The PEN Ten: An Interview with Zak Salih

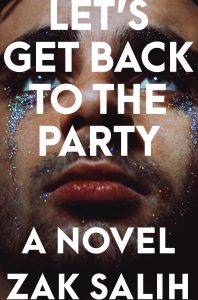

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Jared Jackson speaks with Zak Salih, author of Let’s Get Back to the Party (Algonquin Books, 2021).

Photo by Emily Poland

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

Thinner by Stephen King. Not my favorite King novel by any means—that honor likely goes to It or The Stand—but it was the first of his I ever read. I recall taking the paperback off my mother’s nightstand sometime in 1997, simply because I needed something to read on a car ride and was out of fresh comic books. I was enraptured by the imagination, the apparent ease of King’s storytelling, and, okay, the morbid pessimism of it all. I soon found myself devouring other King novels, then King-adjacent novels, and then one day I sat at my father’s electric typewriter and wondered if I could tell stories just like him. I credit Thinner—and King—as the bridge between my old obsession with comic books and my current obsession with novels.

2. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

I grew up in a house of rules and schedules: homework times, dinner times, bed times. As fascist an environment as that seemed to be as a young child, it’s likely responsible for how scheduled my creative process is. I treat writing like an office job, in the sense that I show up every morning at my desk for three hours—even if the writing is minimal (or poor), it’s enough for me to stare at a Word document and pretend to be busy. And like an office job, I don’t usually write on weekends (or federal holidays). Having some breathing room to simply think about a writing project is, for me, just as important as sitting down to draft it. Often, these “breaks” end up creating a momentum of their own, so that come Monday morning, I’m eager to sit down and get back to work. Usually.

“Over the four years from drafting the first pages to the final book appearing on shelves, I could persevere through so much doubt and anxiety and impatience and rejection. I left a comfortable full-time job to write a novel and see if someone would publish it, so whatever the public reception of Let’s Get Back to the Party, I can say unequivocally that I did what I set out to do.”

3. What is one book or piece of writing you love that readers might not know about?

Are people more familiar with the Sudanese novelist Tayeb Salih’s novel, A Season of Migration to the North, than I think they are? If not, they should be. It’s a slim novel that’s part riff on Heart of Darkness, part reverse colonization revenge fantasy. I talk up and write about the novel every chance I get, so much that I paid homage to its brilliant ending in my own. I suspect part of my infatuation for A Season of Migration to the North is from the pride I feel in having links to the culture the author describes—not to mention our shared surname.

4. What was one of the most surprising things you learned in writing your book?

That I was capable of doing it. That I could be creative and productive amid so much uncertainty. That, over the four years from drafting the first pages to the final book appearing on shelves, I could persevere through so much doubt and anxiety and impatience and rejection. I left a comfortable full-time job to write a novel and see if someone would publish it, so whatever the public reception of Let’s Get Back to the Party, I can say unequivocally that I did what I set out to do. There’s an overwhelming pride in that accomplishment alone, along with muscle memory that will hopefully keep me fit during future doldrums, writing or otherwise.

5. When did you first call yourself a writer? How did it feel?

So much of my journey as a writer has mimicked my earlier journey in coming out, in the sense that for a long time, I would hesitate to call myself a “writer” out of shame. There was—and sometimes still remains—something vulnerable about telling people “I write fiction,” rather than “I write marketing and advertising copy.” The latter seems more publicly acceptable (read: economically productive) than the former. But the truth is that I’ve been a writer since I was a child, whether I called myself one or not. I was a writer as a boy typing out nonsensical stories in my parents’ basement; I was a writer in graduate school trying to cram literary theory into exam papers; I’m a writer now answering these questions.

“So much of my journey as a writer has mimicked my earlier journey in coming out, in the sense that for a long time, I would hesitate to call myself a ‘writer’ out of shame. . . But the truth is that I’ve been a writer since I was a child, whether I called myself one or not. I was a writer as a boy typing out nonsensical stories in my parents’ basement; I was a writer in graduate school trying to cram literary theory into exam papers; I’m a writer now answering these questions.”

6. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity?”

I’m not convinced my identity—as biracial, as gay—has as overt a control on my writing as people might expect. Perhaps my subconscious would disagree. The things that interest me as a reader and writer, that compel me toward literature, aren’t bound by the constraints of any one particular identity other than that of being a human. I try to follow my own intellectual and emotional preoccupations in my work, regardless of whether or not they’re “in the lane” of my particular identity. An individual’s relationship to a community, the passing of time, the fear of change and death—these things certainly intersect with the identities I claim, but they’re not exclusive to them.

