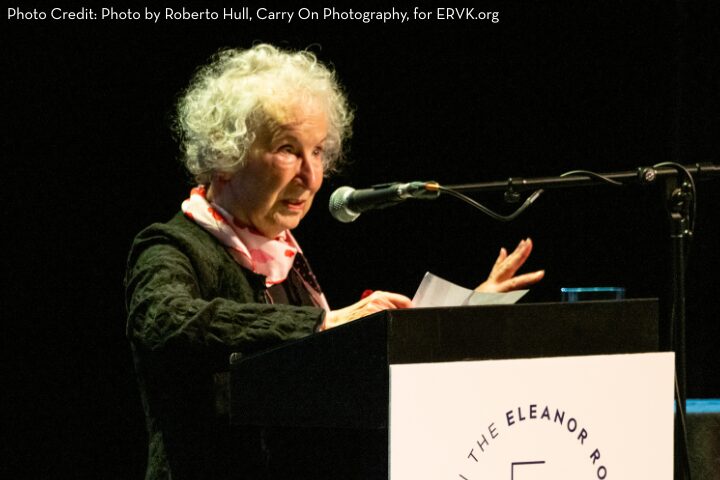

Forty years after publishing The Handmaid’s Tale, Margaret Atwood remains one of the most banned authors in the United States, and her handmaids have become symbols of resistance to creeping authoritarianism.

Atwood accepted the Eleanor Roosevelt Center’s Bravery in Literature award, co-presented with PEN America, on Oct. 11. Following her remarks, Atwood was interviewed on stage by Joe Donahue, a journalist with WAMC, an NPR affiliate (Northeast Public Radio) in Dutchess County, who hosts The Book Show. What follows is the text of her acceptance speech and excerpts of her conversation with Donahue.

Margaret Atwood Accepts the Bravery in Literature Award

Thank you. There’s a lot going on in this room tonight, and that’s quite cheering, because as long as there are rooms like this in the United States of America, with a lot going on in them, you are not living in a fascist dictatorship. Because if you were, none of us would be here. We’d be either six feet under or in some form of Alcatraz. And you’re not. You’re right here. So thank you for being here and cheering me up.

It’s a great honor to be receiving the Eleanor Roosevelt Lifetime Achievement Award for Bravery in Literature. For people of my generation, the war babies, a dwindling demographic, Eleanor Roosevelt was a towering figure. Writing recently about my partner Graeme Gibson’s father, who was a general in the Canadian Army and who was at Monte Cassino, I was researching the journalist Martha Gellhorn, who was covering that battle for Collier’s magazine.

I discovered that Eleanor Roosevelt was a friend and encourager of young Martha, as she was a friend and encourager to many women. Martha Gellhorn is my idea of real bravery in literature. She put her life on the line repeatedly, although in an age when journalists are not being routinely targeted and murdered as they are today.

Nor do I live in a country in which a bullet in the back of the head, or years of being locked up in a prison or a gulag, are the price paid for writing and publishing something that offends an autocratic regime.

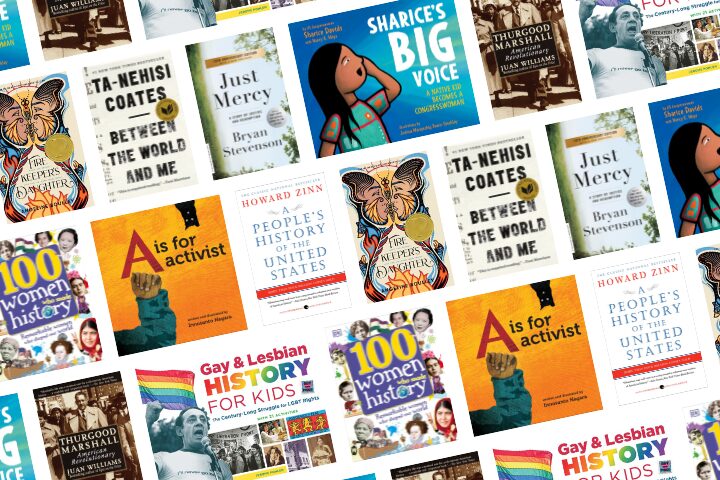

So far, the worst that can happen in North America is having your book banned in schools and libraries, getting attacked online, whether by left or right, and getting the occasional wacko death threat, or, conversely, letters from men who want me to dress up in black leather and walk on them. In high heels. My being 85 seems to be no deterrent. There is hope for us all.

