In 2017, authors Sarah and Ian Hoffman received a call from a journalist at The New York Times. The duo’s recent release, a picture book about a young boy who refuses to accept gender norms, had been banned in North Carolina, and the reporter wanted to interview the authors about it.

“We were like, ‘Oh my God, The New York Times is calling us? We’re going to have more sales, and people are going to know about our book. This is great,’” Sarah said. “It was almost fun.”

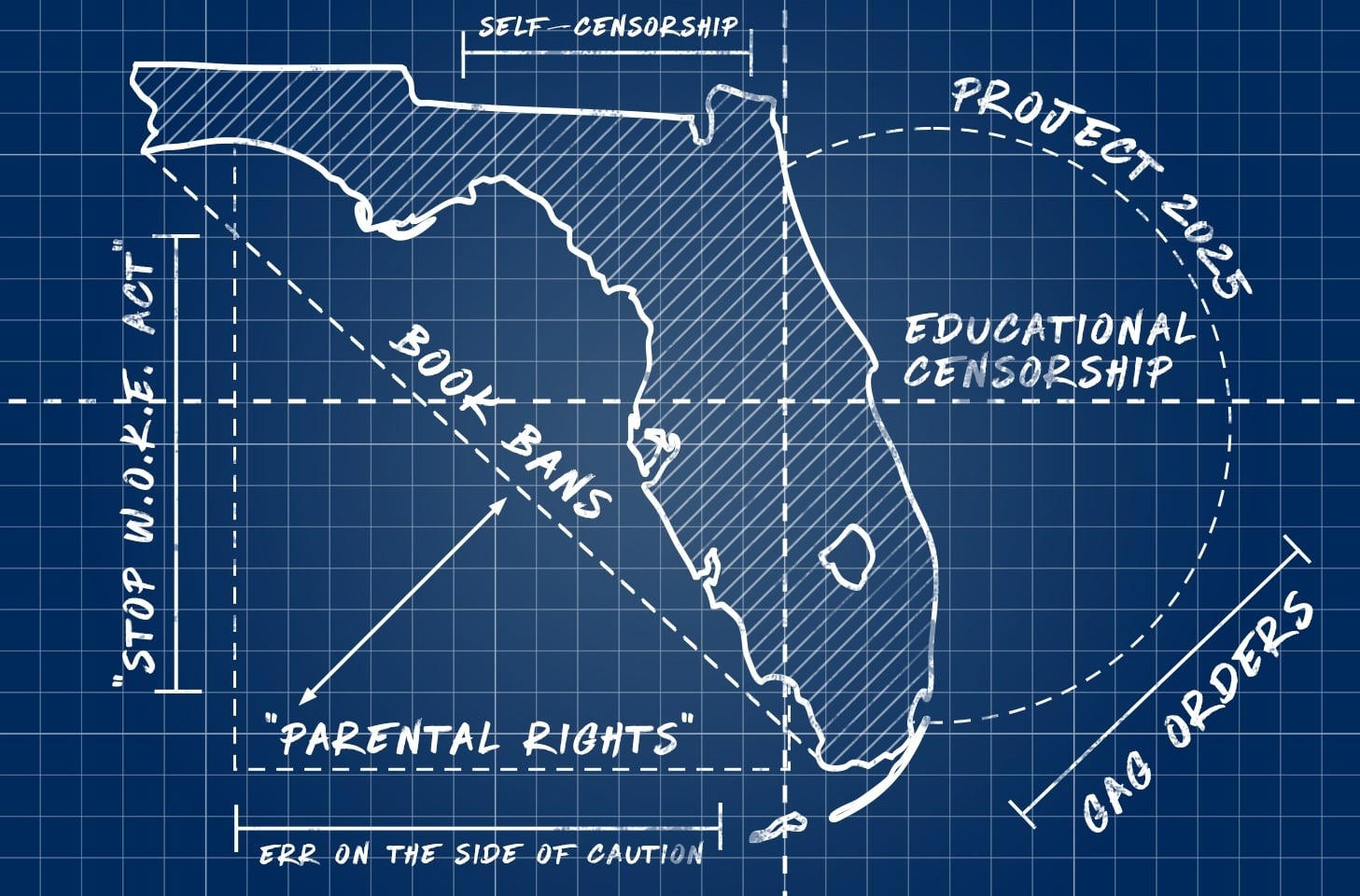

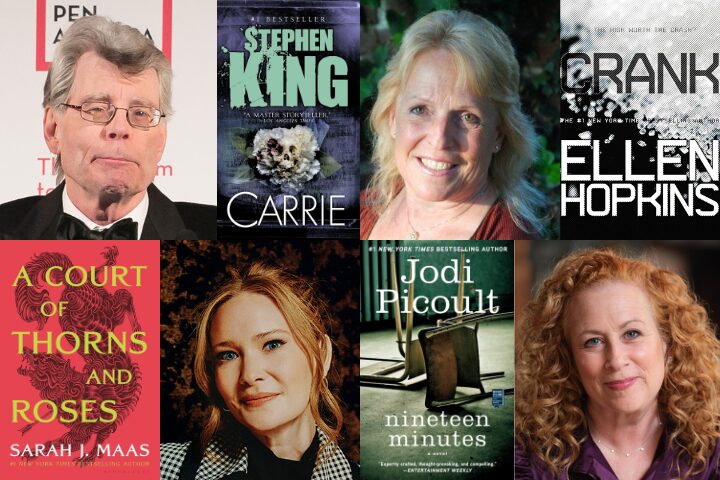

In the nine years since, nearly everything has changed. A single ban is rarely ever worth a story anymore; since 2021, PEN America has tracked nearly 23,000 instances of book bans. (In addition to Jacob’s New Dress, three of the Hoffmans’ later releases — Jacob’s School Play: Starring He, She, and They!, Jacob’s Room to Choose, and Jacob’s Missing Book — were targeted, and no Times coverage followed.)

