America’s Censored Classrooms 2024

Refining the Art of Censorship

Since 2021, PEN America has tracked state-level educational censorship legislation in our Index of Educational Gag Orders. In this report, we analyze the educational censorship laws introduced and passed in the now mostly concluded 2024 legislative sessions, with a particular focus on higher education.

Our top-line numbers:

In 2024, state governments enacted 8 bills or policies that PEN America defines as educational gag orders—direct restrictions on educational speech in the classroom.

Of these, 3 focused solely on colleges and universities, 3 focused only on K-12 schools, and 2 included restrictions on both.

State governments also enacted 5 additional higher education bills that endanger academic freedom in ways that are not direct censorship, such as politicization of university governance; bans on diversity, equity, and inclusion; and restrictions on faculty tenure.

In all, 47 educational gag orders and 10 other higher ed restrictions were enacted in 23 states between January 1, 2021, and October 1, 2024.

Our key findings:

In 2024, higher ed censorship policies went underground—and became even more dangerous. Supporters of censorship largely abandoned open calls for restricting faculty speech; instead, they embraced—to great effect—camouflage, misdirection, and actions behind the scenes.

The campaign to censor higher ed adopted or continued three key tactics: (1) disguising educational censorship laws by attaching them to other popular goals; (2) expanding their targets to undermine the broader system that sustains academic freedom, such as shared governance, faculty tenure, and accreditation agencies; and (3) bullying universities into adopting restrictions without a law.

The impact of 2024’s educational censorship laws has been devastating, but resistance continues to grow. Both legal challenges and activism have been successful, and educational censorship laws have been revealed as unpopular, forcing supporters of censorship to change their approach radically.

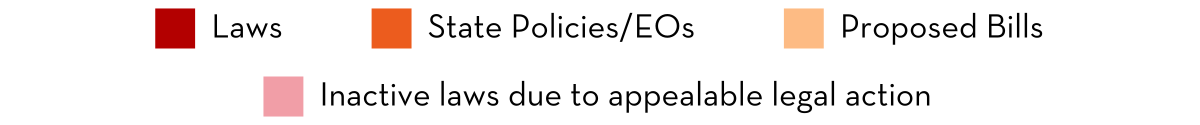

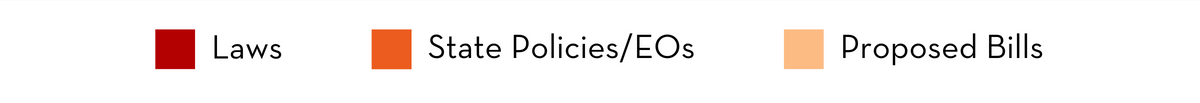

Educational Gag Orders, K-12 and Higher Ed, 2021-2024

Higher Education Restrictions, including educational gag orders and other restrictions, 2021-2024

PEN America Experts:

Senior Analyst, PEN America

Director, State and Higher Education Policy

Introduction

Educational censorship is changing. The educational gag orders of 2021 that directly prohibited teaching specific topics are largely a thing of the past. In 2024, most educational censorship bills don’t fulminate against critical race theory or the New York Times’ 1619 Project. Instead, they are more likely to attach themselves to a worthy goal, like promoting “institutional neutrality” or “viewpoint diversity,” combating antisemitism, or treating all students equally.

But Americans should make no mistake: This is censorship by stealth.

Since 2021, PEN America has tracked and analyzed educational gag orders: state legislation and policies that restrict teaching about topics such as race, gender, and LGBTQ+ identity in educational settings.1PEN America Index of Educational Gag Orders, https://airtable.com/appg59iDuPhlLPPFp/shrtwubfBUo2tuHyO; Jonathan Friedman and James Tager, Educational Gag Orders: Legislative Restrictions on the Freedom to Read, Learn, and Teach (PEN America, November 2021), https://pen.org/report/educational-gag-orders/; Jeremy C. Young, Jeffrey Adam Sachs, and Jonathan Friedman, America’s Censored Classrooms (PEN America, August 2022), https://pen.org/report/americas-censored-classrooms/; Jeffrey Adam Sachs and Jeremy C. Young, America’s Censored Classrooms 2023: Lawmakers Shift Strategies as Resistance Rises (PEN America, November 2023), https://pen.org/report/americas-censored-classrooms-2023/. Over that time, most educational censorship bills and policies followed a settled pattern. Certain terms and phrases appeared over and over in legislative text. Even the rhetoric of “anti-wokeness” used by lawmakers had a familiar shape and drew on recognizable tropes.

But in 2024, the playbook changed. In this year’s state legislative sessions, most of which took place between January and June, policymakers largely abandoned straightforward calls for censorship, opting instead to disguise their intentions through euphemism and misdirection. This tactic was essential for continuing the campaign to censor America’s classrooms, amid a gauntlet of legal challenges, mounting evidence that gag orders are unpopular and carry no political benefit, and growing momentum for efforts to block censorship legislation.

From Stop WOKE to Censorship by Stealth

From its earliest stages in 2020—when President Trump issued Executive Order 13950, on “combating race and sex stereotyping,” with the initial list of so-called “divisive concepts” —the state legislative campaign to censor educational speech appeared to be motivated by a simple political calculation: that moderate and swing voters would rally to conservative candidates who were seen as opposing “wokeness” in public education.2Executive Order 13950, “Combating Race and Sex Stereotyping,” September 22, 2020, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/presidential-actions/executive-order-combating-race-sex-stereotyping/. Following the popularity of the 1619 Project, and in the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd, many Republicans, including President Trump, sought to foment and sustain a backlash against discussing race and racism in public schools, to harness the issue for political gain. With fiery rhetoric and the force of state and federal law, they targeted a widening array of topics in schools, moving from the 1619 Project to critical race theory (CRT), as well as sexuality, gender, American history, and even social-emotional learning (SEL). “I look at this and say, ‘Hey, this is how we are going to win,’” former Trump chief strategist Steve Bannon said in 2021. “I see 50 [House Republican] seats in 2022. Keep this up.”3Quoted in Theodoric Meyer, Maggie Severns, and Meridith McGraw, “‘The Tea Party to the 10th Power’: Trumpworld Bets Big on Critical Race Theory,” Politico, June 23, 2021, https://www.politico.com/news/2021/06/23/trumpworld-critical-race-theory-495712.

For these strategists, the come-from-behind victory of Glenn Youngkin in the November 2021 Virginia gubernatorial race seemed to be proof of concept.4Maeve Reston, “How Glenn Youngkin May Have Forged an Education Roadmap for Republicans,” CNN, November 4, 2021, https://www.cnn.com/2021/11/04/politics/glenn-youngkin-republicans-education-2022-midterms/index.html. Youngkin’s campaign was based in no small part on the slogan of “parents’ rights” in education, particularly following a debate where his rival said, “I don’t think parents should be telling schools what to teach.”5Sara Burnett and Hannah Fingerhut, “Youngkin Win Built by Small Gains in Key Groups,” Associated Press, November 3, 2021, https://apnews.com/article/virginia-election-ap-votecast-survey-75520c5c9a245bee384526abc138a61a. This comment was widely seen as an unforced error, one that Youngkin and his fellow Republicans hurried to exploit. In a memo titled “Lessons from Virginia,” House Republican Study Committee chair Rep. Jim Banks6Jim Banks to Republican Study Committee, November 2, 2021, https://www.politico.com/f/?id=0000017c-e386-d8e1-a57c-ebfff8d40000&nname=playbook. urged candidates to fight “racist CRT curricula” in schools and to promise to pass something called the “CRT Transparency Act.” Six months later, a second memo from the RSC bluntly titled “Critical Race Theory Memo” urged Republican House members to “lean into the culture war” because “the backlash against Critical Race Theory is real.”7Jim Banks to Republican Study Committee, June 24, 2021, https://rsc-hern.house.gov/critical-race-theory-memo.

That was the theory, at any rate. In practice, Youngkin’s victory proved difficult to replicate. In the 2022 midterm elections, Republicans picked up only nine of the fifty House seats Bannon had forecast, and Republican gubernatorial candidates who followed the Youngkin playbook lost key races in Arizona, Kansas, Michigan, and Wisconsin.8“Seats in Congress Gained/Lost by the President’s Party in Mid-Term Elections,” American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/statistics/data/seats-congress-gainedlost-the-presidents-party-mid-term-elections; Melissa Gira Grant, “The Arizona Republican Primary Is Ground Zero for America’s Hysteria over Critical Race Theory and Drag Queens,” TNR, July 28, 2022, https://newrepublic.com/article/167175/arizona-republican-primary-critical-race-theory-drag-queens-hysteria; Hannah Farrow, “Laura Kelly Keeps Kansas Governor Seat for Another Term,” Politico, November 9, 2022, https://www.politico.com/news/2022/11/09/laura-kelly-derek-schmidt-kansas-governor-race-results-2022-00064758; Simon Schuster, “Culture Wars Take Center Stage in Tudor Dixon’s Education Proposals,” MLive, September 28, 2022, https://www.mlive.com/public-interest/2022/09/culture-wars-take-center-stage-in-tudor-dixons-education-proposals.html; Adam Edelman, “Wisconsin GOP Looks to Weaponize Critical Race Theory in Governor’s Race,” NBC News, February 14, 2022, https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/wisconsin-gop-looks-weaponize-critical-race-theory-governors-race-rcna15546. Of course these outcomes turned on many factors, but the “anti-woke” strategy also came up short in some races where education was front and center, like elections in several states for local school boards.9Juan Perez Jr. and Andrew Atterbury, “‘We Can’t Have 2 Countries’: 2022’s Elections Foreshadow New Divides in Education,” Politico, December 14, 2022, https://www.politico.com/news/2022/12/14/education-critical-race-theory-schools-00072983. Finally, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, who had done more than any other elected official to implement bans on CRT and diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) offices and programming in public educational institutions, saw his 2024 presidential campaign flame out as voters abandoned his “war on woke” rhetoric and record.10David Smith, “Ron DeSantis Put Nearly All His Eggs in the Basket of a ‘War on Woke,’” Guardian, January 21, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2024/jan/21/ron-desantis-republican-presidential-candidate-dropped-out-analysis.

