Hard News

Journalists and the Threat of Disinformation

PEN America’s nationwide survey of more than 1,000 reporters and editors on how disinformation is disrupting the practice of journalism

Responses from more than 1,000 U.S. journalists reveal that disinformation is significantly changing the practice of journalism, disrupting newsroom processes, draining the attention of editors and reporters, demanding new procedures and skills, jeopardizing community trust in journalism, and diminishing journalists’ professional, emotional, and physical security.

Introduction and Key Findings

Professional journalists, editors, and news organizations that provide credible reporting and promote informed civic engagement stand as a bulwark against the onslaught of disinformation being injected into public discourse. It is from their newspapers, websites, and broadcasters that communities can expect to access reliable information and understand the debates that shape their societies. Journalists have long been tasked with holding public officials to account, thwarting obfuscation by those with political or economic power, and probing for the facts. Never before, however, have they had to do so in the face of such an extreme surge of falsehoods and manipulations supercharged by algorithms and nefarious actors, and at a time when their news outlets are struggling for survival with starkly depleted resources.

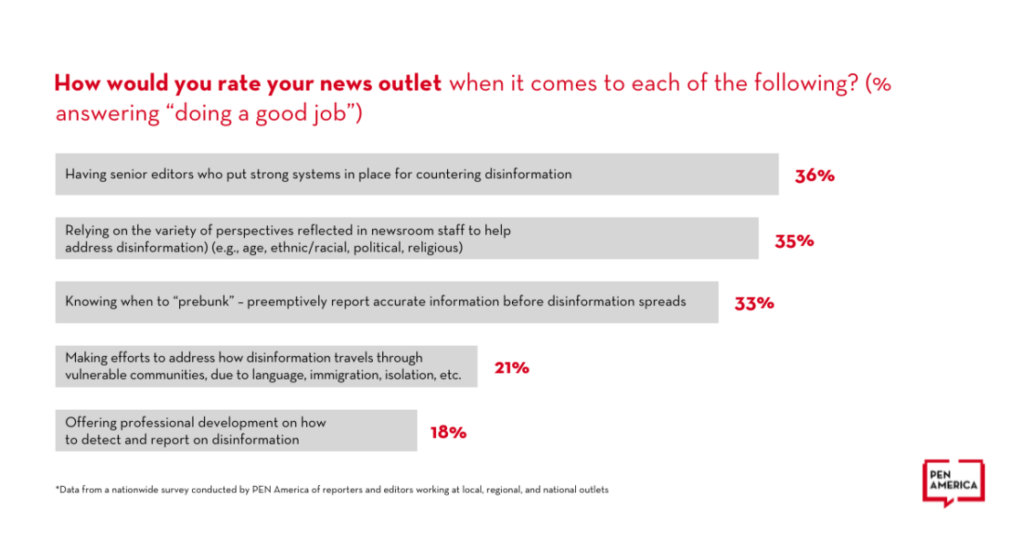

In a nationwide survey, PEN America asked reporters and editors from local, regional, and national outlets how working amid floods of disinformation—content created or distributed with intent to deceive—is altering their profession, their relationships with their sources and audiences, and their lives. Responses from more than 1,000 U.S. journalists1For the purposes of this survey, professional journalists are defined as those who adhere to a set of editorial standards, ethics, and practices. This does not include bloggers or citizen journalists. Similarly, their news outlets exemplify the values and tenets of credible news gathering and dissemination including transparency, accountability, inclusivity, and accuracy. reveal that disinformation is significantly changing the practice of journalism, disrupting newsroom processes, draining the attention of editors and reporters, demanding new procedures and skills, jeopardizing community trust in journalism, and diminishing journalists’ professional, emotional, and physical security. Journalists told PEN America how worried they are about the impact of disinformation on their work, the time and effort it takes to keep from inadvertently spreading falsehoods—and how underequipped they and their newsrooms are to effectively counter the torrents of untruths that threaten a free press’s critical role in our democratic process. Only 18 percent of the reporters and editors responding said they were being offered sufficient professional development support on how to detect and report on disinformation.

Key findings:

- Virtually all the journalists responding consider disinformation a serious problem for journalism today; 81 percent say it’s a very serious problem.

- Most deal with disinformation regularly: 61 percent on some days and 15 percent all or most days.

- Only 8 percent say that detecting and addressing disinformation is “not too important” a priority at their news outlet; 40 percent categorized this task as “urgent.”

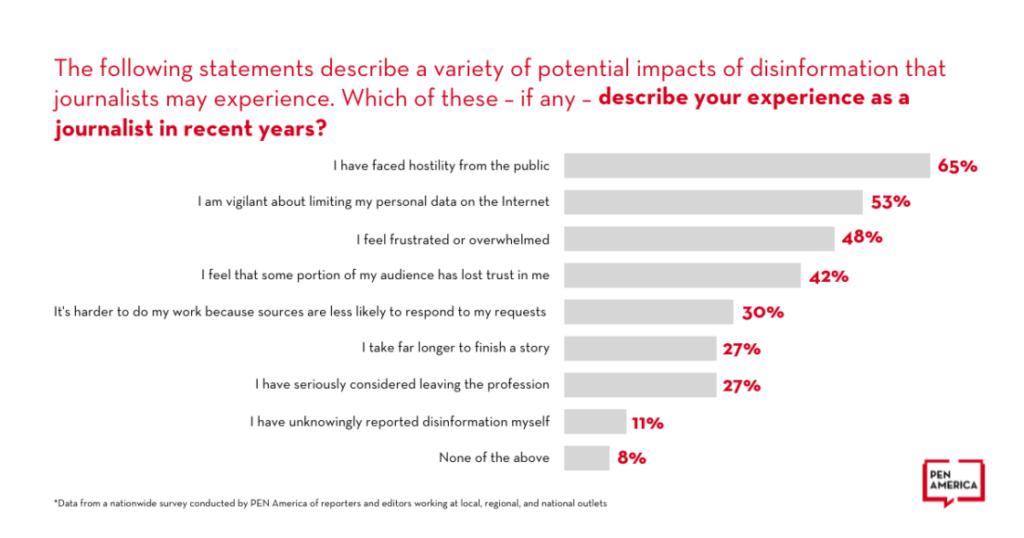

- More than 90 percent said disinformation had an impact on their experiences as journalists in recent years; 65 percent had faced hostility from the public, 48 percent reported feeling frustrated or overwhelmed, and 42 percent felt some portion of their audience had lost trust in them.

- While 99 percent of the journalists expressed at least some confidence in their own ability to detect disinformation as they worked, 11 percent acknowledged they had unwittingly reported disinformation themselves.

