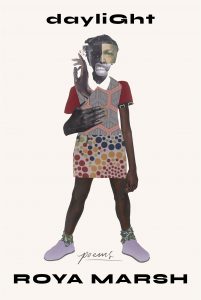

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Jared Jackson speaks with Roya Marsh, author of dayliGht (MCD x FSG Originals, 2020).

1. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

I write through a commitment to truth, which was born of a yearning to be heard. I come from a culture of sweeping things under the rug to save face, and I realize now that for so long, we were hiding from the white gaze. The truth is, we do have to teach our children how to make it home safely. Much of what we are taught about how to survive in the world is a response to historical trauma. And having the gift of manipulating language in such a way that I can bend the dark into light, is what has allowed my healing to begin. Writing poetry was the first time I was able to say some things out loud, and it ultimately brought me to therapy.

The line between truth and fiction can be thin. Our lives are made up of the choices we make, and at times, the choices made by those around us. There are always elements of truth in fiction, yet fiction allows you to discover truths that maybe haven’t existed for you. With poetry, particularly performance poetry, people sometimes question your truth, or require evidence of your truth in order to give weight or validity to your work. Today, audiences want access, a window into your inspiration, an answer to how you crafted this or that piece, but the answers they’re looking for are always in the writing.

2. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

My creative process varies from project to project. I try to hold myself to a minimum of 40 silent minutes of writing a day. I would love to dedicate more time (and sometimes I do), but if I am not working on a specific project, that 40-minute minimum keeps me grounded and alleviates any feelings of laziness or neglect of my craft.

Luckily, I am inspired by so many things and am often moved to writing as a way of processing. Facilitating workshops and witnessing different groups navigate lessons and prompts really keeps my candle burning. Young people have some of the most brilliant minds in this world, and having them blow open a prompt allows me the space to further explore my own writing choices.

“Having the gift of manipulating language in such a way that I can bend the dark into light, is what has allowed my healing to begin.”

3. What is one book or piece of writing you love that readers might not know about?

Jennifer Falú’s Love, Above All Things, is the most honest bit of writing that I have ever experienced. It’s a one woman show about the strength and resilience a Black woman must possess to survive. The show consists of a selection of poems, each of which can stand alone, each one powerful enough to leave you in awe of her talent. Falú uses history, rhythm, congas, dance, and other aspects of the African diaspora to power through a tale of losing love, losing children, and the journey to get it all back while keeping love above all things.

4. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

I just finished HULL by Xandria Phillips! It’s like a science fair during Black History Month, with all the quirks of a TV drama. In one poem, they write: “We’re not here to dismantle anything / we’ve come to burn the big house down,” calling out the sons of racism and patriarchy, past and present, with a nod to Audre Lorde. Phillips tells a tale of how we got here and what we plan to do now. The collection takes us on a journey through queerness and Blackness, experimenting with form while folding laundry with Sarah Baartman, or sharing an intimate cup of chamomile tea with Michelle Obama. These poems navigate beautifully—among other things—the risks we run for the chance to love who and what we want, and recall a childhood in which none of this was possible. HULL is full of magic, wonder, tragedy, lust, yearning, and loss!

Next, I’m going to sink into Even the Saints Audition by Raych Jackson.

5. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity?”

Academia and other professionally codified spaces have deemed my identity as a writer and much of the work that I value most deeply to be too raw or controversial. At times, my work has been called “too Black” (translation: “too much like me”). I’ve faced many challenges as a Black butch woman and have had to work overtime to remain visible. There is a sort of softening that is often proposed of my writing, attempts to make me and my work more palatable for those not ready to stomach my truth. The goal of these proposals is often simply to police my tone and my anger, and control the way my message is received. To that, I respond with a statement coined by the Black Poets Speak Out movement, “I am a Black poet who will not remain silent while this nation continues to murder Black people. I have a right to be angry.”

“People need an outlet for expression, regardless of what form that expression takes. Poetry is a vehicle for delivering truth and possibility. It allows room for the impossible to live.”

6. What advice do you have for young writers?

Read. Write. Write truthfully. Write freely. Write creatively. Invent worlds better than the one you’re living in. Let folks read it. Read it yourself. Live it. Be willing and available to learn. Be a listener. Tell the story the way you wish it to be told, and remain vigilant and uncompromised.

7. Which writers working today are you most excited by?

The youth are here to teach us all what the world needs. Imani Davis is a mastermind of their craft; and I am willing to sit at their table and read, learn, and write endlessly. I could go on forever, so I’ll rattle off just a few names here: Justin Phillip Reed, Terrance Hayes, Elizabeth Acevedo, Clint Smith III, Jon Sands, Adam Falkner, Arhm Choi Wild, Mahogany L. Browne, Jive Poetic, Lindsay Young, and Paul Tran.

8. Why do you think people need poetry?

I know that people need an outlet for expression, regardless of what form that expression takes. Poetry is a vehicle for delivering truth and possibility. It allows room for the impossible to live. It exposes readers to the different levels of breakability they possess. Awareness of our vulnerabilities gives us room for to connect, to see one another, to learn a new language that resides within the language we already use. Poets cut through the bullshit and manipulate language to give readers a more nuanced idea of living. Poetry is freeing.

“Representation lends a sense of belonging. It lessens the erasure we live through; it lets you know that you’re seen, that there are people like you, that your story is worthy of being told.”

9. There is a wave of spoken word and slam poets who have shifted to formalism and published collections to much acclaim. Does the writing process change, and if so, how? Does one form inform the other?

I’m a writer. It is most important to acknowledge that. I refuse to be pigeonholed or pegged as one thing or another. Spoken Word is such a broad term that the Grammy Award in this category most often goes to the bestselling audiobook and is seldom rewarded to a poet. For a time, I used slam competitions as a means of growing, expanding my pen game, and garnering recognition. But for me, the writing comes in waves, and the journey is figuring out new and improved ways to deliver my truth so that folks can feel liberated enough to reveal their own.

I never intended to be known as a slam poet—no shade to anyone who does aspire to that title—but it is definitely one of many titles I have assumed. My goal has always been to leave a lasting imprint on the literary world and see my message enter rooms and rest in hands and hearts that my voice might never otherwise reach.

10. In the author’s note to dayliGht you write, “I know representation isn’t a cure, but it’s a start.” How can representation liberate communities? Why is it important to have literature that reflects readers?

10. In the author’s note to dayliGht you write, “I know representation isn’t a cure, but it’s a start.” How can representation liberate communities? Why is it important to have literature that reflects readers?

It feels impossible to explain to someone who has always been represented, why being underrepresented is so detrimental to one’s physical, emotional, and spiritual development. I write for myself. But I also write for those of us who grew up identifying with the outsider characters—the grunge girls who wore sloppy pigtails and tennis shoes to dress down floral jumpers, the girls who identified with the Gross sisters on The Proud Family (even in a Black cartoon, our differences are deviant). Representation lends a sense of belonging. It lessens the erasure we live through; it lets you know that you’re seen, that there are people like you, that your story is worthy of being told. It is incredibly empowering to see someone who looks like you as a main character in a story, working and fighting. I write every day to show little girls—like the little girl I was—what it looks like to have the audacity to take control of your own life.

Roya Marsh, a Bronx native, is a poet, performer, educator, and activist. She is the poet in residence at Urban Word NYC, and she works feverishly toward LGBTQIA justice and dismantling white supremacy. Marsh’s work has been featured in The BreakBeat Poets Vol 2: Black Girl Magic (2018).