Break Out: An Interview with TheaterLab’s Lanie Zipoy

This interview is part of Works of Justice, an online series that features content connected to the PEN America Prison and Justice Writing Program. Works of Justice reflects on the relationship between writing and incarceration and presents challenging conversations about criminal justice in the United States.

Our work at PEN America’s Prison Writing Program has been profoundly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, as incarcerated people remain one of the most at-risk populations in the nation. Amidst this anxiety, uncertainty, and loss, we have sought to foreground the spirit and resilience of incarcerated writers—linking their literary dispatches to interviews with experts in criminal justice and opportunities for advocacy—through the launch of Temperature Check, our rapid-response content series focused on COVID-19 in prisons.

Our upcoming 2020 “Break Out” Prison Writing Awards event arrives at a harrowing time in our living history. On the evening of November 17, we’ll honor the PEN America Prison Writing Contest winners by staging works in the categories of fiction, nonfiction, drama, memoir, and poetry. Taking place virtually for the first time ever, our shared experience will be community-driven, interactive and—while centering the gravity of this pandemic era—celebratory.

This is also the first year that the annual “Break Out” celebration has been professionally curated! The excellent array of poets and actors who expertly bring the award-winning writing to life on screen is thanks to TheaterLab’s Lanie Zipoy, a Memphis-born, New York-based director and creative producer working in film and theater. Earlier this year, her feature film directorial debut, The Subject—starring Jason Biggs, Emmy Award nominee Aunjanue Ellis, and Anabelle Acosta—won multiple Best Narrative Feature Film awards at acclaimed film festivals.

I had the pleasure of speaking with Lanie about her curatorial process. We discussed the unique challenges and opportunities of crafting an entirely digital event, as well as the possibility for art to bridge the isolation that has shaped so much of this year both within and beyond the prison walls.

After reading, we hope you’ll consider joining us for “Break Out” on November 17 at 8pm ET. Admission is free with RSVP.

MERY CONCEPCIÓN: Typically, writers read their own work at literary events, an act that is often cherished as an opportunity to present their authorship and voice. Given that incarcerated writers are unable to present their own work due to technological, censorial, and physical barriers when planning the “Break Out” event, how did you think about new ways of bringing each writer’s authorial voice to the fore, despite their absence?

LANIE ZIPOY: Honoring the writer’s authorial voice is the most important element of the “Break Out” event.

My sister deserves a huge shoutout on this. She has taught middle schoolers, incarcerated teenagers, and college students while working toward her Ph.D. in creative nonfiction. She always stresses a close reading and critical analysis of the text to her students. Her teaching has infiltrated my curatorial process.

With that in mind, I read each piece a couple of times. I sat with them, chewed on them, and inspected them for clues to the identity of the writer. I mined them for what felt essential and powerful in each one. Then, I put them away for a week, letting them inhabit my subconscious and even my dreams. After those seven days, I reread these wonderful poems, essays, and works of drama again to figure out how they could sing and soar and receive the care that they deserved. Like a puzzle, I pieced together slowly who might align with each work. I started with the poets, and luckily, when I sent my dream list of poets for each piece, Caits [Meissner, Prison and Justice Writing Program Director] and Robbie [Pollock, Program Manager] already knew many of them. They connected me. That was such a dream.

These performers stood in for incarcerated writers because of their deep commitment to breaking down barriers and supporting these writer’s voices. Everyone I asked jumped on board immediately.

