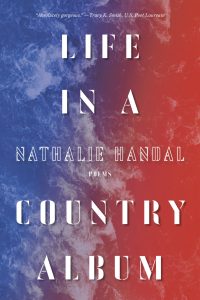

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Jared Jackson speaks with Nathalie Handal, author of Life in a Country Album: Poems (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2019).

1. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

1. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

As a Palestinian, I was told I exist and don’t exist, am real and imagined. I understood early on that truth is multilayered, complicated, and carried contradictions. Truth is not fully factual; fiction not fully invented. It is often difficult to differentiate fact from fiction under occupation, as reality can be surreal: A donkey might be arrested because it does not have the right paperwork, or a corpse might continue to be jailed because the prisoner died before the sentence was over. Poetry allows me to share truth with its personal and historical convolutions. I search for what happened, but more poignant to me, what were they feeling, what was omitted? I try to deliver truth that can’t be avoided even if you’ve become accustomed to the lie; it triggers doubt that is unyielding until you confront it.

2. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

Too many stories from displaced communities haven’t been told, so I am almost always inspired. But I agonize over the tension of time—that I will never get to all the voices and stories, to all I want to write. Language is always calling me—showing me how to see freedom; how to arrive to the worlds in the words, phrases, sentences I’ve collected; moving stillness and symphony into synchronicity. I love to wake up early to write when I’m in my apartment in Queens or Rome. On the road, I read a lot, and write in my notebook or in my mind. I take photographic notes. My camera is my other pen. I work on different projects at a time as they fuel each other. I give myself deadlines.

“Language is always calling me—showing me how to see freedom; how to arrive to the worlds in the words, phrases, sentences I’ve collected; moving stillness and symphony into synchronicity.”

3. What is one book or piece of writing you love that readers might not know about?

Metamorfosis del Jardín by Giovanni Quessep, who I am currently translating. He is a well-known Columbian poet of the Levantine diaspora who writes verses the way Gabriel García Márquez writes stories, with language that leaves us in infinite labyrinths. It tells us wandering is without end, and being is not a fable. You live the way you tell the tale, at the end of words. I also think the Sicilian writer Leonardo Sciascia, whose work questions power and the role of the writer in society, should be better known in the mainstream—books such as The Council of Egypt, Todo Modo, and Sicilian Uncles.

4. How can writers, and poets specifically, affect resistance movements?

Poetry can move our mind and heart so monumentally, that it reverses fear, discrimination, and prejudice. That’s why so many poets have been imprisoned and/or exiled. Poetry is on the side of truth. Writers point to issues that need to be resisted like racism, religious antipathy, and corruption. They have the ability to veer perspectives and influence individuals. A poem or story can galvanize people into action, or impact the aims of resistance movements.

5. What do you consider to be the biggest threat to free expression today? Have there been times when your right to free expression has been challenged?

The arrogance of power—using authority to discredit or intimidate people into self-censorship or silence. Our freedom of expression is being challenged more than ever. This current tendency to reduce facts to opinions and dismiss truth, alongside nationalism and nativism spreading on every continent, is critical. That said, freedom of expression never included all our voices. But society cannot just function successfully and progress without dependable news that includes us all. And we have to keep revisiting and reimagining all of it if we want it to last.

“My preoccupations and the questions in my writing are formed by my identity: born in the Caribbean but not entirely from there; Latin American but not entirely, European but not entirely, Asian but not entirely, Middle Eastern but not until my adult life could I say Palestinian without distress; a French and American citizen but always being asked where I come from originally. Why couldn’t I be entirely from all these places, including their literary spaces?”

6. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity?”

Writing drew me into visibility, so I can’t separate my identity from my writing. Growing up, there were limited spaces where I could say who I am and where I’m from, for fear of being discriminated or thrown out. These memories shaped my understanding of power and the world. My preoccupations and the questions in my writing are formed by my identity: born in the Caribbean but not entirely from there; Latin American but not entirely, European but not entirely, Asian but not entirely, Middle Eastern but not until my adult life could I say Palestinian without distress; a French and American citizen but always being asked where I come from originally. Why couldn’t I be entirely from all these places, including their literary spaces? What does entirely mean? Why is the most fundamental aspect of my globality overlooked? This multiplicity was born out of what was taken away from me, out of the absence of choice. Writers such as June Jordan, Adrienne Rich, and Audre Lorde reminded me that though I don’t have the luxury of forgetting my identity, I don’t have to be trapped in other people’s fantasies. I am human first, and I define myself.

