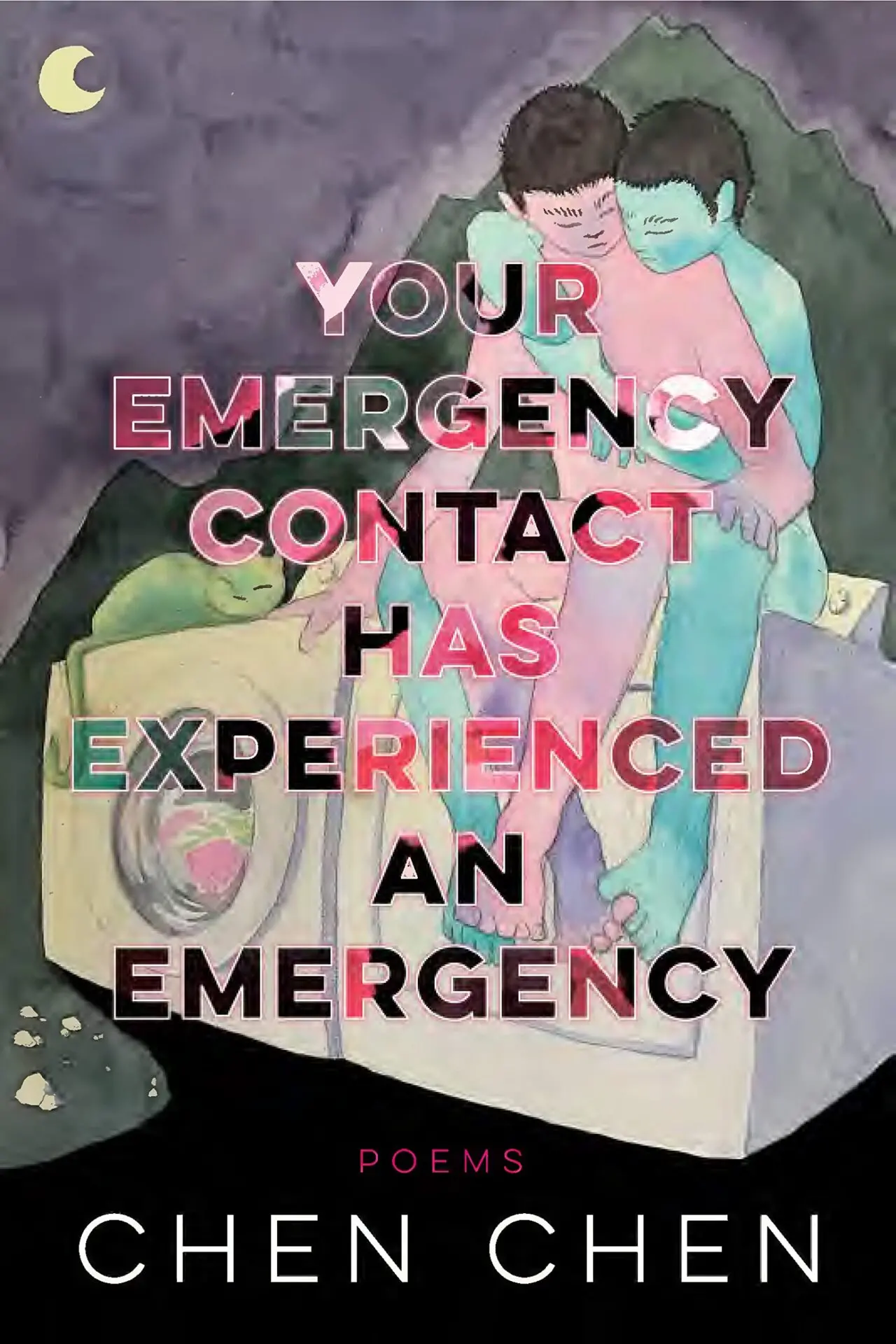

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, PEN America’s Author’s Evening Intern Ayla Schultz speaks with Chen Chen, author of Your Emergency Contact Has Experienced an Emergency (BOA Editions, 2022). Amazon, Bookshop.

1. Your first collection When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities was published in 2017. Have your poetic impulses changed since then? Do you think your poetic “thesis,” so to speak, has altered over the past few years? My poetic impulses and theses shift with each collection—and I think about them in terms of questions. The first book’s question was: “How can growing up extend beyond a static, linear, heteronormative notion of adulthood?” While this second book’s question is: “What happens when the institutions and the people we rely on in times of crisis are themselves undergoing fracture and upheaval?”

