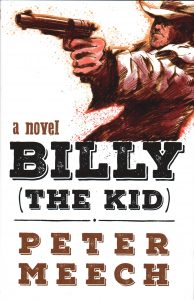

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Jared Jackson speaks with Peter Meech, author of Billy (the Kid) (Sentient Publications, 2020).

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

Before I was a reader, I was a listener. My father was the Scheherazade of our family, and every night, he would regale us with tales he spun out of thin air. Some of the tales began and ended in a single night. Others became sagas that continued for weeks on end. The first book that had a profound impact on me was Bennet Cerf’s Book of Laughs. My brother used the book to teach me how to read. With his help, I sounded out every word on each page. To this day, I remember all the jokes in the book. And I remember the oversized pages. There was a certain weight to them, and they made a rustling and cracking sound when I turned them.

2. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

Can we skip this question? And retitle this article The PEN Nine Interview? Because I really don’t know where my ideas come from. And I don’t have the faintest idea of how my creative process works. All I can say is this: Once I’m in the grip of an idea, it will haunt me for weeks, months, or even years until finally I have to do something about it. And when that moment arrives, I make an outline of the story—the more detailed, the better. But it doesn’t mean I won’t adjust the outline as the writing progresses.

Once you begin to understand your characters, their backstories, their motivations—both hidden and apparent—new plot possibilities begin to emerge, and you suddenly realize you are no longer in control of the writing process. Something beyond your surface consciousness is guiding you, and your job is to step out of the way. For inspiration, I keep on my nightstand a very old copy of The Poetical Works of John Keats, whose stiff covers, or boards, are held together by a thick rubber band. My grandfather gave me the book when I was a teenager. He bought the book when he was a teenager and for many years kept the book on his nightstand.

“Once I’m in the grip of an idea, it will haunt me for weeks, months, or even years until finally I have to do something about it.”

3. What is one book or piece of writing you love that readers might not know about?

The Autumn of the Patriarch by Gabriel Garcia Marquez. It’s a virtuosic piece of writing by a prose master at the top of his game. Marquez once described the book as a “poem on the solitude of power,” and it does read more like a poem than a novel. There are gorgeous sentences that go on for days without a single period in sight.

4. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

The last book I read was Sylvia Cranston’s H.P.B. The Extraordinary Life and Influence of Helena Blavatsky: Founder of the Theosophical Movement. Madame Blavatsky is not well-known in America today, though she’s still revered in her native Russia. Her book The Secret Doctrine, published in 1888, and subtitled The Synthesis of Science, Religion and Philosophy, influenced many scientists, composers, artists, and writers in the early part of the 20th century. Among the writers who drew inspiration from her ideas were W. B. Yeats, George W. Russell (AE), James Joyce, E. M. Forster, Jack London, D. H. Lawrence, T. S. Eliot, Thornton Wilder, and L. Frank Baum. Right now, I’m rereading Ernest Hemingway’s The Nick Adams Stories. And alongside it, I’m reading William Burrill’s Hemingway: The Toronto Years, which includes 25 “lost” news stories and features that Hemingway wrote as a journalist during his four years in Toronto. Observing the young Hemingway hone his craft in the early 1920s is a masterclass in prose writing. It would be two years after Hemingway left Toronto before he published The Sun Also Rises.

5. What is your favorite bookstore or library?

Who wouldn’t want to visit the Library of Alexandria if it still existed? When Julius Caesar was chasing Pompey into Egypt, he set the ships on fire in the harbor, and the fire spread to the library. But only part of the library was destroyed, and later it was rebuilt. The library’s real destruction began with government defunding during the Roman Period some 250 years after Caesar’s civil war.

Defund the arts, and society decays.

“In my novel [Billy (the Kid)], I wanted to demystify and deglorify violence, explore the protean nature of identity, and write about transcendence—a topic that has almost disappeared from secular literature today.”

6. What advice do you have for young writers?

Read widely and out of your field of interest. Find your own voice.

