The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, in celebration of Women in Translation month, PEN America’s Public Programs Manager Lily Philpott speaks with Ha Seong-nan, author of Flowers of Mold (Open Letter Books, 2019). Translated from the Korean by Janet Hong.

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

어둠 속을 혼자 걸은 적이 있었다. 외지고 으슥한 산골 마을이었다. 길은 산과 계곡을 끼고 구불구불 이어졌다. 삽시간에 어둠이 내 눈과 코, 귀를 고무마개처럼 틀어막았다. 나는 내 발짝 소리에도 가슴을 졸였다. 어둠이 손을 내밀어 내 머리채를 채어감을 듯했다. 손전등 불빛 안의 가시거리가 너무도 짧아 뛸 수도 없었다. 대학의 지도교수인 오규원 선생님의 심부름이었다. 무섭다고, 남자애들을 두고 왜 내게 다녀오라는 거냐고, 선생님에게 말하지 못했다. 마을의 이장집까지는 걸어서 십여 분 남짓. 그러나 그날 밤 시간은 다르게 흘러갔다. 선생님이 돌아가신 뒤에야 선생님의 시 (오규원, , 문학과지성사)를 읽게 되었다. 막연하게나마 선생님도 어느 밤 그 어둠 속을 혼자 걸었다는 걸 알게 되었다. “어둠을 자세히 보는 방법은 뭐니 뭐니 해도/어둠이 어두운 게 아니라/어두운 게 어둠이라는 사실이다.” 혹시 그때 선생님은 삼십 년 뒤 내가 처해 있을 상황을 미리 짐작한 건 아니었을까. 어둠 속을 헤매는 것과 같은 나날을 보내게 될 거라는 걸 짐작한 건 아니었을까. 그래서 그 어둠 속을 미리 걷게 한 것은 아니었을까. 간결하고도 장난스러운 싯구. “어둠은 자세히 봐도 역시 어둡다.” 이 한 문장은 마치 내가 글을 익혀 처음 더듬더음 읽은 문장인 양, 이 시절을 함께 지나고 있다.

I once walked in deep darkness all alone, along a path through a remote mountain village. The path snaked through the woods and valleys. In no time, darkness plugged up my eyes, nose, and ears like a rubber stopper, and my blood froze even at the sound of my own footsteps. It seemed the darkness would reach out and snatch at my hair. But I couldn’t even run, since my flashlight illuminated only a short distance ahead. Professor O Gyu-won, my university advisor, had sent me on an errand, and I hadn’t been able to say that I was scared, or ask why he’d picked me to go, instead of one of the male students. The village head’s house was about 10 minutes away on foot, but that night time flowed differently.

It was only after Professor O’s death that I happened to read his poem “Darkness is Dark, Even After a Good Hard Look” (Eodumeun jasehi bwado yeoksi eodupda). Somehow I knew that one night he had also walked through that same darkness all alone.

Talk all you want about the proper way to look upon darkness,

but it’s not darkness that’s dark.

What’s dark is darkness and that’s the truth.

Did he perhaps sense, even then, the situation I’d be in 30 years later? Where I’d spend my days as if groping through darkness? Was that why he’d had me walk through that deep darkness ahead of time? “Darkness is Dark, Even After a Good Hard Look.” This concise, playful little line. Like the first sentence I ever read or uttered, it has stayed with me through the years.

2. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

소설가는 아이러니하게도 거짓말을 하는 사람이다. 가끔 소설의 주인공과 소설을 쓴 작가를 혼동하는 독자들도 있지만 대부분의 독자들은 소설이라는 장르를 통과한 이야기를 허구로 읽는다. 그러나 소설은 현실과 동떨어진 이야기가 아니어서 소설가들은 오늘도 ‘진실된 이야기’를 쓰려고 노력하고 있다. 진실된 이야기라니. 이 또한 아이러니하다.

요즘 내가 생각하고 있는 것은 ‘호주머니 속의 돌멩이’이다. 내가 만난 한 엄마는 트레이닝복의 상의 호주머니 속에 돌멩이를 넣어 다녔다. 자신의 아이에게 위협이 가해지면 언제라도 돌멩이를 던질 참으로 호주머니 속의 돌멩이를 꼭 쥐었다.

그 아이는 운이 좋은 아이였다. 어릴 적 사고를 당했지만 크게 다치지 않았고 평상시라면 지원률이 높아 가기 어려웠을 고등학교에 입학까지 하고 결국 그날 그 배에 탔다. 2014년 4월 16일 바다에 잠긴 그 배에 아이를 밀어넣은 것은 아이러니하게도 행운들이었다.