If I had a job, I could be fired. But I don’t have one. I’m also old enough that I don’t give much of a hang about nasty adjectives. So, young risk-taking writers. Hang in there. I’m proud of you. And I wish you very good luck. Eleanor Roosevelt would have done the same. I will cherish this deeply meaningful award. Thank you very much to PEN and to the Eleanor Roosevelt Center.

In Conversation With Margaret Atwood

On the future: “Nobody actually knows the future because there are many possible futures. And the future we get is going to depend partly on what we do in the present. So the choices we make now are going to have something to do with the future.”

On young people reading The Handmaid’s Tale: “I don’t think this is a book that should be given to kindergarten children. Anyway, they can’t read. I did not write it as a young adult novel. I wrote it as a novel for adults. But kids are a lot older now than they used to be, and anyway when I think of what we got taught in school, some of it was pretty wild. It wasn’t that there was 19th century sex right on the page because they didn’t print that, but it was off in the shrubbery and you just had to deduce what was going on. Adultery, wife-swapping, illegitimate children – this is Thomas Hardy.”

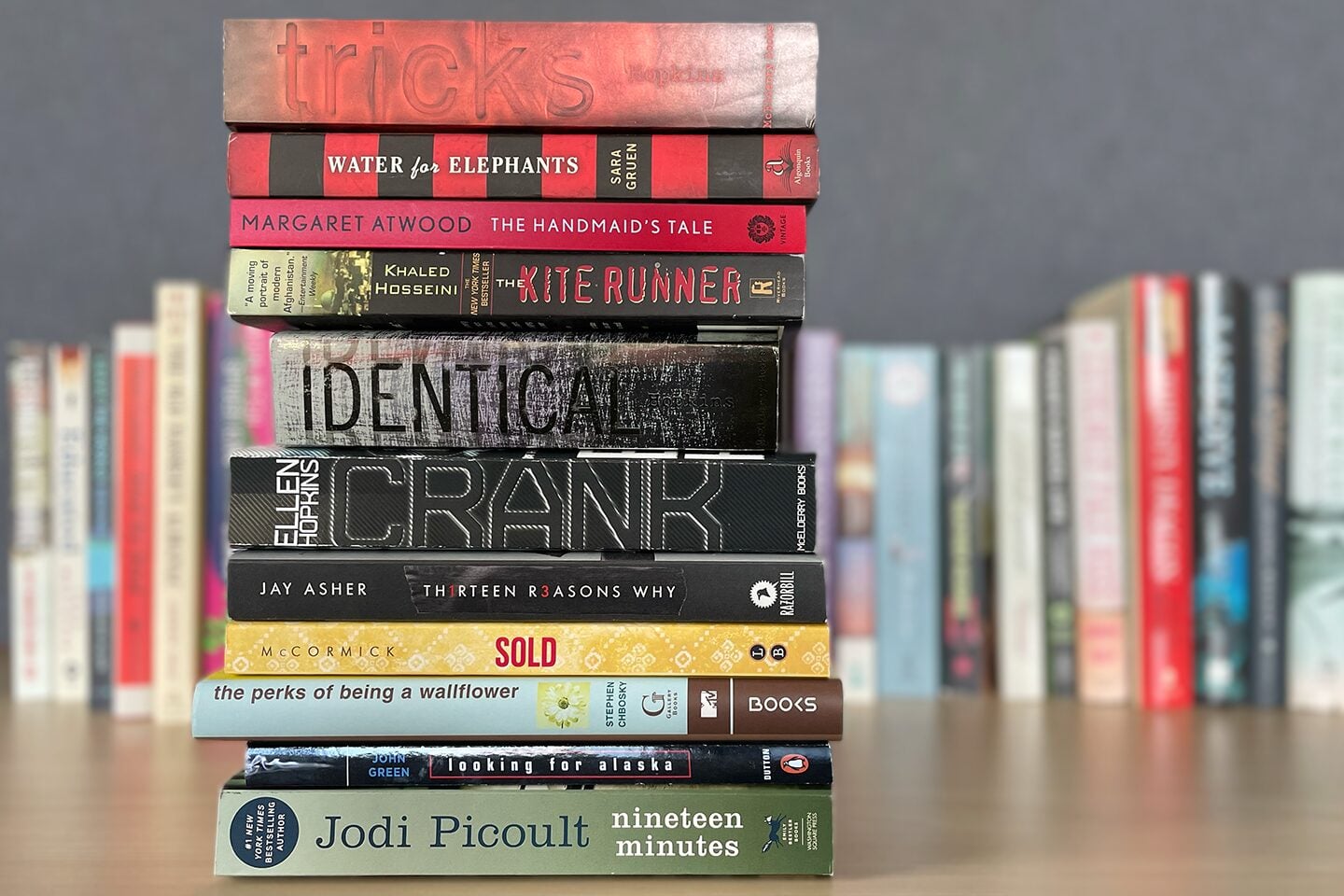

On book bans: “Usually book banning happens when people are feeling angry and they feel somebody has to be blamed for something. And it’s also usually a power grab on behalf of a certain group of people who want to demonstrate their dominance by squashing other people underfoot. So I think they should take up knitting, you know?”

