“Save Our Mother Tongue”

Online Repression and Erasure of Mongolian Culture In China

Key Findings:

6.3 million Mongolian people have been stopped from using their own language.

Nearly 89% of known Mongolian cultural websites have been censored or banned.

Online communities have been restricted, including Bainuu, a Mongolian social media app with 400,000 internet users.

PEN America Experts:

Senior Manager, PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Center

Learn more about our partner, the Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center >>

Executive Summary

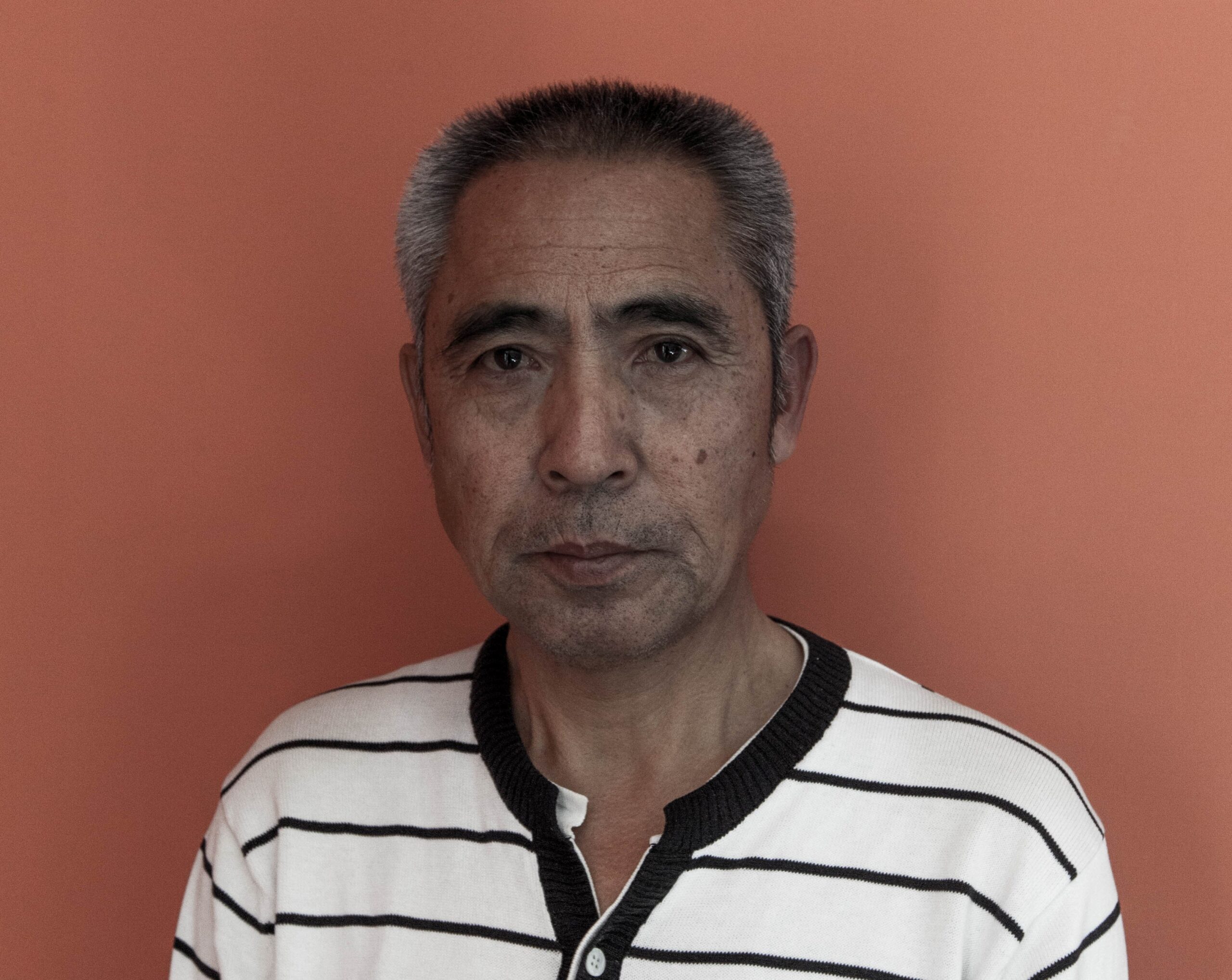

In 2023, Chinese authorities arrested prominent Southern Mongolian1 This term refers to Mongolians living in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region of China. The use of Southern Mongolian here reflects Lhamjab A. Borjigin’s preferences. Information on terminology used is included in the methodology section. writer and historian Lhamjab A. Borjigin at his residence in exile in the independent country of Mongolia and forcibly deported him back to China. His whereabouts following the deportation remain unknown.

His kidnapping underscores what the Chinese government has long known: that stories have intrinsic power, and that, in turn, controlling the narrative reinforces state power. Amongst several books Borjigin has written is his 2006 book, China’s Cultural Revolution, which compiles the oral testimony of survivors from the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region during the Cultural Revolution.

Borjigin’s story also exemplifies what Beijing has long sought to repress: the potential for digital technologies and spaces to magnify the impact of stories. In recent years, an audio version of the book circulated via WeChat had become highly popular among Mongolian listeners, both in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region in China and in the neighboring country of Mongolia.

The internet once offered a promising new site of dynamic cultural expression and community, including for ethnic minorities in China. Mongolians, one of 56 officially recognized ethnic groups in China, established a vibrant presence online. Sites using traditional Mongolian—a vertical script read left to right used in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, where the majority of Mongolians in China live—emerged, including local news sites, online discussion communities, local writers communities, cultural sites focused on heritage and music, and social media sites. From Holvoo to Boljoo, Mongolians began to express themselves online, discussing literature, linguistics, and traditional practices; and using traditional Mongolian script.

But even at this early stage, the growth of Mongolian culture online was regularly at odds with China’s extensive apparatus of digital control. While the Great Firewall blocked access to global platforms and censored politically sensitive content, Mongolian-language sites faced an even more precarious existence. Authorities routinely shut down forums, blogs, and voice chat rooms for alleged “separatist” content—even when those platforms focused on language preservation, cultural traditions, or educational resources. The closures reflected a deeper discomfort with autonomous Mongolian cultural expression that wasn’t state-directed or state-approved. Yet in response, Mongolian communities consistently adapted: creating new platforms, migrating conversations to new digital spaces, and developing creative ways to evade censorship. This push-and-pull between erasure and resilience has shaped the contours of Mongolian digital culture from the beginning.

In 2011, protests over the killing of a Mongolian herdsman, Mergen, by a Chinese coal mining driver marked an early example of how Chinese authorities used digital repression to control Mongolian dissent. Despite continued cultural development online, such as the launch of the Mongolian-language social media platform Bainuu in 2015, Mongolian expression increasingly clashed with the Chinese government’s push for “Sinicization.” The 2020 announcement of a new bilingual education policy, which severely curtailed Mongolian-language instruction in schools, sparked widespread protests that were met with mass detentions, censorship, coerced public “confessions” from protesters, and the shutdown of Mongolian digital platforms.

From 2020 onward, Chinese authorities intensified efforts to suppress Mongolian culture online. This included the closure of cultural sites, censorship of cultural terms and expression like websites and music, and surveillance of Mongolian communities (even those living abroad). The state has simultaneously erased Mongolian expression while promoting a sanitized version of its culture aligned with Chinese state narratives. By tightly controlling online communication and content, the government has violated Mongolians’ cultural rights and their creative expression, language, and identity as recognized under international human rights law. Free expression and cultural and linguistic rights are closely intertwined—free expression can only be fully respected when people are free to enjoy their cultural and linguistic rights. Mongolians have a vision of what true, free cultural expression online should look like. As one interviewee put it:

So to express ourselves online—that would mean telling our stories on our terms, in our own voice. It would mean Mongolian words, poems, and music thriving—not hidden in encrypted chats, not erased by algorithm or policy, not punishable. It would mean Mongolian children seeing their language in pixels as well as textbooks, feeling seen, alive, and proud.

Governments turn to cultural repression as a means to control the narrative, suppress dissent, and stifle freedom, and for ethnic minorities, wrestle away control of their identity. Beijing has silenced Mongolian voices and restricted their cultural rights, all the while expanding its arsenal of tactics to influence the information ecosystem and falsely present itself as respecting minority rights.

Stakeholders—including the United Nations, concerned governments, donors, cultural institutions, and technology companies—must stand in solidarity with Mongolians in China. Collectively, they should take forceful action to:

- Speak out and hold the Chinese government accountable for its human rights abuses against Mongolians in China, including cultural and linguistic rights violations, and increasing transnational repression

- Push back against efforts by the Chinese authorities to erase and control global narratives around their treatment of ethnic minorities like Mongolians in China, including through supporting independent reporting by news media and civil society on the Chinese government’s treatment of ethnic minorities; speaking out against Chinese government overreach into cultural institutions outside of China; and passing legislation to address transnational repression and harassment of exiled human rights defenders

- Promote Mongolian language and culture through financing cultural, linguistic, and educational initiatives and partnering with Mongolian communities, including overseas communities

- Support an open and free internet, including defending its core principles in internet governance forums and funding public interest technology that supports internet freedom; and

- Ensure cultural rights defenders are recognised as being at risk for their work and advocacy, and that they adequately supported and protected

Methodology

This case study focuses on Mongolians in China, most of whom live in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, an autonomous region in northern China that borders the independent country of Mongolia. The Chinese government’s extensive control over information in and out of China has made research in China, especially in the autonomous regions, increasingly challenging over the years. This control extends to cyberspace, in which users inside China operate on a Chinese digital ecosystem controlled and surveilled by the Chinese authorities. This control has restricted direct engagement with Mongolians still in China, and necessitated heightened precautions to protect sources and ensure researcher safety.

A further challenge for the research is the digitization of traditional Mongolian script. Users cannot read traditional Mongolian script without downloading specific programs which means sites archived on platforms like the Wayback Machine are often unreadable to non-Mongolian communities.

As a result, this case study is based on a mix of primary and secondary sources, including extensive reporting by the Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center (SMHRIC) and 20 interviews, conducted between May and December 2024, with Mongolians outside of China and experts on ethnic minorities and digital rights in China. Interviewees were chosen based on how recently they left the region and are not meant to be a representative sample, but rather intended to highlight particular examples of how Mongolian culture is being repressed online by the Chinese government. Identifying information related to the identities of interviewees has been removed for their safety.

To complement the interviews, the report also draws on academic research; media reporting including by news outlets like Radio Free Asia and Voice of America; and analysis of sensitive words on different platforms in China recently completed by Jeffrey Knockel of Citizen Lab. To map the availability of Mongolian sites, the research team used a combination of the Wayback Machine, IP ownership information, and interview evidence to identify when sites were opened, last available, and shut down.

The report refers to the region as the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region and to Mongolians who live there as Mongolians in China. Many Mongolians interviewed for this report refer to it as Southern Mongolia and themselves as Southern Mongolian, and quotes reflect their preferred terminology. Accordingly, their quotes may also refer to the independent country of Mongolia as Outer Mongolia.