As the bans have piled up, attitudes about them have shifted, too. Any hope that bans might bolster an author’s profile or sales has evaporated; now, authors know just the opposite to be true.

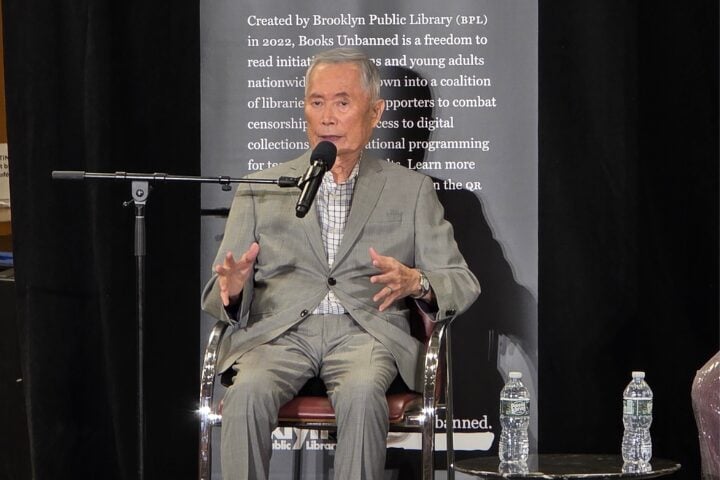

Recently, PEN America surveyed authors about the financial toll of literary censorship as part of its legal work challenging book bans. Many told us that although they can’t put a number on the harm bans cause, they know they’ve lost out on crucial sales and speaking engagements because of them.

Three schools canceled author Sarah Brannen’s visits after finding out she wrote Uncle Bobby’s Wedding, a picture book about a gay marriage. The children’s book was among those at the center of Mahmoud v. Taylor, a case in which the Supreme Court ruled that parents in a Maryland school district could opt their kids out of lessons featuring LGBTQ+ materials on religious grounds.

“I finally gave up trying to do school visits, which many authors rely on to make a living,” Brannen said. A BookRiot survey found that most children’s authors earn at least 25% of their annual income from school and library visits, and one in five earns a majority of their income from visits.

According to Maggie Tokuda-Hall, a founding member of Authors Against Book Bans and author of the banned books The Mermaid, the Witch, and the Sea and Squad, educators and librarians have pulled back from inviting authors with “even the mildest controversy” to speak with students at their schools. “But not only that, we are less likely to be invited to places like book festivals, or literary events, for fear of bringing that controversy with us,” she said.

Robin Stevenson, who has written over 30 books since 2007, said that she’s had to reckon with a sharp decline in speaking opportunities, especially school visits. But book bans and the climate of fear they’ve created have also had “a very significant impact” on the sales of her titles about LGBTQ+ characters, history, and activism.

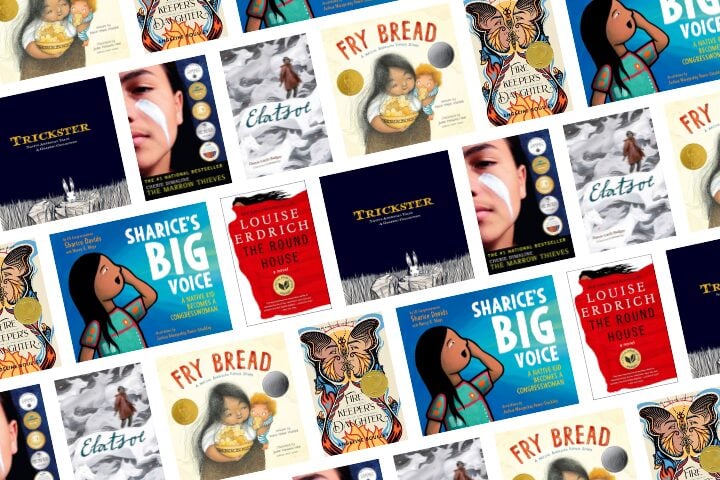

Author income can be erratic in the best of circumstances. Still, publishers including Penguin Random House have reported that sales of diverse books are down due to extended vetting and some schools’ unwillingness to buy books. Independent publisher Levine Querido, launched in 2020 and focused on publishing underrepresented voices, initially had strong sales for its diverse titles. By 2023, it reported sales were down 50%.

Kyle Lukoff, who has authored five banned titles including When Aidan Became a Brother, said he couldn’t speculate about what his career might have looked like had book bans not become so widespread — “but I do know that I should be invited to far more schools and communities than I currently am,” he said.

“Book banning is also connected to a larger suspicion of public education, the defunding of which also impacts my ability to earn a living,” Lukoff added.

The income that Andy Passchier earns as an illustrator has waned “from enough to survive to almost zero within the span of the year,” they said. Passchier illustrates books about identity and the LGBTQ+ community for kids, and though the rise of generative AI may have contributed to the decrease in their earnings, they pinpointed book bans as a likely factor too.

And censorship doesn’t only hurt a creator’s finances once their books are banned. Many of Charlotte Sullivan Wild’s projects have been subjected to publishing delays — sometimes for years — because they feature “controversial” topics.

“I’ve had editors say recently that they are not backing down. I know they don’t want to,” said Sullivan Wild, author of the banned picture book Love, Violet. “Yet the financial losses due to bans and soft censorship are, it appears to me at least, making it harder to sell books about certain identities. When those identities include your own, this can be beyond discouraging.”