나는 그 아이의 엄마가 그랬듯이 호주머니 속에 손을 넣어 그 돌멩이를 꼭 쥐어본다. 쥐어보는 상상을 한다. 그러나 그 엄마의 마음을 안다고 말할 수 없다. 알 수 있을 것 같다고 말할 수 없다. 소설은 현실을 거짓말로 옮기는 일인데, 잘 되어봐야 ‘진실된 이야기’인데, 설득력을 가지지 못한 이 현실을, 어떻게 허구로 담아낼 수 있을까.

Ironically, a fiction writer is someone who deals in lies. Some readers confuse the protagonist in a fictional work with the author of the work, but most readers are willing to accept what falls under the genre of fiction as fictitious. However, because fiction cannot be separated from what is real, fiction writers still strive to tell stories that are true. Now what do I mean by “stories that are true”? Isn’t this also ironic?

These days, I constantly think about the “rock in the pocket.” A mother I know used to walk around with a rock inside the pocket of her tracksuit jacket. She’d kept her hand around the rock at all times, ready to hurl it at the slightest threat of danger to her child.

This child was lucky. Though he was involved in an accident when he was younger, it was minor, and he even gained admission to a competitive senior high school notoriously difficult to enter, but in the end, on that fateful day of April 16, 2014, he boarded the Sewol ferry. Ironically, it had been a series of fortunate instances that had put him on that ferry.

Just as his mother had, I reach into the pocket and wrap my hand around the rock. I imagine tightening my hand around it. But I can’t say I know how the mother feels. Neither can I say I think I know how she feels. Fiction is turning what’s real into lies (or in the best case, what’s real into “stories that are true”), but how are we to fictionalize this reality that seems, at times, more unbelievable than life itself?

“To me inspiration means to catch the words—random words with zero context—spewed by those living this moment with me.”

3. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

식당의 식탁들 사이는 간격이 좁고, 점심 시간 한번에 손님이 몰릴라치면 합석을 하게 될 때도 있어서, 나는 자연스럽게 그들이 나누는 대화를 듣게 된다. 떠들썩한 식당이 한순간 고요해지고 어느 식탁에서 긴 여행을 마치고 돌아온 누군가가 일어나 한 편의 멋진 이야기를 들려주는 일은 당연히 일어나지 않는다. 다만 나는 삼십여 분의 식사 시간 동안 내 두 귀를 활짝 열어놓는다. 드문드문 날아오는 단어와 문장들. 고개를 들고 그 말을 한 사람의 표정을 살필 수도 궁금한 것을 물을 수도 없다. 다만 내가 하는 일은 앞뒤가 잘린 문장을 완성하려 애쓰는 일이다. 장소는 식당에서 버스 정거장으로 다시 전철 안으로 계속 바뀐다. 나에게 영감이란 나와 함께 이 순간을 살아가는 이들이 툭 내뱉는 그 맥락 없음의 포착이다. 나의 많은 단편소설들은 이렇게 시작되었다.

There are times I get to listen in on strangers’ conversations, because the tables at a restaurant are too close together or because I have to share a table during the lunch rush. Of course, the restaurant noise never grows dim and people never get up from their seats to tell wonderful tales about the long journey from which they have just returned. I simply keep my ears open for the next half an hour while I eat. From time to time, words and phrases drift over. I can’t look up to study the expression of the speaker, and neither can I ask questions to satisfy my curiosity. All I can do is attempt to complete the phrases that have had their heads and tails lopped off. The setting changes all the time, from a restaurant to a bus station to a subway car. To me inspiration means to catch the words—random words with zero context—spewed by those living this moment with me. Many of my short stories have begun this way.

4. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

작년 12월호의 문예지에 실릴 소설을 고민하다가 12월이니 12월이 물씬 느껴지는 소설을 써보면 어떨까라는 데 생각이 미쳤다. 그러자 크리스마스와 함께 몇몇 작가들의 글이 떠올랐다. 그 중 하나가 헨리 제임스의 소설 이었고 반년이 흐른 한여름에 그 소설을 꺼내 수정하게 되면서 도 다시 꺼내들었다. 수도 없이 읽었지만 본격적인 이야기가 시작되기 전 화자의 입을 통해 드러나는 ‘나사의 회전’에 관한 부분, “아이가 이야기에 나사를 조여주는 역할을 준다고 한다면 두 아이가 등장하면 어떻겠습니까.” “그야 두 아이들이 나사를 두 번 조여준다고 말할 수 있겠지요”라는 부분에서 매번 내 안의 속물성을 들키고 만다. 나사가 회전하면서 구멍을 파고들 듯 모호함와 공포감이 조금씩조금씩 조여들어오는데, 가정교사인 ‘나’의 이야기에 나는 10년 전이나 지금이나 매번 속절없이 빠져든다. 일인칭 시점의 믿을 수 없고 뒤틀린 화자인 ‘나’의 고백을 아무런 의심 없이 받아들여, 시선에 따라 달라지는 전혀 다른 결말에 대해 아직도 공감하지 못하고 있다. 여간 곤란하지 않다. 소설을 수정하고 있는 당분간은 이다.

Last year, I was thinking about what to write for the December issue of a literary journal when I had the idea to do a story that would capture the spirit of December. Of course, Christmas came to mind, along with the works of several writers. One such book was Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw. In the middle of the summer of the following year, when I started revising my story to expand it into a novella, I also pulled out The Turn of the Screw from my shelf. Though I’ve read it numerous times, whenever I come to the part in the prologue when the narrator talks about “the turn of the screw,” I confront once again the fact that I’m so easily manipulated:

“ . . . If the child gives the effect another turn of the screw, what do you say to TWO children—?”

“We say, of course,” somebody exclaimed, “that they give two turns! Also that we want to hear about them.”

Little by little, as the screw turns and burrows deeper, tightening my sense of doubt and horror, I still find myself, even 10 years later, falling under the spell of the governess’s first-person narrative. I’m willing to accept without question the story as told by this unreliable narrator, to the extent that I still cannot agree with the other interpretations of this novella. But no matter. The Turn of the Screw will be the only thing I’ll read for the next bit, at least while I’m in the midst of revisions for my novella.

5. What do you consider to be the biggest threat to free expression today? Have there been times when your right to free expression has been challenged?

한 해에 발표된 단편소설들을 읽고 이야기를 나눌 자리가 있었는데, 그때 한 소설에 대한 감상을 이야기했다가 나중에 지극히 남성중심의 시각에 갇힌 편협한 평가라는 말을 듣고 말았다. 나는 가끔 소설 속 인물의 성별을 중요하게 생각하지 않는 버릇이 있어 그 소설에서도 계속 변명을 늘어놓는 남자의 이야기를 한 인간의 이야기로 읽었다. 따끔한 소리를 듣고나서야 변화를 감지하는 일에 둔했다는 걸 깨닫게 되었다.

2017년 배우 알리사 밀라노가 트위터를 통해 제안한 ‘미투 해시태그(#MeToo)가 빠르게 확산되고 많은 이들이 연대 의지를 밝혔다. 늘 생각만 하고 있던 이야기를 글로 써야겠다고 마음먹은 것도 이 일과 무관하지 않을 것이다. 용기를 내야겠다고 별렀는데 그 사이 또 시간이 흘렀다.

이십 년 전 나는 꿈에 대한 이야기를 짧은 소설 형식으로 여러 편 발표했다. 개인적인 변화가 있은 뒤로 자연스럽게 꿈 이야기는 쓰지 않게 되었는데, 그때부터 사실 내가 꾼 꿈 중에 글로 쓰고 싶은 이야기들이 생기기 시작했다. 하지만 두렵고 부끄러웠다.

올해 초, 비로소 쓸 수 있겠다고 생각하고 시작했지만 욕심이 컸는지 마무리하지 못하고 말았다. 발표를 하고 혹시 그 소설을 읽은 누군가가 “이건 작가의 경험에서 나온 이야기인가요?”라고 물었을 때를 대비해 “이건 소설입니다”라고 발뺌할 구실도 마련해두었는데 말이다. 일어나지 않았지만 나는 늘 그 일을 상상하고 두려웠다. 그 공포에 대해 나는 곧 쓸 것이다.

I had the opportunity to read and discuss several works of literature that were published one year. When I shared my thoughts on a particular work, I was accused of being narrow-minded and interpreting the work from a male-centered perspective. Whenever I read something, I have the habit of not paying too much attention to the gender of a character, so even in this case, I’d interpreted the account of the male character, who continued to make excuses for himself, as simply the account of one human being. It was only after I received that reprimand did I realize I’d been too dull to detect the changing of the times.

