The 2023 Manifesto on Literary Translation

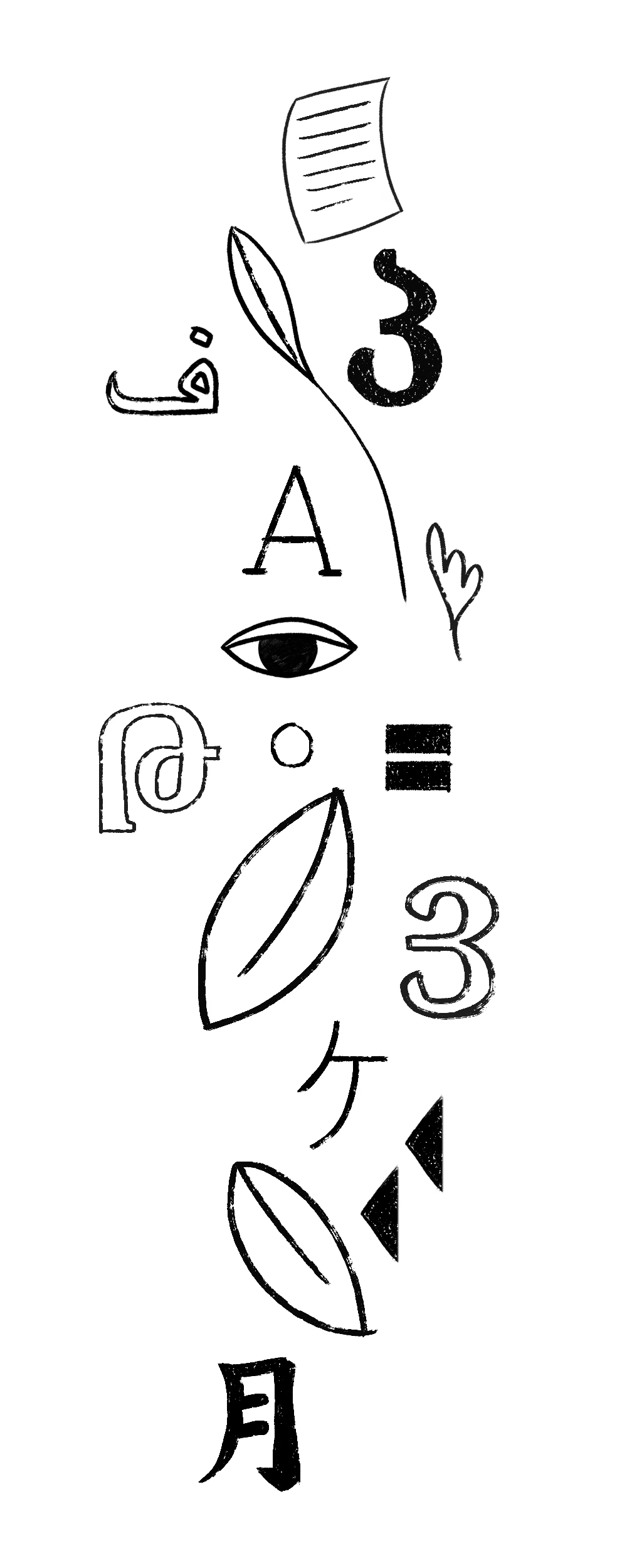

Introduction

Founded in 1959, the PEN America Translation Committee advocates on behalf of literary translators, working to foster a wider understanding of their art and offering professional resources for translators, publishers, critics, and others with an interest in international literature and ideas. The committee is proud to present this Manifesto on Translation to the literary translation community and to readers at large. The earliest version of a manifesto was penned in 1963 and signed by Robert Payne, who would later serve as chair of the translation committee as well as chair of the 1970 World of Translation conference, the 50th anniversary of which was commemorated by the 2020 Translating the Future conference hosted by Esther Allen and Allison Markin Powell. As part of the preparations for that event, a group of translators from the translation committee and beyond began drafting an update to the eight-page pamphlet, Manifesto on Translation, published in 1969. It took longer than expected to produce a collectively authored document that reflected what the group deemed to be an accurate accounting of the current state of translation affairs and an amply urgent and visionary call for the future of literary translation. But we hope that the 2023 Manifesto on Translation was worth waiting for, and that it will galvanize and inspire the various stakeholders that make up the translation community to deliberate and work together toward the goals enumerated within.

