The medical system is no one’s friend. But for far too long, women have disproportionately suffered under its labyrinthine processes, lack of research, and having their pain and issues fall on deaf ears.

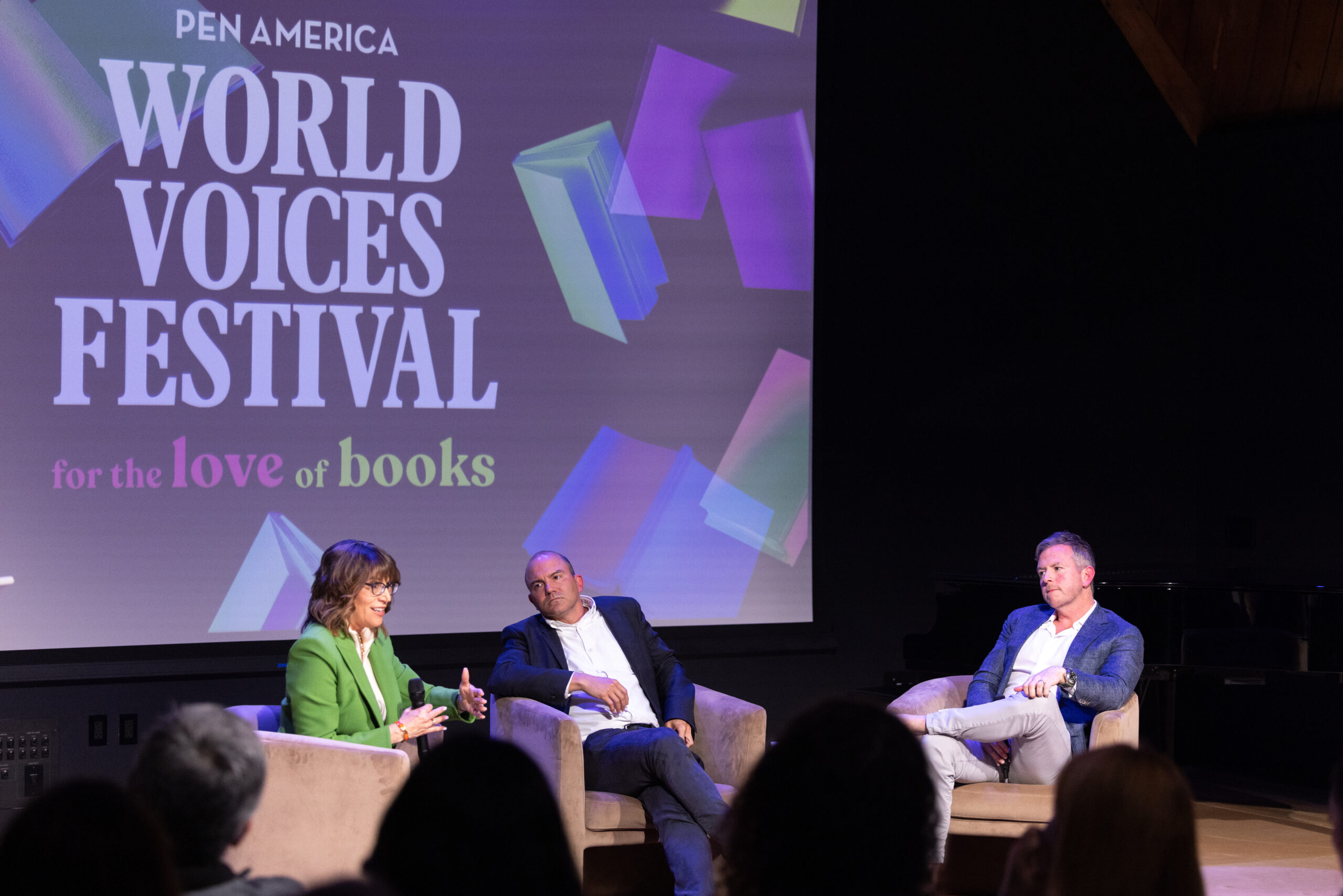

In a panel moderated by Tanya Selvaratnam (Assume Nothing: A Story of Intimate Violence), Samina Ali (Pieces You’ll Never Get Back) and Ariel Gore (Rehearsals for Dying: Digressions on Love and Cancer) discussed their memoirs, which chronicle the ways the medical system failed them.

Ali, in a stunning journey spanning two decades, recovered from severe brain-damage following childbirth that had left her without recognition of herself, her family, language, and mobility. Gore’s memoir is an account of living with her wife’s metastatic breast cancer from her diagnosis to her inevitable passing. At the 2025 World Voices Festival, in the panel titled, “Seen, Heard, and Believed? Exploring Women’s Experiences in Healthcare,” the writers recounted their experiences with various medical institutions, finding resilience in the darkest times, and continuing to lead with light and hope despite it all.

To tell their stories and raise awareness

Writing their respective stories was a way to cope with their unique situations — for Ali, recovering from something that no one believed she could, and for Gore, supporting a partner who constantly felt infantilized by the system around her. Their books serve not just as records but also alarm bells to the ways of the medical institutions in the United States.

Ali: “I remember thinking, for nine months I kept telling these doctors, there’s something wrong, and for nine months, they kept saying there’s nothing wrong. To the point where by the time I got to the delivery, they thought that I was hysterical, which led to them dismissing me and and then I thought, and now they’re telling me that I’m never going to write again.