7. Your recent poetry collection, Life in a Country Album, explores sincerely nuanced questions about identity and place, and what the two mean to the individual. As a writer with a multifaceted background—having lived in Europe, the Arab world, Latin America, and the United States—what does the idea of “country” mean to you? How did you set out to interrogate its meaning in the collection?

7. Your recent poetry collection, Life in a Country Album, explores sincerely nuanced questions about identity and place, and what the two mean to the individual. As a writer with a multifaceted background—having lived in Europe, the Arab world, Latin America, and the United States—what does the idea of “country” mean to you? How did you set out to interrogate its meaning in the collection?

Country, like beauty, can be a wound. It is unsafe and safeguarding. It showed me the fright and ferocity in hearts. In the name of country, people have tortured and massacred other people without ever exchanging a glance or a word with them. Yet, we all seem to need or want to belong to a country—whether our reasons are ancestral, ideological, primal, patriotic, or practical. I’m interrogating in this collection if we love a country, how we love it, and perhaps most importantly: Does it love us?

Our obligation should not be to a country but to each other, all over the world. That’s one way a country can cease being a wound. My ideal country is a poem full of people I’ve inhabited, languages I’ve flirted with, seas I’ve seduced, and skies I’ve been tempted by.

8. Why do you think people need poems? What can poems do, particularly in times like this, when millions of lives are disrupted and the future is uncertain?

Poems remind us we will survive. They record, transform, and empower. They recount back to us our memories, miseries, and magics. They are echoes engaging us, encouraging us to step out. They create spaces for coexistence. No borders exist for a poem. Poems take us farthest in the smallest space, take us to the bravest side of love, and express emotions that dare language. A poem is the music of mystery, and until we embrace mystery, we can’t fully be.

“Poems take us farthest in the smallest space, take us to the bravest side of love, and express emotions that dare language. A poem is the music of mystery, and until we embrace mystery, we can’t fully be.”

9. In the poem “Cara Aceitunada,” a man in Granada says, “the mirrors of history / confuse history / but in your olive-colored face / no one can disturb your heart.” How do these lines speak to discomfort of both dislocation and belonging that permeates the collection? How is solace achieved?

Solace is achieved through poetry, which defies history and occupation, and transcends time. It might not be enough for those of us who are displaced—as everyone has the right to the freedom of choice—but it is powerful.

10. In a recent article in the Chicago Review of Books, Sarah Blake interviewed poets to find out how they decided what the final poem in their collection should be. The final poem in Life in a Country Album is titled “Eleutheria,” which is noted at the bottom of the page to mean “freedom” in Greek. After navigating the reader through a powerful journey of self-exploration, grappling with our world and our understanding of home, what made this the appropriate poem to end the collection?

I wanted to close with an opening. Epic and echoing. It is one of the last poems I wrote and conveys what I want readers to take away—that despite the trauma or struggles, hope is enduring, and we can reset our wings, piece lost albums of separated worlds.

Nathalie Handal’s recent poetry books include Life in the Country Album (University of Pittsburgh/flipped eye publishing, United Kingdom 2020), a finalist for the Foreword Book Award; the flash collection The Republics, lauded as “one of the most inventive books by one of today’s most diverse writers,” and winner of the Virginia Faulkner Award for Excellence in Writing, and the Arab American Book Award; the critically acclaimed Poet in Andalucía; and Love and Strange Horses, winner of the Gold Medal Independent Publisher Book Award. She is the author of eight plays, editor of two anthologies, and her creative nonfiction has appeared in Vanity Fair, Guernica Magazine, The Guardian, The New York Times, The Nation, The Irish Times, among others. Handal is the recipient of awards from the PEN Foundation, the Lannan Foundation, Centro Andaluz de las Letras, Fondazione di Venezia, among others. She writes the literary travel column “The City and the Writer” for Words Without Borders.