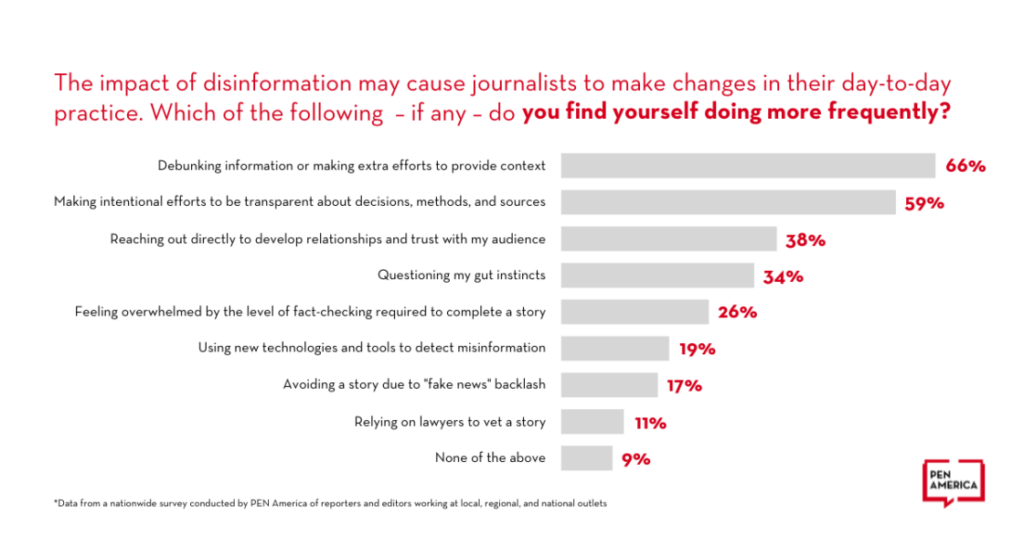

- More than 90 percent had made one or more changes in their journalistic practice as a result of disinformation, including 66 percent who said they are spending more time actively debunking disinformation and 59 percent who reported intentional efforts to be transparent about decisions, methods, and sources. But one in three found themselves questioning their gut instincts and one in four reported feeling overwhelmed by the level of fact-checking required to complete a story. And 17 percent said they had avoided doing a story they were considering covering due to fear of “fake news” backlash that would seek to discredit their accurate reporting.

- Three out of five journalists surveyed said that amid the proliferation of disinformation and distrust, at least one of these things had happened to them: received threatening emails, phone calls, or letters; been harassed in person while working; been doxed or trolled; been catfished; and/or feared for their personal safety sufficiently to add security precautions to their daily routines.

Yet despite these high levels of concern and clear impact on their practices, most journalists responding said they did not feel they had the specialized skills or the newsroom support systems to respond adequately to the disinformation crisis:

- Only 30 percent of the journalists said their news outlet had generally effective processes in place to cope with disinformation; 40 percent said no organization-wide approach exists.

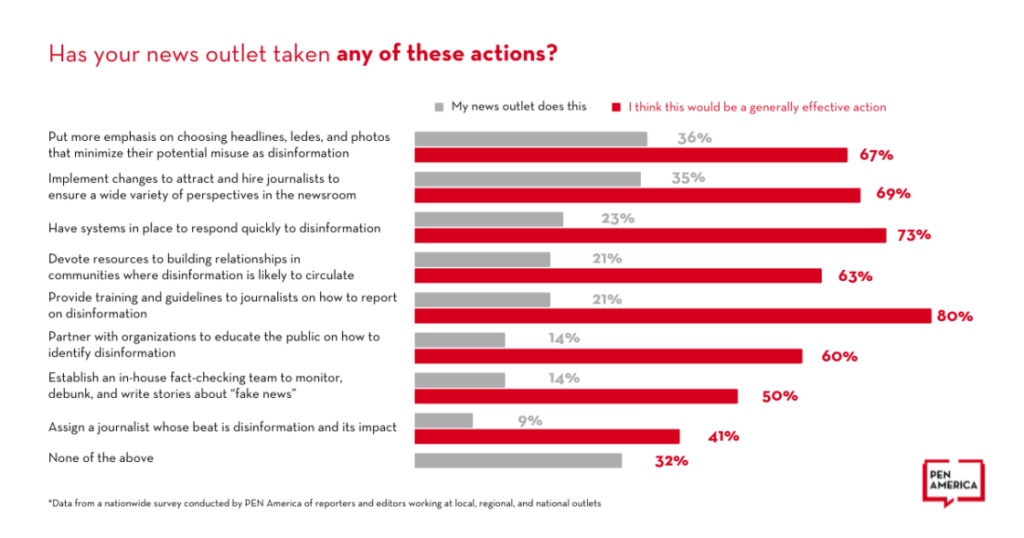

- Asked about eight different steps media outlets could take to address disinformation—including training journalists in how to report on it and putting systems in place to respond to it quickly—one in three said their newsroom has not taken a single one.

We’re in the business of telling truth to the world … This disinformation epidemic … has very much undermined people’s faith in the media, but also faith in reality in a lot of ways, which creates the conditions for actual authoritarianism and fascism, which is the ultimate threat here. And the first thing that happens when an authoritarian with real power comes along is they get rid of the free press.

Luke O’Brien, Journalist & Researcher

Disinformation in the Context of Free Expression and Press Freedom

PEN America understands disinformation as a fundamental threat to free expression. The PEN Charter, framed in 1948, commits to fighting “mendacious publication, deliberate falsehood and distortion of facts for political and personal ends.” PEN America has taken up this urgent issue as a core part of our work, beginning in 2017 with the publication of our report Faking News: Fraudulent News and the Fight for Truth, in which we anticipated the potential risks if disinformation went unchecked, including “unending political polarization and gridlock; the undermining of the news media as a force for government accountability; a long-term risk to the viability of serious news; an inability to devise and implement fact- and evidence-driven policies; the vulnerability of public discourse to manipulation by private and foreign interests; an increased risk of panic and irrational behavior among citizens and leaders; and government overreach, unfettered by a discredited news media and detached citizenry.” Today we see a deluge of falsehoods, in words and images, injected into the public conversation in deliberate campaigns by operatives who seek political, financial, or societal advantage. Disinformation impedes the public’s access to the accurate information needed for civic engagement and informed decision-making. It undermines our public discourse, sows discord, and weakens our political system and ultimately our democracy upon which free expression rights rest. The potency of this threat is evident in how disinformation has baselessly diminished faith in our election system, cost lives by undermining the public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and fueled an insurrection at the Capitol that was intended to disrupt the peaceful transition of power.

A free press is a fundamental manifestation of free expression, and purveyors of disinformation expressly target that role. From doctored photos to planted rumors to lies in letters to the editor to misleading claims and conspiratorial narratives reshared across social media, journalists are bombarded by deceptions whether reporting on local politics or wars abroad. The deliberate spread of falsehoods pollutes the information space, planting doubt and making it hard for people to discern the veracity of news sources and to tell fact from falsehood. False claims of “fake news” directed at credible journalists and their outlets further confuse the public. Studies show that the distrust that should be directed at sources of disinformation is often instead projected onto reputable news sources.2A Harvard University study, for example, found that increased exposure to “fake news” was associated with a decline in mainstream media trust among respondents. This not only diminishes the uptake of accurate information and undercuts the public’s shared sense of truth, but it slices into support for the role of and trust in a free press more broadly. As such, disinformation should be treated as any other attack on the press that impedes the ability to fact gather, jeopardizes the validity of reporting, and slanders media professionalism. “It is an existential threat to our entire profession,” said Luke O’Brien, a journalist who has reported widely on disinformation and extremism and as a research fellow at the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School. “We’re in the business of telling truth to the world . . . This disinformation epidemic . . . has very much undermined people’s faith in the media, but also faith in reality in a lot of ways, which creates the conditions for actual authoritarianism and fascism, which is the ultimate threat here. And the first thing that happens when an authoritarian with real power comes along is they get rid of the free press.”

The PEN America survey seeks to explicate how reporters and editors are experiencing and responding to this disinformation crisis, including the impact it is having on their news organizations and their profession and how they are changing their practices in response. The independent, nonpartisan FDR Group conducted this research on behalf of PEN America during the second half of 2021.3PEN America commissioned the independent, nonpartisan research organization FDR Group to prepare and conduct the survey. To inform the themes and questions to cover in the survey, two virtual focus groups were conducted with journalists from across the country in April 2021. The survey instrument crafted by the FDR Group, with input from PEN America, was pretested with journalists to ensure that question wording was accessible and appropriate. Questions were randomized and answer categories rotated in an effort to minimize non-sampling sources of error. In total, the survey included 45 items: 33 were substantive and 12 were demographic; on average it took about 10 minutes to complete. In addition, an open-ended opportunity was provided for respondents to share ideas for improving how journalists can effectively counter disinformation or to elaborate on any of their responses.

