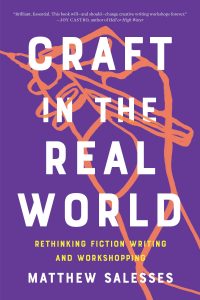

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Jared Jackson speaks with Matthew Salesses, author of Craft in the Real World: Rethinking Fiction Writing and Workshopping (Catapult, 2021).

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

I’m not sure. Goodnight Moon? The page that says, “Goodnight, nobody.”

2. What did your creative process look like for your most recent book, Craft in the Real World: Rethinking Fiction Writing and Workshopping, which includes writing exercises, suggestions for building syllabi, and guidance for reading creative work? How did you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

I wrote a lot of the book as essays and blog posts for various magazines, especially Pleiades. It’s all stuff I have thought about, taught, and lived.

“A person’s identity and writing are negotiations with culture and power. Workshop is often an intense microcosm of this relationship.”

3. What is one book or piece of writing you return to as a teacher? Why?

I have taught The Woman Warrior many times now, and I continue teaching it because it always teaches me and can lead a class anywhere.

4. What was one of the most surprising things you learned in writing your book?

The CIA funding the Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

5. Your book examines how to rethink craft—and the teaching of it—to better serve writers with diverse backgrounds. How does your identity shape your writing? How was your workshop experience affected by a limited, centered identity different than your own?

A person’s identity and writing are negotiations with culture and power. Workshop is often an intense microcosm of this relationship.

“What we think of as ‘normal’ or ‘right’ in storytelling has consequences on who we think of as ‘normal’ or ‘right’ in real life. . . I wonder about how often I have heard that the protagonist of a story is the person who has the most agency—in real life, who has the most agency usually comes down to who has the most privilege. Stories teach us how to be in the world, and from a young age, we learn that the kind of person who gets to be the protagonist is the kind of person who has the most power in the world.”

6. What advice do you have for teachers of young writers?

Writing can be about joy, not just about surviving—and often resurviving, via criticism—trauma.

7. Why do you think people need stories?

To be human.

8. The opening section of the book questions the existence of “pure craft.” What is craft? Why is the way we tell stories important, and what are the potential consequences?

8. The opening section of the book questions the existence of “pure craft.” What is craft? Why is the way we tell stories important, and what are the potential consequences?

The book argues that craft is a set of cultural expectations. The example I give in that chapter is how writers often tell students to use the dialogue tags “say” and “ask” in most cases because those tags are “invisible”—they don’t call attention to themselves. The reason these tags don’t call attention to themselves is that we have read them a lot. They’re “invisible” because of our experience as readers within a certain tradition. If most of what we read used the terms “state” and “question,” then those tags would be more invisible. The same principle applies to a three-act structure or an Aristotelian plot or whether to name a character’s race or not. And of course, what we think of as “normal” or “right” in storytelling has consequences on who we think of as “normal” or “right” in real life.

One thing I wonder about is how often I have heard that the protagonist of a story is the person who has the most agency—in real life, who has the most agency usually comes down to who has the most privilege. Stories teach us how to be in the world, and from a young age, we learn that the kind of person who gets to be the protagonist is the kind of person who has the most power in the world. This is just one example.

9. What are the limitations of the “traditional” writing workshop? What would happen if we expanded our ideas? Where should we start?

I started with what Nami Mun said to me once at an AWP Conference, that each workshop she runs is different because each student/story is different. This feels like a good place to start.

10. In 2020, we witnessed the publishing community reckon with diversity—from #PublishingPaidMe to hiring and structural changes. What made you want to interrogate, as your book describes, “the core of published fiction: how we teach and write it?” What are your hopes for the future?

I have seen this reckoning before. My hope is for not a reckoning, but a remaking.

Matthew Salesses is the author of three novels, Disappear Doppelgänger Disappear, The Hundred-Year Flood, and I’m Not Saying, I’m Just Saying. He was adopted from Korea and currently lives in Iowa.