Background

Mongolian Identity and Culture in Modern-Day China

Mongolians are one of 56 recognized ethnic groups in China and one of 55 recognized ethnic minority nationality groups (minzu). According to the most recent census in 2020, nearly 6.3 million Mongolians live in China, the majority of whom are in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. Established in 1947, two years prior to the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region was the first of five autonomous territorial regions with significant ethnic minority populations and nominal self-governance.2“How do China’s autonomous regions differ from provinces?”, The Economist, May 23, 2021, web.archive.org/web/20240201233201/https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2021/03/23/how-do-chinas-autonomous-regions-differ-from-provinces

In spite of Mongolians having a designated autonomous region and the associated rights, Mongolian people, culture, and identity have faced threats from almost the beginning of the PRC.

During the Cultural Revolution from 1967 – 1969, the People’s Liberation Army enacted a violent political purge against alleged “members” of the dissolved Inner Mongolian People’s Party. Official estimates by the Supreme People’s Procuratorate were that 346,000 people were arrested, 16,222 were killed, and 81,000 were injured or disabled.4“Crackdown in Inner Mongolia,” Human Rights Watch, July 1991, hrw.org/reports/pdfs/c/china/china917.pdf Additional scholarship estimates that at least 100,000 people were killed and 500,000 persecuted, estimates widely believed by Mongolians.5Kerry Brown, “The cultural revolution in Inner Mongolia 1967–1969: The purge of the ‘Heirs of Genghis Khan,’” Asian Affairs 38, no. 2 (2007): 173-187, doi.org/10.1080/03068370701349128 During this period, the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region was reduced in size as the borders were redrawn, giving land to neighboring provinces. Eventually this land was returned to the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region in 1979.6Thomas White, “Pastoralism and the state in China’s Inner Mongolia,” Current History 120, no. 827 (September 2021): 227-232, doi.org/10.1525/curh.2021.120.827.227

Following the Cultural Revolution, state policy continued to undermine Mongolian rights in the region. These included:

- State-controlled cultural representation—Authorities sought to “portray an idealized and curated image of the Mongolians and their pristine grassland…ready to welcome their Han ‘brothers and sisters.’”7Jesse Segura and Filka Sekulova, “Inner Mongolian poetry and song as a form of resistance,” Political Geography 115 (November 2024): 103214, doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2024.103214 Authorities also pursued the “museumification” of Mongolian culture, leaning on stereotypes to present a sanitized view of culture, distanced from independent expression.8Ibid.

- State-sponsored migration, resulting in significant demographic shifts—Throughout the 20th century, the Chinese government promoted Han migration, including bringing in migrant workers for mining, into the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region.9Thomas White, “Pastoralism and the state in China’s Inner Mongolia,” Current History 120, no. 827 (September 2021): 227-232, doi.org/10.1525/curh.2021.120.827.227; William R. Jankowiak, “The Last Hurrah? Political Protest in Inner Mongolia,” The Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs, no. 19/20 (1988): 269–88, doi.org/10.2307/2158548 In 1980, a development plan for the region made clear that Han migration would continue, sparking widespread student protests.10William R. Jankowiak, “The Last Hurrah? Political Protest in Inner Mongolia,” The Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs, no. 19/20 (1988): 269–88, doi.org/10.2307/2158548 Today, Mongolians comprise only 20 percent of the population of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region.

- Disincentivization of Mongolian fluency—The Mongolian taught in schools was perceived to be suited for pastoral life, traditional, and grassroots use, whereas Mandarin Chinese is perceived as the language of modernity and urban life. Economic opportunities further disincentivized mother tongue fluency: job opportunities tend to require fluency in Mandarin Chinese, and Mandarin Chinese is the primary language in the civil service and public institution system.11Disi Ai, Juup Stelma, and Alex Baratta, “The multilingual lived experience of Mongol-Chinese in China,” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 45, no. 9 (2024): 3662-3677, doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.2116450

- Policies that undermined traditional lifestyles of herding, agriculture, and pastoral nomadism—From the 1980s onward, economic policies, including forced urbanization, land confiscation, banning grazing, requiring fencing of livestock, and mining-related environmental degradation have all undermined traditional ways of life in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region.12William R. Jankowiak, “The Last Hurrah? Political Protest in Inner Mongolia,” The Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs, no. 19/20 (1988): 269–88, doi.org/10.2307/2158548

- Crackdowns on Mongolian activists, organizations, and cultural rights defenders—in 1991, the Chinese authorities began a campaign against ethnic Mongolian intellectuals, including by cracking down on two organizations: the Ih Ju League National Culture Society and the Bayannur League National Modernization Society. Authorities claimed these groups—which had previously operated openly—intended to “undermine the unification of the motherland.”13“Crackdown in Inner Mongolia,” Human Rights Watch, July 1991, hrw.org/reports/pdfs/c/china/china917.pdf; “Continuing Crackdown in Inner Mongolia,” Human Rights Watch, March 1992, hrw.org/reports/pdfs/c/china/china2923.pdf In 1995, Chinese authorities detained and later arrested Hada, one of the founders of the Southern Mongolian Democratic Alliance, after which they detained more than 10 other Mongolian intellectuals. Mongolian activism has remained vibrant in the 21st century, but authorities continue to persecute cultural rights activists, from herders defending their land rights,14“Herders Take to the Streets, Four Arrested,” Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, May 23, 2011, smhric.org/news_378.htm to those using the internet to foster independent discussion.15James Anaya; Cases examined by the Special Rapporteur (June 2009 – July 2010),” A/HRC/15/37/Add.1, September 15, 2010, digitallibrary.un.org/record/690257?ln=en&v=pdf; “Southern Mongolian Dissident Detained and Put under House Arrest,” Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, November 16, 2010, smhric.org/news_310.htm

In its 2018 Concluding Remarks, the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) expressed concern over “reports of abuses by State authorities against ethnic Mongolians peacefully protesting against the confiscation of land and development activities that have resulted in environmental harm…and a significant reduction in the availability of Mongolian-language public schooling.” They also noted the loss of traditional livelihood and land as a result of economic development policies, insufficient compensation for such land loss, and inadequate informed consent practices.18Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, Concluding observations on the combined fourteenth to seventeenth periodic reports of China (including Hong Kong, China and Macao, China), CERD/C/CHN/CO/14-17, September 19, 2018, tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CERD%2FC%2FCHN%2FCO%2F14-17&Lang=en

In the context of this decades-long repression, the Mongolian language has become an increasingly essential expression of Mongolian identity and culture for the millions of Mongolians in China today.19“China Statistical Yearbook 2021,” China Statistics Press, accessed January 11, 2026, web.archive.org/web/20211112214228/http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2021/indexee.htm In contrast with independent Mongolia where Mongolian-speakers generally use the Cyrillic alphabet (although the Mongolian government is expanding efforts to revive traditional Mongolian script),20Although the general public still uses the Cyrillic alphabet, the Mongolian government has deepened its efforts to revitalize the use of traditional Mongolian. For more, see: Sumiya Chuluunbaatar, “The Complex Geopolitics of Mongolia’s Language Reform,” The Diplomat, April 22, 2024, thediplomat.com/2024/04/the-complex-geopolitics-of-mongolias-language-reform/ Mongolians in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region still use traditional Mongolian script, albeit to varying degrees.21“Who are Mongols and Where Do they Live?”, Hamilton Lugar School of Global and International Studies, accessed December 1, 2025, celcar.indiana.edu/materials/language-portal/mongolian.html, “China’s ethnic Mongolians protest Mandarin curriculum in schools,” Al Jazeera, September 1, 2020, aljazeera.com/news/2020/9/1/chinas-ethnic-mongolians-protest-mandarin-curriculum-in-schools. After decades of using Cyrillic, the Mongolian government has prioritized efforts to reintroduce traditional Mongolian script into widespread use.

In 2013 in response to (the independent country of) Mongolia’s nomination, UNESCO recognized traditional Mongolian calligraphy as intangible cultural heritage in need of urgent safeguarding. This designation underscores not only the historical and artistic value of the script—but also the urgency of protecting Mongolian language in China against assimilationist policies and digital invisibility and erasure.

In 2020, the Inner Mongolian regional government announced the introduction of a new policy that would further weaken Mongolian cultural identity. Beginning that September, all primary and secondary schools would transition from Mongolian language instruction to instruction in Mandarin Chinese in three subjects: literature, civic education, and history (the language protests following the announcement of this policy are discussed below). According to a Reuters report on a Q&A publicly posted by the regional educational authorities, the decree “reflect[ed] the will of the Party and nation … and the inherent excellence of Chinese culture and advances to human civilisation.”

This announcement was made in the context of an already constrained environment for Mongolian language and literature. In 2020 alone, two independent Mongolian magazines founded by local writers, Zarut Literature and Tegehan, were banned, and a ban was placed on the buying and selling of Mongolian books, including online. In an interview with Radio Free Asia, one Mongolian described how his WeChat transaction was stopped by police while trying to purchase a book.22[“The Literature Magazine of Jaruud Banner in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Was Banned, and Portrait of Genghis Khan in the School Was Removed,” (“内蒙扎鲁特蒙文学杂志被禁 校内成吉思汗画像下架”), Radio Free Asia, July 28, 2020, rfa.org/mandarin/yataibaodao/shaoshuminzu/ql2-07282020063029.html

Prior to this policy, bilingual and Mongolian-language instruction had been available to Mongolian students and families, and high school and college exams were conducted in Mongolian. The instruction and economic incentives did not reflect a true state embrace of the Mongolian language—what was taught was not designed to produce Mongolian intellectuals and professions and job opportunities tended to be in Mandarin Chinese,23Disi Ai, Juup Stelma, and Alex Baratta, “The multilingual lived experience of Mongol-Chinese in China,” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 45, no. 9 (2024): 3662-3677, doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.2116450 but the opportunities to maintain their mother tongue existed.

State Policy Towards Ethnic Minorities

The state’s approach and treatment of minzu is outlined by the Chinese constitution, adopted in December 1982, and the Law of Regional Ethnic Autonomy, adopted October 1984 and amended in 2001. Article 4 of the Constitution and article 10 of the Law of Regional Ethnic Autonomy guarantee the freedom to “to use and develop their own spoken and written languages” and to “preserve and reform” traditions, customs, and folkways. At the same time, however, they both underscore the unity of the Chinese state is paramount—and that autonomous regions are expected to uphold and reinforce this unity.24Article 4 of the Chinese constitution, article 5.

