Works of Justice is an online series that features content connected to the PEN America Prison and Justice Writing Program, reflecting on the relationship between writing and incarceration, and presenting challenging conversations about criminal justice in the United States.

Here, at the PEN America Prison Writing Program, our team understands the barriers writers in prison face with getting their work published. Challenges range from lack of access to typewriters (nevermind computers), paper, writing tools, research materials, and the internet. Physical mail is censored and scrutinized in both directions. The repeated letters to publishers are costly for writers in prison, and often met with no response.

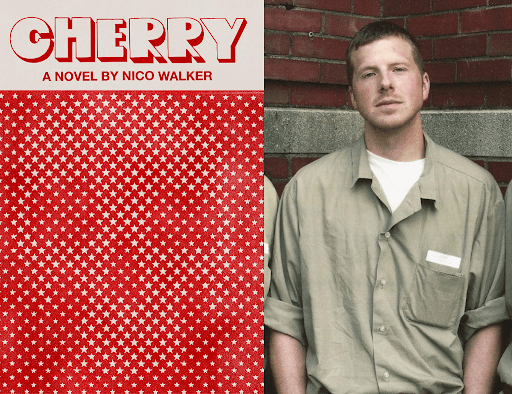

Despite these obstacles, books by incarcerated writers have been published by renowned publishing houses. Tim O’Connell, Senior Editor at Knopf, continues to look for fresh narratives in small and independent presses and from frequently overlooked writers. There is an element of risk in this, but O’Connell’s taken chances since beginning his career by signing a writer without an agent. As editor for Nico Walker’s debut novel, Cherry, O’Connell saw the adversity incarcerated writers face and the deep commitment and creativity it takes to publish from prison. His work with Walker paid off in a critically-acclaimed novel that provides a sharp-voiced and raw indictment of modern American life. The book was a finalist for the 2019 PEN/Hemingway Award for Best Debut Novel, and has been praised widely in high profile publications such as The Washington Post, The New York Times Book Review, The New Yorker, and Vulture.

On Knopf’s website, O’Connell describes his first encounter with Walker’s manuscript, in which the protagonist, a heroin-addicted Iraq veteran who, under the influence of drug use, begins robbing banks:

On Friday, April 21, 2017 at 7:00 a.m., I found myself standing outside a federal prison with Matthew Johnson of Fat Possum Records. Months earlier, as we met for lunch in a bar that didn’t serve food, Matthew had shown me pages from Nico Walker’s debut novel. They were typed pages, the only copy of the work. And they were brilliant. So much heat to them, I was surprised they hadn’t spontaneously combusted. It was the emotion in the sentences. The black tar humor. All the hopes and dreams of young love buried under the weight of war and bureaucracy, right there in a line or two.

Publishing Power—Liberating Great Work is the final event in the Works of Justice series in collaboration with Housing Works Bookstore and Café. For this occasion, we gathered a group of writers, editors, and publishers to confront the challenges and ethics of publishing incarcerated writers, and reimagine the boundaries of what is possible. In anticipation of this unprecedented panel, we had the pleasure of interviewing Tim O’Connell about his work with Nico Walker.

ROBLEDO: Tell us about the first time you brought this story to the editorial board meeting. What were some of your and your colleagues’ reservations about working with a long-term incarcerated writer?

O’CONNELL: As Anthony Bourdain would say, I had no reservations. Nico’s writing was some of the best and most vibrant, funny, and dark stuff I had seen in years. From the very beginning my goal was to go through this process like Nico was any other writer. I would meet him in person like my other writers. We would try to talk, edit, review covers like any other writer. That was the goal and of course the situation presented unique challenges, but when presenting to colleagues my message was: We have to publish Nico because he is an incredible writer.

ROBLEDO: What are the challenges of working with an author who has to reveal so much of themselves, and yet has a limited avenue of self-expression?

O’CONNELL: Any writer who puts themselves on the page makes themselves extremely vulnerable. And at the end of day Nico was still working with ink and a blank page, so I’d say the challenges are the same: create the best story.

ROBLEDO: Tells us about the commercial challenges and how you were able to surpass some of them.

O’CONNELL: Certainly there would be no book tour, and we did have a couple magazines and a television program who were denied access to the prison, but Nico actually did a number of interviews with prominent places. Quil Lawrence’s on NPR being one of my favorites because he managed to get Nico reading on tape and broadcast that. Literally getting Nico’s voice into the world. The sound quality wasn’t great, but he did it. Overall it was rather amazing to see the kind of care and interest people took in Nico and the grace with which Nico handled it. I can’t even imagine that pressure and the mental will power it takes to do an interview and then sit in a cell thinking about it. I’m typing this on my phone and am nervous about it.

ROBLEDO: In what way has working with an incarcerated person helped you understand more about the system? Has your perspective changed?

O’CONNELL: Nico worked hard to take advantage of whatever resources he could and clearly that paid off. But if anything it only showed me there should be more. More access to books. More access to other means of self-expression. More access to visitors and other people. More access to phone calls. More ways to feel human.

ROBLEDO: Would you publish an incarcerated writer again? If so, what would you think about differently the second time around? What can others learn from your process?

O’CONNELL: Yes. Without a doubt. There’s not too much I would do different. I think the one thing that people don’t expect is the time it takes to pass information back and forth. You can’t email attachments, so you need to budget in time to send things like covers via regular mail and time for the prison to review and then pass them on to the author, and for the author to review them. We did ok with this, but it never hurts to plan ahead for that back and forth.

Like any other creative person they’ve entrusted you with their story and their work, and as an editor you have to be there for them. They’re writers, not prisoners.