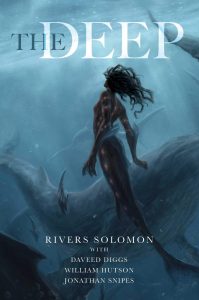

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, PEN America’s Lily Philpott speaks with Rivers Solomon, author of An Unkindness of Ghosts (Akashic Books, 2017) and The Deep (Saga Press, 2019).

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

Lou Astin’s The Little Me and the Great Me, a picture book originally published in 1957. My father had a copy that he read me often and referred to when he thought I wasn’t being my best self. I would never do that to a child—tell them they’re not being their best self when they’re angry, upset, sad, or vulnerable—but I must admit I still think about that book whenever I’m feeling mean-spirited, disdainful, or defensive, whenever I’m lashing out at those who don’t deserve it because sometimes we do that to make ourselves feel big when we are feeling small. I try to be gentle with my loved ones, I try to be the great me whenever I can. It’s a tension I’m still navigating as an adult, a little me and a great me, and one my characters are often navigating as well. We all fall a bit short, don’t we?

2. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

If I have a creative process, it’s haphazard and not one I’d necessarily recommend. Perhaps the best way to describe how I create would be anti-process, in fact. Anti-work. I do not appreciate habits or routines. Such apparatuses work for a short period, but inevitably, after a time, I come to see schedules and regimens as dictates, authoritarians—things as an anarchist I cannot abide.

I write, I get tired, I stop. I drop an idea. Sometimes I pick it up again. Sometimes I don’t. I write at night, when I feel like it. I write in the morning. I write not at all. I type frenzied notes on my phone that I’ll never return to. I mull things in the back of my mind while I binge TV. I spend months planning projects that I will lose interest in and never return to. That’s fine.

It’s not disciplined, and I’m glad for it. I’ve had to spend years unlearning what I’d been taught in school about what learning, growing, and process look like because the tools that are instilled in that environment are based on a capitalist mode of productivity that often seeks to squeeze the student (worker) dry. I’m relieved that compared to many, I was “successful” in school—meaning I got good grades and was often rewarded by the system—but very little that I learned helped me as a person or writer. When I became an adult, I didn’t know how to do something that I actually loved because in school that’s not the brief, is it?

My ineffective perfectionism, my self-loathing, my perceived “laziness” (exhaustion and fatigue, autistic burnout, overwhelm), all things picked up in school, have hindered my writing. By letting go of doing things the way they’re supposed to be done, the way I was taught to do them (efficiently, productively, forcibly), I’ve been able to write more than ever.

“I write, I get tired, I stop. I drop an idea. Sometimes I pick it up again. Sometimes I don’t. I write at night, when I feel like it. I write in the morning. I write not at all.”

3. How can writers affect resistance movements?

I’m not sure they can. Writers have influence, certainly, just like anyone does who speaks, but as far as sparking revolution? Each of us are bit players in a massive system, and even those books that enter the cultural zeitgeist, I hesitate to quantify the role they play in movements.

I write to please my readers. I write to entertain them and move them. I hope that at least on an individual scale, my work can be a balm to those suffering, as many works of writing have been to me. I hope that it might make one person survive that much longer by finding a kindred.

So I suppose that is a kind of resistance. Our survival.

4. What is your favorite bookstore or library?

Bluestockings in New York. It was a frequent haunt of mine as a teen, and I miss it.

5. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

Circe by Madeline Miller. I really loved it, and it made me want to write something as sweeping, epic, but deeply personal as it. I’m currently reading non-fiction, mostly research on Medieval culture and history. As far as fiction, I have a lot on my list, but I’m looking for some historical horror perhaps in the ballpark of Alma Katsu’s The Hunger.

“If I’m not feeling vulnerable, a little embarrassed, and deeply worried about how people will respond, then what I’ve written is probably not something that’s true to my experiences.”

6. What do you consider to be the biggest threat to free expression today? Have there been times when your right to free expression has been challenged?