By 2024, it became clear that supporters of educational censorship, especially at the K–12 level, had seriously underestimated how much Americans support their local schools and the teachers who work there. Yes, approval for public schools in general is declining, particularly among Republicans.11Rachel Minkin, “About Half of Americans Say Public K–12 Education Is Going in the Wrong Direction,” Pew Research Center, April 4, 2024, https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/04/04/about-half-of-americans-say-public-k-12-education-is-going-in-the-wrong-direction/. However, when parents of K–12 students are asked about their feelings toward their own school and its teachers, their responses are overwhelmingly positive.12Corey Smith, “Gap Grows in How Americans See Education Overall, Their Own Kids’ Schools,” National Desk, September 7, 2023, https://thenationaldesk.com/news/americas-news-now/gap-grows-in-how-americans-see-education-overall-their-own-kids-schools-teachers-classrooms-politics-curriculum-textbooks-families-children. Some 76 percent report being satisfied with their local schools, and 73 percent rate their children’s teachers as “excellent” or “good.” Moreover, while some parents have concerns about what their children are learning in the classroom, the vast majority emphatically reject any attempt by state legislators to influence curricula on these issues.13McCourtney Institute for Democracy, Mood of the Nation: What Americans Think Schools Should Teach About Slavery and Racism, and Who Should Influence That Curriculum, June 16, 2023, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5c9542c8840b163998cf4804/t/648b5337df908d33c9320aad/1686852409681/MOTN-APM-Schools-CRT%28May2023%29.pdf. Meanwhile, 88 percent of public school parents and 78 percent of all adults trust local public schools to select books for school libraries; most are more concerned about book restrictions than about the appropriateness of available materials.14Langer Research Associates, Americans’ Views on Book Restrictions in U.S. Public Schools 2024, Knight Foundation, August 21, 2024, https://knightfoundation.org/reports/americans-views-on-book-restrictions-in-u-s-public-schools-2024/.

For all these reasons, lawmakers in 2024 largely abandoned the splashy press conferences of the DeSantis era and pulled back from direct and explicit censorial legislation. Instead, they embraced a campaign of stealth censorship—a more devious approach that was more difficult for free expression advocates to expose or oppose.

The three key tactics of this campaign were as follows:

Disguise educational censorship legislation by allying it with some worthy or popular cause.

Censor indirectly, by undermining the support structures at universities that protect intellectual freedom in the classroom, rather than directly, by placing official restrictions on speech.

Whenever possible, accomplish censorship by informal pressure, bullying, or threats rather than formal legislation.

In what follows, PEN America explores how lawmakers are refining the art of educational censorship by putting these tactics into practice.

Readers will note that the total number of educational gag orders proposed in 2024 was lower than in recent years. The number that became law was also lower. But these facts conceal a much more disturbing reality. Increasingly, educational gag orders are only a small part of a much larger story, as a whole battery of other kinds of legislation, targeting everything from faculty tenure to shared governance to teacher training programs, have actually expanded an all-out assault on educational speech. And even this does not tell the whole story, as more and more censorship takes place off the books through informal intimidation and backroom pressure.

As PEN America has noted in the past, these restrictions, for the most part wielded by conservatives to target elements of progressive speech, have far-reaching consequences that cross ideological and partisan lines. They set a precedent for political interference in education that could easily be turned against conservatives in the future and, indeed, has been in the recent past. Preserving the freedom to learn, teach, and share ideas in educational settings benefits everyone and every viewpoint; threatening those things risks a vast chilling effect that constrains not only diversity of identity but diversity of thought across all categories and viewpoints.

Fortunately, several positive trends first identified in 2023 continued to gain steam in 2024. Legal resistance to gag orders has scored a number of major wins, dealing significant setbacks to would-be censors. Political resistance to these proposals has also increased, amid growing public skepticism toward restrictions on educational speech and recognition that these laws are damaging to students’ education.

An important note: After years of overlap between educational censorship legislation targeting the higher education and K–12 sectors, in 2024 only two educational gag order laws, Alabama’s SB 129 and Utah’s HB 261, contained restrictions on both higher ed and K–12 settings. The strategies behind censorial legislation in both arenas diverged, too, with educational intimidation bills—described in our 2023 report of that name—increasingly the focus of those advocating legislative censorship in K–12.15Sam LaFrance and Jonathan Friedman, Educational Intimidation: How “Parents’ Rights” Legislation Undermines the Freedom to Learn (PEN America, August 2023), https://pen.org/report/educational-intimidation/.

Accordingly, in America’s Censored Classrooms 2024, PEN America has chosen to focus primarily on educational censorship in higher education settings, although we still include K–12 gag orders in our Index, in the Appendix of new laws and policies enacted, and at selected points in the text.

Increasingly, educational gag orders are only a small part of a much larger story, as a whole battery of other kinds of legislation, targeting everything from faculty tenure to shared governance to teacher training programs, have actually expanded an all-out assault on educational speech.

Outline

America’s Censored Classrooms 2024 has a different structure from that of previous years. We begin with the sort of overview of the 2024 legislative session by the numbers that will be familiar to readers of earlier reports. But thereafter, the focus shifts. Instead of a typology of this year’s educational censorship legislation, we organize the following sections by tactic.

Tactic I explores how lawmakers have begun to disguise educational censorship legislation by pairing it with worthy causes, like promoting “viewpoint diversity” and combating campus antisemitism.

Tactic II investigates continuing efforts by lawmakers to exert ideological control over university governance and decision-making in order to undermine the support structures in higher education that make academic freedom possible. DEI restrictions continued to be a major type of this kind of legislation, but they were joined by others, including mandatory institutional neutrality bills and attacks on shared governance.

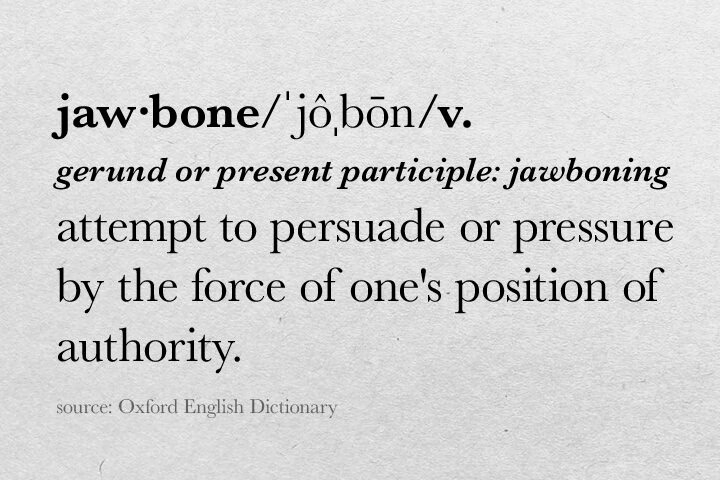

Tactic III looks at the mechanics of jawboning, the set of informal ways that government officials bully, threaten, or intimidate educators into silence.

The report concludes by analyzing the resistance to educational censorship, where major victories have been won and new strategies developed. It also offers some predictions of what to expect in 2025.

Educational Censorship by the Numbers

Fifty-six legislative educational gag orders were filed in 2024. This marks a decline compared to the last two years, when nearly twice as many were introduced by lawmakers. Seven became law and one was implemented via executive order, a total that is also among the lowest in recent years. Yet the gag orders adopted in 2024 include some of the most pernicious assaults on educational speech that PEN America has encountered.

The overall decline in educational gag orders also masks some of the more subtle— but no less alarming—ways that lawmakers are attacking our country’s educators. Indeed, 2024 seems to have been a year of experimentation. During the state legislative sessions, lawmakers tried out a range of tactics to stifle academic freedom and free speech in the nation’s classrooms.

Finally, this past year also saw the introduction of 29 bills with higher education provisions that, while not constituting direct censorship of educational speech the way gag orders do, would have eroded institutions and practices that make academic freedom in colleges and universities possible. Provisions of this type include attacks on tenure, shared governance, and DEI offices, along with a host of other restrictions on the independence of universities from direct ideological control by the government. This is an acceleration of a trend that PEN America first noted in 2023. Five bills of this type became law.