In 2000, the Law on the Standard Spoken and Written Chinese Language elevated Mandarin Chinese above all other languages, framing it as the language of modernization and development. In alignment with this position, the 2001 amendment of the Law of Regional Ethnic Autonomy included earlier integration of Mandarin Chinese instruction into the education system for ethnic minorities.25Beginning in the lower or senior grades of primary school, Han language and literature courses should be taught to popularize the common language used throughout the country and the use of Han Chinese characters. In 2010, a formal “bilingual education” policy for minority areas was introduced, emphasizing the primacy of Mandarin Chinese as the national language.26“China’s “Bilingual Education” Policy in Tibet,” Human Rights Watch, March 4, 2020, hrw.org/report/2020/03/05/chinas-bilingual-education-policy-tibet/tibetan-medium-schooling-under-threat

Academic research has identified additional key points that began to reflect a shift in ideology, including in 2004 and 2011 where scholars advocated for a new approach that prioritized a shared national identity above all.27Xiaojuan Zhao, Md Azalanshah Md Syed, and Rosya Izyanie Shamshudeen, “Unraveling narratives: Chinese official party media’s representation of Inner Mongolia amid reforms,” Newspaper Research Journal 45, no. 4 (2024): 492-531, doi.org/10.1177/0739532924128027

Under Xi Jinping—who became Party Secretary in late 2012 and President in 2013—policy towards ethnic minorities has embodied elements of this thinking.28James Leibold, “China’s Ethnic Policy Under Xi Jinping,” The Jamestown Foundation China Brief, October 19, 2015, jamestown.org/program/chinas-ethnic-policy-under-xi-jinping/ Sinicization, a policy of absorbing ethnic minorities into the dominant Chinese Han culture, has become explicit. Sinicization advances a Chinese national identity rooted in Han culture at the explicit expense of cultural identities of ethnic minorities, including their ability to participate fully in public life and their right to express their cultural traditions and practices and their religion.29Julia Bowie and David Gitter, “The CCP’s Plan to ‘Sinicize’ Religions,” The Diplomat, June 14, 2018, thediplomat.com/2018/06/the-ccps-plan-to-sinicize-religions/ In line with this conceptualization of ethnic minorities as part of the Chinese “family,” Xi has called for increased ethnic mingling, including incentivizing inter-ethnic marriage.30James Leibold, “Xinjiang Work Forum Marks New Policy of ‘Ethnic Mingling’,” The Jamestown Foundation China Brief, June 19, 2014, jamestown.org/program/xinjiang-work-forum-marks-new-policy-of-ethnic-mingling/

Alongside a unified national identity, “stability” and “national security” have been weaponized to enable rights violations against Tibetans, Uyghurs, and Mongolians, including mass arbitrary detention via “re-education” camps, cultural and religious persecution, and mass surveillance.31Avinash Godbole, “Stability in the Xi Era: Trends in Ethnic Policy in Xinjiang and Tibet Since 2012,” India Quarterly 75, no. 2 (2019): 228–44, doi.org/10.1177/0974928419841787; “China’s “Bilingual Education” Policy in Tibet,” Human Rights Watch, March 4, 2020, hrw.org/report/2020/03/05/chinas-bilingual-education-policy-tibet/tibetan-medium-schooling-under-threat, er-threat; “China: Religious Regulations Tighten for Uyghurs,” Human Rights Watch, January 31, 2024, hrw.org/news/2024/01/31/china-religious-regulations-tighten-uyghurs, Nuriman Abdureshid, “China pushes the ‘Sinicization of religion’ in Xinjiang, targeting Uyghurs,” Radio Free Asia, May 22, 2022, rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/sinicization-religion-05202022133914.html CERD expressed concern over how the “broad definition of terrorism, the vague references to extremism and the unclear definition of separatism in Chinese laws” has been used and could be used to criminalize ethnic minorities in China, specifically noting Mongolians, alongside Uyghurs and Tibetans, were at risk of being targeted. Research by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute has also documented the National Ethnic Languages Translation Bureau’s development of software to recognize and translate minority languages—including Mongolian—online in 2019 and 2020.32Fergus Ryan, Bethany Allen, Shelly Shihm Stephan Robin, Dr. Nathan Attrill, Jared Alpert, Astrid Young, and Tilla Hoja, “The party’s AI: How China’s new AI systems are reshaping human rights,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, December 1, 2025, aspi.org.au/report/the-partys-ai-how-chinas-new-ai-systems-are-reshaping-human-rights/

In September 2025, a new Law on Promoting Ethnic Unity and Progress was proposed to the National People’s Congress. Human Rights Watch analysis found that the proposed law “would provide a broad legal framework to justify existing repression and force assimilation of minority populations throughout the country and abroad.” The draft law reinforces the primacy of a shared, unified Chinese national identity, including Mandarin Chinese as the “national common language.” Educational institutions, enterprises, public institutions, and individual households are required to advance these goals of ethnic unity, as envisaged by the Chinese Communist Party.

Mongolian Culture Online

Since the first Mongolian-language site, “Mongol Soyol”, was established on the Chinese internet in May 2001,33Yanhua Bao, “On the Current Development and Problems of Mongolian Websites,” (“试论蒙古文网站发展现状及存在的问题), Social Sciences of Inner Mongolia: Mongolian Edition 1 (2010): qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=32916104 the internet has been both a promising and challenging space for Mongolian cultural expression. Mongolian sites offered a forum for Mongolians to discuss their culture and to connect, and to access information in their mother tongue, even if limited relative to the number of Mongolians online in China.34Mongolians have been able to use and participate in a limited number of websites and apps designed for traditional Mongolian script use, but otherwise, many Mongolians in China typically use the Mandarin-language internet. See more: Sarala Puthuval, “A language vitality assessment for Mongolian in Inner Mongolia, China,“ (paper presented at the 2nd Conference on Central Asian Languages and Linguistics (ConCALL-2), Bloomington, IN, October 7 – 9, 2016), 131-148, scholarworks.iu.edu/iuswrrest/api/core/bitstreams/76fde991-19d9-41c7-b80f-777d68d48c7d/content; Garidi and Zhao Xiaobing, “The Retrospect and Problems Analyzing of Mongolian Linguistic Information Processing,” Social Science of Inner Mongolia 2, doc88.com/p-293580246740.html Limited funding, challenges digitizing Mongolian, and the Great Firewall have both challenged and informed the development of independent Mongolian culture online.35Sources in 2013 and 2015 estimated that there were over 200 Mongolian-language sites on the Chinese internet, including blogs, news sites, and cultural sites. After this period, data is limited. (Sources: History of Chinese Ethnic Minority News, the fifth issue of Inner Mongolia Social Sciences magazine)

Early Mongolian Online Cultural Sites (2001 – 2011)

In the early 2000s, especially after 2007, various government bodies, individuals, organizations, and companies worked to create websites and apps using traditional Mongolian script, allowing Mongolians to use and participate in websites and apps designed for traditional Mongolian script. A diverse array of sites emerged, including sites focused on culture such as music, online discussion forums and blogs that discussed literature, art and other cultural issues, but also state-run news sites that shared information in traditional Mongolian. By March 2008, there were 61 sites in traditional Mongolian, and by June, 70.36“CNNIC: The 33rd Statistical Report on the Development of China’s Internet (Full Text)” (“《第33次中国互联网络发展状况统计报告》(全文)”), China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC), 2014, PDF on file. Two years later, there were 100.37“Mongolian Cultural Development Will Be Unfolded on the Internet,” Mongolian News Weekly, June 2010, PDF on file

Early sites that focused on culture included “Mongol Soyol” and “Eagle on the Grassland” (Talin Burud, launched March 18, 2004), which highlighted Mongolian music. Social groups launched websites focused on specific fields, such as Legal Service (Huuliin Joloo) and Orthopedic Medicine (Bariyaach Suljiyee). Other later additions included sites like Inner Mongolia Climate Bureau and Munkh Gal Search Engine.38Mengkjul, “Mongolian culture and new media – on “Holvoo.net,” (“蒙古族传统文化与新媒体 – 以好乐宝 HOLVOO.NET 蒙文博客网为例”), Inner Mongolia Journalism Review 2 (2014).

During this same period, the Chinese government also launched news sites publishing in traditional Mongolian script. In August 2006, the Chinese government launched the first news website to publish in traditional Mongolian script, “Hulunbuir Daily Mongolian News Network.”39Garidi and Zhao Xiaobing, “The Retrospect and Problems Analyzing of Mongolian Linguistic Information Processing,” Social Science of Inner Mongolia 2, doc88.com/p-293580246740.html Two years later, the Inner Mongolia Daily, a state-run media outlet, launched the “China Mongolian News Network” on September 28, 2008, as a comprehensive news platform. At the time of its launch, it had 36 channels. These outlets were not designed to expand Mongolians’ access to independent information, but rather to shape and control the narratives available to them within a state-managed media environment.

Discussion Forums and Blogs

Especially popular amongst Mongolians were vibrant blogging discussion forums, where Mongolians were able to participate in online communities focused on cultural topics in their own language, from robust linguistic discussions to herding, a traditional practice. These included chat rooms on bulletin board services40These are social spaces that were the precursor to modern forums and social media. that evolved into more modern platforms for discussion, blogging, and messaging like Qinggis.net, Holvoo.net, and Boljoo.net.41Sarala Puthuval, “A language vitality assessment for Mongolian in Inner Mongolia, China,“ (paper presented at the 2nd Conference on Central Asian Languages and Linguistics (ConCALL-2), Bloomington, IN, October 7 – 9, 2016), 131-148, scholarworks.iu.edu/iuswrrest/api/core/bitstreams/76fde991-19d9-41c7-b80f-777d68d48c7d/content

At the same time state media began to publish news online in Mongolian, the Chinese government via the local authorities in Inner Mongolia shut down independent websites and cracked down on online activity under a range of pretenses. They repeatedly shut down websites and chat rooms that featured discussions on Mongolian history, language, identity, and cultural pride—including debates over the legacy of Chinggis Khan,42Chinggis Khan is a transliteration for Genghis Khan. the erosion of Mongolian-language education, and ecological displacement.43“Mongolian Internet Forum Closed for Discussing Ethnic Problems,” Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, July 16, 2007, smhric.org/news_170.htm Authorities also explicitly discouraged or banned the use of the Mongolian language in voice chats and forums.44“Authorities Close Two Mongolian-Language Web Sites for Posting “Separatist” Materials,” Congressional-Executive Commission on China, October 28, 2005, cecc.gov/publications/commission-analysis/authorities-close-two-mongolian-language-web-sites-for-posting; “Two Internet Sites Shut Down in Inner Mongolia,” Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, May 11, 2006, smhric.org/news_124.htm In addition, online spaces that criticized Chinese government policies were labeled as promoting “separatism” or “violating state laws,” prompting censorship and closure.45“Internet forum shut down in Inner Mongolia,” Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, March 5, 2004, smhric.org/news_34.htm; “Two Inner Mongolian websites closed because of “separatist” content,” Reporters without Borders (RSF), October 3, 2005, rsf.org/en/two-inner-mongolian-websites-closed-because-separatist-content

While not exhaustive, the following list highlights major shutdowns—and examples of the creativity and resilience of the Mongolians who continuously rebuilt online community spaces.