Survey Monkey was used to administer the questionnaire and collect the data. For the fielding of the survey, an initial invitation plus one reminder were sent via email on a rolling basis starting during the second half of 2021 to a total of 22,405 journalists listed in the comprehensive database maintained by an online media marketing company. The criteria used to define journalists were that they must be based in the U.S.; serving in editing and reporting roles; and working at print, online-only, or broadcast (radio and TV) news outlets with local, regional, or national reach. The email message, which included a description of the purpose of the research, assurances of anonymity, and a link to the online survey, was sent from Suzanne Nossel, chief executive officer of PEN America. This outreach generated 857 completed surveys. At the same time, PEN America staff reached out to its own networks of journalists and nonprofit organizations that serve journalists to encourage participation in the online survey. This outreach resulted in 173 completed surveys. An analysis of the two sample sources showed no discernible differences in attitudes and experiences.

The anonymous comments included in this report are drawn from the responses to the open-ended question in the survey. Interviews with journalists and other experts in disinformation identified by name in the report were conducted to augment and contextualize the findings. The online questionnaire, which was informed by a series of focus groups with media professionals, was distributed to U.S.-based reporters and editors working for newspapers, broadcasters, and online news organizations serving community, regional, and national audiences. The survey sample was drawn primarily from news organizations registered by a media-monitoring platform that serves public relations and marketing companies; it also included PEN America’s constituency of journalist members and contacts. Anonymity was guaranteed by the survey methodology, and an open-ended opportunity for comments was provided. Responses were received from 1,030 journalists, of whom:

- 56 percent worked for newspapers and/or magazines, 22 percent for online-only outlets, and 13 percent for TV or radio stations; 22 percent characterized their news organization as a nonprofit.

- 41 percent described themselves as staff reporters, 31 percent as editors, 10 percent as freelance, 6 percent as news executives, 5 percent as opinion writers, and the remainder as producers, video/audio/photo journalists, or “other.”

- 76 percent identified as white, 15 percent as a person of color, and the remaining chose “something else” or did not respond.

- 52 percent said they had 20 or more years of experience; 7 percent said they had 4 years or less.

- 42 percent said their news outlet had fewer than 20 journalists, 16 percent 20–49 journalists, 14 percent 50–99 journalists, 19 percent 100 or more, and the rest did not specify.

Analysis of the survey responses shows that the impact of disinformation on journalists and their news organizations tracks closely with other trends that PEN America has identified as major threats to freedom of expression and its underpinning role for a democratic, equitable, and inclusive society. These include:

- The surge in online abuse. Journalists who report on disinformation or attempt to counteract it are often the targets of harassment campaigns intended to undermine their integrity and intimidate them into self-censorship. Of the survey respondents, 58 percent said they were subjected to one or more forms of abuse, much of which occurs online including threatening emails, trolling, doxing, or “catfishing” by a real person using a fake identity. As PEN America has detailed in its report No Excuse for Abuse and other research on this issue, because writers and journalists conduct so much of their work online and in public, they are especially susceptible to such harassment—and within these professions, the most targeted are those who identify as women, BIPOC, LGBTQIA+, and/or members of religious or ethnic minorities. Journalists have a high degree of dependence on Twitter, Facebook, and other social media platforms to follow breaking news, connect with sources, and draw attention to their work. This visibility can make them targets, especially when they attempt to debunk purveyors of disinformation who themselves are operating online. PEN America has developed an Online Abuse Defense Training Program specifically designed for newsrooms seeking to develop policies, protocols, and resources to better protect and support journalists facing harassment online.

- The crisis in local news coverage. The radical decline in local news outlets providing community level coverage has a documented impact on access to trusted information sources. As described in PEN America’s report, Losing the News: The Decimation of Local News and the Search for Solutions, the upending of the business model for the news industry by the shift of advertising to digital platforms has led to the shuttering of hundreds of newspapers and mass layoffs of reporters and newsroom staff at those that remain. Smaller-market TV and radio stations are affected alongside newspapers as hedge funds and media conglomerates buy up outlets and subject them to ongoing cost-cutting to retain profit margins for investors. With the loss of local news coverage, communities are less likely to be politically informed, to be civically engaged, to see their government officials held to account, or to be able to access critical information—for example, on the COVID-19 pandemic—shared by familiar and culturally attuned sources they have reason to trust. This has created an information vacuum at the same time as disinformation is spreading rapidly, and left even fewer journalists working with ever diminished resources positioned to counter it. As one community-based reporter said, “There are a lot of ways to combat disinformation—such as assigning special beats, hiring extra reporters, paying for new technology, implementing special programs—that small, independently owned newspapers, like where I work, have neither funds nor staff resources to implement.” Community and ethnic media outlets and communities of color have been in many cases disproportionately affected by this combined crisis of the decimation of local news sources, the economic impact of the pandemic, and the distortions of disinformation campaigns.

- Undermined trust in the press. The spread of disinformation has tainted public perception even of news organizations that have established ethics codes and undertake to demonstrate that they merit public trust. Political partisans from President Donald J. Trump on down have used accusations of “fake news” in an explicit attempt to undermine reporting they do not like. Disinformation and false accusations about the veracity of facts can leave individuals confused and communities divided, unsure what sources to rely upon, potentially leading them to put news outlets with ethics and standards codes into the same bucket as purveyors of falsehoods. This has led to growing distrust: according to a 2021 report by the Pew Research Center, only 58 percent of Americans say they have at least some trust in the information that comes from national news organizations, down from 65 percent in 2019, and only 12 percent say they have “a lot” of trust. Although their number is dwindling, local news organizations still are perceived more favorably: 75 percent still say they have at least some trust in local outlets compared with 79 percent in 2019. However, the partisan gap in trust in news media is dramatic; the percentage of those who identify as Republican with at least some trust in national news organizations dropped from 70 percent in 2016 to 35 percent in 2021, according to the Pew research. This has important implications for the ability of news organizations that value factual reporting to have an impact with their audiences as they attempt to counter false information. Said one respondent to the PEN America survey, “As a public affairs editor, the spread of misinformation about the 2020 election in particular is a major and ongoing concern. Not just because the claim that the election was stolen is false, but because people who believe it was stolen will not trust any other reporting we do on politics and public figures because they do not believe us on that fundamental point. It exacerbates and hastens the separate realities news consumers are living in.”

“Accurate information is the currency of newspapers,’’ said one respondent. “Disinformation should be regarded as our biggest threat.

Countering Disinformation is Urgent and Challenging for News Outlets

Virtually all the reporters and editors who responded to PEN America’s survey consider disinformation to be a serious problem for journalism today: 81 percent say it is a very serious problem, and 16 percent say somewhat serious. A substantial majority also characterize detecting and addressing disinformation as a priority at their news outlet, with 40 percent saying it is treated as “urgent” and 47 percent saying it is considered “important but not urgent.” Asked which of three consequences of disinformation worried them most, 62 percent said the spreading of inaccurate information that could cause harm, 35 percent said the undermining of the public’s confidence in news coverage, and 3 percent said distracting people’s attention from important news. Most reporters and editors expressed confidence in their own ability to detect disinformation they may come across in their work, with 60 percent saying they had “a lot” of confidence and 39 percent “some.” However, in response to a separate question about the impact of disinformation on journalists, 11 percent said, “I have unknowingly reported disinformation myself.” “Accurate information is the currency of newspapers,” said one respondent. “Disinformation should be regarded as our biggest threat.”

