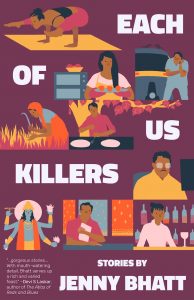

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Jared Jackson speaks with Jenny Bhatt, author of Each of Us Killers (7.13 Books, 2020).

1. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

1. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

My writing is rarely ever about stating a particular truth and mostly about exploring how different truths or realities might be from different perspectives. I’m trying to understand certain questions for myself that come up when I encounter a seemingly incontrovertible or universal truth. It’s that subversive child inside of me who began by questioning my mother’s bedtime stories to creating my own versions of them.

The best fiction doesn’t simply give us universal truths but raises uncomfortable questions about such truths. Fiction should always complicate things, contradict our regular biases, widen the lens, make us see different nuances of what we’ve accepted as “truth.” I hope that, when people read my fiction, that’s what they experience.

2. What is one book or piece of writing you love that readers might not know about?

I’m a huge fan of Vincent van Gogh’s letters. They’re filled with these questions about art, aspirations he had for his own works, and aesthetic and spiritual pleasures he experienced from the works of other artists. Despite the challenges throughout his life and his sad, mysterious death, I’m always filled with a kind of optimism when I read his letters. They remind me that it’s worth persevering no matter what may happen and in taking pleasure in the art-making process for itself. His Collected Letters would be my Desert Island book.

“The best fiction doesn’t simply give us universal truths but raises uncomfortable questions about such truths. Fiction should always complicate things, contradict our regular biases, widen the lens, make us see different nuances of what we’ve accepted as ‘truth.’ I hope that, when people read my fiction, that’s what they experience.”

3. How can writers affect resistance movements?

The most important thing writers can do is wield our words in ways that give people pause for thought, which means taking calculated risks. But what does that old chestnut mean today? When I think of taking risks with writing, I’m thinking of what Afrikaner author, André Brink, once wrote: “In an open society, in which the whole alphabet of human experience from A to Z is accessible to the writer and where the whole alphabet of expression from A to Z is at his disposal, the very extent of his freedom may diminish the weight of what he has to say. In the closed society, on the other hand, in which the writer is allowed only the freedom to pronounce the letters from A to M, his word immediately acquires a peculiar weight if he risks not only his comfort but his personal security in choosing to say N, or V, or Z. Because of the risk involved, his word acquires a new resonance: it ceases, in fact, to be merely a word and enters the world as an act in its own right.” We may like to believe that we live in an open society here in the United States. But, even here, within certain communities or due to certain sociocultural conditioning, we’re not free to write about certain things. Those are exactly the things we must write about. That’s risk-taking, that’s resisting.

4. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

I’ve just finished rereading Toni Morrison’s Jazz for a writing workshop I’m teaching. There have been so many amazing books out this year already. Next on my list is Meena Kandasamy’s Exquisite Cadavers, which comes out in the U.S. in November. It’s been out in India and the U.K. already. She’s done some interesting things, structurally, with the novel form there. And it’s a subversive response to those who kept calling her previous novel, When I Hit You, autobiographical. So, I’m very interested to read it for both of those reasons.

5. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity?”

Identity has always shaped my writing. I don’t shy away from it. I’m brown, female, middle-aged, immigrant, late-bloomer, Indian, Gujarati, American, South Asian, wife, sister, daughter. All of these make me the writer that I am. So, yes, there is such a thing as “the writer’s identity.” When I’m reading or reviewing a book, I want to first understand the writer’s intent, which is deeply connected to their identity. And identity is a fluid, evolving thing. My mother’s favorite Gujarati writer, Dhumketu, had a favorite saying that he often repeated in stories and essays. I’ll paraphrase: “The artist creates his artwork, but the artwork creates the artist.” Our multidimensional identities shape our writing, and the writing, in turn, further shapes our identities.

“Identity has always shaped my writing. I don’t shy away from it. I’m brown, female, middle-aged, immigrant, late-bloomer, Indian, Gujarati, American, South Asian, wife, sister, daughter. All of these make me the writer that I am. So, yes, there is such a thing as ‘the writer’s identity.’ . . . Our multidimensional identities shape our writing, and the writing, in turn, further shapes our identities.”

6. What advice do you have for young writers?

I wouldn’t be the writer that I am today without having lived a varied life before I committed to my writing full-time. This doesn’t mean that I’m a great writer. It just means I’ve got a deeper well to draw from. So, my advice for younger writers is to go live life a little first; get some other experiences first-hand; don’t be in a hurry to get published, win awards, etc. That is all.

7. Why do you think people need stories?

Because the human mind has a need to make sense of things. Because we’re wired for stories—even when we’re sleeping, our brains are making stories with dreams. Because we’re addicted to myths of all kinds. Because we’re fascinated by origins and endings, rise and fall, journeys and homecomings. Because stories help us discover other worlds, and through them, different versions of our own selves.

8. Your debut story collection, Each of Us Killers, features 15 stories that span the American Midwest, the U.K., and India. The collection’s first story, “Return to India,” focuses on an Indian American coworker’s murder through the interrogation of his former coworkers at a U.S. engineering firm. We learn about the murdered man only through their details, which reveal his coworkers’ prejudices and racial biases. The story also highlights the contemporary temperature of the country with sentences that evoke thoughts by our current president and ends with, “What has happened to America, can anyone tell me?” What made you want to make this the first story in the collection? How does it inform the reader, thematically or otherwise, about what will follow in the rest of the collection?