Finally, 2024 saw a renewed focus on higher education. The same number of bills and policies that became law targeted colleges and universities as K-12 institutions, making higher education, for the first time, a primary site of educational censorship. Three higher education gag orders became law or policy, compared with 3 that restrict speech in K–12 institutions, and 2 that would do so in both.

K–12 schools remain an area of focus for would-be censors, and bills censoring the nation’s schools still narrowly led those censoring higher ed in the number of bills introduced. Thirty-five K–12 gag orders were introduced in 2024, the lowest number since PEN America began tracking such legislation in 2021. Of these, 5 became law, including a “Don’t Say Gay” –style bill in Louisiana and a quartet of bills banning instruction on certain concepts related to race and sex in Alabama, Louisiana, South Carolina, and Utah.16Louisiana HB 122, https://legiscan.com/LA/text/HB122/id/3011071; Alabama SB 129, https://legiscan.com/AL/text/SB129/id/3000123; South Carolina https://www.scstatehouse.gov/query.php?search=DOC&searchtext=Partisanship%20Curriculum&category=BUDGET&year=2023&version_id=7&return_page=&version_title=Appropriation%20Act&conid=43525128&result_pos=0&keyval=51636&numrows=10; Utah HB 261, https://legiscan.com/UT/text/HB0261/id/2907864.

Why the decline in K–12 educational gag orders compared with previous years? First and foremost, they are not particularly popular. As PEN America noted in America’s Censored Classrooms 2023, national surveys show widespread and bipartisan opposition to state lawmakers deciding what gets taught, read, or discussed in K–12 schools.17Jeffrey Adam Sachs and Jeremy C. Young, America’s Censored Classrooms 2023: Lawmakers Shift Strategies as Resistance Rises, (PEN America, November 2023) https://pen.org/report/americas-censored-classrooms-2023/. Second, much of the low-hanging fruit has already been plucked. K–12 educational gag orders of one form or another have been adopted in 23 states; attention in many of those states has now shifted toward other sorts of school “reform” bills—for example, book banning legislation, educational intimidation bills, and school voucher programs.18“Book Bans,” PEN America, https://pen.org/issue/book-bans/; Sam LaFrance and Jonathan Friedman, Educational Intimidation: How ‘Parent’s Rights’ Legislation Undermines the Freedom to Learn, (PEN America, August, 2023), https://pen.org/report/educational-intimidation/. Finally, for the first time in 2024, students, teachers, and other free speech advocates have successfully challenged K–12 gag orders in court.

Not all gag orders proposed or passed in 2024 adopt the prevailing “censorship by stealth” approach. Some, like Alabama’s SB 129 and Florida’s HB 1291, were quite brazen about their censorial intent.19Alabama SB 129, https://legiscan.com/AL/text/SB129/2024.

Policy Spotlight: Alabama’s SB 129

Alabama’s SB 129 prohibits public K–12 schools and colleges and universities from requiring that students attend or participate in coursework in which certain ideas related to race, color, religion, sex, ethnicity, or national origin are promoted. SB 129 is a “classic” educational gag order, with language drawn from the Trump administration’s 2020 executive order “combating race and sex stereotyping.”20Executive Order 13950, “Combating Race and Sex Stereotyping,” https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/09/28/2020-21534/combating-race-and-sex-stereotyping.

SB 129 also includes a few unique features. Not only would its language prohibit teachers or professors from encouraging students to feel guilt for historical wrongs committed by members of their identity group, as do most educational gag orders of this type; it would also ban them from assigning readings whose authors describe feeling this sort of guilt. Since “national origin” is one of the protected categories, the law would in effect ban a reading by a German citizen expressing guilt that her country perpetrated the Holocaust.

Moreover, while SB 129 does not ban DEI programming in its entirety, it does include explicit restrictions on any programming “where attendance is based on” identity category—which could restrict, among other things, programming for international students, or formal recognition of a Black student union.

Other gag orders proposed in 2024, like New Hampshire’s SB 1153, were too bizarre to fly under the radar.21New Hampshire HB 1153, https://legiscan.com/NH/text/HB1153/2024. This bill, which purported to mandate a curriculum on the evils of communism, would have required public K–12 schools to teach students about “Western intelligence agencies’ links to the private island of Jeffrey Epstein” and how “Marxist cult beliefs” have “parasitized sects of Judaism.” Oklahoma’s SB 1305 did such a poor job banning something it called “DEI-CRT” content in higher ed that it would actually have required faculty in every department to discuss “historical movements, ideologies, or instances of racial hatred or discrimination including, but not limited to, slavery, Indian tribe removal, the Holocaust, or Japanese-American internment.”22Oklahoma SB 1305, https://legiscan.com/OK/text/SB1305/2024. And West Virginia’s HB 5656 would have prohibited public K–12 schools and institutions of higher education (and, via restrictions on state funding, private ones as well) from “allowing” any class, speech, or presentation where the presenter “states that there are more than two genders.” This prohibition would likely have applied to students making a “presentation” in class.23West Virginia HB 5656, https://legiscan.com/WV/text/HB5656/2024. Thankfully, none of these bills became law in 2024.

Policy Spotlight: Florida’s HB 1291

Florida, at the epicenter of previous years’ educational censorship legislation, remained active on this front in 2024. Florida’s HB 1291, which became law in 2024, attacks the speech of both K–12 teachers and higher ed.24Florida HB 1291, https://legiscan.com/FL/text/H1291/id/2953485. That is because HB 1291 goes after teacher preparation programs, the university departments and schools where the next generation of Florida K–12 teachers is trained. And what it does to these programs is alarming.

Under the law, these university programs may not “distort significant historical events or include a curriculum or instruction that teaches identity politics, violates [the Stop WOKE Act], or is based on theories that systemic racism, sexism, oppression, and privilege are inherent in the institutions of the United States and were created to maintain social, political, and economic inequities.”

According to Governor DeSantis, HB 1291 is meant to “prohibit the indoctrination” of prospective teachers.25“DeSantis Signs Bill to Prevent ‘Indoctrination’ in Teacher-Training Programs,” 6 South Florida, May 3 2024, https://www.nbcmiami.com/news/local/desantis-signs-bill-to-prevent-indoctrination-in-teacher-training-programs/3301880/. In truth, it does the opposite. First, it directly censors both public and private college and university faculty who work in these programs. What constitutes a “significant historical event,” and what does it mean to “distort” one? The law does not say. Into that void, universities and faculty will project their own fears and paranoia. Some will respond by parroting whatever stance they think will best please the Florida government, which in 2023 approved a K–12 curriculum arguing that some slaves benefited from slavery.26Antonio Planas, “New Florida Standards Teach Students That Some Black People Benefited from Slavery Because It Taught Useful Skills,” NBC News, July 20, 2023, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/new-florida-standards-teach-black-people-benefited-slavery-taught-usef-rcna95418. Others will simply skip over certain topics altogether. Same with the ban on “identity politics,” a concept whose meaning is so contested that it could encompass everything from the US civil rights movement and the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II to contemporary immigration policy.

All of the above is flatly unconstitutional.27Letter to Kathleen Passidomo and Paul Renner from PEN America et al., February 28, 2024, https://cdn.pen.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/22184743/coalition_letter_against_sb_1372_hb_1291.pdf. But that has never stopped Florida’s government before. Indeed, HB 1291 also requires faculty to follow the Stop WOKE Act, a law so repugnant to the First Amendment that in 2022 a federal judge declared it “Orwellian” and blocked the state from enforcing it.28Florida HB 7, https://legiscan.com/FL/text/H0007/id/2544468; Mark E. Walker, “Order Granting in Part and Denying in Part Motions for Preliminary Injunction,” November 17, 2022, https://www.aclu.org/cases/pernell-v-lamb?document=Order-Granting-in-Part-and-Denying-in-Part-Motions-for-Preliminary-Injunction#legal-documents.

HB 1291 will have a dramatic effect on how the K–12 teachers of tomorrow do their jobs.29Paul O. Burns to Deans/Directors of Teacher Preparation Programs and School District Superintendents, May 24, 2024, https://web.archive.org/web/20240701020152/https://info.fldoe.org/docushare/dsweb/Get/Document-10234/dps-2024-69.pdf. Graduates of Florida’s teacher training programs who become history and social science and language arts teachers will enter the classroom with a more constricted and doctrinaire view of the world than they otherwise might.

Tactic I: Censorship in Disguise

One key tactic deployed by censorship advocates in 2024 was to camouflage their censorship legislation. Rather than openly advertising the ways their bills would restrict speech, as they did in previous years, they instead claimed such bills would advance laudable and broadly popular goals for higher education. Below, we examine some of the most egregious—and successful—examples.

