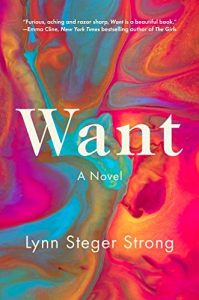

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Jared Jackson speaks with Lynn Steger Strong, author of Want (Henry Holt and Co., 2020).

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

I read Mrs Dalloway and To the Lighthouse in quick succession my sophomore year of college. I don’t think I breathed the whole time. It felt like suddenly being shown that I was allowed both as a human and a writer, that words and stories could be more even than I had thought they were.

2. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction? The thing that feels “true” to me about fiction is that it has no obligation to make an argument. I don’t believe in the “truth” of arguments. They’re too couched in an agenda, too shaded by a subjectivity we can never wholly have access to. (This is not the same, to be clear, as the rightness or morality of certain arguments, which I believe in fully.) But, stories, I would argue, force readers to look and see and come to their own conclusions, to reconsider arguments they might consider predetermined. I’m not sure I believe in any sort of fixed truths, but I think well-shaped fiction can get us closer than most other things. I think it’s an opportunity to pose questions more than answer them. In this context, I think of my job is looking and seeing as well and as broadly as I can, and then shaping those observations in ways that hopefully help readers to look and see as well.

“The thing that feels ‘true’ to me about fiction is that it has no obligation to make an argument. I don’t believe in the ‘truth’ of arguments. They’re too touched in an agenda, too shaded by a subjectivity we can never wholly have access to. . . But, stories, I would argue, force readers to look and see and come to their own conclusions, to reconsider arguments they might consider predetermined.”

3. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

Very early mornings. It started when my kids were babies, and I realized the sort of magic of all the non-time when they—and therefore I—was awake, but no one else was. How secret and special that time felt, similar, I think, to riding a train or walking somewhere—these pockets when you don’t feel obligated to interact or clean the kitchen or listen to the news, and your brain feels looser and more malleable. For years, I wrote on my phone while they were nursing, and then, once they (finally) started sleeping, I just kept that time. I don’t always use it for writing. I use it for running, reading, or staring out the window. My main rule for getting work done is to be merciless in terms of making time to try to do it, but then within that time, to be merciful with regard to how I spend that time.

4. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

I’m trying to finalize my syllabus for a class I’m teaching on “Unhinged Narrators,” so, I just finished Knut Hamsun’s Hunger and am about to start, on a friend’s recommendation, Tope Folarin’s A Particular Kind of Black Man.

5. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity?”

There’s this great Richard Rodriguez quote from his essay “The Third Man” in which he talks about what he envies most about whiteness is the blankness, the “arrogance and confidence,” to be anything. “I grew up wanting to be white,” he says. “That is, to the extent of wanting to be colorless and to feel complete freedom of movement.” I think about that a lot, both in terms of wanting to consider the experiences of my characters in the context of a larger conversation, but also in terms of being cognizant of all the things I can’t and do not see. A friend of mine said to me a few months ago, “Anyone who thinks any of your characters are anything but a product of a single brain doesn’t understand how writing works.” I don’t think anything I write is not informed by the fact that I move through the world as a woman and as a mother—as a particular individual with a particular set of experiences and encounters and ideas. Perhaps the best advice I’ve ever gotten with regard to writing is to make the thing that only you could make.

“I don’t think anything I write is not informed by the fact that I move through the world as a woman and as a mother—as a particular individual with a particular set of experiences and encounters and ideas. Perhaps the best advice I’ve ever gotten with regard to writing is to make the thing that only you could make.”

6. What is the most daring thing you’ve ever put into words? Have you ever written something you wish you could take back?

I wrote this column for The Guardian about money for a while, and I’m very glad I did it. I think we have to be more open and more honest when talking about money. It’s a lot of what want is about as well. But every time one of the essays went live, I spent most of the day sort of shaky and shame-faced; it felt like I’d done something deeply wrong or reprehensible, which, (1) I think is further to the point of all the ways that the particularly pernicious force of capitalism pervades our bodies long after we reject the premise, and (2) I hope is an argument for the fact that maybe I’d said something worth saying?