Asked what approach news outlets should take to disinformation, 54 percent of the editors and reporters responding thought every effort should be made to debunk false or misleading content despite the risk of thereby amplifying the falsehood. By contrast, 27 percent thought “news outlets should be extremely discerning about when to debunk disinformation—even if it means falsehoods go unaddressed—because writing about it only gives it more visibility.” A sizable number, 19 percent, were unsure which approach was better. “Realizing that there are actually risks here—exposing people to disinformation, and making the problem in some ways worse—that’s got a level of nuance to it for newsrooms, which already don’t have a lot of resources, which are already trying to make judgment calls on any given day, or in any given hour,” said Craig Silverman, a veteran disinformation reporter at ProPublica. In a 2020 case illustrative of this issue, The New York Times investigated how a doctored video of Joe Biden appearing to make racist comments had spread broadly enough to rack up nearly 2 million views and found that the video had gotten a crucial boost from being embedded by mainstream news outlets setting out to debunk it. “We definitely need to have this discussion, and establish professional and acceptable guidelines” on how news outlets should handle reporting on disinformation, a survey respondent wrote. “To debunk or not debunk—that is the question.”

Disinformation Has Significant Professional and Personal Impact on Journalists

The survey results show that dealing with disinformation is a consuming challenge for reporters and editors, one that imposes new professional burdens, demands more skills, processes, and time, and takes a personal toll. Only 21 percent of those responding said they hardly ever or never confront what they would classify as disinformation—as distinct from other reporting challenges—in their work. By contrast, 76 percent said they have to deal with disinformation regularly—writing about it, debunking it, explaining it, or uncovering it—with 61 percent saying this need arises some days and 15 percent saying it occurred every or most days. “The attacks feel overwhelming—from authoritarian governments, from nonstate actors with political agendas, and now from some U.S. officials themselves,” one respondent said. “It is exhausting to be a journalist right now—the combination of economic precariousness with all the mistrust and noise out there.”

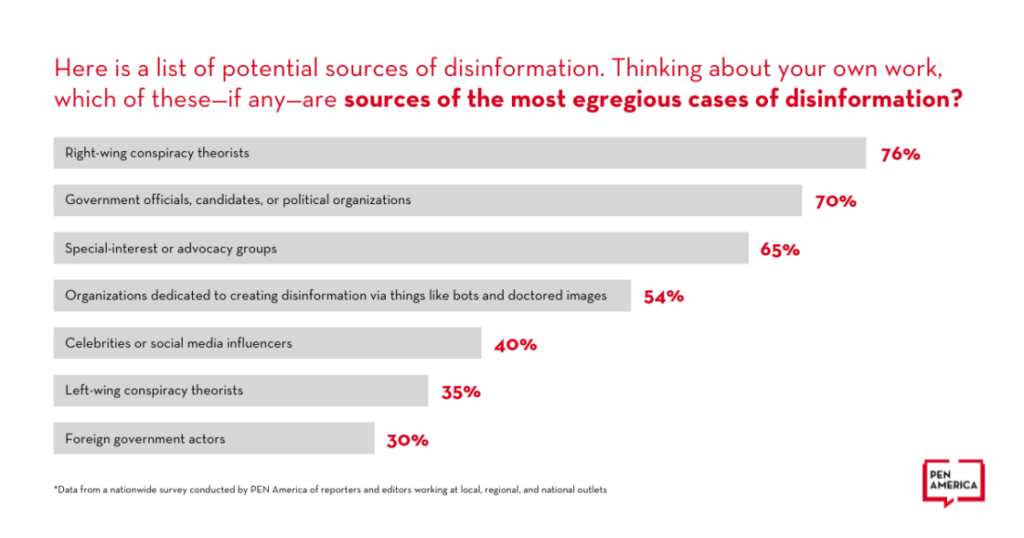

The journalists responding identified the sources of the most egregious cases of disinformation they encounter in their work as first, right-wing conspiracy theorists and secondly, government officials, candidates, or political organizations. They said they encountered disinformation from a range of other sources relatively frequently, too.

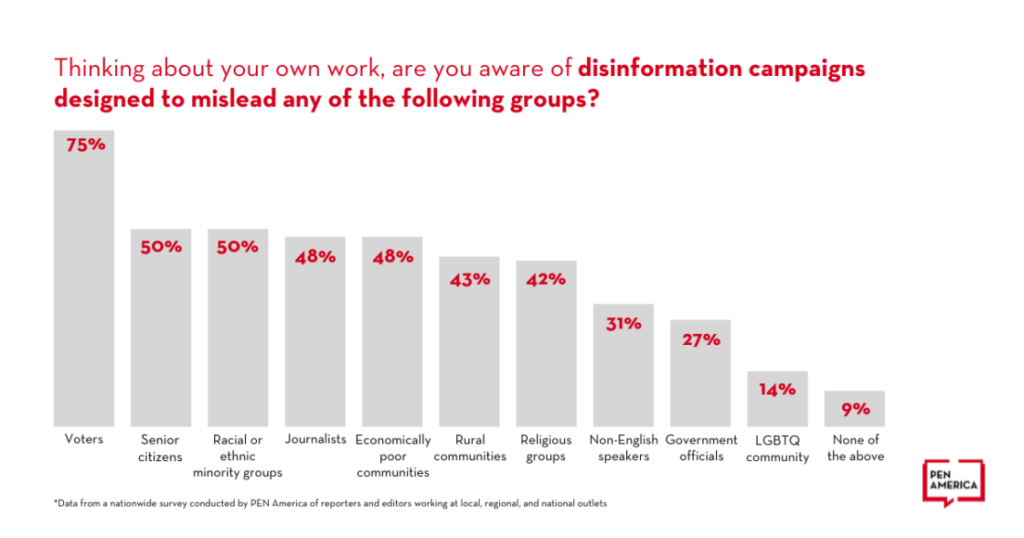

Asked about who, in their experience, disinformation purveyors were likely to target, the journalists ranked voters the most frequent but not the only likely target they have seen. When respondents were disaggregated by race, journalists who are people of color are notably more likely to be aware of disinformation campaigns designed to mislead racial or ethnic minority groups (72 percent versus the 46 percent of journalists who are white who said they are aware of this targeting), poorer communities, and non-English speakers. Latina journalist Maritza L. Félix, founder of Conecta Arizona, a “news-you-can-use service in Spanish” noted, “We have poor access to good information in our language in the U.S., which is why our communities are subjects of misinformation … We are the target, and culture always plays a role. For example, with the pandemic and the home remedies that don’t always align with science.”

Working in an environment so awash in disinformation has major implications for the journalists surveyed. Sixty-five percent said they have faced hostility from the public and 53 percent said they had found it necessary to be vigilant about limiting their personal data on the internet. Many reflected on the implications of their experience for their profession: 42 percent said they felt some portion of their audience had lost trust in them, 30 percent agreed “it’s harder to do my work because sources are less likely to respond to my requests,” and 27 percent said it takes them far longer to finish a story.

WE NEED MORE JOURNALISTS! THE ONES WHO ARE LEFT ARE OVERWHELMED AND DO NOT HAVE THE TIME TO TAKE ON THE ENTIRE WORLD OF DISINFORMATION! (sorry for yelling).