Though the questions are different, many of my obsessions in terms of subject matter overlap from book to book. I’m still wrestling with family, still thinking through race and immigration, continuing to explore and to celebrate the possibilities of queer love and friendship. It’s the framing that changes, and the formal choices—which allow me to revisit without treading the same exact ground (at least that’s what I’ve tried to do). And in writing these books, I’m not trying to find firm answers to my questions; rather, I’m interested in deepening the asking itself, to let it lead me to further surprise and provocation. As James Baldwin put it, “The purpose of art is to lay bare the questions that have been hidden by the answers.”

2. You often write about identity, giving a soaring voice to your experience of being a queer Asian man in America—in many ways your work has helped shape the identity of and offer necessary representation to many people. In turn, do you think your work has shaped your identity and how you look at the world? If yes, in what ways?

I’m so moved and grateful that my work has opened up a space for some readers in this way. It’s astonishing. I don’t intend to fully represent anyone but myself, but at the same time I understand that as a writer I’m responsible and accountable for the ways in which I depict and discuss identity on the page. So, actually, I experience my work first and foremost as shaping my own identity and how I look at the world—writing has long been my primary method for doing that. I often feel that I don’t know how I truly feel until I try writing it out. And that process might turn into a poem or it might take another literary form or just stay as a piece of journaling. All types of writing are valuable to me, whether they end up being something published or not.

I need writing to figure out what my experiences as a queer Asian man in America mean, what they could mean, what further experiences I want to have. My first book was largely a way for me to think about my (ecstatic yet also traumatic) childhood and my (traumatic yet also ecstatic) adolescence—and why I’ve come to seek the particular kinds of joy and love that I do, in adulthood. My second book resides more firmly in an adult realm, though at the same time it also refuses a distinct line between a “mature” perspective vs. a “childlike” imagination and sense of wonder. And this second book dives into what being a queer Asian teacher and, in some ways, community leader is like. My identity these days is very much informed by how I am called to show up for others, to mentor and nurture, while continuing to be mentored and nurtured myself in the midst of processing traumas both personal and collective.

“Poetry matters because it nourishes the heart. Maybe that sounds cheesy, but I don’t care. Art matters because it nourishes the heart. Like plums do. Like sunflowers. Like a good, long kiss in this brief, brief life.”

3. I have heard from many people that poetry is a “frivolous” and “incomprehensible” artform—one which does not fit into the American, highly capital-oriented idea of what a profession “should” look like. Has this discussion ever arisen amongst your students/peers/family and what do you say to them? As a follow up to that, do you think art is necessary for society?

As I get older, I have less and less patience for the idea that poetry and art don’t matter. Or maybe I always had little patience and, as I get older, am less capable of pretending! In any case, poetry and really all forms of art have saved my life—when I was a child not understanding why my immigrant parents seemed so sad; when I was teenager and started to understand and was deeply sad myself; when I was a lonely teenager not understanding why I wanted to be with other boys/why they didn’t want to be with me; when, as an adult, there’s still so much I don’t understand and what I do understand so often saddens me.

My parents still pressure me to get a “real job” because they don’t understand how I’m working all the time, in a place called imagination, in an office called heart. Though I don’t want to justify what I do and what I love by always talking about it in terms of labor. Poetry matters because it nourishes the heart. Maybe that sounds cheesy, but I don’t care. Art matters because it nourishes the heart. Like plums do. Like sunflowers. Like a good, long kiss in this brief, brief life.

4. You relish in playing with form through this collection—moving into a fascinating multi-part series in section two of your book, which you entitled “The Small Book of Questions” (after the brilliant collection published by Bhanu Kapil). What attracted you to that form, and those specific questions in particular?

I love Kapil’s work and I return in particular to The Vertical Interrogation of Strangers all the time. The twelve questions that structure that book are so generative. I was using them in my teaching and then realized that I wanted to write my own responses. I mean, “Who was responsible for the suffering of your mother?” feels like a question that I’ve already tried to engage with in my poems, so that one especially seemed a natural direction to go in, to continue going in. My sequence is much more narrative than what Kapil did in her work, a discovery which was illuminating—it showed me my tendencies, how I tend to travel through story, especially when given a longer form to navigate within.

In general, I think questions are a better place to start and to inhabit rather than super clear ideas. Fulfilling an idea can quickly become stifling; following a question opens thought and feeling up in unexpected ways. So, I’m always inviting my students to think about and talk about their questions. What are the questions fueling your quest as writers?

5. Many of your poems are dedicated to people, and after work by other poets. You also mention Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman multiple times through the collection—writers whom many consider the “parents” of American poetry. Are there any particular writers who hold spots in your poetic “family tree”? Any poets from whom you drew particular influence?