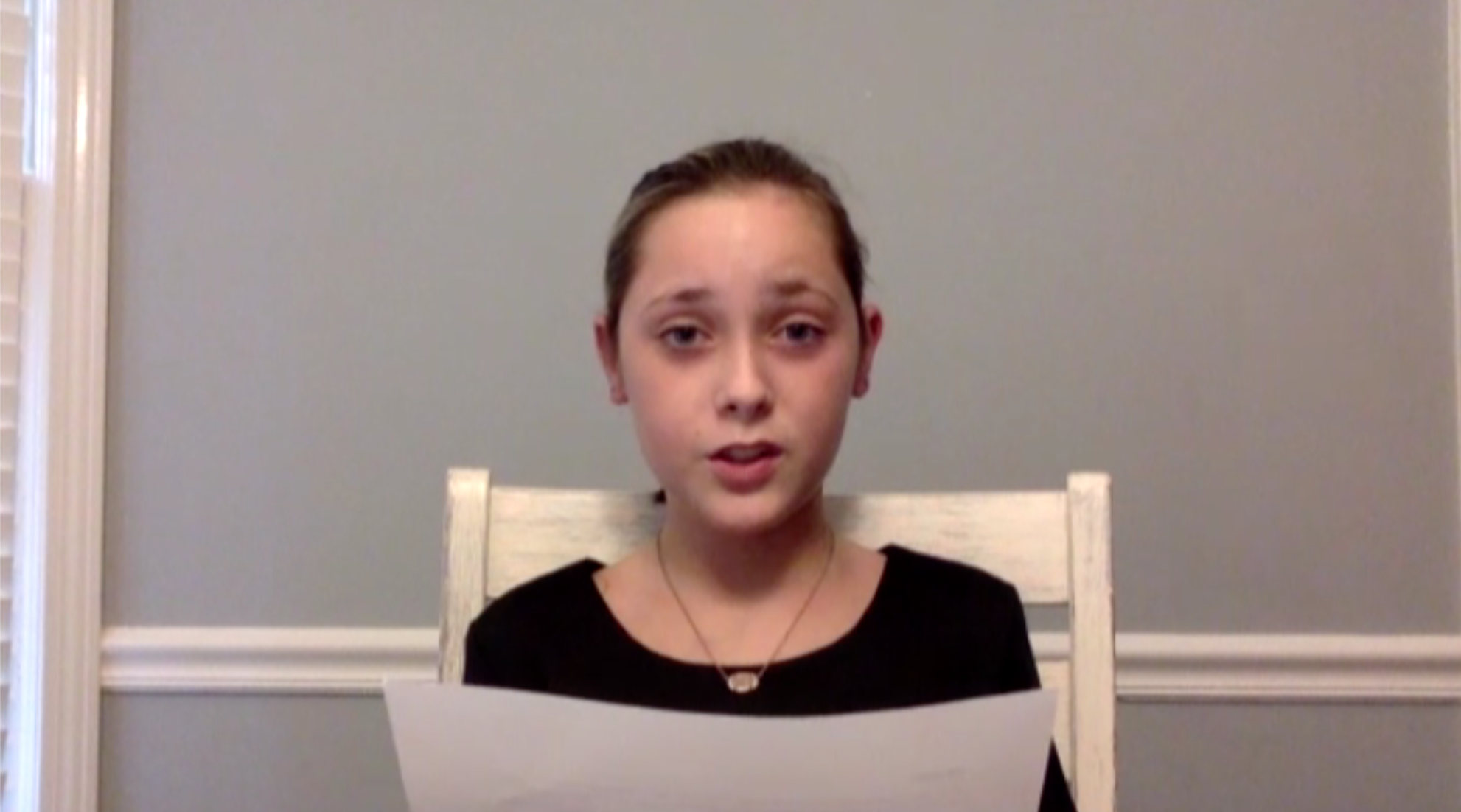

Writer Morgan Parker reading Demetrius A. Buckley’s poem “In Response to Loneliness,” which received an honorable mention in the 2020 PEN America Prison Writing Contest

CONCEPCIÓN: Following up on the previous question, I’m interested in hearing a bit about some of the curatorial choices you made when assigning each performer the work they would be reading. I was particularly drawn to Morgan Parker’s reading of “In Response to Loneliness” by Demetrius Buckley, a candid and gut-wrenching meditation on the effects of isolation. What informed your decision to have her read this piece?