- March 2004: The web hosting company shut down a popular Mongol site, Nutag, in response to allegations of “[violations of] state laws” by the Inner Mongolia Public Security Bureau. Originally established in 2002, “Nutag” was a popular online students’ forum discussing Mongolian culture, history, language, and literature.46“Internet forum shut down in Inner Mongolia,” Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, March 5, 2004, smhric.org/news_34.htm After the shutdown, Mongolian students began Ehoron, or “homeland,” in September 2004.47“Authorities Close Two Mongolian-Language Web Sites for Posting “Separatist” Materials,” Congressional-Executive Commission on China, October 28, 2005, cecc.gov/publications/commission-analysis/authorities-close-two-mongolian-language-web-sites-for-posting

- September 26, 2005: Just one year later, local authorities shut down Ehoron and the site of a law firm, Monghal48“Two Inner Mongolian websites closed because of “separatist” content,” Reporters without Borders (RSF), October 3, 2005, rsf.org/en/two-inner-mongolian-websites-closed-because-separatist-content (translated as “eternal fire”) for alleged “separatist content”. The alleged content related to posts on Ehoron criticizing the portrayal of Chinggis Khan in an animated Chinese TV show. Following the shutdown of Ehoron, Mongolian netizens moved to “Mongol Youth BBS.” Monghal had been preparing a lawsuit against the TV show’s producers. Days later, Monghal was allowed to reopen on October 2.49“Authorities Close Two Mongolian-Language Web Sites for Posting “Separatist” Materials,” Congressional-Executive Commission on China, October 28, 2005, cecc.gov/publications/commission-analysis/authorities-close-two-mongolian-language-web-sites-for-posting

- April 2006: Web administrators and local authorities shut down two bulletin board service chat rooms for “separatist” content.

- The hosting service, uc51.com.cn of Sina Net,50The hosting service, which is unavailable from the U.S., is https://bbs.51uc.com/. removed “Mongolian Net Communications” (Mengguzu Wangtong), a voice-to-text chat room, on April 23 when participants didn’t comply with an administrator’s April 19 directive to “stop using the Mongolian language when chatting since all Inner Mongolians are Chinese citizens and therefore their mother tongue should be Chinese.”51“Authorities Close Two Mongolian-Language Web Sites for Posting “Separatist” Materials,” Congressional-Executive Commission on China, October 28, 2005, cecc.gov/publications/commission-analysis/authorities-close-two-mongolian-language-web-sites-for-posting; “Two Internet Sites Shut Down in Inner Mongolia,” Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, May 11, 2006, smhric.org/news_124.htm

- On April 21, authorities shut down Mongol Zaluus BBS (“Mongol Youth BBS”). While allegedly closed for exceeding storage, SMHRIC was told by a former administrator that the authorities were concerned about “overseas separatists” who had collected information on sensitive issues, like the closure of eastern Inner Mongolia’s Mongolian schools, the worship of Chinggis Khan, and the anniversary of the Mongol nation.52“Two Internet Sites Shut Down in Inner Mongolia,” Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, May 11, 2006, smhric.org/news_124.htm The address was then re-directed to the “Mongol Homeland Forum,” a placeholder for the defunct site.53“Two Ethnic Minority Web Sites in Inner Mongolia Closed,” Congressional-Executive Commission on China, June 30, 2006, cecc.gov/publications/commission-analysis/two-ethnic-minority-web-sites-in-inner-mongolia-closed; “Two Internet Sites Shut Down in Inner Mongolia,” Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, May 11, 2006, smhric.org/news_124.htm

- July 2007: Home Place of Mongolia (mglzaluus.com), a site that both fundraised for Mongolian students, and also hosted discussions on culture, the grasslands and ecosystem, amongst other things. In response to discussions around state policies on ecological migration and decreasing Mongolian schools, the authorities shut the site down.54“Mongolian Internet Forum Closed for Discussing Ethnic Problems,” Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, July 16, 2007, smhric.org/news_170.htm

- September 2009: In advance of the National Holiday on October 1, authorities once again blocked access to Home Place of Mongolia. Authorities also shut three popular sites:

- MGLhun (Mongol People Chat Room, a voice chat room) was shut down with no prior notice and with no reasons given. The chat room convened interactive online discussions about Mongolian music, song, and poetry; Mongolian history and local customs.55“Continuing Shutdown and Blocks of Mongolian Internet Sites by Chinese Government,” Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, September 18, 2009, smhric.org/news_258.htm

- Mongol Ger Association (Mongol Yurt Forum, mongolger.net) was shut for 20 days for an alleged violation of “bei an,” a bureaucratic site registration process. Topics discussed on the site include Mongolian language, legal rights, rights to land, and independent Mongolia.

- Mongolian People (mongolhun.com), a site that shares resources for Mongolian students and workers in other parts of China, was also shut down for reasons related to “bei an.”

A number of ethnic Mongolian activists who began and/or administered these discussion forums were also arrested.

- Sodmongol is a human rights defender and was the webmaster of a now-closed Mongolian-language forum “Mongol Yurt Forum” (mongolger.net) where participants discussed alleged human rights violations against Mongolians in China. On June 13, 2009, he was detained for questioning related to the site. On April 18, 2010, Chinese police arrested him on his way to New York to attend the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. The next day, local police raided his home and confiscated his and his wife’s computers, laptops, and cellphones.56“Southern Mongolian Representative to United Nations Conference Arrested at Beijing Airport,” Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, April 23, 2010, smhric.org/news_287.htm In response to an official complaint filed by the Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, Chinese authorities claimed that Sodmongol was involved in “illegal publication” and “investigated according to relevant laws and regulations.” Since then, independent organizations have been unable to obtain further information about his status.57UN Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms of Indigenous People, “Report by the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights and fundamental freedoms of indigenous people, James Anaya; Cases examined by the Special Rapporteur (June 2009 – July 2010),” A/HRC/15/37/Add.1, September 15, 2010, digitallibrary.un.org/record/690257?ln=en&v=pdf

- Huuchinhuu Govruud58More about her work and life is available here: Southern Mongolian human rights defender, dissident writer and activist Huuchinhuu died,” Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, October 25, 2016, smhric.org/news_599.htm was a prominent Inner Mongolian activist, human rights defender, and writer. As part of her work, she administered multiple popular, now-closed Internet discussion forums, including the above-mentioned Nutag (nutuge.com), Ehoron (ehoron.com), and Mongol Yurt Forum (mongolger.net). In November 2010, she was arrested for her efforts to use the Internet to mobilize support for Hada.59“Southern Mongolian Dissident Detained and Put under House Arrest,” Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, November 16, 2010, smhric.org/news_310.htm

Herding and the Suppression of the 2011 Protests for Herdsmen Mergen and Zorigt

In May 2011, a Chinese coal driver hit and killed a Mongolian herdsman named Mergen who was defending his pastureland from a Chinese mining company. His death sparked widespread protests across the region, which the Chinese government suppressed by deploying large numbers of troops. Following the crackdown of the 2008 protests in Tibet and the 2009 Urumqi riots in Xinjiang, the state response to the 2011 protests in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region further exemplified the government’s strategy to disrupt communication and censor content to undermine cultural mobilization.

One day prior to large scale protests, a rap song dedicated to Mergen was published on the Chinese discussion site, WangPan115.com—and later removed due to its “controversial content.” Similarly, local media and Reporters Without Borders reported increased censorship of words related to the protest, newly shut down or unusable instant messaging apps, targeted harassment of bloggers and internet users, and removal of content related to the protest from blog sites.60“China urged to exercise restraint over Inner Mongolia protests,” Amnesty International, May 27, 2001, amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2011/05/china-urged-exercise-restraint-over-inner-mongolia-protests-2/; “Internet censorship stepped up in Inner Mongolia,” Reporters Without Borders (RSF), June 6, 2001, rsf.org/en/internet-censorship-stepped-inner-mongolia; “Witch-hunts Starts as Military Control Tightens in Southern Mongolia,” Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, June 4, 2011, smhric.org/news_389.htm During this period, Boljoo, the Mongolian-language messaging app, was shut down for two-weeks, allegedly due to “system updates.”61Image on file with PEN America.

In October, a second herdsman, Zorigt, who was active in protecting grasslands, was killed by a Chinese oil transport truck. Following his death, Chinese authorities shut down Mongolian-language websites once more, including Boljoo, Mongolian BBS, (mglbbs.net), and Mongolian language news site Medege (medege.com).62Chinese authorities shut it down for its failure to have “ICP (Internet Content Provider) registration”. The site is currently directed to a plain page with a short message in Chinese stating that “the site you are trying to access has been shut down due to its failure to have ICP registration in accordance with the Order No. 33 issued by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of the People Republic of China.” All of these sites were used for discussing and distributing information and news about Mongolian language, culture, and identity, including the deaths of these herdsmen.

On the day of closure, the founder and administrator posted a message on the site stating, “the site will be shut down until November 15 in accordance with the notice given.”63Joshua Lipes, “Authorities Down Websites Following Death,” Radio Free Asia, October 28, 2011, rfa.org/english/news/china/herdsman-10282011123024.html

Research by the digital investigations nonprofit Citizen Lab until 2014 identified the following sensitive keywords (words that trigger censorship) related to the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region and Mongolian culture. Of the 11 keywords, five—like Mergen, Xi Wu Qi, and Inner Mongolia Protest—reference the 2011 protests, which sought to defend herding, a key element of Mongolian culture.

- 蒙独 (Mongolian independence)

- 蒙古独立 (Independence for Mongolia)

- 莫日根 (Mergen)

- 西乌旗 (Xi Wu Qi, the region where Mergen protested the government. In English, this region is known as West Ujimqin Banner)

- 2011 内蒙古抗议 (2011 Inner Mongolia Protest)

- 内蒙古抗议 (Inner Mongolia Protest)

- 外蒙 (Outer Mongolia/Independent Mongolia)

- 内蒙古人民党 (Inner Mongolia People’s Party)

- 蒙藏委员会 (Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs Commission. An institution for Mongolian and Tibetan affairs, established by the Chinese Nationalist Party.)