Allison Markin Powell, PEN America Board Trustee representing the Translation Committee

Annelise Finegan, Translation Committee cochair

Frieda Afary, Translation Committee cochair

Preface

In 1969, the PEN America Translation Committee produced a manifesto that opened with a call for action in advance of the 1970 “World of Translation” Conference, billed as the first international conference on literary translation held in the United States. The call for action reflected the drafters’ view of the state of translation at that time, focusing on the rights of the translator in the context of the publishing industry and translation studies in the academy. The manifesto called for raising the status of the translator, expanding the role of translation studies in the U.S., engaging publishers, and building translation resources. In 2020, the 50th Anniversary Conference “Translating the Future” reflected on how literary translation has changed since 1970 and invited a collective, international envisioning of what it may become over the next half century. In conjunction with the conference, a group of U.S.-based translators has drafted a new manifesto to address the art of literary translation in the twenty-first century, to renew and recalibrate calls for change in light of how the field has evolved, and to articulate what we want to see shift in the future.

Call to Action

We understand translation to be a creative art in its own right, even as it continues to be regarded as marginal and derivative by many in the greater literary community. In the more than fifty years since the PEN Translation Committee published its manifesto, we have taken meaningful steps toward legitimizing translation and the work of translators. National and international institutional structures have been established to recognize the cultural value of translation, while translation studies has emerged as a discipline that has opened up innovative ways of theorizing and practicing translation today.

Despite these advances and an increase in attention paid to translators in recent decades, the broader public and the publishing industry still misconstrue, obscure, and undervalue translation. In 2023, translators remain underpaid, often absent from book covers, and regarded as adjuncts to literary production. Most publishers do not prioritize the promotion of texts in translation, thus perpetuating an underperforming cycle of comparatively low print runs and sales along with the narrow readership that follows. Translators must continue to push for infrastructural change so that this crucial intellectual and artistic work is financially viable. We must also be vigilant about how we influence U.S. attitudes toward translation and non-Anglophone cultures through our work, as well as how we represent our work in public life.

We call for translation to be understood as a specialized form of writing. The lack of this acknowledgment has led not only to erasure of the translator’s labor, but also to a suppression of the social and political nature of the translator’s cultural work. In writing a translation, the translator establishes a set of interpretive relations with an existing text. The translator’s choices—including text selection—are inextricable from a given social and historical moment, and the translator’s aesthetic and ethical sensibilities shape the translated text for a new literary context, paving the way for dynamic and varied readings. To resort to notions of translation as purely mechanical reproduction or as “capturing” or being “faithful” to some aspect of the “original” eliminates the consideration of this cultural practice, thus reducing its artistic and intellectual possibilities—and also, necessarily, political ones—by attempting to confine the result to a single meaning. When seen as a particular kind of writing, translation emphasizes the myriad interpretations available and has the potential to combat the tendency to essentialize cultures and languages.

Translation plays a role in the globalization of everything from forms of artistic expression to laws, scientific knowledge, and politics, and it frames how readers in the U.S., including those who are multilingual, engage with other languages and cultures. As U.S.-based translators, we must recognize that we are positioned to resist or to perpetuate neoliberal globalization and its attendant forms of cultural imperialism, which have intensified asymmetrical relations among nations, peoples, cultures, and languages. Contending with the ethics of our translation work by acknowledging it as geopolitically charged presents an opportunity to intervene in U.S. cultural imperialism in particular. In the political and economic moment when this is being written—one in which the COVID-19 pandemic has further foregrounded our planetary interconnectedness as it has escalated the social inequities already deeply entrenched and heavily policed through hierarchies of race, gender, class, nation, citizenship, language, and culture—we are compelled to reassert a long-standing demand for a paradigm shift.