“Viewpoint Diversity” as Camouflage

Before 2024, Indiana was surprisingly resistant to higher education censorship. Despite the GOP’s control of the governor’s mansion and both chambers of the Indiana legislature, lawmakers had enormous difficulty passing any sort of bill to restrict college and university faculty, a perennial object of criticism for many of the state’s conservatives. Of the 16 educational gag orders filed in that state since 2021, 10 target its colleges and universities—yet before this year, none had ever become law, including a high-profile failure in 2022.30Aleksandra Appleton and Stephanie Wang, “How Indiana’s Anti-CRT Bill Failed Even with a GOP Supermajority,” Chalkbeat Indiana, March 10, 2022, https://www.chalkbeat.org/indiana/2022/3/10/22971488/indiana-divisive-concepts-anticrt-bill-failed-gop-supermajority/. No other legislature in the country has made so many attempts to censor higher education, and no other state has failed so often. Not Florida, Texas, or even Missouri—which, despite leading the country with 46 educational gag orders introduced since 2021, has only ever directed 7 at higher education.

From a numerical standpoint, in other words, the Indiana legislature is unique—in its obsession with trying to restrict faculty members’ speech, and in its inability to get the job done.

Until now.

Not only did Indiana pass a higher education gag order in 2024; it passed one of the most censorial pieces of legislation that PEN America has come across since our tracking began in 2021. How? By disguising the bill in the language of “viewpoint diversity.”

Under the law, SB 202, in order to maintain employment at a public college or university, Indiana faculty have to carry out all sorts of standard academic duties: teaching courses, supervising students, conducting research, and so forth.31Indiana SB 202, https://legiscan.com/IN/text/SB0202/id/2946990. But starting this academic year, they will also have to demonstrate to the satisfaction of their board of trustees that they have:

- helped the institution foster a culture of free inquiry, free expression, and intellectual diversity within the institution;

- introduced students to scholarly works from a variety of political or ideological frameworks that may exist within the curricula established by the [college or university]; or,

- while performing teaching duties within the scope of the faculty member’s employment, refrained from subjecting students to views and opinions concerning matters not related to the faculty member’s academic discipline or assigned course of instruction.

Failure to meet these criteria can mean loss of tenure status, demotion, a reduction in salary, or even termination. Junior scholars just beginning their careers can also be denied tenure if, in the estimation of the board, they are “unlikely” to meet these criteria at some point in the future.

This sort of language may appear innocuous or even salutary, at least at first glance. And indeed, that is the entire point. The bill’s supporters in the Indiana senate framed it as an “intellectual diversity” bill that would promote neutrality in the classroom.32Ryan Quinn, “Indiana Bill Threatens Faculty Members Who Don’t Provide ‘Intellectual Diversity,’” Inside Higher Ed, February 21, 2024, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/faculty-issues/academic-freedom/2024/02/21/bill-threatens-profs-who-dont-give-intellectual. It was on that basis that Indiana politicians, despite vocal opposition and their own long record of similar failures, succeeded in making SB 202 law.33Casey Smith, “College Faculty Overwhelmingly Opposed to Bill Seeking to End ‘Viewpoint Discrimination,’” Indiana Capital Chronicle, February 15, 2024, https://indianacapitalchronicle.com/2024/02/15/indiana-college-faculty-overwhelming-opposed-to-bill-seeking-to-end-viewpoint-discrimination/.

The consequences of this language, however, are dire. First, SB 202 will incentivize bad teaching.34Megan Zahneis, “A New Indiana Law Will Enforce ‘Intellectual Diversity’ for Professors. Here’s What It Might Mean,” Chronicle of Higher Education, March 20, 2024, https://www.chronicle.com/article/indiana-has-a-new-law-enforcing-intellectual-diversity-heres-what-it-might-mean. Contrary to what the bill’s supporters claim, the smart professor will not teach students a variety of political or ideological viewpoints. Rather, many are likely to teach them the viewpoints that students expect them to teach. The goal will not be to expose students to something new; it will be to convince them that the professor has checked every box. Otherwise, how can she persuade them that all viewpoints have been addressed? And persuade them she must, as the law allows students to lodge formal complaints with the university’s governing board if they feel she has omitted some necessary theory or point of view.

Second, SB 202 will stifle faculty speech.35Keith E. Whittington, “Indiana Bill Would Mandate ‘Intellectual Diversity’ in the Classroom,” Reason, February 22, 2024, https://reason.com/volokh/2024/02/22/indiana-bill-would-mandate-intellectual-diversity-in-the-classroom/. By enabling governing boards to enforce a ban on expressing a view or opinion “not related to the faculty member’s academic discipline or assigned course of instruction” —instead of leaving this determination up to faculty themselves, as suggested by the American Association of University Professors—the law hands trustees the power to impose a subjective standard on faculty.36“1940 Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure,” American Association of University Professors, https://www.aaup.org/report/1940-statement-principles-academic-freedom-and-tenure. How do the trustees determine whether a line has been crossed? However they please. Faculty will need to anticipate their preferences and adjust accordingly, with no recourse to academic freedom protections.

SB 202 is a stunning violation of academic freedom and campus free speech. That it nevertheless became law is a testament to the appeal of “viewpoint diversity” as a smoke screen for censorship. State Senator Spencer Deery, the author and prime force behind SB 202, used this rhetorical frame to defend the law prior to passage. “By any measure,” he writes, “the current [university] system fails to adequately recruit, retain, and cultivate conservative scholars who are then empowered to foster robust, unretaliated debate.”37Spencer Deery, “In Defense of Senate Bill 202,” Based in Lafayette, Indiana, March 6, 2024, https://www.basedinlafayette.com/p/deery-in-defense-of-sb-202-indianas. SB 202, he goes on to predict, will “help an overlooked group on campus feel like they are respected and belong.”

The problem of viewpoint diversity on campus is real, and has existed for some time.38Scott Jaschik, “Professors and Politics: What the Research Says,” Inside Higher Ed, February 26, 2017, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/02/27/research-confirms-professors-lean-left-questions-assumptions-about-what-means. But SB 202 will not solve it. Indeed, there is a very good chance that SB 202 will boomerang on its conservative supporters, censoring the very people and ideas they hope to promote. As an example, Christopher Rufo, a leader of the educational censorship movement and himself a trustee at Florida’s New College, has famously declared that “the goal of the university is not free inquiry.” Could an Indiana professor who agreed with him on this point convince a trustee that they “foster[ed] a culture of free inquiry”39William A. Galston, “Ron DeSantis’s Illiberal Education,” Wall Street Journal, August 29, 2023, https://www.wsj.com/articles/ron-desantiss-illiberal-education-indoctrination-gop-candidate-constitution-advisers-florida-1c52834b. in the classroom, and therefore deserve tenure? Plainly not.

For that matter, what about Todd Rokita, the Indiana attorney general? In a legal brief defending this very law, Rokita dismissed the notion of faculty free speech. Instead, he argued that “any speech pursuant to the teacher’s ‘official duties’ and ‘professional responsibilities’ is subject to state direction.”40Ryan Quinn, “Indiana Argues Professors Lack First Amendment Rights in Public Classrooms,” Inside Higher Ed, August 14, 2024, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/faculty-issues/academic-freedom/2024/08/14/indiana-says-professors-lack-first-amendment-rights. It is difficult to see how this position helps “the institution foster a culture of…free expression…within the institution,” to quote from SB 202. Could Indiana’s attorney general receive tenure at one of its law schools? Perhaps not, especially if he repeated these arguments to his departmental colleagues or advocated for them in the faculty senate.

By and large, the bills introduced have not been carefully crafted. Nor are many consistent with the First Amendment or academic freedom. Instead, they have been sloppy, vague, and often cruel exercises in academic censorship.

And what if, in the future, the state elected a Democratic governor who appointed left-leaning trustees to the state’s various university governing boards? Conservative scholars could suddenly find themselves the primary target of SB 202’s enforcement.

In many ways, SB 202 is the conservative counterpart to the California Community Colleges’ Title 5 “DEIA” Amendment, an unusual liberal educational gag order from 2023.41Michael Hicks, “I’m a Professor. Indiana’s Progressive Colleges Stifle Debate,” Indianapolis Star, February 23, 2024, https://www.indystar.com/story/opinion/columnists/2024/02/23/senate-bill-202-conservatives-left-out-of-indiana-colleges/72705625007/. Under new regulations, the system’s faculty are required, as a condition of tenure, promotion, or retention, to weave an intricately detailed group of “diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility” themes into their teaching and research.42“Final Regulatory Text: Amending Title 5 of the California Code of Regulations, to Include Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility Standards in the Evaluation and Tenure Review of District Employees,” California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office, March 17, 2023, https://www.cccco.edu/-/media/CCCCO-Website/Office-of-General-Counsel/Form-400–Reg-Text-DEIA-Evalution-and-Tenure-Review-of-Dsitrict-Employees.pdf. PEN America came out against these rules at the time, explaining that they threaten “to gag the research and pedagogy of tens of thousands of California community college faculty.”43Jeffrey Adam Sachs and Jeremy C. Young, America’s Censored Classrooms 2023: Lawmakers Shift Strategies as Resistance Rises, (PEN America, November, 2023), https://pen.org/report/americas-censored-classrooms-2023/.