A survey respondent

Journalists facing the challenges of countering disinformation reflected on doing so when already stretched by the diminished resources of an economically imperiled news industry and operating amid the wave of hostility fueled by right-wing politicians and extremists. Nearly half (48 percent) said they feel frustrated or overwhelmed and 27 percent said they had seriously considered leaving the profession. “It’s kind of like playing whack-a-mole,” said Jareen Imam, a former NBC News manager who focused on story verification. “They just can’t spend that much time debunking or correcting misinformation because it’s so pervasive.” One survey respondent wrote, “The need to counter disinformation runs up against the need to report all the actual things happening out there. And so on many days, it just can’t be the priority, given all the other things our reporters have to cover.” Added another, “WE NEED MORE JOURNALISTS! THE ONES WHO ARE LEFT ARE OVERWHELMED AND DO NOT HAVE THE TIME TO TAKE ON THE ENTIRE WORLD OF DISINFORMATION! (sorry for yelling).”

The disinformation epidemic is inseparable from the rise in threats, harassment, and intimidation targeting journalists. Reporters who focus on debunking falsehoods or investigating disinformation campaigns are frequently targets of efforts to intimidate them into silence or self-censorship. Disinformation is also deployed against individual journalists and media outlets to undermine their credibility and integrity. Fifty-eight percent of the survey respondents said they had been subjected to one or more tactics of intimidation, including 41 percent who said they had received threatening phone calls, emails, or letters, and 22 percent who had been harassed in person while doing their job. Fifteen percent said they had added personal security precautions to their daily routine due to fears for their safety. Anita Chabria of the Los Angeles Times recounted how after she and a colleague reported in 2021 on a far-right militia-backed group with disinformation-based rhetoric that was working to take over local governments in Northern California, a leader of the group went on a podcast to call her and her reporting partner Nazis who needed to be “taken care of.” “That’s a threat that’s meant to intimidate,” said Chabria. “That’s meant to make me think twice before I follow up on that story, right? That’s the kind of thing—that’s so common.” Chabria said she now keeps a bullet-proof vest in her closet.

Even when not actualized, these threats create stress that significantly hampers journalists’ ability to work, a phenomenon that news outlets are increasingly being called upon to understand and address. “We need to take seriously the impact of our work on the mental health of ourselves and our colleagues,” said one respondent. “We need to think about . . . how we can put in place systemic protections for our people. That’s something that I think we’re not doing enough of.” Chabria agreed newsrooms have been looking at these cases as “one-offs. Like, ‘Oh, this reporter is working on this story and these people are coming after them.’ But it’s a tactic of the extremists. And (newsrooms) are not protecting our journalists from that tactic in a blanket, thoughtful kind of way that acknowledges it is widespread.”

Harassment using digital platforms, from violent threats and hateful slurs to sexual harassment and doxing, is a damaging component of this perilous environment for journalists, including those working to debunk disinformation. Of the survey respondents, 21 percent said they had been trolled or doxed online, and 7 percent said they had been subjected to “catfishing,” whereby a real person uses a fake identity online. O’Brien, while on the disinformation beat for HuffPost, said that after he reached out for comment to the operator of an influential Twitter account that regularly spread Islamophobic lies, the person tweeted a barrage of false attacks against him to her 200,000-plus followers. An “avalanche of abuse and death threats” resulted, some even before the story was published, he said. Another journalist responding to the survey recounted how she was attacked within her own community: “When I said I was trolled it was actually more that I was cyberstalked. There was a Facebook group dedicated to cyberstalking me which, unknown to the creators, was public, so I could see everything they were saying. I mentioned to someone in town that I knew of its existence and the group was taken private within an hour.”

Almost all the journalists said the prevalence of disinformation had caused changes in how they practice journalism and experience their profession.

Two-thirds of those responding said they more frequently directly debunk falsehoods or expand the context they provide in their stories. “Journalists can model responsible digital citizenship and within their work be more transparent about where information came from, how it was acquired, etc., so readers can more easily retrace steps,” wrote one respondent. Félix, whose outlet serves Spanish-language communities along the U.S.-Mexico border, uncovered immigration lawyers peddling their services based on false claims about impending border closings or visa risks from getting U.S. vaccinations. “They were just taking advantage of people,” she said. Conecta Arizona compiled these misinformation-laden videos from Facebook and TikTok and identified the falsehoods for the community. “I was trying to pull everything together for them to understand and actually told them that this attorney does not mean well, they are switching the information around for their benefit and interest.”

Journalists also said they had increased efforts at building or rebuilding trust with their audiences through transparency and outreach. “Disinformation and distrust of journalists has created a war with many fronts,” one said. “We need to enter the fray, to explain who we are, what we do and how we do it, and that we are a passionate and curious bunch of people committed to the truth.”

A third of those surveyed said they found themselves questioning their own journalistic instincts, a quarter cited the overwhelming amount of fact-checking required to counter purposeful efforts to deceive them, and 17 percent said they had decided to avoid reporting a story altogether for fear of accusations that their work was “fake news.”

News Outlets Need More and Better Approaches to Handling Disinformation

The survey findings indicated a lack of formalized responses by news outlets commensurate with the urgency, prevalence, and impact of disinformation on journalists. This was attributed to multiple interrelated factors including the complexity of the problem and the varied possible strategies for countering it, limited organizational resources and newsroom bandwidth, lack of expertise in tools and techniques, and multiple competing priorities.

Forty percent of the reporters and editors said their news outlet had no organizational approach to how it addressed the implications of disinformation for their journalism, and journalists were left on their own to deal with it. Another 21 percent said there were processes in place but they “still need a lot of work.” Only 30 percent thought their outlet had a generally effective approach. There was some difference in this assessment depending on where the respondent sat in a newsroom, with editors marginally more likely than reporters to think their outlet is responding effectively to disinformation. Thirty-four percent of those who identified as editors said their outlet had “put processes in place to counter disinformation that are generally effective,” compared to 25 percent of staff reporters who said this. Editors were also more likely than reporters—48 percent compared with 31 percent—to think their outlet is increasing emphasis on “choosing headlines, ledes, and photos that minimize their potential misuse as disinformation.”

Especially dramatic is the finding that of eight steps the survey offered as practices available to news organizations to counter disinformation and its impact, 32 percent said that their outlet has not taken a single one of them. Also of note are the gaps between those who see these approaches in place in their newsrooms and those who think they would likely be effective as journalistic practice in the context of disinformation.

There’s something significant that’s about to happen and newsrooms are not being proactive in figuring that out

A survey respondent

Especially dramatic is the finding that of eight steps the survey offered as practices available to news organizations to counter disinformation and its impact, 32 percent said that their outlet has not taken a single one of them. Also of note are the gaps between those who see these approaches in place in their newsrooms and those who think they would likely be effective as journalistic practice in the context of disinformation.

The situation is all the more uncertain at the majority of news organizations that are smaller and less resourced, especially where budget cuts and layoffs induced by the collapse of the news industry have thinned staff at all levels. “You have suggested a variety of improvements without considering that most local news organizations are so chronically reduced that we can scarcely cover a selectman’s meeting or a car crash,” one respondent said. “All would be marvelous and none would be possible. Attract people of different colors, ethnicities, backgrounds, etc.? Great idea but you can’t when they’d make more working at Target.”

Weak newsroom systems for quickly countering disinformation. Only 36 percent of respondents rated their news organization as “doing a good job” at having senior editors establish strong processes for countering disinformation. Even fewer, 23 percent, saw systems in place in their newsrooms to respond quickly to disinformation, although 73 percent thought this would be a generally effective action to take. Respondents noted that newsrooms face complex decisions editorially and in terms of resource priorities. They have to consider whether to cover and if so, how to cover, news events—rallies against COVID mask mandates for example—when the coverage could amplify disinformation. And bulking up rapid-response fact-checking teams could come at the expense of other priorities. Shana Black, who runs Black Girl Media, an independent media company with a largely African-American and female audience in northeast Ohio, framed the question as, “Should we spend money on the things we need to make sure that we combat misinformation, or should we make sure that people can get information on housing or economic recovery?”