Every act of translation intervenes in the current geopolitical economy. With each one, a translator has the potential to actively contest and destabilize the damaging portrayals that sustain the forms of structural violence and exploitation that further entrench existing asymmetries. It is imperative not only that translations account for a larger percentage of U.S. cultural production but also that they be conscientiously situated within global frameworks and resist these portrayals. The new iterations of literary works that translators create through their interpretative labor may prompt readers to reconsider their assumptions and understandings of languages and cultures. Through this labor, translators have been (and a greater number of us should strive to be) advocates and change agents for more democratic forms of globalization, ones responsive to the overlapping histories of empire, settler colonialism, the trans-Atlantic slave trade, and white supremacy in the U.S. and beyond its borders, all of which translation has also been used to facilitate.

We announce this call for action in the belief that translation nonetheless has transformative global potential. More of us should join the translators who have been acknowledging and working against historical injustices and their ongoing legacies, to ensure that translation communities in the U.S. play a meaningful role in counteracting disparities in power and prestige among the world’s languages and peoples. We ought to approach our work in full awareness of the responsibility we bear given the history and geopolitical positioning of the U.S. and the global hegemony of English. We must resist flattening the gamut of human experiences by rendering them according to an inward-looking U.S.-Anglophone worldview. We call for the entire literary community to move forward with a critical approach that recognizes translation as the engaged, collaborative, and creative writing practice that it is.

Translation is a form of writing.

- We call on everyone who engages with translation to acknowledge it as a creative art in its own right, one that produces new work by negotiating between at least two socio-cultural and linguistic contexts.

- Translation must be understood as a specialized form of writing, which requires drawing on the translator’s own aesthetic sensibilities and interpretations.

Translation must be sustainable as a livelihood.

- We call on publishers, institutions, and translation organizations to recognize translation as a highly skilled form of artistic labor and to remunerate it accordingly, in a manner that makes translation financially viable as a profession.

- We call on publishers, institutions, and translation organizations to grant translators their legal and moral rights as creators of a new text in another language. Noting the framework of intellectual property law in the U.S., translators must receive copyright over their work, as well as continuing rights in the form of royalties and subsidiary rights while the translated text remains in print.

Translators have responsibilities.

- We call on translators to educate themselves and others to understand the cultural, social, racial, political, and linguistic contexts in which they work, and how translation can impact asymmetrical power relations. We challenge the tendency to assimilate texts from distinct cultural and historical contexts into a universalizing account of human experience.

- We call on translators to make their labor and expertise visible by the means available to them and to the extent that they are comfortable doing so.

- We call on translators to act as members of a broad and interconnected community; to treat our fellow translators and their work with dignity; to couch our debates and critiques of one another’s work in respect; to lift each other up professionally; to support those who have been subject to intimidation, harassment, and blacklisting within our field; and to work collectively to ensure fair treatment and compensation for all translators.

- We call on translators to be transparent about rates and terms, to not undercut colleagues in the field, and to engage in open conversations about unpaid work. Following such practices would benefit the community at large, just as not doing so has a detrimental effect on the profession of literary translators as a whole, especially those who rely on translation as their primary source of income.

Authors have responsibilities.

- We call on authors to recognize and acknowledge translators as creative partners.

- As partners, we call on authors to advocate within the literary community for translators to have a stake in and share the success of the author’s work in translation.

Publishers have responsibilities.

- We call on the U.S. publishing industry to radically alter its relationship with translators, treating them not as ancillaries to literary production, but as authors in their own right and as collaborators who should be supported, respected, nurtured, and enlisted at all stages of the process of publishing literature in translation.

- We call on publishers to invest in and publish more translators and writers of color and women, as well as queer, trans, nonbinary, genderqueer, D/deaf, disabled, and neurodivergent translators and writers.

- We call on publishers to invest in and publish more literature from languages that remain underrepresented in English translation.

- We call on publishers to critically examine cultural erasure and the fetishization of difference in regard to texts in translation.

- We call on publishers to recognize the work of translators by always prominently displaying the names of translators on the front cover.

- We call on publishers to always give the translator the copyright to the translation they have created and to always give the translator the right to continuing royalties as long as their translation is in print.

- We call on publishers to increase the visibility of translators by promoting their work and creating readings and public literary events that center the practice of translation and translators.