School libraries, sadly. I’m very disturbed by the frequency with which they silently ban LGBT fiction for young readers, often in the places where such works are needed the most.

Publishers themselves, who often default to buying books they think will sell, effectively censoring marginalized voices.

If my work is being censored, I don’t know about it. I’ve felt very blessed at the reach my writing has gotten, especially with my first book coming from an independent press. We are living in a time where words can move really fast, and people who are searching can often find what they’re looking for—algorithms be damned.

7. What is the most daring thing you’ve ever put into words? Have you ever written something you wish you could take back?

I try to be daring with every piece I write. If I’m not feeling vulnerable, a little embarrassed, and deeply worried about how people will respond, then what I’ve written is probably not something that’s true to my experiences.

By the time any book comes out, a writer has generally evolved past who they were when they wrote it. I’d hope so, anyway! We’re always learning, growing, and changing. So there are regrets in the sense of, “Ah, I don’t exactly think that way anymore.” But that’s fine. I don’t mind having a record of who I’ve been. No one is perfect, and I like to think I can take criticism.

The Deep is a very scary project for me. It’s my second book, which means I have expectations to live up to. It’s much more experimental than my first book. It’s honoring a legacy of art that already exists. The narrative features complicated bodies, complicated genders, complicated emotions, complicated relationships. I’m dealing with genocide and climate change. It’s a lot, and a lot to live up to.

8. What advice do you have for young writers?

8. What advice do you have for young writers?

You’re not a failure if you can’t mold yourself into the arbitrary form you need to be in order to thrive inside the capitalist colossus. The world has failed you, not the reverse. Be bitter. Fight. Cherish your friends. Write but only if you are moved to do so. Play the game sometimes if it pays the bills! Or don’t! Rebel against a publishing industry that sorts voices into tiers, that pays inequitably, that still prioritizes whiteness. Support micropresses. Donate money when you’ve got it and ask for it when you need it. I’d be dead if I didn’t ask for money from strangers on the internet.

I also hope, as much as it is possible for you, if you decide to do an MFA, you do one that is fully funded. I know for myriad reasons this is not available to everyone, and of course I cannot claim it is never worth it to pay for graduate studies. But I will say I applied for a PhD here in the UK at a school I dreamed of attending with a rockstar creative writing staff and a supervisor who I low-key had a crush on, but turned it down because I did not receive funding. Debt is an unbelievable weight and it’s one that’s particularly used to keep the marginalized beholden to a system that kills us.

But also, ignore that advice if it doesn’t speak to your heart. I am but one person with one set of experiences.

9. Which writers working today are you most excited by?

Jamie Berrout, especially her non-fiction/essays critiquing publishing. Support the Trans Women Writers Collective on Patreon to see the booklet series she publishes featuring poetry, fiction, and non-fiction by exclusively trans women writers. I especially loved Legalize Crime and Against Revolution, two zines by the writer Winter. The covers for the series are also all stunning and I believe largely designed by Berrout herself.

I love R.B Lemberg, whose novella The Four Profound Weaves is forthcoming from Tachyon in 2020. Lyrical and unflinching.

Some other writers I’m processing, enjoying, learning from: Kai Cheng Thom, Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, Casey Plett.

10. Which writer, living or dead, would you most like to meet? What would you like to discuss?

Nella Larsen. I really need to know if the queer-coding in her novels was intentional, and I want her to know that her work is so subtle and so appreciated and that Quicksand did a lot of what Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man did in a way that spoke directly to Black womanhood.

Rivers Solomon is the author of An Unkindness of Ghosts, and is a finalist for the John W. Campbell Award finalist for Best New Writer. They graduated from Stanford University with a degree in comparative studies in race and ethnicity and hold an MFA in fiction writing from the Michener Center for Writers. Though originally from the United States, they currently live in Cambridge, England, with their family. The Deep is their second book. Find them on Twitter @cyborgyndroid.