ZIPOY: All of the poets in the “Break Out” event are cherished and phenomenal in their own rights. Poetry is the thing that got me through the early days of the pandemic. Three times a week, I attended intimate, virtual poetry readings; many of the poets who stand in for incarcerated writers in the “Break Out” event were featured in those impromptu poetry reading series.

Demetrius Buckley’s “In Response to Loneliness” punches you in the stomach and heart with its look at isolation. It knocks the breath out of you and leaves you aching, the way poetry often does. The same can be said of Morgan Parker’s work. It is stunning and vibrant on the page, and even more dynamic in Morgan’s reading of it. They seemed like an exquisite pairing, where Demetrius’s words and structure would easily land with Morgan. When Morgan sent in the reading of “In Response to Loneliness,” it was more outstanding than I imagined. And, secretly, I was beyond delighted because Morgan was one of the poets I hadn’t seen read live on those pandemic poetry readings. Here was the chance to experience Morgan’s work and honor Demetrius’s as well.

“Poetry is the thing that got me through the early days of the pandemic. Three times a week, I attended intimate, virtual poetry readings; many of the poets who stand in for incarcerated writers in the ‘Break Out’ event were featured in those impromptu poetry reading series.”

CONCEPCIÓN: The incarcerated writers we work with at PEN America’s Prison Writing Program face isolation on many fronts: They are physically removed from their loved ones on the outside, distanced from literary communities to share and support their work, and face the constant threat of being placed in solitary confinement for the act of self-expression. In the times of COVID-19, our program’s understanding of writing as a connective act is more important than ever. How did this ethic translate to your curation process, when working with performers who are not only isolated from the writer whose work they are reading, but from the immediate feedback of live audiences and energy of other performers as well?

ZIPOY: Everyone is struggling with some form of isolation right now. Of course, we’d prefer to share this experience—these readings—with a live audience. Ideally, the incarcerated writers could read their own work in front of this audience, and take in the wonderful feedback and applause they would surely receive.

The selected works by incarcerated writers are powerful, moving, meaningful, funny, enlightening, heartbreaking. The words on the page transport the performer to another place. Within that, there is community. There is strength. There is hope. There is conversation. It’s not the same as it was before COVID-19 hit, but this communion is important, even on these new terms. We see life and ourselves reflected in these words—words that connect us.

Every one of the performers felt a deep connection to the writing. That connection buoyed me in the curatorial process and supported the performers during their work on the pieces. Artists are resilient and find ways to make art no matter the limitations put upon them. This shared space, this shared journey felt like something to be embraced.

Additionally, some of the performers have missed working on new work, and this opportunity was a lifeline—a chance to be creative and to be of service.

“The selected works by incarcerated writers are powerful, moving, meaningful, funny, enlightening, heartbreaking. The words on the page transport the performer to another place. Within that, there is community. There is strength. There is hope. There is conversation. It’s not the same as it was before COVID-19 hit, but this communion is important, even on these new terms. We see life and ourselves reflected in these words—words that connect us.”

CONCEPCIÓN: Coming from TheaterLab, an organization whose central mission is to explore the “nature of live performance,” I can imagine that this year’s “Break Out” event was different from most of the performances you have worked on in the past—in ways touched on in the previous question and beyond. What were some challenges, but also some opportunities, that revealed themselves as you curated this pre-recorded digital event?

ZIPOY: “Break Out” is a paradigm shift for TheaterLab, where pre-pandemic we focused on live performance with audiences and artists generally in the same room, sharing space and time. Theater, though, has changed immensely since its inception generations ago, and it can hold multitudes. One of the things I most admire about theater-makers is their ability to adapt and problem solve. That was the case with “Break Out.”

The performers and I approached the work in much of the same way we do with stage work. We interrogated the text, talked through the beats, and the overall arc. But, we also had to consider the realities of the digital, recorded space that is not quite a movie yet different from stage work. We wanted each piece to have an intimacy between performer and camera, with that approach hopefully translating to the audience as well. There was something freeing about working in this way.

