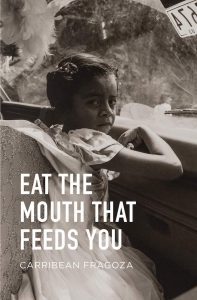

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Viviane Eng speaks with Carribean Fragoza, author of Eat the Mouth That Feeds You (City Lights, 2021).

1. What was an early experience where you learned that language had power?

1. What was an early experience where you learned that language had power?

As a child, I often got in trouble for saying what I thought out loud, even if it was true. Especially if it was true. So I understood pretty early on that there was some strange and troublesome power to language and that I had a particular knack for it. My mother would scold me and say, “You have to think before you speak!” When I learned to write, I learned to yield that power of language with more care.

It was a way to think before speaking, though probably not in the way my mom had intended. I learned that if you think carefully enough, you can whittle your words into a very sharp point, which could be useful in various scenarios. And writing, conversely, could also help create space. As a young person living in a quite cramped home, I always yearned for more space for my ideas and projects. I used to want to be an artist and was pretty committed to making things until I ran out of space and didn’t have enough money for materials. Writing allowed me to continue exploring, creating worlds, and connecting with others, with very little.

2. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

I think about this a lot. Fiction is very real to me, not just because my characters and settings are often inspired by real people, places, and events, but because they also address emotions and ideas that are real. I think people who don’t understand fiction negatively associate it with untruth or even lies. While this has been true in some cases, overall, I think that fiction can get us closer to emotional and ideological truths that are difficult to approach in nonfiction.

I also write a lot of nonfiction, so I often make decisions about what absolutely should be true to fact and what can also venture into other territory. But as a rule, nonfiction should be factual, and to be clear, I am always opposed to art—including fiction—being used as vehicles or instruments for lies.

“Fiction is very real to me, not just because my characters and settings are often inspired by real people, places, and events, but because they also address emotions and ideas that are real. I think people who don’t understand fiction negatively associate it with untruth or even lies. While this has been true in some cases, overall, I think that fiction can get us closer to emotional and ideological truths that are difficult to approach in nonfiction.”

3. Myriam Gurba described your stories as a “Chicanx gothic” because, in your own words, “there’s this constant looming of darkness and oppression” present in much of your work. What do you think are the elements of a Chicanx gothic form? What makes the gothic genre especially fitting in talking about immigrant experiences?

I think that in my work and in my outlook in general, I always try to hold the darkness and tragedy of life together with light and vitality. It’s also an integral part of Mexican culture to hold two oppositional forces at the same time—life and death. Our ancestors understood this and embraced death as an integral part of their philosophical and cosmological views.

I can also never ignore how colonization and the various oppressions it has propagated continue to shape our lives in so many crucial ways. Racism, capitalism, and patriarchy are all part of our lives at very micro and macro levels. At the same time, these don’t define everything. We, colonized peoples, have our joy and creativity, and this makes all the difference.

I don’t know exactly what Chicanx gothic is, but I do believe that as a genre, it’s something that is being invented and shaped and evolved as more Latinx and Chicanx writers engage publicly in literary conversations. It’s very exciting to imagine what we’ll come up with that will be relevant and resonant with our lived experiences. When I think of Chicanx gothic, I don’t immediately think of a literary genre. I think of a Chicana wearing a lot eyeliner listening to Siouxsie and the Banshees and The Cure somewhere in Southeast Los Angeles or in the San Gabriel Valley.

Kids growing up in industrial neighborhoods on the margins of Los Angeles have plenty of gloom and doom. Maybe we don’t have gothic churches and rainy days as they do in Europe, but we do have skies clouded with air pollution spewing out of factories, and tons of grey concrete and asphalt everywhere. We have plenty to be moody about, but we also like to party. I think that makes a good combo for good art-making, including literature.

“In my work and in my outlook in general, I always try to hold the darkness and tragedy of life together with light and vitality. It’s also an integral part of Mexican culture to hold two oppositional forces at the same time—life and death. Our ancestors understood this and embraced death as an integral part of their philosophical and cosmological views.”