The most frequently noted step newsrooms are taking, albeit reported by only 36 percent of the respondents, is placing more emphasis on choosing headlines, first paragraphs, and photos in order to minimize their potential misuse as disinformation. Shared as an example of the risk was a story in the Chicago Tribune with the headline “A ‘healthy’ doctor died two weeks after getting a COVID-19 vaccine; CDC is investigating why” that became the most viewed link on U.S. Facebook accounts in the first quarter of 2021, seen by nearly 54 million people. The New York Times later found that six of the top 20 sharers came from accounts that regularly post anti-vaccination content. Far fewer people saw the follow-up news that, after an autopsy, the doctor’s death was attributed to natural causes. “There should be a list of words to watch out for when crafting headlines and writing stories,” one survey participant said. “I spend a lot of time carefully thinking about the words I use, especially in headlines since that’s where most people stop reading.”

Respondents also noted that newsroom policies need to support directly calling out falsehoods. “We need ownership and management to support us in calling a lie a lie,” one wrote. “Too many times, everybody is stuck in the ‘both sides of the story’ concept of ‘balancing’ a report and it can create an impression that disinformation has a legit standing in some sort of ‘fair reporting’ context.” Added another, “When it can be proved that an individual has made a statement they know to be factually false, that must be named simply and directly . . . This must be done whenever one side has facts and data and the other side has nothing but rhetoric.”

Journalists reported being no match for the speed at which disinformation travels. “It’s so fast-paced that we can get it wrong, because you may not have time to vet and it can take off so quickly,” said Black. “You take one tweet or one piece on social media that’s disinformation tweeted or posted by an influencer or rapper. And now you’ve got a million people sharing it. And you’re going into the 6:00 news cycle, and so the question now becomes, is this a legit story? And you may not have time to vet it, but people are looking to you.” Added another respondent, “I would like us to put more resources into identifying false information as soon as it starts to spread and writing SEO [Search Engine Optimization] friendly stories that provide the countering facts. People who encounter misinformation are likely to Google to see if they can find something debunking it, and if there isn’t a headline doing that, the risk is they start believing the false source.”

Q 16. Thinking about the issues you cover, on which of these social networks – if any – do you see the greatest proliferation of disinformation? (Does not total to 100% due to multiple responses.)

88% Facebook; 63% Twitter; 45% YouTube; 24% Parler; 20% Instagram; 19% TikTok; 18% Nextdoor; 18% Reddit; 10% WhatsApp; 4% None of the above

The interplay of journalism and the social media platforms that disseminate both trustworthy and false reports is another newsroom challenge raised by respondents. “In addition to our journalism, the spread of our stories, mainly via social media or Google AMP, is always top of mind,” one said. “Many of the systems we rely on for our clicks (and as a result our advertising revenue), are the same systems that make widespread disinformation campaigns possible. It’s really depressing. There’s a thin line between clickbait and disinfo . . . I try to do my part, but it feels like I’m King Cnut trying to stop the breaking waves. That, on top of the tight deadlines and the never-ending demand for more from my editors, makes me feel like the waves are drowning me.” For some, pressure to be first in the digital space clashes with contesting disinformation. “Speed-to-market considerations and clickbait headlines vie for preeminence in editors’ thinking over taking time to make sure something is correct and complete including context,” a respondent said. “Until that competition lessens, we can be vulnerable to malign actors trying to con us.” Several blamed new news industry business models that have seen independent newspapers and broadcasters bought out and consolidated by hedge fund-driven corporations. “Local news outlets are being run over by a bus driven by corporate media. . . . My company—like other corporate media outlets—has centered its efforts on views and clicks,’’ said one respondent. “National headlines syndicated to our website and social media feeds have been sensationalized. If anything, they do nothing but promote the spread of disinformation.”

Few specialized fact-checking teams and limited disinformation beat reporting. While journalists noted the criticality of fact-checking and rigorous verification practices, only 14 percent reported that their newsrooms had established a dedicated in-house fact-checking team to monitor, debunk, and write stories about falsehoods put forth by disinformation purveyors. Half the respondents thought this would be generally effective. Several responses noted that few news organizations have the resources to build a comprehensive, expert staff solely to address falsehoods being spread across different content forms and platforms, including video, photography, social media, and text. Several said that they relied on larger news services with these departments for this content. One suggested, “The ability to provide explainer articles on controversial topics should be a model that more outlets use to fact-check widespread disinformation. These types of articles would boil down the issue with credited sources to inform the public.”

Others suggested debunking and reporting on disinformation should be integrated with regular “beat” reporting. “The problem with assigning ‘disinformation’ as a topic to a reporter/team is that no one person can possibly have enough expertise to easily know a) what’s not true and b) what’s most damaging,” said one. “If the outlet decides that the best counter-disinformation strategy is to write a piece about how the information is not true, that has to be the job of the beat reporter with the expertise in that subject (which I don’t love, as a beat reporter who hates writing fact-checks, but it’s true).”

Some reporters and editors despaired about failing to reach those unmoored from a shared fact base. One respondent mentioned that their organization had partnered with a nonprofit fact-checking service thinking that a third party would convey legitimacy to their audience. Instead, the outlet found that people already distrustful only added the very reputable service to their list of groups to distrust. Said another, “The audience that would most need to hear a fact-check story *about* disinformation is already almost entirely gone from us. It is not worthwhile to write a story fact-checking an ‘alternative fact’ when the alternative fact exists in a separate and highly manufactured political reality.” A respondent who identified as a former fact-check reporter said that in their experience, “readers want to know facts and the truth, but they feel lectured to with ‘disinformation’ reporting and fact-check articles, building resentment and distrust of a media establishment that seems to have a mysterious authority and often misses critical context when producing mass amounts of content … Separately, ‘disinformation’ reporting is regularly politically weaponized, causing a whole set of other problems.”

Only 9 percent of the survey respondents said their news outlets had a journalist whose focus is disinformation and its impact. Silverman, who reports on disinformation for ProPublica, considers his beat as an important element of newsroom defense. “There is a cat and mouse game, where the techniques of the dis-informers, the approaches that they use, are constantly evolving,” he said. “And if you don’t have people whose full-time job, or part of their job, is to really stay on top of that then you’re going to miss stuff. Or in the worst-case scenario, you’re going to fall for something and give it your seal of approval and share something that’s false or misleading—which is one of the nightmare scenarios for journalists and news organizations.” Damaso Reyes,4Damaso Reyes consults for PEN America’s projects on community responses to disinformation. a journalist and media literacy expert, added, “I don’t think we fully understand the scope and scale and depth of misinformation. We’ve certainly begun to cover it more, and we will talk about it when it comes to QAnon or January 6 or COVID denial. But it’s become such an integrated part of many Americans’ lives, and we need to approach it holistically.”

The journalists surveyed were not fully convinced on the merits of establishing a disinformation beat, with 41 percent endorsing this approach as a response as generally effective. “I don’t know that it will do much to counter any of the harm on an individual level, but it is one of the most important issues facing our country, and it should be documented,” said one, adding, however, “My general feeling is that propaganda is very effective, and that most people who believe it are almost impossible to convince otherwise. Generally speaking, I think most individuals are a lost cause. Still, the impact is tremendous and should be reported on. Maybe this could spur large action to curb the flow of disinformation, which could keep more people from being duped.”