7. Which writer, living or dead, would you most like to meet? What would you like to discuss?

I’m a great admirer of the metaphysical fantasies of Jorge Louis Borges. Borges believed in other dimensional realities, and most importantly, in the magic of language. For Borges, literature was a portal to the perils of the human condition. At heart, he was always a writer of wisdom. And wisdom, as Walter Benjamin famously said in the 1930s, is in decline. When Borges waxed philosophical, everything he said was unexpected and insightful, so any serious discussion with him would have the force of a revelation.

8. A main concern of the protagonist in your novel, Billy (the Kid), is reclaiming his narrative. What drew you to Billy the Kid and his story? Why did you want to reframe the narrative of one of the famous outlaws of the Wild West?

8. A main concern of the protagonist in your novel, Billy (the Kid), is reclaiming his narrative. What drew you to Billy the Kid and his story? Why did you want to reframe the narrative of one of the famous outlaws of the Wild West?

To talk about why I wrote Billy (the Kid), I have to talk about my mother. She was a fifth-generation Coloradoan and was born in Pueblo, Colorado, where the novel is set.

As a child, she met a retired dentist who claimed to have been a famous outlaw in his youth. On special occasions, he would wear his Colt Double-Action Thunderers, the same guns favored by Billy the Kid. Who was this dentist? A former outlaw? Or a hopeless dreamer? The central mystery of this man’s life became the point of origin for my novel.

I wrote my novel to tell his story, but also to challenge the tropes of the traditional Western novel. And what better way to do that than to reframe the narrative of one of the most storied outlaws of the West? In my novel, I wanted to demystify and deglorify violence, explore the protean nature of identity, and write about transcendence—a topic that has almost disappeared from secular literature today.

“I have to say the novel is first and foremost a conversation with my mother, who embodied many of the values and virtues we associate with the West. . . I could quote a dozen examples of how my mother’s suggestions helped with the historical accuracy of the story. And historical accuracy, as we know, adds immeasurably to the verisimilitude of a story.”

9. A quarter of the way into the novel, the narrator says, “Truth is a strange thing. There’s the truth and there’s what people believe is the truth, and sometimes what they believe is stronger than the real truth and sometimes it’s even truer than the real truth.” What is the relationship between truth and fiction? How can language reveal or obscure truth?

Ever been to an art gallery, fallen in love with a painting and then read the artist’s statement, and wished the artist hadn’t said a thing? In the same vein, I’d rather not expand on the narrator’s quote. We lose pithiness when we labor to explain.

10. The novel is dedicated to your mother who was born in Colorado “and who loved the West.” There’s been a wave of new fiction amplifying voices of the West. As this book is in part about legacy, how is it in conversation with the mythology of the West?

I have to say the novel is first and foremost a conversation with my mother, who embodied many of the values and virtues we associate with the West. In an early draft of the story, I had a character eating a lamb chop with mint sauce. When my mother read the manuscript, she crossed out “mint sauce” and wrote “mint jelly,” explaining that in Depression-era Pueblo, only mint jelly was available. Naturally, I made the correction. In the margin of another page, she wrote “meadow lark,” and when I asked her about the note, she talked about how much she loved observing meadowlarks as a young girl in Pueblo, and could I put one in the story? So, of course, I put a meadowlark in the story.

I could quote a dozen examples of how my mother’s suggestions helped with the historical accuracy of the story. And historical accuracy, as we know, adds immeasurably to the verisimilitude of a story. Setting the story in 1932 was, in itself, a direct challenge to the mythology of the West because my story revolves around a bootleg war, rather than, say, a range war. I also people the story with characters from diverse backgrounds not often found between the covers of a traditional Western novel. And these characters, in their very diversity, challenge the mythology of the West. As more and more stories are written about the West in different time periods and from the perspectives of different cultures, we’re beginning to realize that we can’t speak any more about the American West. We can only speak about American Wests.

Peter Meech is an author, screenwriter, director, and producer. His memoir, Mysteries of the Life Force: My Apprenticeship with a Chi Kung Master, has been translated into several languages. He has an MA in communications from Stanford University, where he won a Stanford Nicholl writing award.