In 2017 on Twitter, actress Alyssa Milano’s #MeToo hashtag went viral and many people expressed their solidarity. This isn’t unrelated to my decision to write about something I’ve been brooding on for a long time. I’d planned to take courage, but time passed once more.

Twenty years ago, I published several short stories about a dream I’d had. Ever since there was a change in my personal circumstance, I have naturally stopped writing about this dream, but to be honest, from that point, there were many dreams I wanted to turn into stories. But I was afraid and embarrassed.

At the beginning of this year, I started the project, thinking I could finally write this thing, but perhaps I was too ambitious, because I couldn’t finish it. Despite the fact that I had already prepared my response after publication (“This is fiction”) if anyone were to ask about the truthfulness of the story (“Is this story from the author’s own experience?”). This never happened, but I imagined the scene and was afraid. However, I’m resolved to write on that terror very soon.

6. What advice do you have for young writers?

오백 년을 산 의 이야기를 쓰기 시작하면서 좋은 소설을 쓰려면 오백 년을 살아야 한다고 생각하게 되었다. 역사는 되풀이 되고 삶의 패턴 또한 크게 바뀌지 않을지 모른다. 그래도 그쯤 살면 뭔가 알게 될지도 모른다.

앞서 발표된 소설들을 답습하고 있을지도 모른다. 하루 아래 새로운 건 없어, 라고 투덜댈 수도 있을 것이다. 그래도 소설을 쓰려면 한 오백 년은 살아야 한다고 생각한다. 뛰어난 직관이란 다양한 삶의 경험담일 수 있으니까. 그러나 오백 년을 산 소설가라도 해도 지금 당장은 글을 쓰기 위해 의자에 앉아야 한다. 그렇게 오래 살았음에도 다른 방법은 없다. 가장 중요한 것은 엉덩이, 오백 년 동안 의자에 앉아 있었던 그 엉덩이의 기억으로 오늘도 소설을 써야 한다. 오백 년이나 살았음에도 불구하고 가장 중요한 것은 엉덩이, 바로 엉덩이의 힘이다.

As I began to write Fox Woman, which is about a gumiho—the nine-tailed fox in Korean folklore—who has lived for the past five hundred years, I began to believe that you need to live five hundred years to write a good book. History would then repeat itself, with patterns of life changing very little, and perhaps I would actually learn something.

I might copy the books that had already been published. I might grumble: There’s nothing new under the sun. Still, I believe it takes about five hundred years to write a good book, since a variety of life experiences will give you an excellent instinct. But even a writer with five hundred years of experience has to sit in a chair in order to write. There’s no getting around it. It’s your rear end that’s most important; you must write using its memory of sitting glued to your chair, day after day, for five hundred years. In the end what’s important is your ability to sit in your chair; it comes down to the strength of your rear end.

“When I read, I can’t help but look at the work from both the reader’s and writer’s perspective.”

7. Which writers working today are you most excited by?

너무도 많다. 소설을 읽을 때면 어쩔 수 없이 독자이면서 작가의 입장이 된다. 어떤 소설은 독자인 것을 행복하게 하고 어떤 소설은 자꾸 독서를 멈추고 새로운 이야기를 시작하라고 부추긴다. 고백하건데, 그 작가들의 소설이 없었다면 나는 어떤 소설도 쓰지 못했을 것이다.

There are too many to mention. When I read, I can’t help but look at the work from both the reader’s and writer’s perspective. Some books make me glad to be a reader, and some prompt me to stop reading to begin a new story of my own. I have to confess, if not for the works of these writers, I would not have been able to write a single word.

8. Which writer, living or dead, would you most like to meet? What would you like to discuss?

지금 당장 스쳐지나가는 작가들의 이름이 너무도 많지만, 일단 내가 좋아하는 작가와는 통역 없이 만나 이야기하고 싶다. 그렇다면 오랫동안 마음에 품고 있던 한국의 여성작가인 강경애(1907-1943)이다.