- 杀害牧民 (Killing herders / Murdering herders)

- 储波 (Chu Bo, Party secretary of the IMAR)

App Development and Usage (2012 – Present Day)

Beginning in the 2010s, Mongolian developers began to create phone applications alongside websites. Developers, for example, began to work on the Holvoo app in 2012, enabling users to more easily access and create blogs on mobile devices. Following the launch of Holvoo, the China Mongolian News Network launched Golomt, a blog app. In November 2013, Boljoo, a messenger system and Internet discussion forum using traditional Mongolian script, launched its app.64Study on the Current Situation and Development of Mongolian New Media Bainu,” (“蒙古语新媒体Bainu的现状与发展研究”, The Paper, June 23, 2020, web.archive.org/web/20241213035106/thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_7965611

As with websites, local-state controlled media also developed apps, as part of the “One Province, One Newspaper, One Client” initiative, a state policy designed to consolidate information dissemination and strengthen government control over the media. In August 2014, Inner Mongolia Daily began to operate two apps: Inner Mongolia Mobile News and Hello Inner Mongolia (Sainu Ovor Mongol). These were also supervised by the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Network Information Office and the Autonomous Region Communications Bureau.65Garidi and Zhao Xiaobing, “The Retrospect and Problems Analyzing of Mongolian Linguistic Information Processing,” Social Science of Inner Mongolia 2, doc88.com/p-293580246740.html; Gegentuul Baioud, “Minority language on social media,” Languages on the Move, February 28, 2022, languageonthemove.com/minority-languages-on-social-media

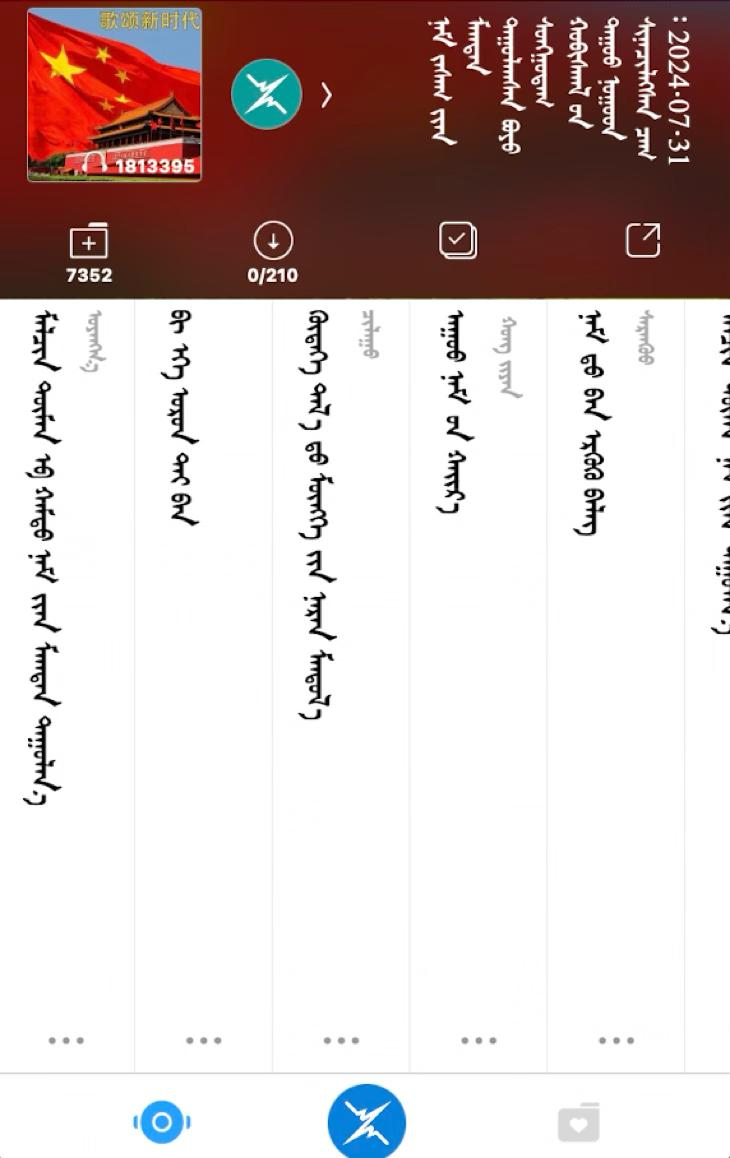

In January 2015, Inner Mongolia Zuga Software Company (Zuga) launched Bainuu (meaning “Are you there?”) on January 14, 2015. As of 2015, there were an estimated 400,000 users.66Gegentuul Baioud and Cholmon Khuanuud; “Linguistic purism as resistance to colonization,” Journal of Sociolinguistics 26, no. 3 (2022): 315-334, doi.org/10.1111/josl.12548

Today, Bainuu remains the primary Mongolian-language social media platform, and while subject to government control, still remains home to dynamic cultural expression, from discussing the Mongolian language, to vocalizing dissent, to mobilizing communities.67Gegentuul Baioud, “Minority language on social media,” Languages on the Move, February 28, 2022, languageonthemove.com/minority-languages-on-social-media/; “China Dissent Monitor: Issue 4: April – June 2023,” Freedom House, August 22, 2023, freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2023-08/CDM_4_Report_8_23.pdf WeChat, the most popular messaging platform in China, is also widely used by Mongolians in China, but users experience more issues with the Mongolian keyboards. Users must have the same keyboard script downloaded to read other users’ messages, otherwise messages are unreadable.68Avi Ackerman, “When AI doesn’t speak your language,” Coda Story, October 20, 2023, codastory.com/authoritarian-tech/artificial-intelligence-minority-language-censorship/

Since 2011, Chinese authorities have also targeted online chats and mobilization efforts for smaller-scale protests. In April 2019, authorities arrested an activist named Tsogjil and placed him into criminal detention for alleged “involvement in crime of picking quarrels and provoking troubles.” Tsogjil managed at least five WeChat groups with nearly 2,500 people, including one called “Language, Livestock and National Boundary.” Prior to his arrest, he had called on the group to demand the release of detained writer, O. Sechenbaatar. In June 2020, he, alongside another activist, Haschuluu, was sentenced for “rallying the public to petition the government, obstructing official business, videotaping and posting untrue stories, and transferring edited video footage to foreign organizations.”69“Two Mongolian activists sentenced to jail for defending herder’s rights,” Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, June 9, 2020, smhric.org/news_668.htm Tsojgil was sentenced to eight months, and Haschuluu, four months.

Challenges Digitizing Mongolian Script

The digitization of traditional Mongolian script has been a challenge throughout the lifespan of Mongolian online culture. The investigative outlet Coda reported that, because of the issues with Mongolian unicode, internet users have had to employ roundabout methods like taking photos of handwritten Mongolian to communicate over digital messaging apps or turning to a range of script programs that are often unable to interact with one another.70Avi Ackerman, “When AI doesn’t speak your language,” Coda Story, October 20, 2023, codastory.com/authoritarian-tech/artificial-intelligence-minority-language-censorship/ One widely used input method is the Menksoft Mongolia IME, which enables users to type and read in Mongolian scripts.

Challenges digitizing traditional Mongolian script have made it harder for Chinese censors to detect dissent or sensitive keywords, which, in turn, has seemingly fueled Chinese investments in language software such as Menksoft to enhance their censorship and surveillance capacity. According to the Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, the company and software have been taken over by a Chinese company supported by Chinese authorities. This includes script programs, but also machine learning systems that can detect handwritten Mongolian script.

At the same time, the obstacles to using Mongolian online also prevent community-members from using their own language in online spaces. Paired with economic and social incentives, younger Mongolians have increasingly been pushed towards Mandarin Chinese, the national language.71Avi Ackerman, “When AI doesn’t speak your language,” Coda Story, October 20, 2023, codastory.com/authoritarian-tech/artificial-intelligence-minority-language-censorship/; Sarala Puthuval, “A language vitality assessment for Mongolian in Inner Mongolia, China,“ (paper presented at the 2nd Conference on Central Asian Languages and Linguistics (ConCALL-2), Bloomington, IN, October 7 – 9, 2016), 131-148, scholarworks.iu.edu/iuswrrest/api/core/bitstreams/76fde991-19d9-41c7-b80f-777d68d48c7d/content

