The PEN Ten: An Interview with Katherine Seligman

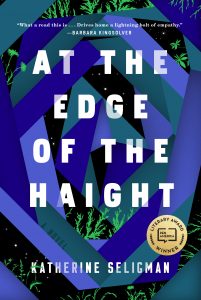

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Jane Marchant speaks with Katherine Seligman, author of At the Edge of the Haight (Algonquin Books, 2021).

Photo by Penni Gladstone

1. Where was your favorite place to read as a child?

I liked to read squeezed into a small space between a bed and desk. I spent so much time there that my parents finally put a cushioned chair in my room and I would sit on it, wrapped in a blanket. I lived a lot of my childhood in that chair.

2. What impact has winning the 2019 PEN/Bellwether Prize for Socially Engaged Fiction had on your life, either personal and/or professional? What advice would you give to writers looking to submit to prizes such as these?

When I’d finished writing the book—or as close as I could get—a good friend and fellow writer, aware of the difficult publishing landscape, suggested sending it to contests. I chose a few and was surprised when I won the Bellwether Prize, which Barbara Kingsolver has generously given out for 20 years. Actually, that’s an understatement—I was stunned. And honored that the judges believed in my book. I wish I had advice based on some new revelation, but I don’t. Write the book you’re intent on writing, and most of all—this is one we all hear, but it’s true—be persistent.

3. How did you come to this story, and how did you develop its plot?

One night, my husband and I were driving home through Golden Gate Park when a man jumped in front of our car, pleading with us to stop, yelling that someone was trying to kill him. When the police arrived, they shone a light onto the nearby lawn, and we saw the body of a young man who was gasping what was his last breath. They eventually let the killer go because there were no direct witnesses.

“Write the book you’re intent on writing, and most of all—this is one we all hear, but it’s true—be persistent.”

That night and the words of one cop stayed with me: “Neither one of them was up to any good.” Clearly, this wasn’t where the story of that kid started or ended. What about his family? Wouldn’t they want to know how he ended up in the park and what brought him in contact with his killer? I’d been a journalist for more than 20 years, living and writing from San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood, but this resonated in unexpected ways. How many people did we pass every day—including in our own family—with no idea what they were thinking? This, I decided, was the heart of the story.

4. How has your reading routine been affected by the events of 2020? Have you found yourself reading more, less, or different subject matter than before?

A month or so into the pandemic, I had a concentration crisis. I couldn’t focus on anything, so I decided to stop forcing it and went where my mind took me. I’d open a book, read a little, and put it down. Like a lot of people, I devoured the news and every magazine that came into the house, but it was harder to stay with fiction. Gradually, I did something I hadn’t in a while: went back to some favorite classics. Now, due partly to the inability to remain on high alert indefinitely—and the release of some books that made the rest of the world fall away—I’m back to my old pattern of reading and disappearing into stories.

5. Do you think a writer needs to have a personal or emotional connection to a subject they’re writing about to write socially engaged fiction?

That’s often where the seed of a story begins, with a subject that works its way into you in unexpected ways. That’s what happened with this subject. I don’t think the fundamental story needs autobiographical detail, but you have to follow the trail of what draws you in. It’s a curious mix of going toward the unknown, but with a sense that you know and understand the motivations and thoughts of the fictional characters you’re writing about.

“I don’t think the fundamental story needs autobiographical detail, but you have to follow the trail of what draws you in. It’s a curious mix of going toward the unknown, but with a sense that you know and understand the motivations and thoughts of the fictional characters you’re writing about.”

6. How important is research and journalism to writing socially engaged fiction, and how does your writing navigate truth? Why does fact need to be turned into fiction?

My novel was inspired by a real event, and people have asked me why I wanted to fictionalize it. I thought a lot about this as I was researching, looking through court records, and talking to people. For me, what it came down to was finding a way to write about the themes that the event evoked. I didn’t set out to write a novel about homelessness, but I wanted to explore how we can know so little about people in such close proximity to us. Research is essential, but once that’s done—and there are so many rabbit holes to do down—so are the truths we carry and know, beyond what’s possible to look up.

7. Who did you meet, and who did you talk to while writing this book? What was one of the most surprising things you learned while writing it?

Over more than 25 years living in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury, I’ve met a lot of people who were passing through, living in the nearby park or on the street. But the neighborhood, and the surrounding city, changed a lot during that time. It still draws drifters, seekers, and travelers, but they find a different landscape—where it’s harder to find stable, affordable housing. There are fewer artists, musicians, teachers, and old hippies and more people who work in the tech economy.

During the years spent writing the book, there were a number of young people who generously spoke to me about their lives. I also talked to the police and to people working to help the homeless. What surprised me was how differently they perceived the same events. No one agreed on exactly what happened.

8. Your book grapples with ideas of what it means to be lost and what it means to be found. When in your life have you yearned for either, and have there been times when as a writer you’ve sought erasure or acknowledgment? Why do you think that sometimes people need to be lost?

8. Your book grapples with ideas of what it means to be lost and what it means to be found. When in your life have you yearned for either, and have there been times when as a writer you’ve sought erasure or acknowledgment? Why do you think that sometimes people need to be lost?

Like many kids, I felt lost and unseen, partly due to the era when I grew up. Parents were not helicopters. I saw them in the morning and at night. I grew up in suburban Los Angeles, where it was possible to be even more invisible. It gave me a certain freedom, but also a sense that I was very tiny in an indifferent universe. We carry those experiences into whatever we do later.

Journalists can disappear while telling someone else’s story—at least we think we can. Of course, we always come into any story with our own beliefs and biases. At some point, I began to write essays and then fiction. It was harder to hide, although I still often yearn to do that.

“We need stories, and always have, to help us make sense of the world and the choices we face. There is a reason why people gathered together to hear stories before they had ways to record or print them. They were passed on from one person to another, showing us what it means to be human. We find ourselves in those stories.”

9. What is the most daring thing you’ve ever put into words? Have you ever written something you wish you could take back?

If you’re a journalist long enough, you’ll make mistakes—which you can admit and usually correct. Just about everything you commit to writing is daring. I learned early on that telling someone’s story is a serious responsibility.

During my first year as a reporter, I profiled a municipal judge who got my attention by ordering women to leave the courtroom when a defendant began swearing. I refused, so he told the man to substitute “bleep” for swear words. The judge found him guilty. His punishment: The man and his victim had to stand up and publicly shake hands. I spent many days in this courtroom taking notes.

Soon after the story appeared, someone sent me a copy of a secret state judicial investigation into the judge’s disparate treatment of those who appeared before him. I stayed up all night and wrote carefully, then felt terrible the next day when the judge showed up at the newspaper office, devastated. My editor said that he’d done the damage to himself, which was true. I wouldn’t take it back, but I never forgot how it felt to see that judge on his knees, asking why I’d ruined his life.

10. Why do you think people need stories?

We need stories, and always have, to help us make sense of the world and the choices we face. There is a reason why people gathered together to hear stories before they had ways to record or print them. They were passed on from one person to another, showing us what it means to be human. We find ourselves in those stories. We don’t always have answers, but we can read and listen to how others navigated life. With all we’re facing, we particularly need stories right now.

Katherine Seligman is a journalist and author who lives in San Francisco. She has been a writer at the San Francisco Chronicle Magazine, a reporter at the San Francisco Examiner, and a correspondent at USA Today. Her work has appeared in Redbook, LIFE, Money, California Magazine, the anthology Fresh Takes, and elsewhere. At the Edge of the Haight is her debut novel.