Our position on Indiana’s law is no different. Diversity, whether of viewpoints or anything else, is vital to a university’s health. But the state has no business appointing itself the arbiter of what true intellectual diversity looks like in the college classroom, and no ability to do so without imposing a political agenda on faculty.

Indiana is not alone. Bills like SB 202 became more common this past year. In Arizona, lawmakers proposed legislation to establish a volunteer-run “grade challenge department” at every public university in the state.44Arizona SB 1477, https://legiscan.com/AZ/text/SB1477/2024. Students who believed that they were unfairly graded due to their instructor’s “political bias” would have been able to complain to this department; if they were successful, their instructor would have been required to reevaluate their grade. Oklahoma’s SB 1983 would have given public K–12 students a legally enforceable right to “an unbiased education…that is free from anti-American bias.”45Oklahoma SB 1983, https://legiscan.com/OK/bill/SB1983/2024. And under Ohio’s SB 83, still being considered after its introduction last year, university faculty would be forbidden from “seek[ing] to indoctrinate any social, political, or religious political point of view.” Students who believe that this rule has been violated would have an opportunity to indicate as much on their course evaluations, which in turn would have to be considered by tenure review committees.46Ohio SB 83, https://legiscan.com/OH/bill/SB83/2023. As in Indiana, each of these proposals runs counter to the actual goal of promoting intellectual diversity, and would be ripe for political weaponization and abuse.

The Wrong Way to Combat Antisemitism

Meanwhile, a new—or renewed—genre of educational gag order emerged following the October 7, 2023, attack on Israel by Hamas. As protests swept America’s college campuses, state legislators raced to introduce bills to censor speech they deemed antisemitic.

Such legislation might be permissible or even laudable, provided the speech in question is unprotected by the First Amendment or principles of academic freedom—harassing speech, for example. And given the many incidents of indisputably antisemitic harassment on campuses following the attacks, as well as the corresponding sense of vulnerability among many Jewish students and faculty, a carefully crafted legislative response makes sense.47“Antisemitism on College Campuses: Incident Tracking,” Hillel International, https://www.hillel.org/antisemitism-on-college-campuses-incident-tracking/; Eitan Hersh and Dahlia Lyss, A Year of Campus Conflict and Growth: An Over-Time Study of the Impact of the Israel-Hamas War on U.S. College Students, Jim Joseph Foundation, September 2024, https://jimjosephfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Hersh_Final_Report_Campus_Conflict_and_Growth.pdf. The initial version of Maryland’s HB 1386, which would have mandated training on antisemitism and Islamophobia for university faculty and staff, is one such example.48Maryland HB 1386, https://legiscan.com/MD/text/HB1386/id/2922541. Note that the final bill, which became law, applied only to K–12 schools, not to universities. Similarly, lawmakers could encourage universities to prioritize efforts to support vulnerable students and promote respectful campus dialogue about antisemitism.

But by and large, the bills introduced have not been carefully crafted. Nor are many consistent with the First Amendment or academic freedom. Instead, they have been sloppy, vague, and often cruel exercises in academic censorship.

For instance, at least a dozen states introduced bills in 2024, copied or modified from the Goldwater Institute’s 2016 model legislation, to adopt or expand the use of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s working definition of antisemitism for the purpose of investigating alleged hate crimes, harassment, and discrimination.49Stanley Kurtz, James Manley, and Jonathan Butcher, Campus Free Speech: A Legislative Proposal, Goldwater Institute, 2016, https://www.goldwaterinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Campus-Free-Speech-A-Legislative-Proposal_Web.pdf; “Working Definition of Antisemitism,” International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, https://holocaustremembrance.com/resources/working-definition-antisemitism. These bills would apply across all levels of state government, including at public higher education institutions. Five of these that were proposed in 2024 are now law: Florida’s HB 187, North Carolina’s HB 942, South Carolina’s HB 4042, South Dakota’s HB 1076, and Georgia’s HB 30.50Florida HB 187, https://legiscan.com/FL/text/H0187/id/2945572; North Carolina HB 942, https://legiscan.com/NC/text/H942/id/3013152; South Carolina HB 4042, https://legiscan.com/SC/text/H4042/2023; South Dakota HB 1076, https://legiscan.com/SD/text/HB1076/id/2941107; Georgia HB 30, https://legiscan.com/GA/text/HB30/2023.

Free speech advocates, including PEN America, have long argued that the IHRA’s working definition was never meant to become a binding legal standard, and incorporating it into statute poses a serious threat.51“Wrong Answer: How Good Faith Attempts to Address Free Speech and Anti-Semitism on Campus Could Backfire,” PEN America, November 7, 2017, https://cdn.pen.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/22191637/2017_wrong-answer_11.9.pdf; Kenneth Stern, “I Drafted the Definition of Antisemitism. Rightwing Jews Are Weaponizing It,” Guardian, December 13, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/dec/13/antisemitism-executive-order-trump-chilling-effect. That is primarily because of a series of examples it offers to illustrate what antisemitic speech could, depending on the overall context, look like. These include:

- denying the Jewish people their right to self-determination (e.g., by claiming that the existence of a state of Israel is a racist endeavor);

- applying double standards by requiring of [Israel] a behavior not expected or demanded of any other democratic nation;

- using the symbols and images associated with classic antisemitism (e.g., claims of Jews killing Jesus or blood libel) to characterize Israel or Israelis; and

- drawing comparisons of contemporary Israeli policy to that of the Nazis.

The danger here is easy to see. Statements like the ones listed in the definition might be offensive or inflammatory to some, but on their own, such expressions would undoubtedly be protected by the First Amendment. To cite this definition and list in statute as constituting evidence of illegal harassment or discrimination is a threat both to free speech broadly and, on a college campus, to academic freedom. In fact, the problem is so severe that even Kenneth Stern, the lead author of the IHRA working definition, has called these legislative efforts “a travesty.”52Maggie Hicks, “Colleges Use His Antisemitism Definition to Censor. He Calls It a ‘Travesty,’” Chronicle of Higher Education, March 27, 2024, https://www.chronicle.com/article/colleges-use-his-antisemitism-definition-to-censor-he-calls-it-a-travesty.

And indeed they are. In Florida, which in 2019 enacted the IHRA definition into statute specifically for K–12 and university campuses, the state government has instructed the leaders of its 12 public universities to use the keywords Israel, Israeli, Palestine, Palestinian, Middle East, Zionism, Judaism, Jewish, and Jews to screen course syllabi for “antisemitism or anti-Israeli bias.”53Florida HB 741, https://legiscan.com/FL/text/H0741/id/2004687; Emma Pettit, “Florida’s Public Universities Are Told to Review Courses for ‘Antisemitism or Anti-Israeli Bias,’” Chronicle of Higher Education, August 6, 2024, https://www.chronicle.com/article/floridas-public-universities-are-told-to-review-courses-for-antisemitism-or-anti-israeli-bias. After Texas adopted the IHRA definition on campuses via executive order, an official at the University of Texas–San Antonio, citing the order, told a group of protesters that if they continued to utter the phrase “from the river to the sea,” they would be referred to law enforcement.54Post on X by Adam Steinbaugh, May 17, 2024, https://x.com/adamsteinbaugh/status/1791629429040443442; Isaac Windes, “Pro-Palestine Advocates Get Face Time with UTSA Official as Protests Intensify,” San Antonio Report, May 3, 2024, https://sanantonioreport.org/pro-palestine-advocates-get-face-time-with-utsa-official-as-protests-intensify/.

As these examples make clear, the adoption of the IHRA’s working definition of antisemitism into law risks enabling the chilling and punishment of a wide array of protected speech, infringing on people’s rights. And this risk has been acutely heightened amid the strain of war, where tempers flare and criticism can be directed indiscriminately at a state, government, military, or people.

Not all of the bills described above are educational gag orders under PEN America’s definition. In some cases, while the bills would rewrite state law in ways that invite censorship, they would not all explicitly mandate it. However, other bills introduced after the October attack were straightforward bans on any kind of antisemitic speech, even for instances where no allegation of discrimination or harassment is made and the speech in question is constitutionally protected.

For example, New Jersey’s AB 1288, and the similarly worded SB 3340, would have required (to quote AB 1288) that “an institution of higher education shall not authorize, facilitate, provide funding for, or otherwise support any event or organization promoting antisemitism or hate speech on campus.”55New Jersey AB 1288, https://legiscan.com/NJ/text/A1288/id/2890310; New Jersey SB 3340, https://legiscan.com/NJ/bill/S3340/2024. New York’s AB 8284 would have done something very similar, declaring that “no state aid shall be granted to any college or university that authorizes, facilitates, provides funding for, or otherwise supports any event promoting anti-Semitism on campus.”56New York AB 8284, https://legiscan.com/NY/text/A08284/id/2851640. Finally, Pennsylvania’s HB 2001, along with the initial version of Indiana’s HB 1002, proposed to rewrite state law so that any expression of antisemitism in a college or university, as defined by the IHRA, would have been ipso facto a harassing or discriminatory act.57Pennsylvania HB 2001, https://legiscan.com/PA/text/HB2001/2023; Indiana HB 1002, https://legiscan.com/IN/text/HB1002/2024; Pennsylvania HB 2001, https://legiscan.com/PA/text/HB2001/2023. In effect, faculty and students would have been legally prohibited from, for example, applying “double standards” to Israel—a vague concept that would inevitably chill speech or be used to censor Israel’s critics. Fortunately, none of these bills became law.