7. What advice do you have for young writers?

Just keep going. Take risks, get messy. Read and read and read—use that reading to find and create language for what it is you want to make, so that when you make it, as you’re working to make it better, when you start to get feedback, you have a solid enough relationship with it that you can stand up for it and push it further toward being what you want, even if and when others decide that it should be something else.

8. Which writers working today are you most excited by?

This feels like cheating, but one of my dearest friends is also one of my favorite writers: Rumaan Alam. It is a sort of specific and extraordinary privilege to get to share work and talk about work with someone who feels like they’re reaching for something similar to what you’re reaching for. I also really love Han Kang, Paul Beatty, Lydia Davis, Deborah Eisenberg, Bryan Washington, Rufi Thorpe, Vigdis Hjorth, and Samantha Hunt.

“I think what feels so scary right now to so many people, but also like a relief, is that it has become so clear that the idea that most things are ‘earned’ or ‘deserved’ in this country, in either direction, is pretty patently absurd.”

9. The title of your new novel is Want. For me, this meaning of “want” is equal to—if not more about—the lack of something, a deficiency, than the desire for something. How did you approach portraying the nuance of the word? How did the narrator’s friendship with another woman allow you to express the exhaustion so rarely afforded to women who appear to have “checked off certain boxes” deemed as indications of success by society?

9. The title of your new novel is Want. For me, this meaning of “want” is equal to—if not more about—the lack of something, a deficiency, than the desire for something. How did you approach portraying the nuance of the word? How did the narrator’s friendship with another woman allow you to express the exhaustion so rarely afforded to women who appear to have “checked off certain boxes” deemed as indications of success by society?

I talked a lot with my agent about Joan Silber’s novel Improvement, and how throughout that book, the word just churns and churns in your brain as you interact with different characters and see them muddle through their lives. I love what you say about a lack here, because I think this book is very much about the sort of gradations of wanting and getting, for whom that is allowed, and on what terms and at what cost—the particular frustrations of being told over and over you can and should want, but then being continually shown the opposite.

Like you say, I’m informed by my identity in ways that I think I still probably don’t wholly understand, but one particular space that interested me here is the type of white woman who is—in so many ways—safe and cosseted, who her whole life has been told she can have and be anything she wants, to follow her dreams, but who has in many ways been sold a faulty set of goods. I think Elizabeth’s friendships, both with Sasha and with the other women in the book, gave me space to show the different ways that those unattainable wants manifest themselves and harden into something else as we grow up.

10. Your novel feels uncannily timely. More than two-thirds into it, Elizabeth says, “We cannot live outside the systems and the structures, but, it turns out, I cannot live within them anymore either.” In what ways does Elizabeth’s life and struggles reflect the imbalances in our system that have always been present, but have been made more vivid due to the pandemic and social unrest of recent events?

You know, pre-COVID, there was this string of Goodreads reviews—I know I shouldn’t read them, but I do—in which readers were calling Elizabeth “depressed.” She has struggled with depression in the past, but I would argue what she is, for most of the present action of the novel, is worn down by a system that has created very few avenues through which she might be able to sustain herself. There were these responses to my Guardian column, too, where people would pick out certain admissions: that I feel too tired to take a fifth job, that I choose to live in New York City, to affirm for themselves that my life was my fault and not because of larger structural failures.

I think both I and Elizabeth are wholly cognizant not only of all the ways we’re culpable in—and embarrassed by—the ways our lives haven’t turned out as we thought that they might, but also of our obscene advantages within these systems. But, I think my goal in both was to show how patently absurd the narrative of “personal responsibility” is. I think what feels so scary right now to so many people, but also like a relief, is that it has become so clear that the idea that most things are “earned” or “deserved” in this country, in either direction, is pretty patently absurd.

Lynn Steger Strong’s first novel, Hold Still, was published in 2016. Her nonfiction has appeared in The Paris Review, Guernica, LARB, Literary Hub, and elsewhere. She teaches writing at Catapult and Columbia University.