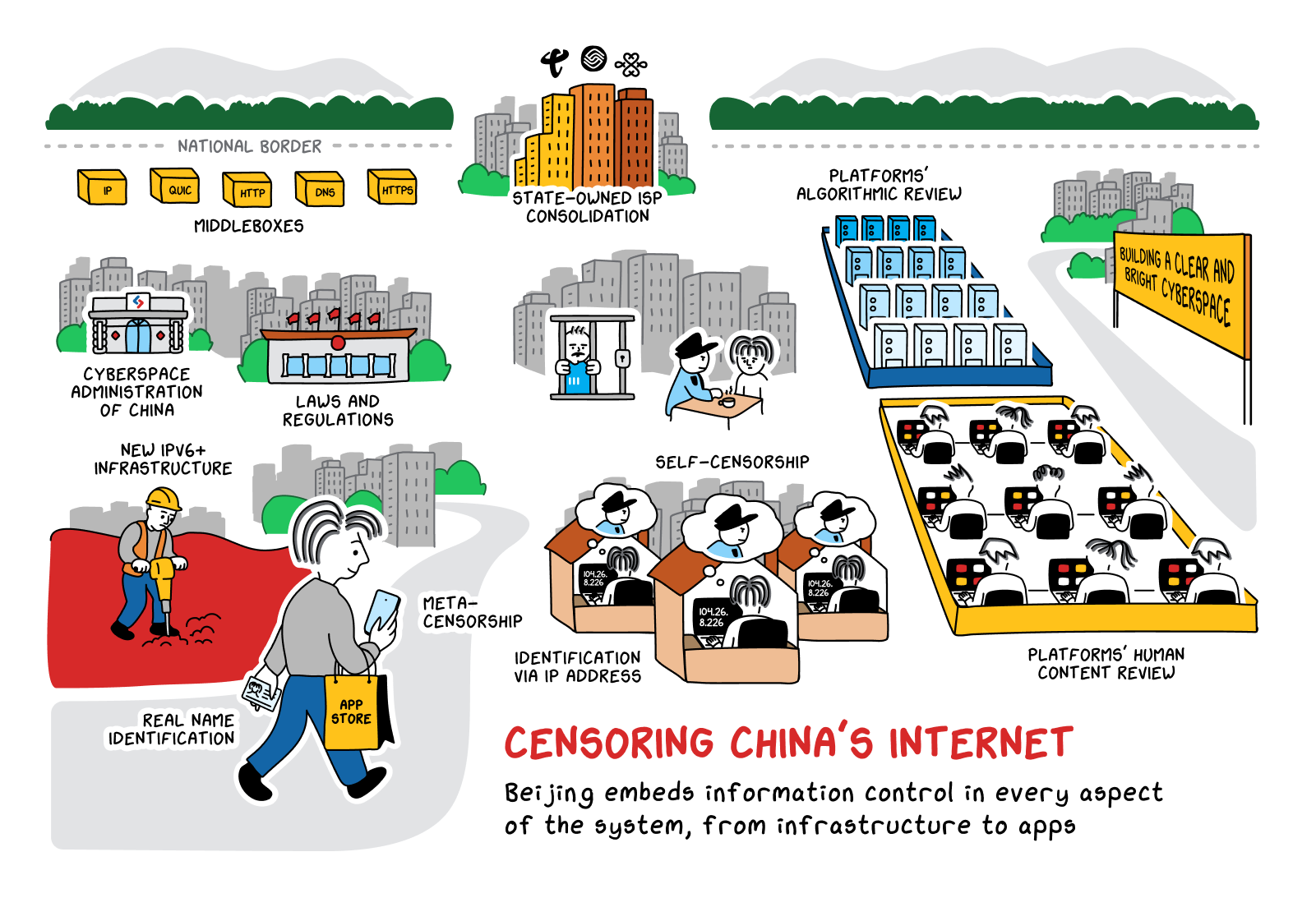

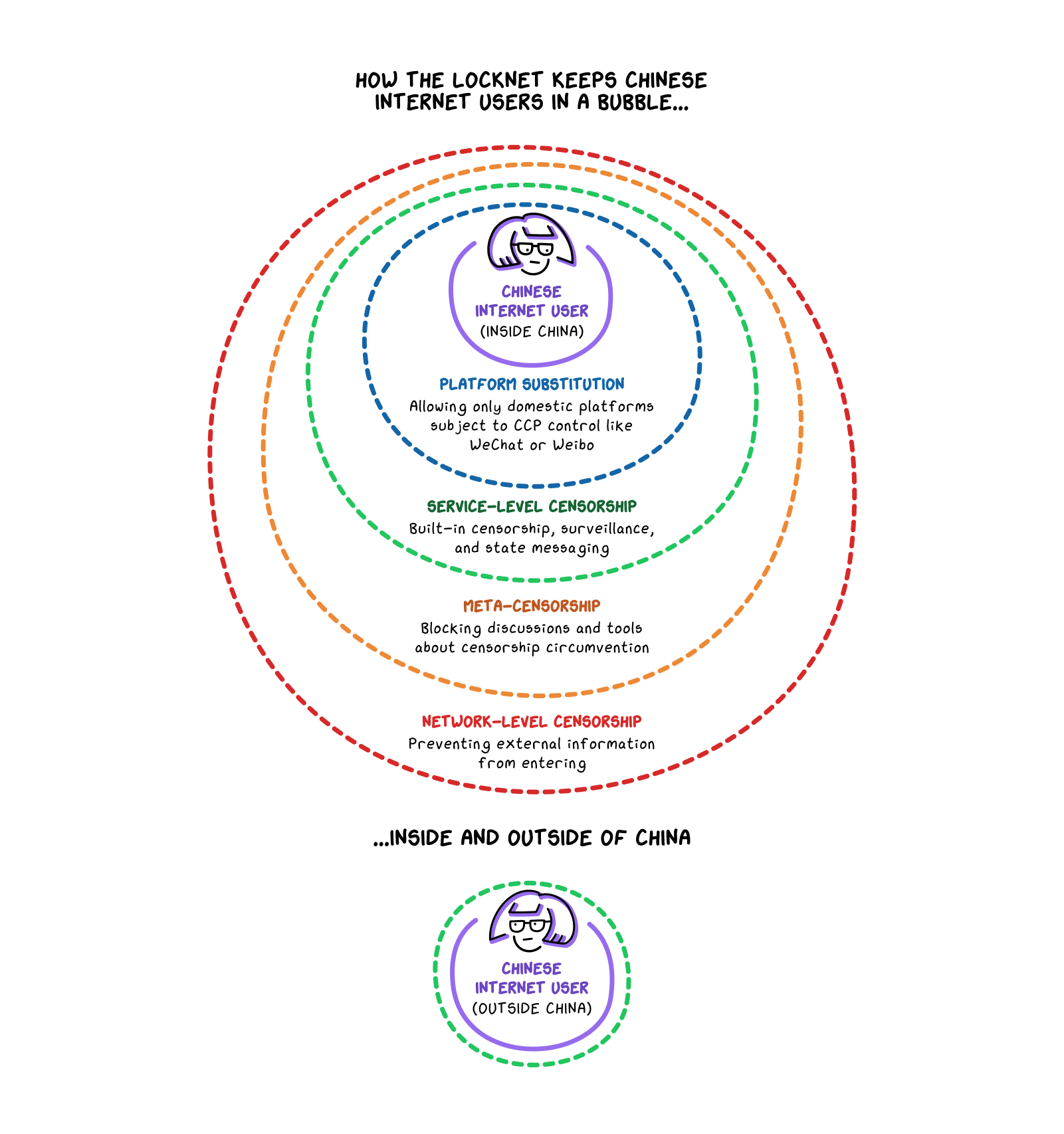

Internet Censorship in China

The Mongolian-language internet developed in the context of a technical, legal, and economic infrastructure that enables the Chinese government to censor, monitor, and control digital information, both within and beyond China’s borders. ChinaFile’s Locknet project outlines the tactics that underpin internet censorship in China—and more broadly information control, which includes a vast administrative and policy apparatus, enforcement by service providers, and technical tactics.

The laws governing forbidden content are vague, giving the Chinese government broad license to criminalize online speech. Since 2014, the Cyberspace Administration of China has overseen what constitutes illegal content through the Provisions on the Governance of the Online Information Content Ecosystem.72Jessica Batke and Laura Edelson, “The Locknet: How China Controls its Internet and Why It Matters,” ChinaFile, June 30, 2025, locknet.chinafile.com/the-locknet/part-1/ Alongside naming illegal content in Article 6, the provisions also identify encouraged content in Article 5 and negative content in Article 7. According to China Law Translate, illegal content, which “online information content producers [cannot] make, reproduce, or publish” includes the following:73“Provisions on the Governance of the Online Information Content Ecosystem,” China Law Translate, December 21, 2019, chinalawtranslate.com/en/provisions-on-the-governance-of-the-online-information-content-ecosystem/

- Content opposing the basic principles set forth in the Constitution

- Content endangering national security, divulging State secrets, subverting the national regime, and destroying national unity

- Content harming the nation’s honor and interests

- Content demeaning or denying the deeds and spirit of heroes and martyrs

- Content promoting terrorism or extremism

- Content inciting ethnic hatred or ethnic discrimination, or destroying ethnic unity

- Content undermining the nation’s policy on religions, promoting cults and superstitions

- Dissemination of rumors, disrupting economic or social order

- Obscenity, erotica, gambling, violence, murder, terror or instigating crime

- Content insulting or defaming others, infringing other persons’ honor, privacy, or other lawful rights and interests

- Other content prohibited by laws or administrative regulations

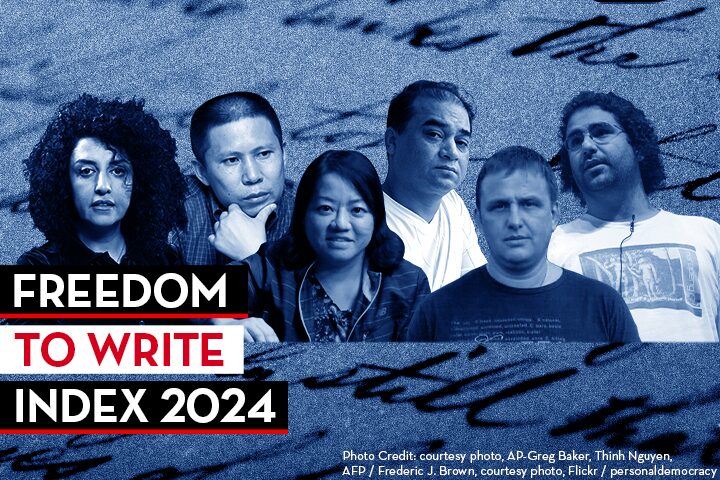

Chinese authorities weaponize these broad categories to suppress dissent. In 2024, PEN America’s Freedom to Write Index found that the number of writers jailed in China rose again, jumping from 107 cases to 118—around a third of whom are primarily online commentators, whose content is governed by these Provisions.

The Index also found that authorities continued to use national security to target writers for writing about topics including democracy, criticism of the CCP, and the promotion of ethnic minority languages and culture. Just under half of the imprisoned writers during 2024 were Uyghur, Tibetan, or Mongolian, often arrested and imprisoned for vague charges that allege “separatism.”74Liesl Gerntholtz, Karin Deutsch Karlekar, Asma Laouira, Hanna Khosravi, Anh-Thu Vo, “Freedom to Write Index 2024,” PEN America, April 24, 2025, pen.org/report/freedom-to-write-index-2024/#heading-6

The Chinese government maintains strong control over the underlying systems that power the Chinese internet, including providers, platforms, and users. Registration requirements link sites and accounts with real names and thereby enable the Chinese government to surveil users and respond to “illegal” content. Sites and their owners that fail to comply will have their site shut down. Mobile applications are also tightly controlled by the government: many apps available in other countries are blocked in China, and since 2023, all apps must receive official approval from the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology before they can be distributed or used.75Jessica Batke and Laura Edelson, “The Locknet: How China Controls its Internet and Why It Matters,” ChinaFile, June 30, 2025, locknet.chinafile.com/the-locknet/intro/?; Arendse Huld, “All Apps and Mini Programs to be Registered by End of March 2024 – A Quick Guide,” China Briefing, December 4, 2023, web.archive.org/web/20231214062815/https://www.china-briefing.com/news/china-mini-programs-app-registration-end-march-2024/ Similarly, users are required to register with their real identity. While this requirement was initially administered by platforms themselves, a new, nominally voluntary identity registration system administered by the government began in July 2025, making circumvention strategies like anonymity increasingly difficult.76“China: New Internet ID System a threat to online expression,” Article 19 and Chinese Human Rights Defenders (CHRD), June 25, 2025, article19.org/resources/china-new-internet-id-system-a-threat-to-online-expression/

Within China’s borders,77The 2017 Cybersecurity Law further strengthened this control, requiring any foreign company operating within China to store user data on servers located in China. platforms, such as search engines or social media sites, which must comply with these laws or otherwise be held liable, implement censorship rules based on their own interpretation of what constitutes illegal content and in response to government requests. On these platforms, human censors conduct the censorship, but they are also supplemented with automated censors. Academic research, including by centers like Citizen Lab of the University of Toronto, have identified sensitive keywords—essentially a blacklist of words—that trigger censorship of content. Research on search platforms showed that this censorship can be soft or hard. Soft means that search results returned are only from “authorized” sites whereas hard censorship means that no results are returned.78Jeffrey Knockel, Ken Kato, and Emile Dirks, “Missing Links: A comparison of search censorship in China,” Citizen Lab, April 26, 2023, citizenlab.ca/2023/04/a-comparison-of-search-censorship-in-china/ Alongside removing content, platforms will also report users. ChinaFile highlighted a concerning escalation where users face police questioning for even following a poster disliked by the authorities, citing a 2024 Wall Street Journal report on Chinese police questioning internet users who followed Teacher Li, an overseas dissident who verifies and posts Chinese news on X (formerly known as Twitter).79Shen Lu, “How a Chinese X User in Italy Became a Beijing Target,” The Wall Street Journal, March 6, 2024, archive.ph/BAPZB

In one example of platforms enforcing China’s censorship policies, China Digital Times reported on two apps removing Tibetan and Uyghur languages in November 2021. Talkmate, a language learning app, directly cited government policy as the reason for removing the languages from available languages to learn. On Bilibili, a video platform, one user’s attempt to use Tibetan and Uyghur in the comments returned an error message for “sensitive information.”80Arthur Kaufman, “Language Learning App Emphasizing Linguistic Diversity Deletes Tibetan and Uyghur Languages,” China Digital Times, November 2, 2023, chinadigitaltimes.net/2021/11/language-learning-app-emphasizing-linguistic-diversity-deletes-tibetan-and-uyghur-languages/

Both platforms and users face harsh consequences for violations, creating a climate of fear and self-censorship.81Yvonne Lau, “How China’s censorship machine feeds on fear,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, November 10, 2022, aspistrategist.org.au/how-chinas-censorship-machine-feeds-on-fear/ Companies can be fined or shut down, and individuals can and have been questioned, forced to confess, detained, or jailed—including for the act of having a banned app.82Ben Mauk, “Inside Xinjiang’s Prison State,” The New Yorker, February 26, 2021, newyorker.com/news/a-reporter-at-large/china-xinjiang-prison-state-uighur-detention-camps-prisoner-testimony

Beyond China’s borders, the Great Firewall controls information flows in and out of the country, using an array of techniques, including IP blocking, HTTP blocking, and restricting access to unapproved apps . Circumvention technology like Virtual Private Networks (VPNs), which would enable internet users in China to bypass the Great Firewall and access information beyond the Chinese internet, are restricted by technical and legal measures.

