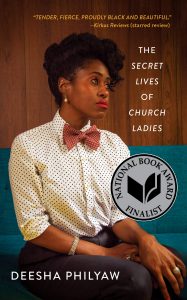

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Jared Jackson speaks with Deesha Philyaw, author of The Secret Lives of Church Ladies (West Virginia University Press, 2020).

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

The very, very first was a picture book, There’s a Monster at the End of this Book. I discovered how a book can draw you in, how a character can speak directly to you. A later book was Daddy Was a Number Runner by Louise Meriwether, a coming-of-age YA novel about a Black girl living in Harlem in the 1930s. That was the first time I saw myself in a book. Even though I was separated from the main character in terms of time and place, I discovered that books could take me places and make my world larger than what was outside my front door.

2. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

A lot of my fiction is rooted in nostalgia and longing for the people and culture of my childhood in the South, particularly the older women and the girls I grew up among. They live in my memory and my imagination. At the same time, the impetus for much of my fiction has been a kernel of my own dissatisfaction. So early on, because I didn’t feel that I could write freely about my dissatisfaction, I gave that kernel to my characters who were inspired by the women and girls of my youth. My fiction is my attempt to tell the truth about my life and the lives of women and girls who look like me, who struggle to get free of the same things I’ve struggled to free myself from, who seek after our own pleasure and satisfaction in a world that tells us we should be content with something less—something different than what we long for.

“My fiction is my attempt to tell the truth about my life and the lives of women and girls who look like me, who struggle to get free of the same things I’ve struggled to free myself from, who seek after our own pleasure and satisfaction in a world that tells us we should be content with something less—something different than what we long for.”

3. How can writers affect resistance movements?

Teju Cole said it best: “Writing as writing. Writing as rioting. Writing as righting. On the best days, all three.” Writers speak truth to power. Writers disrupt white supremacist narratives with truer, more just narratives. Tenderness, joy, humor, and imagination are among our weapons of resistance. I once heard an evangelical pastor on a radio show warn Christian parents that they should not allow their kids to read the popular picture book Where the Wild Things Are. According to the pastor, the book’s main character thwarts his parents’ attempt to punish him by escaping into his imagination and having a grand adventure, after being sent to his room. Imagination is a tunnel to freedom that terrifies those most invested in keeping people enslaved, marginalized, or obedient.

4. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

I’m enjoying The Office of Historical Corrections by Danielle Evans and The Final Revival of Opal & Nev by Dawnie Walton. Next up: Black Futures by Jenna Wortham and Kimberly Drew.

5. What is the most daring thing you’ve ever put into words? Have you ever written something you wish you could take back?

I wrote an essay about my challenging relationship with my mother, titled “How Can You Be Mad at Someone Who’s Dying of Cancer?” Under the best circumstances, it takes courage to write about mothers as less than perfect, as people, without completely demonizing them. Add cancer to the mix, and it’s terrifying. It also took a lot of nerve for me to write about my father, who was no one’s definition of a good father. I carried a lot of shame about that reality, even though his behavior was certainly not my fault. I felt very exposed in that essay. But I don’t wish to take back either of those essays. I do wish I had not written so much about my children, back in my blogging days. I was not respectful of their privacy, and they could not give consent.

“Writers speak truth to power. Writers disrupt white supremacist narratives with truer, more just narratives. Tenderness, joy, humor, and imagination are among our weapons of resistance.”

6. What advice do you have for writers?

Other than “respect your children’s privacy,” if you have children, I will share the best advice given to me as an aspiring writer who was super hungry to be published in order to be validated as a “real” writer: Don’t worry so much about getting your writing published. Worry about getting better at writing. Instead of looking for people to tell you your writing is good, embrace revision, embrace critique from good people who can tell you how to make your writing good, and how to make your good writing even better.

7. Which writers working today are you most excited by?

So many! But I will name a few, in addition to the writers I mentioned above: Kiese Laymon, Tamara Winfrey Harris, Yona Harvey, Brian Broome, Samantha Irby, Dennis Norris II, Damon Young, Renee Simms, Tyrese Coleman, Bassey Ikpi, Nafissa Thompson-Spires, Sarah M. Broom, Robert Jones Jr., Sejal Shah, Kelli Jo Ford, Megha Majumdar, Rion Amilcar Scott, and Maurice Carlos Ruffin.