4. What is a moment of frustration that you’ve encountered in the writing process, and how did you overcome it?

Nearly every piece of writing I’ve ever attempted has always been accompanied with some amount of frustration. Right off the bat, there’s the frustration of not being able to get to your writing at all when you’re working jobs or taking care of the kids. And even then, writing is always hard for me because every time I sit down to write something, it feels like I’m learning to write for the first time, like I’ve forgotten all my tricks. This is in part because I want to approach writing with new eyes every time, and perhaps learn or try something new instead of just sticking to a formula. But some formulas at their most basic can be helpful, especially when writing nonfiction.

In fiction, however, the territory is so wide open that I don’t have a formula (yet) to fall back on. And when I’m extremely stuck in writing, I have found that it’s usually because though the story is ready to be told—and it wants to be told by me—I am not ready to tell it yet. Usually it means that I need to learn more and read more—I need more tools or more time to figure it out. Sometimes it takes a weekend. Sometimes it takes years. It’s been my experience that my intuition is usually correct in recognizing the story, whether it’s through a character’s voice, an image, or an emotion, but later I’ll see that I was missing certain tools to build it into something. Sometimes the tools don’t exist, and you have to make them up.

I recently read an interview with Viet Thanh Nguyen where he talks about how he figured out a way to write criticism in his fiction by unlearning a lot of things he’d been taught about literature and what it could or could not do. As we get more writers like Nguyen, particularly writers of color with new visions and ambitions, we’ll be getting a whole new set of tools that will make new kinds of stories possible. Hopefully, our American literary canon is on its way to looking very different and will continue to transform as more of us write and publish our stories.

5. What is your relationship to place and story? Are there specific places you keep going back to in your writing?

Place and story are always intimately connected in nearly all of my writing. Even when the place is not the centerpiece, it’s never a neutral or interchangeable backdrop. I really believe that places where we live can play an enormous role in shaping us. I believe that while people belong to themselves, many of us also belong to a community, a neighborhood, a town, or a city. We belong to place. And place itself can also be a strong actor with its own motives that are as powerful, if not more, than the characters themselves.

“Place and story are always intimately connected in nearly all of my writing. . . I really believe that places where we live can play an enormous role in shaping us. I believe that while people belong to themselves, many of us also belong to a community, a neighborhood, a town, or a city. We belong to place. And place itself can also be a strong actor with its own motives that are as powerful, if not more, than the characters themselves.”

In addition, every place is full of stories of its own. Every place is ancient and sedimented with past lives that can find their own ways to speak to us. I often write stories that take place in working-class suburbs comprised predominantly of people of color that have worked hard to carve into a home. These suburbs, of course, don’t look like the suburbs portrayed in popular culture or in the media.

Having grown up in South El Monte, a suburb of the San Gabriel Valley on the east side of Los Angeles County, it’s been very important for me to subvert ideas about who people of color are and where we live. We live in cities, we live in suburbs, and we live in rural areas too. We’re part of the social and geographic fabric of this country all across the board.

6. What advice do you have for young writers, especially writers who are children of immigrants, like yourself?

My advice to the children of immigrants is to listen carefully and fully to the stories and voices that are around them. The very small and the very big, the very young, and the very old. The loud and the quiet, perhaps especially the quiet ones. Listen critically, too, of course, but first listen to receive the stories. We often learn to listen to the most dominant voices, especially in American culture that is so English language-dominated, male-centric, heteronormative, action-driven, and violence-obsessed.

Thankfully, there are other ways to write and to tell stories. As the children of immigrants, we also have the advantage of being more closely connected to entire bodies of international literature that Americans often foolishly ignore. I would recommend that, if possible, they delve into and relish that expansive space of possibility offered by those generations of writers.

“My advice to the children of immigrants is to listen carefully and fully to the stories and voices that are around them. The very small and the very big, the very young, and the very old. The loud and the quiet, perhaps especially the quiet ones. Listen critically, too, of course, but first listen to receive the stories.”