These two images, designed by ChinaFile’s Locknet83Graphics licensed under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license. See: Jessica Batke and Laura Edelson, “The Locknet: How China Controls its Internet and Why It Matters,” ChinaFile, June 30, 2025, locknet.chinafile.com/the-locknet/intro/? project visualize how censorship works and how it interacts with internet users inside and outside of China.

The lefthand image describes the vast array of tactics used to control the information ecosystem in China.

The righthand image is “adapted from the testimony of Nat Kretchun, of the Open Technology Fund, in his testimony to the U.S. Congress Select Committee on the Strategic Competition between the United States and the Chinese Communist Party, July 23, 2024.” This image shows how the average internet user experiences the censorship system.

Copyright: ChinaFile, a project of the Asia Society. This website is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Language Preservation Under Attack: 2020 and Beyond

I participated in the protests in Inner Mongolia in 2020, driven by my deep concern for the preservation of our language and culture. The atmosphere was charged with hope, but that quickly turned to fear as the government cracked down on dissent. I witnessed the intimidation of my fellow citizens, forced confessions, and the tragic loss of life, including the suicide of Su Rina [local official], which shook our community to its core. The government’s response to our protests was brutal; they implemented widespread censorship, shut down social media, and silenced anyone who dared to speak out.

– Mongolian teacher84PEN America interview with Mongolian teacher (13), 2024

In summer of 2020, news began to spread that on September 1, Mandarin Chinese would replace Mongolian as the main language of instruction in schools.85“Southern Mongolia: Mother Tongue to be Removed from Schools,” Unrepresented Nations & Peoples Organization, August 20, 2020, unpo.org/southern-mongolia-mother-tongue-to-be-removed-from-schools/ Seen as an effort to further chip away at one of the last vestiges of Mongolian identity, the Mongolian language, the policy galvanized one of the largest protest movements in Inner Mongolia’s 70+ year history.

As the start of the school year approached, thousands of Mongolians took to the streets to protest and defend their language and cultural rights. An estimated 300,000 students boycotted class, food delivery workers printed “Save our Mother Tongue” on delivery boxes, and government workers of Mongolian ethnicity sent petitions urging the government to reverse the plan, stating that the new policy was “[violating] the Chinese constitution, sabotaging ethnic harmony and creating national division.”86“Wanted posters issued, Mongolian staff of CCP mouthpieces prepare to resign en masse,” Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, September 3, 2020, smhric.org/news_677.htm

Chinese authorities employed a wide array of repressive tactics to suppress and end the protests, including “mass arrest, arbitrary detention, forced disappearance, imprisonment, house arrest, ‘concentrated training,’ termination of employment, removal from official positions, blacklisting and expulsion of students, suspension of social benefits, confiscation of properties and denial of access to financial resources including bank loans.”87“Activists face imprisonment and police stations in schools,” Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, October 18, 2020, smhric.org/news_683.htm By October 2020, the Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center estimated that between 8,000 – 10,000 Mongolians had been placed in some form of police custody during this protest period.88“Activists face imprisonment and police stations in schools,” Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, October 18, 2020, smhric.org/news_683.htm

As in 2011, authorities took significant measures to censor protest content89PEN America interview with Mongolian interviewee (1), 2024. and restrict access to online communities during the 2020 protests. Authorities also used their jurisdiction over the online space to create a climate of fear, heightening the costs for those defending their linguistic rights online, including prominent cultural rights activists.

Restricting Access to Online Communities

Mongolians used WeChat and Bainuu to organize protesters and galvanize resistance. Videos of storytellers, students, and protesters circulated widely.

The crackdown was swift. In August 2020, Chinese authorities began targeting online communication on messaging apps like Bainuu and WeChat. On August 23, Chinese authorities shut down Bainuu, first disabling chat groups, then wiping timelines and walls. At the time, Bainuu hosted around 400,000 users.90“Social media crackdown intensifies as Southern Mongolian protests escalate,” Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, August 24, 2020, smhric.org/news_672.htm

During this period, protesters were agile, shifting between messaging apps as restrictions tightened. On WeChat, group discussions and virtual gatherings were disabled, while other platforms, such as Potato, were blocked outright.91“Activists face imprisonment and police stations in schools,” Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, October 18, 2020, smhric.org/news_683.htm

On September 2, 2020, the government shut down the internet in the cities of Hohhot, Baotou, Wuhai, Alxa, and Bayannur cities.92Weibo notice, dated September 20, 2020. Photo on file. According to the 2020 Census, this would affect 3,446,100 internet users. According to the Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, the shutdowns lasted between three days to one week. Altogether, these cities comprise over one-third of the population in Inner Mongolia.

Censored Content

Alongside cutting off access to the internet and online communities, content related to the policy was widely censored.

Articles and videos that discussed the “bilingual education policy” in advance of its implementation became and remain unavailable.93“China’s new bilingual education policy in Inner Mongolia sparks controversy over minority rights” (中國內蒙古雙語教學新政引發少數民族權利爭議), BBC News, August 26, 2020, web.archive.org/web/20201103122614/https://www.bbc.com/zhongwen/trad/chinese-news-53959796 A speech by Professor Chimeddorj, Vice President of Inner Mongolia University and Dean of the School of Ethnology and Sociology of Inner Mongolia University, was initially posted on CCTV but later deleted. A July 2020 Mongolian Culture Weekly article by Professor Yang Tugusbayar, Mongolian Studies Professor, was also blocked after being widely re-posted.

Similarly, in late August, research by SMHRIC found that Chinese authorities began to increasingly monitor social media messaging apps and censor conversation and posts protesting the policy across platforms like WeChat, Bainuu, and Douyin. Examples of removed content include:94Photos on file with PEN America and the Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center

- Posts calling for Mongolians to stay strong, united, and peaceful in their protest

- Posts urging Mongolian families to keep their children at home in protest

- Cartoons protesting the policy and its cultural erasure

- Images comparing textbooks and the removal of Mongolian history

- Videos and images of Mongolian culture being visibly erased from architecture, including Mongolian script torn down from buildings, tablets depicting Mongolian history being painted over, and monuments being knocked over

- Posts of overseas outlets reporting on the protests

- Videos of in-person and digital protests

Targeting Cultural Rights Defenders

The Chinese authorities leveraged their control over the internet to target cultural rights defenders, from prominent cultural rights activists, to the Mongolian students, educators, and others that protested in the streets.

During the protests, authorities cut off the internet access and mobile connectivity of prominent cultural rights activists, including:

- Xinna, Mongolian activist and the wife of Hada,95“China: Freedom on the Net 2021,” Freedom House, September 2021, freedomhouse.org/country/china/freedom-net/2021

- Mr. Lhamjab Borjigin, author of “China’s Cultural Revolution”;96“Activists face imprisonment and police stations in schools,” Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, October 18, 2020, smhric.org/news_683.htm and

- Mr. Sechenbaater, dissident writer97“Activists face imprisonment and police stations in schools,” Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, October 18, 2020, smhric.org/news_683.htm

On Xinna’s last Facebook post, she wrote on October 21, 2020: “The Internet has been disconnected until now, but I can finally go out and surf the web! Since August 29, the Internet at my mother’s home in Baotou was suddenly cut off, and soon after, both my mother’s and my mobile phones were also disconnected. My mother has been picked up by my aunt, who lives in Tianjin, to stay for a while. At least now I can take a break!

On October 10, I returned to Hohhot. On my way home from the train station, I saw a white slogan, “Protect the Mother Tongue,” written in Mongolian on the glass window of a private car. Even though the authorities have used violence to suppress Mongolian resistance in the region, every Mongolian is deeply angry. This emotion will eventually explode.

Since the Internet at home in Hohhot has been disconnected, both my son’s and my phones have been cut off. We had to go out to find a way to get online. I spent more than a month browsing information on the Internet, and now I want to share the story of being under house arrest after the Internet shutdown. The title of my next post will be: “On September 1, my mother and I went to Assembly Square and were intercepted in a taxi by the National Security Bureau!” (October 21, 2020, 11:52 AM). This is the photo we took at home after being intercepted by the police.

Alongside prominent cultural activists, authorities targeted Mongolian protestors advocating for their cultural rights. An estimated 450 protesters who shared information about the so-called “bilingual education” policy online were “warned by local state Security and Public Security authorities…not to spread information…online.”98“Social media crackdown intensifies as Southern Mongolian protests escalate,” Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, August 24, 2020, smhric.org/news_672.htm At the end of August, one Mongolian named Oyuungerel reported on WeChat that “at least 28 people in our WeChat groups, mostly consisting of concerned parents and students, were either summoned or visited by State Security personnel in a single day.”99“Social media crackdown intensifies as Southern Mongolian protests escalate,” Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, August 24, 2020, smhric.org/news_672.htm

Local authorities also used social media and digital surveillance to publicly target Mongolian protesters.

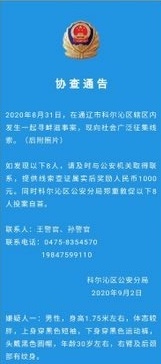

On September 2, 2020, authorities in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region issued multiple wanted posters for Mongolian protesters on the WeChat subscription pages of local Public Security Bureau branches—all under the politically-motivated claim that they had spread “false and harmful information on the internet.”100An example of a virtual “wanted poster” by the Keerqin District Public Security Bureau, a local public security bureau in the Iner Mongolia Autonomous Region: web.archive.org/web/20200903140213/https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/P26QhT1_LZyGoVL9i99Uww These posters called for people to report to the Public Security Bureau if they recognized any of the faces.