“The U.S. is actually the only developed nation in the world where maternal mortality and maternal morbidity are on the rise. What I wanted to do in the book was show how the puzzle pieces were scattered, which is the analogy that the neurologist used. I wanted people to understand what it feels like, because I think that right now, especially, there is such a sense in the U.S. that things are really broken around us. We feel like things are breaking and we don’t know what to do with it, and all of our understanding of who we are and what we are, it’s gone. That’s exactly what I went through. And how do we then bear the unbearable? How do we survive when it seems like survival is impossible? How do we keep moving on? So those are the questions that the book answers.”

Gore: “The vast majority of people who get diagnosed with breast cancer are female-identified, and so everything that is wrong with the breast cancer industry is misogyny—on every level, everything is feminized. She presented like an old-fashioned butch lesbian with big tits, and she would intentionally wear pink to the appointment so that they would not give her the handout for prostate cancer. She would get these like certificates that were pink and look like she just did something special in preschool. Very few adult women want that.

“In my lifetime, billions of dollars have been spent on breast cancer awareness and so how come, when Deena was diagnosed, and her mother had died of breast cancer, we had no idea what to expect? Deena’s was metastatic on diagnosis, and really, almost all the information that we could find about breast cancer was geared towards people with earlier stage breast cancer and kind of ghettoized people with metastatic because it’s not good for fundraising, that this diagnosis is considered treatable, but incurable, considered universally terminal and and so it’s not good for fundraisers. So I interviewed a lot of people with earlier stages but still centered Deena’s story of having metastatic breast cancer to fix that. And at least in this project, have it be like we’re all in this together.”

I think that right now, especially, there is such a sense in the U.S. that things are really broken around us…And how do we then bear the unbearable? How do we survive when it seems like survival is impossible? How do we keep moving on? So those are the questions that the book answers.

Viewing the medical system’s fault lines that failed them

Both of their lives were irreparably changed from the moment they walked into the hospital. But as they took to paper to make sense of their devastating experiences, perspectives emerged, allowing them strength to share their stories.

Ali: “When a woman enters the hospital, it’s where two big stories collide. It’s the medical establishment. So they’ve got their experts, and they feel like they know everything. And as patients, we have to go in there and sort of surrender to what they know in order to proceed. And the second big story that comes in for women is that women grow up being taught to silence yourself. Don’t speak up. Don’t assert yourself. Don’t do this. Don’t do that. So when you’ve got, on the one hand, this powerful medical establishment saying, “I know what’s best for you,” and then you’ve got a woman entering that, going, “Okay, but I think there might be something wrong,” it’s like these two big systems collide, these two big stories collide. And that, I think, is where women get erased.”

Gore: “I just, I write. It helps me process what’s going on. It’s that constant feeling that you’re not being allowed to speak, and so we would come home from these appointments, and sort of act them out, as a stand up comedy routine, and then I would write it. And so it was a way to get a little bit of our agency back and feel like we have a voice in the system. We certainly don’t have any control over the trajectory of this disease. But our storytelling became a place where we could make a narrative arc out of anything, even if it’s total chaos. So that became a strength, just like, scrappy, ‘I’m gonna make a story out of this, and at least my friends are going to read it. You are so busted.’”

When a woman enters the hospital, it’s where two big stories collide. It’s the medical establishment. So they’ve got their experts, and they feel like they know everything. And as patients, we have to go in there and sort of surrender to what they know in order to proceed. And the second big story that comes in for women is that women grow up being taught to silence yourself.

Changing how you look at being alive

Ali: “I’m no longer scared of death. And I will say that there are worse things than death. So the part of my brain that they did not think I would ever get back are what they call the higher-order functions. The higher-order functions are the functions that make us human. They’re the functions that we use to imagine, to plan, to think about the future, to project ourselves into the future. So I couldn’t say, ‘Oh, this is what I’m going to do tomorrow, because I couldn’t imagine it tomorrow.’ So for me, that place where I lived for so many years was such a dark space that it is in many ways worse than death because you don’t have access to your thinking and your processing, and you don’t have access to be in connection to another human being.

“I’m hoping that one of the messages of the book is that by the end, you do see that it is a positive story and it’s a reminder of our strength, a reminder of what the body is capable of doing. It is capable of healing, is capable of rising above the struggles that life is full of. … My brain literally was, was disconnected, and in that disconnection, I lost connection with humanity. When I put the brain back together and connected it again, that was my reconnection with humanity, including my son.”

Gore: “I wish I could say that I grieve every day. I can’t believe it. I just really appreciate my time. But I feel like I’m just as grumpy as I’ve always been. I’m just as wasteful of my time as I’ve always been, but have more anxiety, I guess.

“When Dina got cancer, a lot of people would say to her, ‘I can’t imagine what you’re going through.’ And certainly after she died, people say that to me. What people are trying to do is put a space between themselves and something that they hope doesn’t happen to them anytime soon. I wanted it to not only create a thing where it’s like, yes, you can imagine. … We are all mortal. We are all going to die. In these political times, like Audre Lorde says, it becomes less and less important whether you’re unafraid and that you’re going to be with this culture in denial of death, that you will on some level accept it, and it doesn’t matter if you’re afraid.”

Want more?

Check out the panelists’ books:

- Pieces You’ll Never Get Back by Samina Ali

- Rehearsals for Dying: Digressions on Love and Cancer by Ariel Gore

- Assume Nothing: A Story of Intimate Violence by Tanya Selvaratnam