8. The narratives in your story collection are full of ideas, language, and situations particular to your subject matter: Black women and girls. Can you speak to the importance of representing these voices and perspectives? What truths and myths did you want to examine as you shaped your book?

8. The narratives in your story collection are full of ideas, language, and situations particular to your subject matter: Black women and girls. Can you speak to the importance of representing these voices and perspectives? What truths and myths did you want to examine as you shaped your book?

We know that false narratives about Africans were used to justify chattel slavery in the United States and elsewhere. Africans were deemed bestial, subhuman; African women were considered hypersexual, unrapeable. These narratives attempted to obscure the atrocities of slavery. After Emancipation, the lying about Black folks continued—and continues—as a way to justify white terrorism and white violence, racial discrimination, and disenfranchisement. So for me, telling the truth about who Black women and girls are and centering us in the narratives of our own lives, is paramount. In particular, I wanted to challenge the idea that others—be it our families, the church, or the larger culture—should be allowed to dictate what is enough for us, what should satisfy us. I wanted to explore what happens when Black women and girls push back against confinement and binaries, against the expectations and burdens others place on us. I wanted to tell the stories and secrets that we tell each other and ourselves, when the only gaze is ours.

“For me, telling the truth about who Black women and girls are and centering us in the narratives of our own lives, is paramount. In particular, I wanted to challenge the idea that others—be it our families, the church, or the larger culture—should be allowed to dictate what is enough for us, what should satisfy us. I wanted to explore what happens when Black women and girls push back against confinement and binaries, against the expectations and burdens others place on us.”

9. In the book’s first story, “Eula,” the narrator, Carlotta, says to her best friend and annual lover, “You’re not who you thought you were either.” This feels like a theme throughout the book: characters wrestling with desires, secrets, and external and internal pressures. Some succumb to them, while others rise above them. Did you have a guiding central question as you put together your collection—a north star, if you will? If so, what was it, and when did you realize it?

Yes, I didn’t realize until after the fact, after the collection was completed, that each of the stories considers: What happens when we try to get ourselves free, in large and small ways, in private or right out loud?

10. Too often in popular culture and society, Black women and girls are oversexualized. Your collection features Black women and girls who have full and layered sexual lives, and who speak freely about them. There are characters who learn to be comfortable in their physical bodies, who dictate the terms of their sexual relationships, and who seek their own sort of justice when lines are crossed. How did you set out on empowering these characters through sex? What were your concerns while writing these stories and the decisions each character makes?

I don’t know that they are empowered through sex as much as they are more generally seeking to have agency and live honestly and freely. But because the church is so obsessed with women’s sex lives and sexuality, and because women are often reduced to our sex, sex becomes the default battleground for much of this struggle for agency and freedom. I wasn’t concerned about the characters being read as oversexualized, as stereotypes, because I can’t worry about folks who aren’t going to read in good faith. I knew that some readers would frown on the choices some of the characters make, and that’s fine. It’s important that Black women—real and fictional—be allowed our full spectrum of humanity. Because the binary that says we must be either hypersexual sinners or chaste saints needs to die.

Deesha Philyaw’s debut short story collection, The Secret Lives of Church Ladies, was a finalist for the 2020 National Book Award for Fiction. The Secret Lives of Church Ladies focuses on Black women, sex, and the Black church. Philyaw is also the coauthor of Co-Parenting 101: Helping Your Kids Thrive in Two Households After Divorce, written in collaboration with her ex-husband. Her work has been listed as a Notable Mention in the Best American Essays series, and her writing on race, parenting, gender, and culture has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, McSweeney’s, The Rumpus, Brevity, Dead Housekeeping, Apogee Journal, Catapult, Harvard Review, ESPN’s The Undefeated, Baltimore Review, TueNight, Ebony and Bitch magazines, and various anthologies. Philyaw is a Kimbilio Fiction Fellow and a past Pushcart Prize nominee for essay writing in Full Grown People.