Too little media literacy. Journalists responding to the survey put high value on connecting with the communities they serve and helping them to understand both how trust-meriting news outlets function and how to identify disinformation. However, only 14 percent said their news outlets were putting partnerships in place to improve the public’s “media literacy.”5PEN America’s Knowing the News Media Literacy and Disinformation Defense toolkit can be found here. “Generally, I’ve found that people just don’t know enough about how we work,” one respondent said. “Once I explain to people the rigor and strength (and duration) of what actually happens when you report a story, how it gets edited and the checks it goes through, they are usually surprised and see it differently.” Said another, “Most non-media people I speak to are genuinely surprised when I explain that the opinion section is separate, figuratively and literally, from the wider newsroom.” A third respondent suggested that journalists should be “seen by the public as fixtures in their communities . . . I would be less likely to get harassed by people who regularly see me as part of their community and understand what I do.”

Several respondents urged reporters and editors to engage with the public outside the bounds of the specific stories they are working on. “It seems a shame that we need to ‘rebuild trust’ with communities we have served for decades, but that is the case,” one said. “Journalists by nature tend to shy away from public interaction, sometimes claiming it is the only way they can remain objective. We need to disabuse news organizations and newsrooms of that concept. Keeping ‘remote’ doesn’t equate to being ‘objective.’” Another acknowledged, however, that finding time for this added interaction is difficult: “We are so short-handed that we always are scurrying to get the core job done, which means we put too little emphasis on community.”

Notable weight was given to formal training for the public: “I do think media literacy and media education is key. So many readers can’t tell the difference between a legitimate news story and a fake news blog. And when they can, some trust the fake news outlet more than a legacy newspaper because the newspaper is viewed as ‘mainstream.’” Added another, “It’s not enough to train ourselves as journalists and newsroom staffs. We need to deliberately train our communities on how to discern, fact-check, and debunk disinformation in schools and daily conversation (without shouting). Making civics education, with media literacy as a component, should be required and mandatory education for the benefit and betterment of all.”

Q5. Does your news outlet mostly serve a general audience or does it mostly cater to a specific demographic community?

83% General audience; 17% Specific demographic community

Not enough attention to disinformation-targeted communities. Thirty-five percent of the survey respondents said that their news outlets had taken steps to attract and hire journalists to ensure the wide variety of perspectives in the newsroom necessary to better detect and dissect disinformation, a step 69 percent of those responding agreed would be generally effective in countering its impact. Only 21 percent said their news outlet is devoting resources to building relationships in communities where disinformation is more likely to circulate due to targeted disinformation campaigns. “Getting journalists out of their cultural/economic bubbles is key to understanding why disinformation can spread and how to cover stories that impact those communities so they can feel seen and understood,” one respondent noted. Added Félix, “We need to start changing … who we put in positions of leadership, and who’s representing the communities that we’re serving in our own newsroom …There’s so many things that we’re doing wrong that we can fix so easily to start combating misinformation before it actually starts.”

Research indicates that disinformation purveyors target communities underserved or ineffectively served by news sources,6Research shows the outsize impact of targeted disinformation on people of color, women, LGBTQIA+ communities, and the underserved by mainstream information sources. Discussion of this issue can be found here, here, and here. including those of color, where English is not the primary language, and where trustworthy news sources are scarce. “As smart people who create disinformation do, they are playing on existing divisions, an existing traumatic history, to make their case,” said Reyes. While overall there were relatively few differences in the survey responses from editors and journalists when disaggregated by race, the results did show that journalists of color are more likely to know about disinformation campaigns designed to mislead racial or ethnic minority groups. Seventy-two percent of journalists of color say they are aware of disinformation campaigns that target racial or ethnic minorities, compared to 46 percent of journalists who are white who say this. Journalists of color are also more likely than white journalists to be aware of disinformation campaigns targeting poor communities (63 percent versus 46 percent) and non-English speakers (48 percent versus 28 percent).

The issue of newsroom preparedness appears particularly urgent in newsrooms that are led by, cover, and/or serve minority communities. Several of the survey findings suggest that journalists of color are more likely to perceive a need for resources that could help them counter disinformation: seventy-four percent of white journalists, and the same share of journalists of color, say that “having systems in place to respond quickly to disinformation” would be a generally effective way of countering disinformation. But when that result is disaggregated by race, 15 percent of journalists of color say that their news outlets have such systems in place, compared to 24 percent of white journalists. Describing Spanish-language disinformation as “an avalanche coming after you,” Félix said the pandemic brought into relief the gaps in news available for English and for Spanish speakers, even from trustworthy sources. “You couldn’t find reliable information in Spanish–it was all bad Google translate,’’ she said, but her outlet was hard pressed to meet the need. “We just don’t have the resources. We always have this tiny slice of pie.” Additionally, 44 percent of journalists of color, compared to 62 percent of white journalists, say they have a lot of confidence in their own ability to detect disinformation.

PEN America’s extensive work directly with communities of color to combat disinformation about the COVID-19 vaccine showed a dearth of in-language, culturally competent messaging in the mainstream media, a byproduct of the “news deserts” phenomenon where the constriction of local news industry has left communities without reporters to cover them, shortfalls in diversity at existing news outlets, and other factors. This information vacuum, made more severe by pre-existing inequities, opens the door for peddlers of disinformation. “Dealing with misinformation is actually kind of a specialty,” said Reyes, who has worked closely with news organizations that serve communities of color. “So, are you getting that training? Are you getting resources? Do you know how to do a proper fact-check? Do you know how to counter misinformation without amplifying it? . . . In a lot of these newsrooms, you may be one of four or five journalists in the entire newsroom. So, do you have the time? Do you get the professional development to actually deal with the issue? The answer, for I would guess the vast majority of newsrooms that serve communities of color, is no.”

Journalists also pointed to the necessity of trusted messengers and specialized strategies tailored to different audiences. “The question becomes, how do you as a journalist balance wanting to make sure you’re promoting accurate information with perhaps a desire to accurately reflect what members of the community feel—even if what they feel is based on misinformation?” Reyes said. Black, whose media company serves a largely African-American audience, said she became interested in taking on the challenge of disinformation “because I realized a lot of my loved ones and family and friends and readers are the target.” Rather than focusing on debunking individual stories, she said, she tries to give her audience the tools to identify disinformation themselves to use in their communities. “It’s easier for them to be like, ‘no sister,’ or ‘no, auntie,’ or ‘no brother, that’s not real,’” she said.

Reporters and Editors and their News Outlets Need Strategies, Tools, and Training

Responses to PEN America’s survey show the gulf between the alarm about disinformation among journalists and the degree to which newsrooms are equipped with the strategies and tools they need to take action. News outlets perceive the immediacy of the disinformation threat, and reporters and editors feel its impact strongly, but they are challenged to put in place a comprehensive, systematic response. The reasons are for a large part understandable: lack of financial and professional resources, conflicting urgent priorities, shortfalls in specialized skills, and a shifting, surreptitious target in the falsehoods and their purveyors. Making it even harder are the discord and polarization in the communities that news outlets endeavor to serve and the historic failure of many to wholly engage the full breadth and diversity of their potential audiences. Also complicating the response are the factors that may make readers and listeners more susceptible to accepting falsehoods as facts, including lack of understanding about how trust-meriting news outlets function and the complexity of picking through floods of competing media.

At best about one in three of the journalists responding rated their news outlet as “doing a good job” when it came to a range of specific steps that could be taken to counter the impact of disinformation on the gathering and sharing of news. The most, 36 percent of respondents, thought their outlet was succeeding at having newsroom leaders put strong systems in place for countering disinformation; however, 33 percent saw need for improvement, 18 percent said their outlet falls far short on this, and 13 percent were not sure. (When the findings are disaggregated by newsroom title, editors were more confident, with 44 percent saying this was being handled well compared with 31 percent of staff reporters.) Only a third thought their newsroom was doing well at knowing when to “prebunk,” preemptively reporting accurate information before disinformation spreads, and even fewer—21 percent—saw effective efforts to address how disinformation travels through communities that are particularly vulnerable to disinformation campaigns, due to language, isolation, and other factors.