On the corrosive effect of censorship: “It can have a dampening effect, but it can also, for other people, have an invigorating effect. … I lived through the Cold War and I visited communist bloc countries and knew writers from there, and knew writers who had escaped from there. So I knew there was something called samizdat, which was things people wrote but couldn’t publish because the regime wouldn’t let them. So they copied these things out and passed them from hand to hand. And that was samizdat. A couple of books I could mention were written piecemeal, concealed, smuggled out, to the West and published there. And we all knew about that. So think of what it would take to be a writer in one of those countries under those circumstances, and continue writing and also take the risk of smuggling your book out. You know, this is very risky business. You could be shot, and people are in other countries now being shot for what they’ve written. That’s why we have PEN, you know.”

On librarians and why they are being targeted: “It is power to be a librarian. But because librarians are powerful, other people who want to be more powerful will target them. And we’ve seen that in Canada, too. … People who really stand up are risking their jobs, as we know, and that’s when they need the community to stand behind them and say, ‘No, we do not want this person who is serving us, our community, to be fired for serving our community.’”

On defending human rights: “I have been canceled and attacked quite a lot. But I am of the human rights generation. I’m very old. I remember when this stuff was new and people were very enthusiastic about it. And let us just say that every other set of rights is a subset of human rights. So you cannot have women’s rights without human rights. And you cannot have the rights of any other identity without human rights first. …”

“It’s never true when people say ‘That can’t happen here.’ ‘That’ – whatever it is – can happen anywhere, given the conditions. And I did gather quite a lot of ‘That can’t happen here’ when The Handmaid’s Tale first came out. One group of people said, ‘That can’t happen here. America is the shining light of democracy during the Cold War.’ People in Europe just didn’t believe The Handmaid’s Tale. They didn’t believe that America could ever go that way. Another group of people in this country said … ‘How long have we got?’ And that was in 1985. So yes, it’s always possible. And yes, the best thing to do is to be aware of the possibilities and to try to block the attempt when it first starts happening. Because when you’re halfway down the slippery slope, it’s not far to the bottom.”

On working on the TV series adapted from The Handmaid’s Tale: “If I really strongly object to something, I talk to the showrunner. His name is Bruce Miller, and he’s got that job because he read that book as a teenager in high school and vowed that when he grew up, that’s what he was going to do. And I think that happens with a lot of things that people do later in life when they have the power and ability. It’s something that’s inspired them as young people in high school. And that’s why high school libraries are so important.

“So I have said to Bruce, ‘Bruce, you can’t kill that baby.’ And he says, ‘Oh, I wasn’t going to.’ ‘And by the way, you cannot kill Aunt Lydia.’ And he says, ‘Oh no, no, no, I wasn’t going to do that either.’ … Generally, the team is extremely dedicated and I’ve had some pretty unmentionable things made of some of my work, but this is not one of them. This is really dedicated. And, they have followed the same rule. They don’t put anything into the scripts that they cannot show a real life reference for. So they’ve got researchers who comb through history and say, ‘Oh, yes, this is where they had mass drownings.’ That was the French Revolution, in case you’re interested.”

On her forthcoming memoir Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts: “In my mind, a memoir is what you remember, and what you mostly remember, looking back over decades on this planet, is stupid things you did, catastrophes that occurred, stuff like that. … The stupid things you did aren’t funny at the time, and nor are, say, your romantic entanglements when you were 17, you know, deeply wounded heart. But when you’re 30, you think that’s funny. And when you’re 65, you can’t remember that person’s name, just to give you a bit of hope out there. … Mostly it was a lot of fun. And sometimes it wasn’t. … If you write a memoir when you’re 25, you actually don’t know how it’s going to end. But I kind of do.”

Help PEN America Fight Book Bans

PEN America’s research reveals that there have been more than 22,800 book bans in 45 states since 2021. Your support is critical to the fight against book bans. Please donate today.