Policy Spotlight: Texas’s Executive Order GA-44

On March 27, 2024, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott issued Executive Order GA-44, a confusing policy aimed at combating campus antisemitism.58Texas Executive Order GA-44, https://gov.texas.gov/uploads/files/press/EO-GA-44_antisemitism_in_institutions_of_higher_ed_IMAGE_03-27-2024.pdf. It requires public colleges and universities in the state to do three things:

- Review and update free speech policies to address the sharp rise in antisemitic speech and acts on university campuses and establish appropriate punishments, including expulsion from the institution.

- Ensure that these policies are being enforced on campuses and that groups such as the Palestine Solidarity Committee and Students for Justice in Palestine are disciplined for violating these policies.

- Include the [IHRA] definition of antisemitism…in university free speech policies to guide university personnel and students on what constitutes antisemitic speech.

While it is possible to apply these rules, which are themselves vague and imprecise, in a manner consistent with free expression, that is not the path that Texas has chosen. According to records acquired by the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, multiple state colleges have newly revised their speech policies in blatantly unconstitutional ways.59Dusty R. Johnston to —-, June 12, 2024, https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/25023405/reports-from-texas-universities-and-colleges-to-governor-re-implementation-of-anti-semitism-executive-order.pdf.

For instance, Dallas College students are being warned that any “antisemitism” outdoors or in a common area can lead to expulsion. Howard College’s “Expressive Activities” policy no longer protects “expression that is considered…antisemitism.” At South Texas College, the faculty handbook has been amended to state that “employees or groups engaged in antisemitism shall be disciplined.” And Laredo College’s new “Distribution of Literature” policy forbids faculty from distributing any material that “contain[s]…antisemitism.” In each instance, “antisemitism” is defined using the IHRA working definition.

These policies are not just antithetical to the First Amendment; they endanger education about antisemitism itself. How can a course on the Holocaust proceed if course readings that contain antisemitism are forbidden? Despite its ostensible purpose, if it restricts education about antisemitism, Texas’s executive order may wind up making the problem worse.

Given the censorial ways that Texas colleges are applying Executive Order GA-44, and considering how easily the executive order lends itself to that application, PEN America categorizes it as an educational gag order.

Tactic II: Indirect Censorship

A second tactic embraced by lawmakers seeking to censor higher education in 2024 was a continuation of an approach begun the previous year: legislation that technically leaves faculty speech untouched, but instead undermines the university structures that make academic freedom possible, placing university administrators and governing bodies under the direct ideological control of the government. This approach has steadily grown in popularity among lawmakers. In fact, the number of such bills proposed in 2024 exceeded the number of direct higher education gag orders for the first time since PEN America began keeping track.

To be sure, governments have a legitimate oversight role over public universities regarding topics such as budgets, completion rates, job preparedness, and relationships with the community. But when it comes to imposing ideological dictates on the ways universities are run, governments risk knocking the support beams out from under academic freedom and campus free expression.

In America’s Censored Classrooms 2023, PEN America first outlined the emergence of legislation that imposes such dictates on universities:

Academic freedom and campus free speech have many defenders… Tenure protections, enshrined in collective agreements and defended by faculty unions, ensure that faculty cannot be disciplined or dismissed for political reasons. Accreditation bodies can downgrade or decertify institutions that repeatedly violate academic freedom, costing these institutions millions of dollars in federal funds. Principles of shared governance, such as the 1966 American Association of University Professors (AAUP) Statement on Government of Colleges and Universities, ensure that “the faculty has primary responsibility for such fundamental areas as curriculum, subject matter and methods of instruction, research, faculty status, and those aspects of student life which relate to the educational process.”

And long-standing norms around institutional autonomy insulate public higher education institutions from undue political interference, enabling them to craft their own mission statements and make their own programmatic decisions, and preserving them as spaces where ideas both popular and unpopular can be discussed, studied, and learned from… Together, these defenses function as a kind of academic immune system, shielding individual faculty from censorship. It is this system on which educational gag order supporters are now training their fire.60Jeffrey Adam Sachs and Jeremy C. Young, America’s Censored Classrooms 2023: Lawmakers Shift Strategies as Resistance Rises (PEN America, November 2023), https://pen.org/report/americas-censored-classrooms-2023/.

Bills undermining this support structure continued to increase in frequency in 2024. Popular types included bills to limit or abolish faculty tenure, erode shared governance, and restrict university leadership from discussing certain topics. Many bills contained provisions that restrict several of these targets at once. Taken as a whole, lawmakers displayed new creativity in attacking this academic freedom support structure.

DEI Restrictions

Efforts to ban and restrict diversity work in universities began with the Trump administration’s Executive Order 13950 in September 2020. But after years of efforts aimed largely at educational speech, course assignments, and book bans, the 2023 and 2024 legislative sessions saw a rash of official government actions against DEI writ large as a field of practice, culminating with a series of official bans of DEI in higher education.

PEN America defines a DEI restriction as a bill or executive order that prohibits colleges and universities from establishing or maintaining an administrative office charged with promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion, or that prohibits DEI-related public or student programming on campus. The specific language varies from bill to bill, but typically DEI restrictions make a point of excluding academic courses, student supervision, and other purely academic, faculty- or student-led spaces from these legislated prohibitions.

This means that a common feature of DEI restrictions is that they do not technically censor educational speech by faculty. This fact has made them more popular with lawmakers and less vulnerable to litigation on First Amendment grounds. Yes, they restrict speech on campus, but not speech by educators or students or in the classroom. Academic freedom remains intact. At least in theory.

In practice, though, something much more sinister tends to happen.

Sixteen state-level DEI restriction bills were proposed in 2024, of which three became law: Iowa’s SF 2435, Utah’s HB 261, and Alabama’s SB 129 (which does not ban DEI offices completely, but does restrict some of their functions).61Alabama SB 129, https://legiscan.com/AL/text/SB129/2024; Iowa SF 2435, https://legiscan.com/IA/text/SF2435/2023; Utah HB 261, https://legiscan.com/UT/text/HB0261/2024.