7. What’s a piece of art (literary or not) that moves you and mobilizes your work?

Stylistically, the bold theatricality of all of Juan Rulfo’s writings and José Clemente Orozco’s paintings and murals, particularly El Hombre en Llamas, animate my emotional and aesthetic sensibility. They are both from Jalisco, which is where my family is from, and their work speaks to me in ways that feel very natural. They are sort of raw, wry, and sometimes brutal but in very nuanced, sophisticated ways.

The child-centered but very adult writings of Ana María Matute influenced me since I was a young writer. I’m also inspired or informed by the songs of José Alfredo Jiménez, specifically “Cielo Rojo” and “Un Mundo Raro,” particularly when they are interpreted by women such as Lola Beltrán, Chavela Vargas, and Lila Downs.

The honesty, rage, and unapologetic desire in the voices of Jamaica Kincaid’s protagonists are very important to me, as well as the musicality and pointed humor of Grace Paley. The interiority of William Gass’s In the Heart of the Heart of the Country was a revelation because it instructed me to delve into new depths of character voice.

8. What has been your experience of preparing to release a new book during a global pandemic?

8. What has been your experience of preparing to release a new book during a global pandemic?

My publishing date was pushed back twice from October 2020, to March 23, 2021, and more recently, to March 31. The pandemic made us rethink our pub date, and the more recent freeze in Texas delayed our shipments, so we pushed back a little more. Earlier in February 2020, I published a book of essays (East of East: The Making of Greater El Monte) that I edited with my husband Romeo Guzman and our coeditors Alex Sayf Cummings and Ryan Reft.

Shortly after our pub date, the pandemic shut everything down and all of our events were cancelled. And yet, over a year later, our book has continued to chug along and circulate into all of the hands we wanted to have it, and more! Everything about Eat the Mouth That Feeds You has also been a very long process. I had been writing it for over a decade before I even knew it was a book. Even after that, it still was a long process. I’m okay with that. I have a lot of things that I juggle, and I always need more time to do them.

Everything I do, I believe in intensely and feel that they are all worth waiting for. This pandemic has challenged and taught many of us to exercise our patience as if it were an underworked, flabby muscle because we have all become so accustomed to instant gratification and quick response. Patience can be painful if you are out of practice.

9. Where was your favorite place to read as a child?

I read constantly, everywhere. My mom was very permissive about letting me read whenever I wanted instead of making me do endless chores. This is very significant because she grew up in a household where only the men were permitted to be studious and the women were required to sustain the home. And yet, she let me read.

But I have very specific memories of reading in a walk-in closet. Our house is a small two-bedroom bungalow for five people, and if I wanted to read late at night after everyone had gone to bed, I’d have to read in the closet so I wouldn’t disturb anyone with the light. It was a cozy space with enough room to curl up into all the stuff we stored there.

10. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

The last book I read was Eula Biss’s Having and Being Had and Ben Ehrenreich’s Desert Notebooks. I’ve been reading a lot of nonfiction. Next up are Randa Jarrar’s Love Is an Ex-Country, Yxta Maya Murray’s Art is Everything, and for inspiration—I feel a new story coming—I’m reading Silvia Federici’s Caliban and the Witch.

The daughter of Mexican immigrants, Carribean Fragoza was raised in South El Monte, CA. After graduating from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), Fragoza completed the Creative Writing MFA program at the CalArts School of Critical Studies, where she worked with writers Douglas Kearney and Norman Klein. Fragoza is founder of Vicious Ladies, coeditor of the University of California Press’s acclaimed California cultural journal, Boom California, and founder of the South El Monte Arts Posse, an interdisciplinary arts collective.

Her fiction and nonfiction have appeared in numerous publications, including BOMB, Huizache, and the Los Angeles Review of Books. She is the coeditor of East of East: The Making of Greater El Monte, published in February 2020 by Rutgers University Press and Romeo Guzmán, senior writer at Tropics of Meta. Fragoza is the coordinator of the Kingsley and Kate Tufts Poetry Awards at Claremont Graduate University, and she lives in the San Gabriel Valley in Los Angeles County.