You didn’t ask this exactly, but I want to mention briefly why I reference Dickinson and Whitman to the degree I do. It’s because they’ve been such a presence in my literary life and imagination from a young age—Dickinson especially because my family lived in Amherst, Massachusetts for many years. Whitman, I think came later and I can’t remember if we really discussed his queerness in high school. And with Whitman I’ve come to recognize his problematic nationalism and imperialism, while still appreciating to some degree his sensuality and propulsive inventories.

Contemporary poets who are part of my family tree include teachers such as Aracelis Girmay, Martín Espada, Polina Barskova, and Michael Burkard. And there are so many other contemporary poets whose work matters deeply to me—Muriel Leung, Jennifer S. Cheng, and Michelle Lin are poets who show up in this new book. And Justin Chin, who died in 2015—I so wish I could’ve met him. Lines from his fantastic poem, “Lick My Butt” serve as one of the epigraphs for this new collection.

Some other poets in my family tree: Sam Herschel Wein, Mag Gabbert, Victoria Chang, Nikky Finney, Marina Tsvetaeva (author of this new collection’s other epigraph), Jean Valentine, Mary Ruefle, Ilya Kaminsky, Jericho Brown, Sarah Gambito, Joseph O. Legaspi, Federico García Lorca, and Tracy K. Smith. It was important to me in this new book to spell out some of my literary lineage because I wanted to be abundantly explicit with my gratitude and also because that was how I built and still often build my reading lists—looking to the poets I already love to point me in the direction of others I could love.

“I used to think I had to be completely fluent in Mandarin to use it in poems. But then I thought: well, I grew up in a multilingual household and used imperfect Mandarin alongside imperfect English all the time—why not write with the languages I actually speak?”

6. You have forged a gloriously, unabashedly, multilingual collection. What would you say to the American urge to translate and “explain” non-English words in literature? You talk frequently about the connection between language, literature, and colonialism—could you talk about how this idea plays into the fabric of this collection, and your philosophy of language as a whole?

I think of a great interview Cathy Linh Che did with The Rumpus in which she talks about her choice not to translate the Vietnamese in her poems. She says that she wants to write for someone who occupies her subject position. This was so liberating to me, as I used to think I had to be completely fluent in Mandarin to use it in poems. But then I thought: well, I grew up in a multilingual household and used imperfect Mandarin alongside imperfect English all the time—why not write with the languages I actually speak?

Che also mentions how her refugee parents had to look up words in order to survive in the US, so why shouldn’t a reader unfamiliar with Vietnamese make some effort, as well? I understand the risk of leaving some readers out… though actually I think they’re leaving themselves out by not doing some very basic work. And with Mandarin, with Chinese characters, these days it’s easier to look words up, especially if you have a smartphone. You can scan text or write out characters in an app. I did this exercise a couple times in an undergraduate poetry workshop at Brandeis, when we were reading Mary Jean Chan’s book Flèche—there’s one poem in particular that uses Chinese characters and I just gave the students the resources to look up the words. To me it’s less about a text being inherently “accessible” or not—it’s about pedagogy, it’s about tools, it’s about making a text more accessible by supporting readers in their learning process.

At the same time, I find there’s great value in some readers seeing how they aren’t the intended audience for every poem. It’s okay if you don’t understand or have difficulty understanding. It’s funny how there was also a bunch of French words in Flèche (including the title!) and yet that didn’t seem as much a hurdle as the Mandarin, when for a Mandarin speaker/reader, the French would of course be the hurdle. Since I was quite young, I was expected to understand Frost and Shakespeare and Dickinson, etc. I had to work at understanding their work. And now I’ve come to enjoy that level of engagement with a range of texts. But I want to remain humble with the knowledge that not every piece is made for me (while not using that as a cop-out for not attempting to engage!) and that if it’s really for someone else, that’s wonderful, too.

7. Do you think poetry has the power to help us reckon with our past, both globally and personally? Does it have the power to heal? You write a lot about your own childhood—do you think poetry has helped you reckon with your own past experiences?

I don’t think poetry alone can do any of these things, at least not fully. I think there’s a whole set of resources that’s needed to address traumatic pasts and to move toward healing. Therapeutic resources, medical resources, financial resources, social resources—entire systems need to be overhauled or altogether changed in order for more people to truly reckon with and heal from all kinds of harm and difficulty.

Poetry has certainly helped me reckon with my own past experiences—it’s a transformative act, to take those experiences and my memories and turn them into art. Still, if poetry were the only way I addressed issues, I would not be anywhere near okay. I need conversations, I need communities, I need funds, I need everyday pleasures, I need healthcare that includes mental health support, I need love and connection. It’s an amazing gift, that I’ve found many of these things through poetry, but again, poetry alone can’t sustain me or help me grow in all the vital ways.