8. Your debut story collection, Each of Us Killers, features 15 stories that span the American Midwest, the U.K., and India. The collection’s first story, “Return to India,” focuses on an Indian American coworker’s murder through the interrogation of his former coworkers at a U.S. engineering firm. We learn about the murdered man only through their details, which reveal his coworkers’ prejudices and racial biases. The story also highlights the contemporary temperature of the country with sentences that evoke thoughts by our current president and ends with, “What has happened to America, can anyone tell me?” What made you want to make this the first story in the collection? How does it inform the reader, thematically or otherwise, about what will follow in the rest of the collection?

This story was influenced by the 2017 hate shooting of Srinivas Kuchibhotla, an Indian tech engineer in Olathe, Kansas. I was in India at the time and watched it unfold over news and social media with a horrified fascination. And I remember wondering whether the well-meaning white coworkers who were eulogizing him really understood his life (and that of many first-generation immigrants like him and me). It’s quite a long story to start a collection with, probably. But I thought it might set the stage for what the entire collection is about: how much the various intersecting aspects of our personal identities—nationality, race, ethnicity, class, gender, caste, etc.—shape our daily work interactions and, eventually, our entire working lives. Both the opening and the closing stories also have these multiple or collective points of view about a character who’s not a living actor in the story. I wanted to bookend the collection with this plurality of perspectives that explores crowd psychology and how we often end up, as groups or communities, telling ourselves these different stories about what has happened in our midst.

“I’ve come to see how every act of reading or writing is an act of translation. Reading involves translating and interpreting the writer’s meaning and intent. Writing involves interpreting and giving voice to our own thoughts, which are guided by the things we have read, seen, heard, and experienced. Those of us who translate other writers’ works do so because we want to dive deep and fully immerse ourselves in their words, language, and stories.”

9. You are the host of the podcast “DesiBooks,” a literary podcast that invites desi writers to read and discuss their art, and literature more broadly. For readers who might not know, who falls into the category of “desi?” What inspired you to create this specific podcast—this space—for desi writers?

Thank you for asking this question.

“Desi” applies to a person of South Asian descent who lives anywhere in the world. The official definition of South Asia contains the following countries: India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan, Afghanistan, and the Maldives. And, of course, their globally-scattered diaspora. The word is also often used as a qualifying adjective or adverb: “desi writer” or “desi cooking.” We discussed the ancient etymology of the word on episode two of “DesiBooks.”

While South Asian writers all over the world have been progressing more than ever, it’s still not easy to discover the gems out there because of uneven or negligible media coverage. Even within the respective South Asian countries. Beyond the handful of big names like Salman Rushdie or Arundhati Roy or Jhumpa Lahiri, South Asian literature has meant certain kinds of timeworn stereotypes and tropes—arranged marriage, slum life, terrorism, crooked politicians, immigrant assimilation. And, once the literary critics have hailed a couple of new South Asian writers as “the ones,” we stop hearing about any others. Particularly in a year like this, there’s even less oxygen for any desi literature that veers away from those stereotypes and tropes. Rather than complain about this, I thought, why not shine a light on some of these other kinds of desi books coming into the world? And thankfully, the podcast has gained some loyal listeners, gotten some good press, and I have plans to do more in the coming few months.

10. You are also a literary translator, with a book that will come out in December 2020 from HarperCollins India. Your collection is formally diverse, featuring different story structures that, to me, best execute your intentions as a writer for each story. Does translating literature make you think about your use of language in your own work? If so, in what ways has it influenced how you tell stories?

Thank you for saying that about the formal diversity of the collection. Yes, I was very intentional with how I used voice, point of view, and narrative structure in each story. Sometimes, that meant redoing a story entirely if something wasn’t working right.

I was a writer before I became a translator. But I’ve learned to appreciate linguistic, aesthetic, and cultural diversity more profoundly because of the translation work. I’ve also come to see how every act of reading or writing is an act of translation. Reading involves translating and interpreting the writer’s meaning and intent. Writing involves interpreting and giving voice to our own thoughts, which are guided by the things we have read, seen, heard, and experienced. Those of us who translate other writers’ works do so because we want to dive deep and fully immerse ourselves in their words, language, and stories. This is not unlike how, as readers and writers, we seek to inhabit the worlds of fictional characters.

Translation has also helped me discover parts of my own Gujarati and Indian culture and storytelling traditions that I wouldn’t have done otherwise—especially having lived in the West for so long. So, yes, all of those cultural nuances and storytelling traditions flow into my own fiction writing.

Thank you, Jared, for this opportunity to answer these thoughtful questions. Much appreciated.

Jenny Bhatt is a writer, literary translator, and literary critic. She is the host of the “DesiBooks” podcast. Her debut story collection, Each of Us Killers (7.13 Books, September 2020), was listed as a most anticipated book of 2020 by Electric Literature, The Millions, and Literary Hub. Her literary translation of Gujarati short story pioneer Dhumketu’s best short fiction will be out in late 2020. Her writing has appeared or is forthcoming in various venues including The Atlantic, NPR, BBC, The Washington Post, Literary Hub, Longreads, Poets & Writers, The Millions, Electric Literature, The Rumpus, Kenyon Review, PopMatters, Scroll.in, and more. Her fiction has been nominated for Pushcart Prizes and The Best American Short Stories 2017. She was a finalist for the 2017 Best of the Net Anthology. Having lived and worked her way around India, England, Germany, Scotland, and various parts of the United States, she now lives in a suburb of Dallas, Texas.