Large majorities of the journalists indicated that they needed to learn more about tools that could help them counter disinformation in their own work. Respondents commented that these methodologies are not generally taught in journalism schools and, given the lack of systematic newsroom protocols for dealing with disinformation, few news outlets provide regular training in these skills. A mere 18 percent of respondents rated their news organization as doing a good job when it comes to offering professional development on how to detect and report on disinformation. Only 21 percent said they were being provided with training and guidelines for journalists on how to report on disinformation, an intervention that 80 percent said they thought would be generally effective. “Everyone in the newsroom should be trained in basic news-gathering from social media—for instance, being able to see a photo or video and be discerning about it and be able to take basic steps to check that it’s legitimate,” said Imam, the former NBC News manager who focused on story verification. “This shouldn’t be something for only a small specialist team to do, as it often is.”

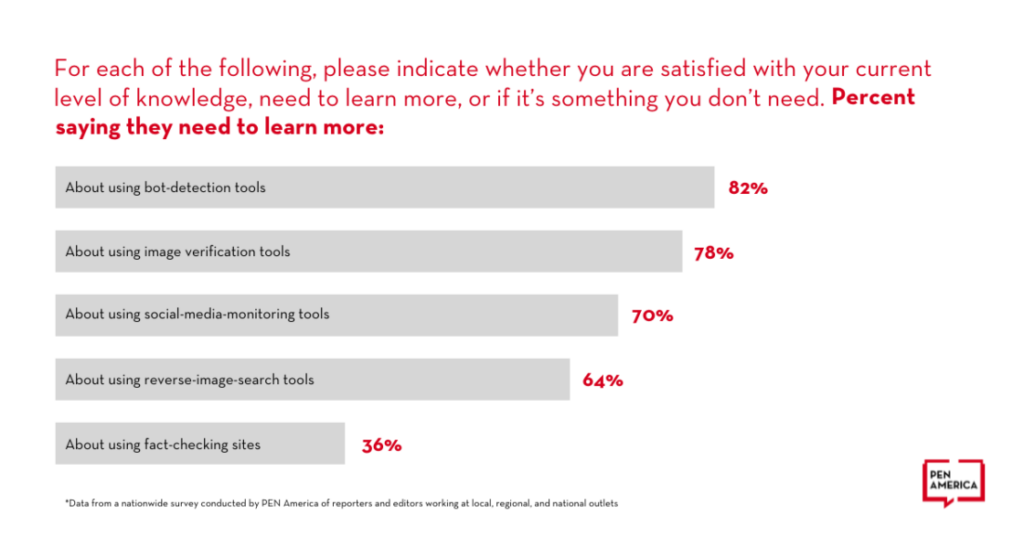

Only 19 percent of those surveyed said they are using new technologies and tools to detect disinformation. Asked about a series of tools for detecting efforts at injecting disinformation into news coverage, the majority of respondents said they need to learn more about most of them. The greatest gap was in knowledge of how to use bot-detection and image-verification tools. The most confidence was in the use of fact-checking sites.

It’s kind of strange to me that we don’t think more about ways to help newsrooms share resources … On misinformation, nobody should be competing.

Claire Wardle, Researcher

Specialists in the field explain that online tools for disinformation detection are generally not purpose-built for journalists, and as a result rarely intuitive to use. There is little incentive for technology companies to do better because journalists represent a much smaller market than information-security professionals. And even when these methodologies are more tailored for journalism, there’s currently no effective bridge to make reporters aware of them and get them into newsrooms. “There’s the tools—and then there’s making sure newsrooms know about them and are trained to use them, and that they’re consistently being updated with the latest stuff,” said Silverman, of ProPublica. “That’s a significant thing, which is really piecemeal right now.” He cited skills including using reverse-image search tools, evaluating social media accounts, and doing “whois” searches to find domain-name owners as “things that every single journalist on every single beat needs to know how to do.”

Other newsroom assets that journalists said should be developed include a database of experts, organized by topics, to whom reporters can turn for help in debunking disinformation, and mechanisms for collaborating across news outlets in one ownership group (one example noted is VERIFY, a central hub used for fact-checking by 49 newsrooms owned by TEGNA) or even among different otherwise competitive outlets. “We’ve always had pool systems, like covering the president, or in the U.K. the Royal Family,” said Claire Wardle, a disinformation researcher. “It’s kind of strange to me that we don’t think more about ways to help newsrooms share resources. . . . On misinformation, nobody should be competing.” Félix also surfaced the dearth of Spanish-language fact-checking initiatives at large outlets, and that “there’s nothing specifically in Spanish with a cultural lens to the information they’re verifying.”

A survey participant noted the potential of collaborations between local newsrooms “best positioned to develop relationships with the most susceptible audiences and provide them with quality information,” and national news organizations that would support them with resources and expertise and spotlight their work. Another respondent said connections between journalists and organizations studying and addressing disinformation are too weak. “They are seen as unrelated efforts (when) obviously, they are quite connected!” the journalist wrote. “I hope this study can lead to more resources and viewpoints on how journalists and those fighting disinformation can work together.”

Next Steps

Analysis of these survey results shows an urgent need to support newsrooms in developing comprehensive, systematic strategies that will further equip editors and reporters to meet the challenges of journalism practiced amid an information space polluted by disinformation. An effective response requires formulating best practices and protocols, providing access to tools and training, and countering the impact on journalists’ security and well-being. Outside the newsroom, renewed efforts are required to expand journalists’ engagement with audiences to build understanding of what makes a news source trustworthy and how to discern facts from falsehoods. This includes prioritized outreach to communities that are especially targeted by purveyors of disinformation and underserved by news outlets. To meet these needs made evident by the survey responses, PEN America has identified the following necessary steps:

- Convene news executives and journalists to further assess the survey findings and contextualize them in the experiences of a range of newsrooms, editors, and reporters, with the objective of formulating strategies and identifying resources to support them.

- Develop a comprehensive, scalable guide to disinformation resilience for journalists and newsrooms, including threat-modeling guidance, blueprints for protocols for handling disinformation, checklists of required tools and training plans, and guidance for community engagement on media literacy.

- Deliver in-newsroom support for developing policies and procedures and providing training on core tools and techniques, tailored for news outlets of varying sizes and resources.

- Inform newsroom anti-disinformation strategies with findings and strategies from ongoing community media literacy and online harassment defense initiatives.

Acknowledgements

This report was written by Dru Menaker, chief operating officer at PEN America, with substantial research, input, and organizational support from Hannah Waltz, coordinator, U.S. Free Expression Programs. Consultant Zachary Roth conducted interviews and provided editorial content. PEN America’s Senior Director for Free Expression Programs, Summer Lopez, reviewed the report. Graphics and layout were designed by Melissa Joskow. James Tager is director of research at PEN America.

Ann Duffett of FDR Group prepared and fielded the survey and provided analysis of the responses. Special thanks are extended to the reporters, editors, and experts on disinformation’s impact on the media who informed the preparation of the questions and reviewed and reflected on the findings. PEN America is deeply grateful to the more than 1,000 journalists who gave of their time, expertise, and experiences to respond to the survey—and who continue to stand for facts, accountability, and informed discourse.

Our appreciation goes to Craig Newmark Philanthropies for support of this project.