8. How do you think other forms of art (music and visual arts for example) play into your work? Was there any particular piece which inspired you through your writing process?

I love so many forms of art and especially music, painting, and photography. Actually, I put together a soundtrack for this book. Though I just recently realized that Björk isn’t on this playlist—when she’s mentioned in a poem in the first section! Oh, and Alanis Morissette should be on here, too. Time for a revision/update.

Maybe I should also assemble a mood board of visual references. Ren Hang’s photography has been a big source of inspiration and he shows up in a poem in the last section. Such fresh, erotic, queer, playful, and always surprising portraits of Chinese youth in Hang’s oeuvre. I’d like to write more poetry in conversation with his work. I want to write in conversation with Wong Kar-wai’s films, as well, but that feels very daunting at the moment. Chungking Express and Happy Together (sort of on opposite ends of the emotional spectrum!) are all-time favorites. I love romance and Wong Kar-wai is so good at capturing both the swoon and the dysfunction of his characters’ wild love lives.

“If poetry were the only way I addressed issues, I would not be anywhere near okay. I need conversations, I need communities, I need funds, I need everyday pleasures, I need healthcare that includes mental health support, I need love and connection. It’s an amazing gift, that I’ve found many of these things through poetry, but again, poetry alone can’t sustain me or help me grow in all the vital ways.”

9. With the rise of book bans in the US, many of which being titles by BIPOC queer authors, are there any books you would recommend people (particularly younger people) read? As a teacher, how do you contextualize book bans in your own classrooms?

I recommend Ocean Vuong’s novel, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous. What a stunning book—the narrator’s voice is so vulnerable and psychologically precise. Honestly, I don’t think I’m the best person to ask for recommendations for younger people to read, as I haven’t kept up as much as I’d like to with literature specifically for the new generation. And I haven’t talked about book bans yet in class; I’ll have to think further about how I’d approach that.

Other books that come to mind for people more generally include Benjamin Garcia’s Thrown in the Throat, Rick Barot’s The Galleons, and Natalie Diaz’s Postcolonial Love Poem. I just taught Diaz’s “They Don’t Love You Like I Love You” in a poetry workshop and it was great to talk about how that poem draws on the Yeah Yeah Yeahs song “Maps” to examine racial dynamics in romantic as well as familial relationships.

10. Through my time writing I know I have accumulated a vast “cabbage patch”—a pile of work which for various reasons I could not finish. You talk about this in “Every Poem Is My Most Asian Poem” as well: “there’s the one that begins, Exquisitely / inquisitive, I wander with my well-moisturized elbows. / & ends, To aubergine or not to aubergine, that is / never the question. This great poem I will / never write.” Were there any other poems you wanted to or would have included in the collection? Do you have any piece which has been long-brewing and continues to steep?

I’ve got a chapbook called Explodingly Yours that’s coming out in January that’s basically b-sides from Your Emergency Contact plus a longer poem, “The School of Eternities,” which does appear in the full-length collection. This chapbook is a way for me to continue living in the world of this second book, while keeping the book from being far too long (it’s already somewhat lengthy for a poetry volume). These were poems I cut from the full-length but that I still like and think are strong enough to exist in a (smaller) collection. A couple might reappear in the next full-length, too. And these poems, all love/erotic poems in one way or another, give “The School of Eternities” a different context in which to sing.

As for the follow-up question, I really enjoy putting lines and images in poems just because I’ve been wanting to for a while—they’ve been sitting around in a notebook for months, sometimes years. I mean, originally, it was that I wanted a specific line or image to become its own full poem and I just couldn’t turn it into that and so am including it in something else. I just need that scrap of language to have a life in poetry. There are many, many scraps like this. One I keep thinking about has to do with airports and the physical as well as emotional spaces of arrivals and departures. Something like: “Arrival: rain. Departure: memory.”

Chen Chen is the author of two books of poetry, Your Emergency Contact Has Experienced an Emergency (BOA Editions, 2022) and When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities (BOA Editions, 2017), which was longlisted for the National Book Award and won the Thom Gunn Award, among other honors. His work appears in many publications, including Poetry and three editions of The Best American Poetry. He has received two Pushcart Prizes and fellowships from Kundiman, the National Endowment for the Arts, and United States Artists. He was the 2018-2022 Jacob Ziskind Poet-in-Residence at Brandeis University and currently teaches for the low-residency MFA programs at New England College and Stonecoast.