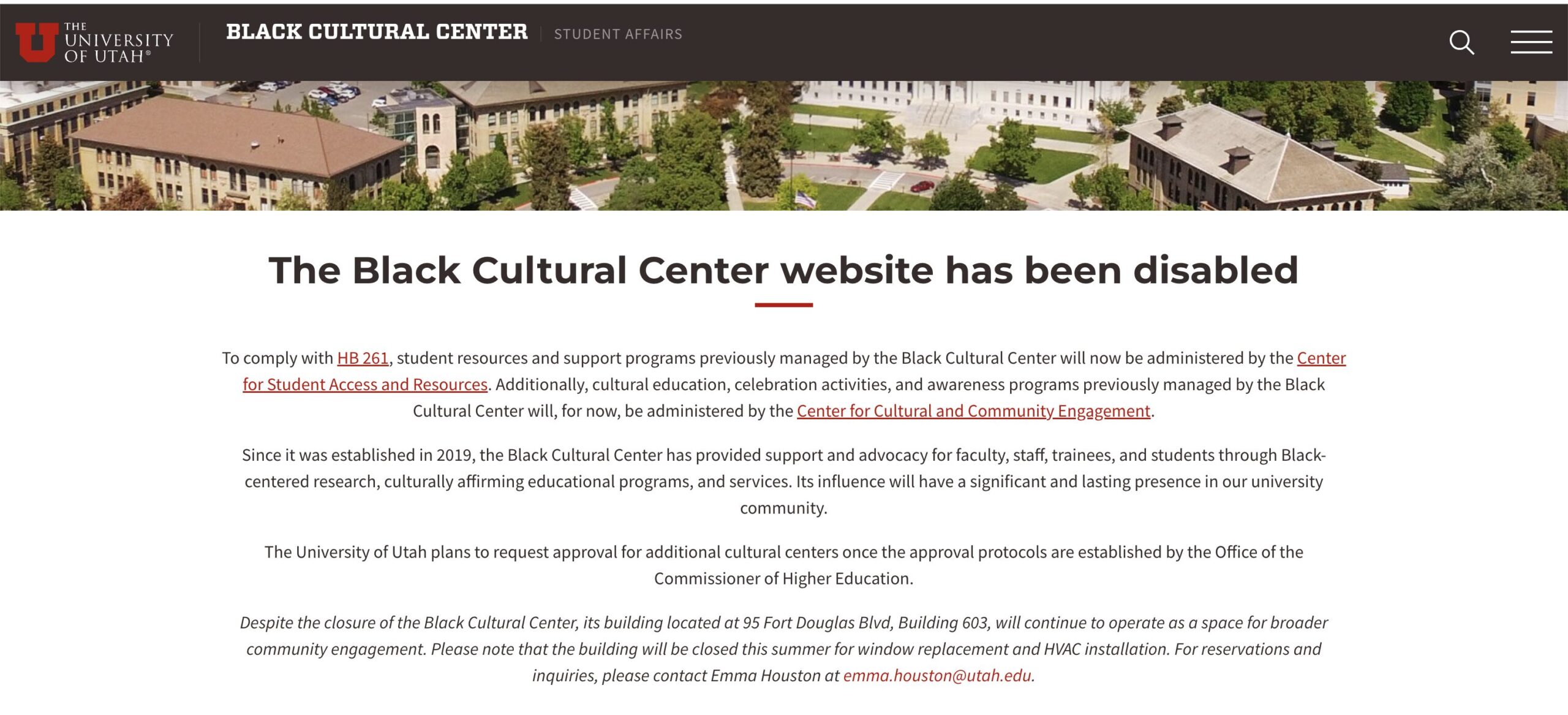

Each of these laws purports to strike a balance between banning DEI offices (which the legislators accuse of bias) and respecting academic freedom. In March 2024, the journalist Conor Friedersdorf singled out Utah’s HB 261 for special praise.62Conor Friedersdorf, “The State That’s Trying to Rein In DEI Without Becoming Florida,” Atlantic, March 31, 2024, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2024/03/utah-anti-dei-law-higher-education/677928/. He called it a “worthy experiment” and wrote that it bans DEI outside the classroom while also “trying to protect academic freedom with carve-outs for research and course teaching.” He also claimed that the law makes “real compromises with DEI supporters” and predicted that institutions like the Black Cultural Center at the University of Utah would remain open.

Unfortunately, that is not how it worked out. In the months after HB 261 became law, public colleges and universities across Utah scrambled to put the law’s vague language into practice, resulting in rules that infringe on core educational speech.

For example, Utah Tech University is warning faculty to “avoid using any of the terms ‘diversity,’ ‘equity,’ or ‘inclusion’ individually in connection with any policy, procedure, practice, program, office, initiative, required training, or with titles of other committees, activities, or interview questions.”63“House Bill 261 & 257 FAQs and Guidance,” Utah Tech University, https://utahtech.edu/hb261/. Southern Utah University also forbids “any combination” of those terms by academic departments or programs.64“Legislative Update: Frequently Asked Questions,” Southern Utah University, https://www.suu.edu/legislative-update/faq.html. How faculty are expected to self-edit in this fashion—the words “diversity” and “inclusion” at least being fairly common in the English language—is unclear, but the state higher education system has established a hotline for reporting violations.65Jonathon Sharp, “Utah Launches New Hotline for Violations of DEI law,” ABC 4, June 10, 2024, https://www.abc4.com/news/politics/utah-launches-new-hotline-for-violations-of-dei-law/. Utah Tech also tells faculty that any grant application containing a DEI concept (for instance, one that “asserts that socio-political structures are inherently a series of power relationships and struggles among racial groups”) will now require approval from the board of trustees.66“House Bill 261 & 257 FAQs and Guidance,” Utah Tech University, https://utahtech.edu/hb261/. And at the University of Utah, faculty are now prohibited from mentioning their own commitment to or understanding of DEI on course syllabi.67“FAQ: Faculty EDI Guidance,” University of Utah, https://attheu.utah.edu/facultystaff/frequently-asked-questions-faculty-edi-guidance/.

And the Black Cultural Center at the University of Utah? It no longer exists.68Johanna Alonso, “DEI Ban Prompts Utah Colleges to Close Cultural Centers, Too,” Inside Higher Ed, July 1, 2024, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/diversity/2024/07/01/onset-anti-dei-law-utah-colleges-close-cultural-centers. Its website has been dismantled, and the resources it once offered students have been assigned elsewhere. This is part of a widespread post-HB 261 trend in Utah, one that has seen the forced closure of dozens of university cultural centers serving Black, women, LGBTQ+, Native American, and many other kinds of students.69Jeremy C. Young, “Farewell to the Cultural Center?,” Inside Higher Ed, August 7, 2024, https://www.insidehighered.com/opinion/views/2024/08/07/closing-cultural-centers-sends-clear-message-opinion; Courtney Tanner, “Utah Anti-DEI Law Doesn’t Require Cultural Centers to Close. But Higher Ed. Commissioner Says It’ll Be Inevitable,” Salt Lake Tribune, June 27, 2024, https://www.sltrib.com/news/education/2024/06/27/utah-higher-ed-commissioner-says/. Similar closures have occurred in every state that has passed DEI restrictions, including Florida, where the University of North Florida responded to a new anti-DEI law there by closing its interfaith center.70Dennis Holtschneider, “How a Campus Interfaith Center Fell to Florida’s Anti-DEI Legislation,” Religion News Service, February 27, 2024, https://religionnews.com/2024/02/27/how-a-campus-interfaith-center-fell-to-floridas-anti-dei-legislation/.

Texas offers another illustrative example. Lawmakers there also promised that their DEI ban, SB 17, would not threaten faculty speech. Yet shortly after it came into effect in 2024, it was cited by UT Austin’s legal team when the university canceled a former faculty member’s lecture on the experience of queer students.71Lauren Gutterman and Lisa L. Moore, “Academic Freedom in the Wake of SB 17,” Academe Blog, March 25, 2024, https://academeblog.org/2024/03/25/academic-freedom-in-the-wake-of-sb-17/. Around the same time, the University of Houston blocked a student from organizing LGBTQ+ events on campus, also on the grounds of SB 17.72Erin Gretzinger and Maggie Hicks, “The Chaos of Compliance,” Chronicle of Higher Education, March 22, 2024, https://www.chronicle.com/article/the-chaos-of-compliance. And during testimony this past spring before the Texas state senate, the University of Texas System’s general counsel warned that SB 17 was wreaking havoc with faculty members’ ability to apply for federal research grants, many of which require diversity statements and DEI work as part of the application package.73Lily Kepner, “Texas Senate Panel Holds Hearing on DEI, Antisemitism. What UT Chancellor Said of Protests,” Austin American-Statesman, May 15, 2024, https://www.statesman.com/story/news/education/2024/05/15/texas-sb17-anti-dei-compliance-free-speech-antisemitism-at-universities/73677079007/; Becky Fogel, “Are Public Universities Doing Enough to Comply with Texas’ DEI Ban? Lawmakers Will Decide,” KUT News, May 14, 2024, https://www.kut.org/education/2024-05-14/are-public-universities-doing-enough-to-comply-with-texas-dei-ban-lawmakers-will-decide.

As these examples in Utah, Florida, and Texas demonstrate, it has thus far proven functionally impossible for a legislature to craft a DEI ban that does not undermine, restrict, or weaken academic freedom or campus free speech. Indeed, in some cases, that may be the point. At the end of the day, such bans either directly restrict some aspects of academic freedom or create such a broad chilling effect that administrators feel compelled to implement such restrictions on their own. And in places where DEI offices or initiatives work to incorporate viewpoints across the ideological spectrum, conservative, religious, or other heterodox voices may join the list of casualties of these bans. Ultimately, a legislature cannot ban some ideas on campus without chilling and silencing all ideas there.

It has thus far proven functionally impossible for a legislature to craft a DEI ban that does not undermine, restrict, or weaken academic freedom or campus free speech. Indeed, in some cases, that may be the point.

Mandatory Institutional Neutrality Bills

A related threat to the support structure for academic freedom—often found in the same legislation as DEI restrictions—is language mandating institutional neutrality. Bills with these provisions impose neutrality on university administrations, barring institutional leadership (and sometimes subsidiary units like academic departments) from taking public positions on certain issues. Once again, lawmakers often promise that their bills will leave faculty speech untouched. Once again, the facts say otherwise.

Seven bills mandating some form of institutional neutrality were introduced in 2024, and an eighth that was proposed in the previous legislative session continued to advance. Three became law: Indiana’s SB 202, Iowa’s SF 2435, and Utah’s HB 261.74Indiana SB 202, https://legiscan.com/IN/text/SB0202/2024; Iowa SF 2435, https://legiscan.com/IA/text/SF2435/id/2988266; Utah HB 261, https://legiscan.com/UT/text/HB0261/id/2907864.

Some mandatory neutrality policies are relatively vague, an approach that comes with its own problems. For instance, a Florida Board of Governors policy, adopted in January based on the state’s SB 266 law from 2023, banned funding for campus activities “intended to achieve a desired result” on “topics that polarize or divide society among political, ideological, moral, or religious beliefs, positions, or norms.”75Florida Reg. 9.016 Prohibited Expenditures, https://www.flbog.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Draft-Regulation-9.016.pdf. With the board of governors set to determine what activities or topics meet this test, the regulation amounts to the board giving itself a license to censor any university statement it pleases.

But the new bills that became law in 2024, and many that were proposed, were much more specific in their prohibitions.

