The PEN Ten: An Interview with Diana Marie Delgado

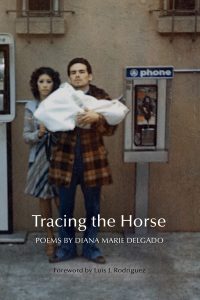

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, PEN America Prison and Justice Writing Program Director Caits Meissner speaks with Diana Marie Delgado, author of Tracing the Horse (BOA Editions, 2019).

Photo by Fletcher and Co

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

I grew up at the La Puente Library in the San Gabriel Valley of Southern California. By the time I was nine years old, I had read everything in the children’s section, and I began checking out romance novels and books that I shouldn’t have been reading: Sybil and Helter Skelter. I would say that I was impacted most by fairytales, romance novels, and horror; I don’t think my taste has changed that much.

2. There are many poems in Tracing the Horse that function like photographic snapshots, and do a great deal of work in scene and location-setting, while also allowing room for mystery, evoking an uneasy sense of danger/fear. They remind me, in a way, of Gregory Crewdson’s work. Crewdson is known for highly staged, evocative, film-like photographs that, as he says, “feel ordinary and yet tinged with a sort of certain kind of beauty and terror.” Can you talk about these shorter poems in the book? How did you think about the sequencing of them, and from a craft perspective, why you choose this approach?

I thought a lot about craft. I knew the story, but through craft, I knew I could capture the unseen. I referenced the dread I’d felt in Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Paramo and Carlos Fuentes’ Aura, and imagined a dream-like environment. At the same time, the material had to be grounded, and I did that with the intimacy created by the speaker, who is vulnerable and recounts a harrowing period in her life.

Thanks for noticing the sequencing! I reworked it for years, and if given the chance, would still rework it! I think of Tracing the Horse as a constellation, and the shorter poems as tiny stars. When I moved away from an idea of order and thought more about shape, I was able to order the poems around to give the greatest effect.

“I think that the writer can ‘write’ themselves free.”

3. Men populate the book, and the poems’ speaker(s) are often positioned in relationship to the problematic behavior of men—family members and lovers, primarily. The book description says the poems “ask the reader to consider reclamation and the power of the self,” which makes me think about your poem, “Who Makes Love to Us After We Die.” In that poem, you write, “The best movies begin with an encounter and end with someone being set free.” I’m curious about putting the book in this context you frame for film: Can the writer write herself free? If so, what does that mean, and if not, why not? What can poetry offer toward liberation/reclamation, and perhaps, where are its limits?

I think that the writer can “write” themselves free. One can create a counternarrative, and perhaps that’s where I hope, in this poem, and opine that it can “end with someone setting someone free.” I do keep the writer separate from the self, and even the other self that performs in my day-to-day. What I mean is that after the book is finished, you still confront what has happened in both the body and the mind, and that is something that book publication does not release you from. That’s to say that Tracing the Horse was an attempt to “set myself free,” but as I say in another poem, “Men are the only islands/ I’ve ever lived on. / I’ll never get away.”

4. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

This is a great question because there is no answer! The minute I give an answer, that answer is no longer true. What I can say is that I told a truth in my book, and that I used aspects of fiction not traditionally used in poetry to tell the “story” of that truth.

“Writers can help move conversations in directions that are challenging but ultimately necessary, and we can do it in ways that present the issues to a wide audience, bringing about greater healing.”

5. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

My creative process is an avalanche, and then a meticulous revision process that brings out my obsessive-compulsive side. I stay with my poems for a very long time before I publish, and it’s honestly not me thinking they are precious, but wanting to tease out the most potential. I’ve spoken about this in other places, but I can write 20 pages easily. Out of those 20 pages, I only keep a line or two, a scene.

6. What is one book or piece of writing you love that readers might not know about?

Migdalia’s Cruz’s amazing one-act play, Telling Tales. The play is 11 monologues about growing up Puerto Rican in the Bronx, and can be read—as I often have—as vignettes or even prose poems. It’s a piece of writing that showcases the power of voice and Cruz’s fearlessness in tackling difficult subject matter. It’s a must read.

7. I want to ask you about the devil, who lurks all over this book as both a threat—and almost, at times, strangely—a friend. The devil is a kind of trickster in this way. We think of the devil as being summoned by personal sins—“My aunt handed me an organdy/fan and said: Hold this if you’re frightened / or want to lose yourself—the Devil / can dance like a goddamn dream”—but is the devil actually the larger cultural violences you address in these poems (addiction, incarceration, racism, and classism)? Can you share some insight about the devil’s shapeshifting persona in this text?

7. I want to ask you about the devil, who lurks all over this book as both a threat—and almost, at times, strangely—a friend. The devil is a kind of trickster in this way. We think of the devil as being summoned by personal sins—“My aunt handed me an organdy/fan and said: Hold this if you’re frightened / or want to lose yourself—the Devil / can dance like a goddamn dream”—but is the devil actually the larger cultural violences you address in these poems (addiction, incarceration, racism, and classism)? Can you share some insight about the devil’s shapeshifting persona in this text?

The devil is all of the above. But he is firstly, at least for me, a beautiful man. That’s how my grandparents described him, hermoso. And that detail, that his beauty is bewildering, has always confused and fascinated me. Especially because family lore is that an uncle met him.

In the context of the book, the devil’s duplicity can be seen as these larger issues in the world, but I think I’d be safer in saying that he is more of an imago, who both wounds—and helps heal—that wound.

8. How can writers affect resistance movements?

There are many ways a writer can affect resistance movements, but the way that I find I’m most responsive to that call, is through voice. I’m especially interested in writers like Claudia Rankine who shed light on racism, sexism, and classism. These are issues that affect people of color in their day-to-day, but often go unchallenged due to the nuanced ways these situations play out and us not having the words, but carrying that feeling that something wrong just happened, inside us.

This is especially important for individuals who see themselves as allies. There is a lot more work to do in those circles, with individuals who see themselves as “woke,” but who oftentimes, feel that if they are friends with people of color, they are part of the movement—when in fact, they are often part of a larger, more insidious problem. Writers can help move conversations in directions that are challenging but ultimately necessary, and we can do it in ways that present the issues to a wide audience, bringing about greater healing.

“I think the best writing is where the writer makes the reader uncomfortable, maybe even worried. But the wish to take it back—never.”

9. What is the most daring thing you’ve ever put into words? Have you ever written something you wish you could take back?

I’m the eldest daughter in a first-generation Mexican-American household, who was raised Catholic, so anything that I make public is daring!

I’ve never wished to take anything back. I think the best writing is where the writer makes the reader uncomfortable, maybe even worried. But the wish to take it back—never.

10. Which writer, living or dead, would you most like to meet? What would you like to discuss?

I’d most like to meet the Chilean writer, Roberto Bolaño. His books are messy, sad, operatic, punk-rock, and inimitable. One of my favorite passages in a book is from his book, Amulet. Here’s the translation to English: “I thought, the two things are connected, writing and destroying, hiding and being found.”

I’d love to talk with him, over a drink, about his unfinished masterpiece, 2666.

Diana Marie Delgado is the author of Tracing the Horse, a New York Times “New & Noteworthy” selection, and the chapbook Late Night Talks with Men I Think I Trust. She is the recipient of numerous grants, including a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. A graduate of Columbia University, she currently resides in Tucson, where she is the literary director of the poetry center at the University of Arizona.