가난한 농민의 딸로 태어나서 일제강점기 시절 만주 등을 떠돌며 살았던 그녀가, 작가로서 여자로서 어떤 삶을 살았는지 미루어 짐작하는 일은 어렵지 않다. 다른 여성 작가들이 일상과 낭만적인 사랑에 집중하고 있었을 때, 그녀는 자신의 경험을 기반으로 한 치열한 소설을 썼다. 단편소설 에는 경악할 장면이 사실적으로 표현되고 있다. 종기에 쥐가죽이 특효라는 말에 어머니가 쥐를 잡아 아기 머리에 붙이고 말았다. ‘아가는 언제 그 헝겊을 찢었는지, 반쯤 헝겊이 찢어졌고 거기로부터 쌀알 같은 구더기가 설렁설렁 내달아오고 있다. 어머니가 와라 기어가서 헝겊을 잡아젖히니, 쥐가죽이 딸려 일어나고 피를 문 구더기가 아글아글 떨어진다. “아가, 아가 눈 떠. 눈 떠라 아가!”’ 구더기마저 흰 쌀알로 보이는 가난 그리고 무지. 매번 좌절되는 소박한 꿈. 비참함을 끝내 지켜보는 시선에서 삶의 의지가 읽힌다.

만나면 무슨 말을 꺼내야 할까. 나보다 60년 앞서 태어나 지금의 내 나이보다 훨씬 어린 나이에 병으로 죽은 불행한 작가. 그녀가 이야기를 꺼낸다면 오랫동안 들어주고 싶다.

Again, too many names come to mind at once, but more than anything, I would like to talk with my favorite writers without the aid of an interpreter. In that case, it would have to be the Korean feminist author Kang Kyeong-ae (1906-1944), whom I’ve cherished for a long time.

Given that Kang was the daughter of a poor farmer and lived in Manchuria during the Japanese occupation, it isn’t difficult to guess the kind of life she led as a woman and writer. While many female authors around this time were writing about the romantic and the everyday, Kang wrote a brutal novel based on her own experiences. In the short story “The Underground Village,” a shocking scene is depicted realistically. After being told that rat skin is effective in healing an abscess, the mother catches a rat and sticks it on her baby’s head:

The baby has somehow torn off her bandage, and white maggots like rice grains are crawling out of it.

“Oh, what has happened, what has happened!” The mother jumps to her baby and turns the bandage over. The rat skin falls off, and bloody maggots spill out everywhere.

‘Baby, open your eyes! Open your eyes, my baby!’*

A world of poverty and ignorance, where even maggots look like grains of rice. A humble dream that gets frustrated each time. These characters’ wretchedness attest to their will to survive.

If it were possible to meet Kang, what would I say to this author who was born 60 years before me, this unfortunate author who died from illness at an age much younger than I am now? I would be delighted to listen to her speak for as long as her heart desires.

*Kang Kyeong-ae, The Underground Village, trans. Anton Hur (London: Honford Star, 2018).

9. Why do you think people need stories?

허리를 굽히고 들어가면 활자들이 별처럼 쏟아졌다. 단순한 비유가 아니다. 1970년대 출판사의 영업부 직원이었던 아버지의 가방에는 책 판매를 위한 팸플릿이 잔뜩 들어 있었다. 그것이 쓸모없어지자 아버지는 그 팸플릿으로 우리가 놀던 다락방의 천장과 벽에 도배를 했다. 그곳에는 수많은 작가들의 수많은 책들에 대한 간략한 소개가 있었는데, 하나같이 궁금한 대목에서 끝나 있었다. 나는 단순히 그 책들의 결말이 궁금해서 책을 읽게 되었다. 그리고 그 이야기들 대부분이 실패에 관한 이야기라는 것을 알게 되었다. 그 이야기를 읽고 자란 나는 지금 또다른 인물의 실패담에 대해 쓰고 있다. 이야기는 한 인간의 실패에 관한 것이고 독자들이 책을 펼치고 실패에 낙담하고 한편 안도하는 한 이야기는 계속될 것이다.

When I stooped through the doorway of the small attic where we played, the Korean alphabet gushed down like stars. This isn’t an analogy. In the seventies, my father worked in sales at a publishing house, and his bag was always full of book catalogues. Whenever they became useless, he used the catalogue pages to paper the ceilings and walls of the attic. These pages often contained brief book summaries and author biographies, but they all stopped short of the parts I was most curious about. And that’s why I started reading books. Because I wanted to know how the stories turned out. I also discovered that most of them were about failure. Since I was a child raised on stories like these, I now write about the failures of a certain individual. A story depicts human failure, and this story will go on, as long as there is a reader who opens the book and is willing to find either despair or solace in the failure within the pages.