On September 5, 2020, the Yuquan District Branch of the Public Security Bureau in Hohhot City, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, issued a notice about the detention of someone101This lack of detail is standard for WeChat notices by public security bureaus. who posted about the use of state-issued Chinese textbooks in a WeChat group.102The Paper, “Hohhot police: One person detained for posting false information about the use of nationally compiled textbooks in a WeChat group,” Sina News, September 5, 2020, news.sina.cn/2020-09-05/detail-iivhuipp2633854.d.html The police detained him for five days, citing violations under Article 25 of the “Public Security Administration Punishment Law of the People’s Republic of China,” and used him as a warning to other protesters.

The “Notice” warned that some individuals in the city had been influenced by “ulterior motives” to spread false and harmful information about the state issued Chinese textbooks. To maintain social order and protect public safety, the Public Security Bureau announced its intention to strictly enforce the law against various illegal activities, including:

- Distorting policies and inciting the public to disrupt social order, attack state organs, or cause traffic disturbances.

- Fabricating and spreading rumors or false information online.

- Provoking disturbances through threats, insults, or by inciting students to strike.

- Organizing or participating in illegal assemblies, parades, or demonstrations.

- Using violence to obstruct law enforcement or hinder public officials from performing their duties.

- Committing acts of violence, illegal detention, or damaging public or private property.

- Engaging in other illegal acts that threaten national security or public order.

Interviewees also described the harassment of their loved ones, including those outside of China, due to their participation in protests.

Using Social Media to Harass and Intimidate

At the same time authorities restricted online communication, they also used social media to create a climate of fear.

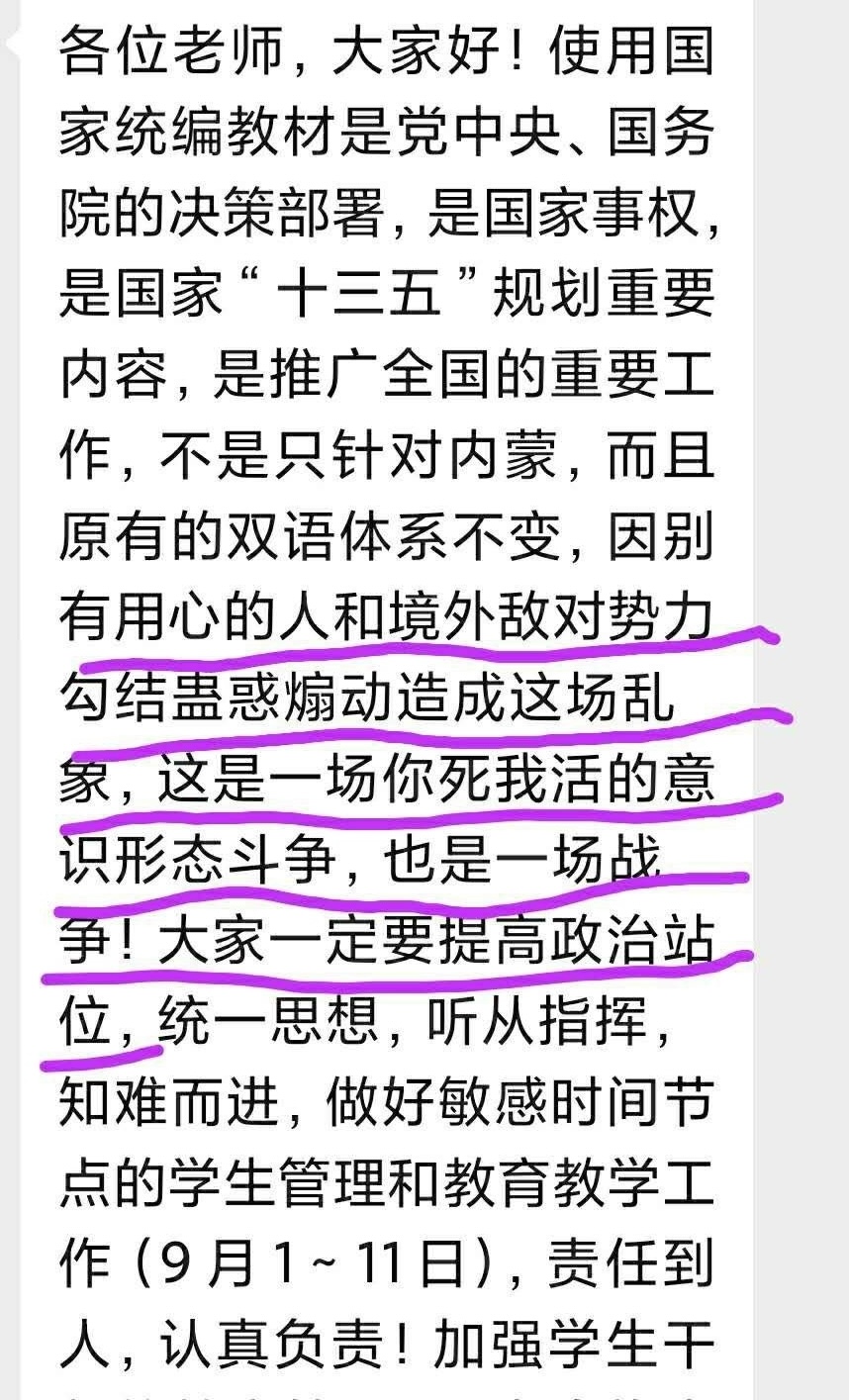

In one message distributed to teachers on social media on August 26, 2020, authorities denied the impacts of the new education policy, framed protests as a result of “people with ulterior motives and foreign hostile forces” and an “ideological struggle,” and outlined the consequences for any teachers participating in the protest, including reduction of wages—a threat previously used in the crackdown of the 2011 protests.

Dear teachers, hello everyone! The use of national standardized textbooks is a major decision made by the Central Committee of the Communist Party and the State Council. It is a matter of national authority and a key part of the national “13th Five-Year Plan.” It is an important measure promoted nationwide, not only targeted at Inner Mongolia. The original bilingual education system remains unchanged. Certain people with ulterior motives, both domestic and abroad, are stirring up trouble and inciting emotions to create this chaos. This is an ideological struggle of life and death — it is a war! Everyone must raise their political awareness, unify thinking, obey orders, overcome difficulties, and do a good job in student management and teaching during sensitive periods (September 1–11). Take responsibility seriously! Strengthen student management! The Party Committee, public security, prosecutors, and courts have all formed special task forces and are now stationed in our school. Because this is a war, not a minor issue. Anyone involved in this incident who is a salaried employee will be dismissed and have their wages terminated, and will be dealt with strictly. So everyone must do their best at work, manage your classes and classrooms well. If you notice any abnormal teacher or student behavior, report it to the school immediately. Let us work together to win this ideological battle! Please confirm if you receive this message!

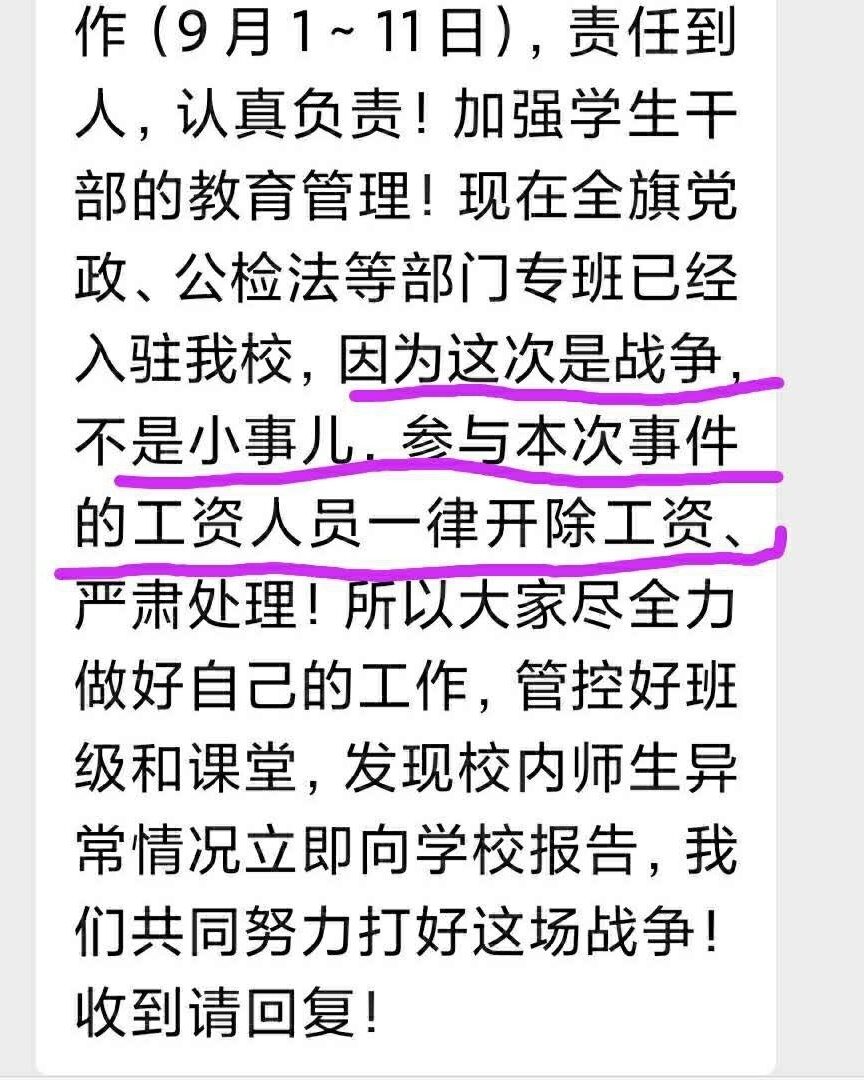

In another case, one notice circulated at Inner Mongolia Normal University during the protests instructed staff to complete a WeChat Group Chat and Work Email Survey. This guidance required staff to monitor and regulate community channels, disband unused groups, and enforce strict security protocols, and provide information directly to local authorities.

Summary of Notice on Survey of WeChat Groups and Work Emails

All colleges and departments are required to conduct a thorough survey of the number of WeChat groups and work emails used for transmitting work information, in compliance with the guidelines from the Cyber Security and Information Committee. Key actions include:

Survey and Management: Identify and manage all WeChat groups and work email accounts. Disband unused groups, cancel accounts of non-employed personnel, and delete content containing sensitive information.

Safety Management: Implement strict management protocols for WeChat and email communications, ensuring proper authentication of users and managers. Avoid weak passwords, and refrain from using work emails in insecure environments.

Confidentiality Standards: Clearly define and adhere to the boundaries between state secrets, work secrets, and public information. Important documents should not be shared via these platforms.

Accountability and Awareness: Strengthen network security awareness across all departments. Assign responsibilities for network security, and enforce serious consequences for breaches of confidentiality that result in significant adverse effects.

Action Required:

Each unit is required to complete and submit the “WeChat Group Chat and Work Email Survey Statistics Table” by 12 noon on September 29, 2020.

The completed form, stamped with the unit’s official seal, must be submitted to the Comprehensive Section of the Party and Government Office by midnight.

Contact Information (Redacted)