Iowa’s SF 2435, for instance, was signed by Gov. Kim Reynolds in May.76Iowa SF 2435, https://legiscan.com/IA/text/SF2435/id/2988266. Following model legislation developed by the Manhattan Institute, it prohibits public colleges and universities from promoting as their official position “a particular, widely contested opinion referencing unconscious or implicit bias, cultural appropriation, allyship, transgender ideology, microaggressions, group marginalization, antiracism, systemic oppression, social justice, intersectionality, neo-pronouns, heteronormativity, disparate impact, gender theory, racial privilege, sexual privilege, or any related formulation of these concepts.”77Christopher F. Rufo, Ilya Shapiro, and Matt Beienburg, “Abolish DEI Bureaucracies and Restore Colorblind Equality in Public Universities,” Manhattan Institute, January 18, 2023, https://manhattan.institute/article/abolish-dei-bureaucracies-and-restore-colorblind-equality-in-public-universities. Given the vagueness implied by that last phrase, virtually any idea whatsoever could be considered forbidden for a university to express.

Similar lists can be found in failed bills such as West Virginia’s HB 4387, Arizona’s SB 1005, South Carolina’s HB 4290, Iowa’s HF 616, and Nebraska’s LB 1330.78West Virginia HB 4387, https://legiscan.com/WV/text/HB4387/id/2879332; Arizona SB 1005, https://legiscan.com/AZ/text/SB1005/id/2913983; South Carolina HB 4290, https://legiscan.com/SC/text/H4290/id/2801960; Iowa HF 616, https://legiscan.com/IA/text/HF616/id/2726637; Iowa SF 2435, https://legiscan.com/IA/text/SF2435/id/2988266; Nebraska LB 1330, https://legiscan.com/NE/text/LB1330/id/2886611/Nebraska-2023-LB1330-Introduced.pdf. The list of proscribed concepts in Utah’s HB 261, now law, is somewhat abbreviated by comparison, but no less alarming for it; for instance, one of the concepts on which Utah universities must remain neutral is “bias” itself.79Utah HB 261, https://legiscan.com/UT/text/HB0261/id/2907864.

Again, these bills were and are being marketed to the public as compatible with academic freedom for faculty. In practice, however, the pitfalls are countless. Already in Utah, HB 261 is causing chaos. Administrators at Salt Lake Community College are warning faculty to avoid expressing their own personal viewpoints on topics like structural racism and social justice from a college email account or while “wearing SLCC-branded clothing.”80“HB 261 and HB 257 Frequently Asked Questions,” Salt Lake Community College, https://www.slcc.edu/about/faq-hbs.aspx. The University of North Carolina System, which adopted an institutional neutrality policy in 2024, is now telling “university-fostered” student groups not to “stray into political or social advocacy or commentary.”81“Guidance Regarding Implementation of Equality Policy,” University of North Carolina System, June 28, 2024, https://www.northcarolina.edu/wp-content/uploads/reports-and-documents/legal/unc-system-guidance-implementation-of-equality-policy-june-2024.pdf.

University leaders should not have to consider whether they are breaking the law—for example, whether their official expression of sympathy (allowed) crosses the line into endorsing “allyship” (forbidden). Nor should they have to fear that their policy of encouraging civil discourse (legal) will be misconstrued as promoting “inclusive language” (illegal).

And even if universities are successful in confining the effects of these laws to purely institutional speech—say, an official university web page—very little is actually settled. What about a university president who acknowledges Pride Month, a provost who denounces campus racism, a Jewish studies department that condemns antisemitism, or an office that seeks to combat bias on campus? Is any of that permissible when taking an official position on “gender identity,” “antiracism,” “social justice,” “group marginalization,” and “bias” are off the table? Would any campus leader be willing to risk a lawsuit, loss of state funding, or their job in order to find out?

PEN America does not oppose institutional neutrality policies in higher education, but we believe that colleges and universities should choose for themselves—and in consultation with faculty, staff, and students—whether to adopt such policies, what they should encompass, and how they should be implemented. After all, there are many occasions when university leaders actually have a legitimate need to express their values—in the wake of a campus incident, to confer an honorary degree, to promote faculty scholarship, or to inaugurate some new research center focused on a pressing social issue.

These are challenging questions that require nuance and care on the part of administrators, as both proponents and opponents of institutional neutrality have noted.82Harry Kalven Jr. et al., Report on the University’s Role in Political and Social Action, University of Chicago, November 11, 1967, https://provost.uchicago.edu/sites/default/files/documents/reports/KalvenRprt_0.pdf; William G. Bowen, Lessons Learned: Reflections of a University President (Princeton University Press, 2010). But at times like these, university leaders should not have to consider whether they are breaking the law—for example, whether their official expression of sympathy (allowed) crosses the line into endorsing “allyship” (forbidden). Nor should they have to fear that their policy of encouraging civil discourse (legal) will be misconstrued as promoting “inclusive language” (illegal).

Shared Governance Restrictions and Other Attacks on Higher Ed Autonomy

Several other types of bills aiming to undermine the autonomy of higher education institutions advanced in 2024. Among them were three bills that would have restricted or eliminated faculty tenure, seven that would have interfered with faculty members’ control of the curriculum, four that would have eroded shared governance by shifting to administrators duties that were long held by faculty, and one affecting university accreditation. Of these, three became law: Indiana’s SB 202 (anti-tenure), Alabama’s SB 129 (curricular control), and Tennessee’s SB 2528 (accreditation).83Indiana SB 202, https://legiscan.com/IN/bill/SB0202/2024; Alabama SB 129, https://legiscan.com/AL/text/SB129/2024; Florida HB 1291, https://legiscan.com/FL/text/H1291/id/2953485; Tennessee SB 2528, https://legiscan.com/TN/text/SB2528/id/2996201; Utah SB 192, https://legiscan.com/UT/text/SB0192/id/2961483. Note that the Indiana and Alabama laws also have other censorial features.

In America’s Censored Classrooms 2023, PEN America explained why attacks on faculty tenure, curricular control, and accreditation undermine the support structure for academic freedom.84Jeffrey Adam Sachs and Jeremy C. Young, America’s Censored Classrooms 2023: Lawmakers Shift Strategies as Resistance Rises (PEN America, November 2023), https://pen.org/report/americas-censored-classrooms-2023/. For this year’s report, we are adding a new category of legislation with major implications for this support structure: shared governance restrictions. These are bills that restrict or extinguish the power of faculty to shape the policies and practices at their institutions.

Shared governance is a core principle of American academia and a bulwark of academic freedom. As far back as 1966, the American Association of University Professors, the American Council on Education, and the American Association of Colleges and Universities linked shared governance to the expressive freedoms of faculty and students.85“Statement on Government of Colleges and Universities,” American Association of University Professors, https://www.aaup.org/report/statement-government-colleges-and-universities. According to these groups, “The faculty has primary responsibility for such fundamental areas as curriculum, subject matter and methods of instruction, research, faculty status, and those aspects of student life which relate to the educational process” —along with a right to consultation in virtually every other aspect of university life. It must be faculty and not administrators who decide whether a professor’s grant application is worthy of funding, whether a new course should be approved, and whether a student is qualified to enter an academic program or merits a degree.

This faculty control is what shared governance restrictions try to stop—ever since the first shared governance restriction, a bill championed by Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker and signed into law in 2015.86Timothy V. Kaufman-Osborn, “The Downfall of Shared Governance at Wisconsin,” Academe, January–February 2017, https://www.aaup.org/article/downfall-shared-governance-wisconsin. In 2024, bills of this type made a significant comeback.

For example, Arizona’s HB 2735 passed both chambers of the legislature before being vetoed by Gov. Katie Hobbs.87Arizona HB 2735, https://legiscan.com/AZ/text/HB2735/id/2938842. Had it become law, it would have demoted university faculty senates to an advisory role and concentrated all authority over program creation and degree approval in the hands of the president. Arizona’s similarly unsuccessful SB 1477, mentioned earlier in this report, would have given a panel of ordinary citizens appointed by the Board of Regents the authority to review grades for “political bias.”88Arizona SB 1477, https://legiscan.com/AZ/text/SB1477/2024. Iowa’s HF 2558, which cleared the state house before dying in a senate subcommittee, would have prohibited “any faculty senate committee or subcommittee from having any governance authority over the institution.”89Iowa HF 2558, https://legiscan.com/IA/text/HF2558/id/2946621/Iowa-2023-HF2558-Amended.html. And Utah’s failed SB 226, a copy of the model “General Education Act” written by staff at several conservative think tanks, would effectively have granted college presidents unlimited power to close programs they disliked, forcing tenure-track faculty members in those programs to reapply for their jobs in a new “School of General Education” with a fixed curriculum and no system of faculty governance or tenure.90Utah SB 226, https://legiscan.com/UT/text/SB0226/id/2921844; John K. Wilson, “The Right-Wing Attack on Academia, With a Totalitarian Twist,” Inside Higher Ed, November 16, 2023, https://www.insidehighered.com/opinion/views/2023/11/16/new-front-right-wing-attack-academia-opinion.

When attacks on shared governance arise from college and university leadership, and especially when they come from lawmakers, they are a threat to the support structure for academic freedom.