Another benefit of this digital work is that performers and poets, who are not based in New York City, were able to be part of this event. That widens the circle in such a beautiful way. It also provides a deeper richness to Break Out since PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing program serves incarcerated writers across the country.

CONCEPCIÓN: The piece Supernova by PEN America Prison Writing Award winner Elizabeth Hawes is the longest of the performances and features monologues performed by five different actors, including a child. Each monologue is about a particular woman’s experience in prison, exploring how incarceration affects their roles as mothers, partners, and daughters. Could you talk a bit about the process of selecting excerpts from Hawes’s screenplay and staging this play in a digital format?

ZIPOY: Elizabeth Hawes’s Supernova is a beautiful, heartbreaking, witty documentary-style play about incarcerated women from different backgrounds and identities. Many of the vignettes touch upon motherhood and what it is like to be a mother separated from her children.

I would absolutely love to direct it for the stage. It calls for all of the performers to be onstage for the performance’s duration—in the background and shadows—except during their scenes when they inhabit the front of the stage. That powerful choice underscores the isolation, loneliness, yet community these women find in prison.

All of the vignettes deserve to be performed in front of a live audience. This play will cause such a ripple, a wave of love, wistfulness in the audience members’ hearts.

I selected to present these certain vignettes for a couple of reasons. The first one is named “Mental Illness/Memphis: A-1 Sauce.” I’m from Memphis, and the writing literally hit home. The language was spot on. I cast Markia Pankey, who currently resides in the South. I knew she could bring the Memphis accent.

The child scene ends the play and offers such a heart-wrenching look at how incarceration affects children. It felt right to end this truncated reading with that vignette, to leave the audience thinking about incarceration’s harmful effects on families.

The other three vignettes offered a range of experiences from domestic violence to regret to outrage over the treatment of Native peoples and immigrants. Tanis Parenteau—who does a marvelous reading—and I spoke about how often Native peoples are not seen in entertainment, in general, and more specifically, on popular TV shows about incarcerated life. In those instances, Native peoples are rarely mentioned despite being incarcerated at a much higher rate than other populations. It was, therefore, important to include this piece in Supernova.

CONCEPCIÓN: One of my favorite pieces from the event is the satirical sketch piece “ConStar Ankle Bracelets,” which uses humor to reveal the electronic monitoring of people on parole and probation as a distinct kind of unfreedom. The actors, who recorded the segments as if actual commercials—in costume and in local environments outside the home—seemed to really connect with this work. In your opinion, why is this piece so successful and evocative?

ZIPOY: I agree wholeheartedly that this piece is amazing. The success lies with director Kristin McCarthy Parker, who is known for inventive staging and using found objects for props in her work with Recent Cutbacks—a troupe that parodies blockbuster films and other forms of large-scale entertainment.

I first reached out to her because I believed that she would bring a whimsical and playful take on “ConStar” that would center the humor. That was of the utmost importance. Satire and parody offer joy while also bringing truth to light. “ConStar” is really humorous, yet it acutely delves into how parole and probation create the feeling of unfreedom, as you call it.

There are seven vignettes in “ConStar,” but Kristin focused on the ones that would be easiest to film, given the current pandemic and social distancing guidelines. One location was switched from a living room to a park bench, but it kept the same hilarious core of the original work. The filmed piece is truly her brainchild and uses many elements that her stage work is known for, such as the creation of the ankle monitor.

Kristin cast “ConStar” with performers that we’ve both worked with, folks who are some of the most generous, delightful people and accomplished performers. They are known for their physical work in terms of movement, comedy, and even mime as well as voice acting for the two voices of “ConStar.” They brought the same dedication they do to their stagecraft, and in my opinion, they hit a home run. Glad you enjoyed it too.

RSVP for the “Break Out” awards celebration on November 17 at 8pm ET »