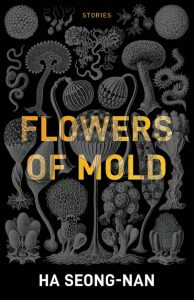

10. Your short story collection, Flowers of Mold, was recently translated into English by Janet Hong, 20 years after it was published in Korea. The collection feels extremely contemporary, but do you feel that the audience and impact of this book has shifted in the two decades since it was released? Do you worry that English-speaking audiences won’t fully grasp the context of the stories?

10. Your short story collection, Flowers of Mold, was recently translated into English by Janet Hong, 20 years after it was published in Korea. The collection feels extremely contemporary, but do you feel that the audience and impact of this book has shifted in the two decades since it was released? Do you worry that English-speaking audiences won’t fully grasp the context of the stories?

재닛 홍 번역의 은 20년 전 한국에서 라는 제목으로 출판되었다. 한국의 출판사 편집자들은 트렌드에 민감하고 독자들의 흥미를 끌어당길 제목을 궁리하다가 이것으로 결정했을 것이다. ‘옆집 여자’라는 소설의 제목은 뭔가 비밀스러움을 가진 옆집 여자를 성적 대상화한 것이 아닌가 하는 의심 속에서 ‘앞집 여자’라는 조금 바뀐 제목의 드라마까지 나오게 되었다. 물론 소설과는 전혀 상관없는 내용이었다.

당장 지금 한국의 젊은 독자들은 ‘옆집 여자’라는 소설의 제목부터 난색을 표할지 모르겠다. 문장은 또 어떤가. 그 당시의 유행을 따르고 있어서 지금의 독자들이 따라 읽기에는 부담스러운, 어쩌면 뽕이 잔뜩 들어간 유행 지난 정장처럼 느껴질지도 모르겠다. 여성을 소비하고 있다는 비난을 피할 수 없을지도 모르고 여자의 적은 여자라는 진부하고 의심스러운 문제를 꺼냈다고 공격을 받을지도 모른다. 의 경우 남이 버린 쓰레기봉투를 뒤지는 것은 개인정보유출로 법에 저촉되는 일이 되었다. 그러나 한국의 여성들에게 출산과 육아, 그로 인한 경력 단절은 여전한 문제이다. 다른 나라의 사정도 크게 다르지 않을 테고, 소설 속 약자를 향한 시선을 누군가 알아채준다면, 재닛 홍의 감각적인 번역으로 다른 약점들을 가려졌을지도 모르겠다.

The collection Flowers of Mold, translated by Janet Hong, was originally published 20 years ago in Korea under the title The Woman Next Door. I’m sure the editors went with this title after gauging publishing trends and what seemed most appealing to readers at the time, but the title calls to mind a seductive woman with a secret, an object of male fantasy. Even a television series with a slightly different title of The Woman Across the Street appeared shortly after. Of course, it had nothing to do with the book.

These days, young Korean readers may disapprove of this title. Then what about the actual writing within the pages? Since it was written in the style of the times 20 years ago, the writing may seem contrived or overdone for current readers’ tastes, like an outdated suit with too much padding in the shoulders. I might even be accused of exploiting women, or come under attack for seeming to pit women against each other. In the case of Flowers of Mold, digging through other people’s garbage would now be a serious privacy breach. Despite the many changes we’ve seen in the last 20 years, the matters of childbirth, childcare, and career interruptions still remain huge problems for women in Korea. The situation in other countries is probably not all that much different. But if, in your generosity, you noted my attempt to give voice to those who are vulnerable and disenfranchised, I’d like to propose that Janet Hong’s perceptive translation has masked the book’s other shortcomings.

Ha Seong-nan was born in Seoul in 1967 and made her literary debut in 1996, after her graduation from the Seoul Institute of the Arts. Ha is the author of five short story collections and three novels. Over her career, she’s received a number of prestigious awards, such as the Dong-in Literary Award in 1999, Hankook Ilbo Literary Prize in 2000, the Isu Literature Prize in 2004, the Oh Yeong-su Literary Award in 2008, and the Contemporary Literature (Hyundae Munhak) Award in 2009.

Janet Hong is a writer and translator based in Vancouver, Canada. She won the TA First Translation Prize and the 16th LTI Korea Translation Award for her translation of Han Yujoo’s The Impossible Fairy Tale, which was a finalist for both the PEN Translation Prize and the National Translation Award, and longlisted for the 2019 International Dublin Literary Award. She has translated Ha Seong-nan’s Flowers of Mold, Ancco’s Bad Friends, and Keum Suk Gendry-Kim’s Grass.