7. What advice do you have for young writers?

Try as hard as possible to write—at least in the first drafting stages, unencumbered by the opinions of others. Fiction writing is an entirely subjective endeavor—frustratingly so. Given that, the only possible sense of objectivity can be the writer’s own taste and instincts. Does the story you want to tell call for the first person? Write it in the first person. Is the shape of your story a series of fragments, a dramatic monologue in a single unspooling sentence? Follow it, and see what happens. Leave the marketing to the marketing departments; that’s out of your control. The writer’s duty, it seems to me, is to write as uninhibited and ferociously as possible.

8. Writing is an intimate process. Your debut novel, Let’s Get Back to the Party, now also belong to readers. How do you prepare for that?

I know, I know: We’re tired of having novels compared to children and authors to parents. Still, you eventually send your work off into an uncertain world and hope you did the best job you could at providing for it. At a certain point, I had to step away from this novel and say, “I wrote the best novel I could with the skills and experience I had at the time.” It’s become a mantra for me in my moments of doubt, when thoughts turn to reading my Goodreads reviews.

“I like to think, in saner moments, that coming out of the closet all those years ago has prepared my emotional muscles for the unpredictability of publication. Pride as a gay man, as a writer—both require one to build up defenses against judgment while simultaneously embracing the vulnerability that comes from making public one’s authentic self.”

The publishing process is, at heart, an exercise in letting go. What readers find of value in the work, what meaning they make of it, isn’t up to you. I like to think, in saner moments, that coming out of the closet all those years ago has prepared my emotional muscles for the unpredictability of publication. Pride as a gay man, as a writer—both require one to build up defenses against judgment while simultaneously embracing the vulnerability that comes from making public one’s authentic self.

9. Let’s Get Back to the Party follows two childhood friends after a run-in years later at wedding. One friend, Sebastian, reflects on the evolution of gay identity and expression through a teacher-student relationship with one of his students. The other, Oscar, laments the change he sees within his community—particularly those who choose to pursue marriage—while developing a relationship with a prominent gay writer from the AIDS era. How did creating cross-generational friendships, on both ends of the spectrum, help examine the present-day politics at play in the novel, as well as the psychology of your two main characters?

9. Let’s Get Back to the Party follows two childhood friends after a run-in years later at wedding. One friend, Sebastian, reflects on the evolution of gay identity and expression through a teacher-student relationship with one of his students. The other, Oscar, laments the change he sees within his community—particularly those who choose to pursue marriage—while developing a relationship with a prominent gay writer from the AIDS era. How did creating cross-generational friendships, on both ends of the spectrum, help examine the present-day politics at play in the novel, as well as the psychology of your two main characters?

When I think of the novel’s four major characters lined up with one another, I’m reminded of that wonderful painting by Paul Gaugin titled Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?, which offers a panorama of sorts of the cycle of life and the passing of time. We all exist on a continuum, sandwiched between the past and the future.

The primary psychological dilemma for Sebastian and Oscar is that they don’t recognize this—they’re too overwhelmed by their own sadness and rage. The ways these middle-aged men perceive and interact with the writer, Sean, and the student, Arthur, offered a context in which I could touch on deeply political questions about how culture changes: Are we changing too fast? Are we changing enough? Are we changing in the right ways? Should we even change to begin with?

10. The novel is contemporary, set shortly after the Supreme Court marriage equality ruling and coinciding with the massacre at the Pulse nightclub. What made you want to write about queer life in contemporary America? How did you go about writing the recent past? Did challenges arise that you didn’t expect while including contemporary details—the joyous and tragic truths of today?

Writing about contemporary queer life offered me a way to interrogate my own feelings as part of a “hinge” generation of gay men living between the generation that suffered the brunt of the AIDS plague and the generation growing up now in a time of increased visibility (and acceptance). It’s an incredible responsibility—and a great challenge—to write about such an extreme swing of events, from a moment of public celebration to one of public trauma. But as Flannery O’Connor reminds us: We tell a story when a statement just won’t do. Writing the novel became much less daunting when I gave myself permission to just tell a story instead of write toward some bold, blanket statement about queer life in contemporary America—which I would argue is impossible anyway.

Zak Salih lives in Washington, D.C. His writing has appeared in Crazyhorse, The Chattahoochee Review, The Millions, The Rumpus, and other publications. Let’s Get Back to the Party is his first novel.