- We call on literary publications that pay authors to also pay translators for their work.

- We call on all leading literary journals and prizes to be open to the submission of translated texts.

Institutions have responsibilities.

- We call on professional organizations involved in translation to take actionable steps toward building a diverse national membership, such as by mentoring emerging translators of color and queer, trans, nonbinary, genderqueer, D/deaf, disabled, and neurodivergent translators, and centering these translators in event programming.

- In 2023, the practice of literary translation remains marginalized in the academy. We call on universities to abandon this prejudice by ceasing to undervalue literary translation as a form of rigorous scholarship and creative endeavor and to give more weight to translation in hiring and tenure and promotion cases.

- We call on universities to make training in the production and study of translations integral to any undergraduate or graduate discipline that depends on texts in translation for its teaching and research.

Book section editors and reviewers of translations have responsibilities.

- We call on reviewers to always name the translator of a translated work in their reviews.

- We call on book section editors to recognize the responsibility they have to promote informed discussion about books from not only a wide range of languages, countries, and literary traditions, but also a more diverse range of authors, translators, and presses. If there is no one on an editorial staff who can effectively engage with a work in translation—either linguistically or culturally—effort should be made to find a freelance reviewer or scholar who can do this work. A translation should not be excluded from review coverage simply because an editor does not speak or read the source language.

- We call on book sections and publications that pay authors to also pay reviewers for their work, particularly when specialized knowledge of a language or literature is required to provide nuanced critical coverage.

- We call on professional reviewers, even those who do not speak a language other than English, to be advocates for literature in translation by developing regional and/or language-based specializations. These specialist reviewers play a crucial role in both broadening the spectrum of literary reviews and underscoring the sociohistorical and aesthetic contexts out of which translations emerge.

- We call on reviewers of translations to be attentive to a translator’s agency. Translators make use of specific lexicons, literary styles, genres, registers, and cultural terms in the creation of a literary text. Understanding how these linguistic and cultural resources have been utilized is essential to understanding how a translation fits into the wider literary landscape

Teachers have responsibilities.

- We call on teachers who use translated works of literature in their classroom to present them to students as translations.

- We call on teachers to recognize translators whose work is read and studied and to provide and discuss information about them and their translation method, whenever possible.

- We call on teachers to discuss with students the qualitative differences between and among multiple translations of a text and to note why a particular translation has been chosen over others, especially if only one is used in the classroom.

- We call on teachers to provide students with guidance on how to read, analyze, and evaluate a translation.

- We call on teachers to present translation to students as a scholarly discipline with its own history, including translation scholarship from non-Western traditions.

- We call on teachers to invite students—especially students who are multilingual, heritage-language speakers, or from other backgrounds underrepresented in the U.S. translation community—to envision themselves as future translators. We particularly encourage teachers to mentor these students.

Readers have responsibilities.

- We call on readers to actively seek to read works in translation and to read them as translations.

- We call on readers to engage with those works and to consider themselves part of the literary translation community by, for example, requesting libraries and bookstores to carry works in translation; requesting that libraries, bookstores, and cultural centers include translators in literary events; or providing comments on the translated works they have read on bookseller websites and other online venues.

Our vision for a responsible, inclusive literary translation community is one in which each member recognizes and is recognized for their contribution to the greater whole. The following sections address areas we have identified in 2023 as being in critical need of change and development.

Race and Racism in Literary Translation in the U.S.

The relative paucity of conversations about race and racism in the field of translation is alarming, but perhaps not surprising, given the way translators of color have historically been excluded from the field. We echo the call by translators of color for an end to silence concerning racialized exclusion within the translation community. The United States not only produces a large amount of literature for world consumption and funds little work in translation, but it also maintains unequal access to resources, education, and institutions through structural racism. There has yet to be a full reckoning with the role played by translators—including literary translators—in genocide, colonization, and enslavement, all of which continue to influence how the field operates today. As translators working within this cultural context, our work must be informed by rigorous discussions about how race and racism function in the field; we must challenge the status quo regarding institutional and cultural biases that perpetuate racism in all its forms. Concrete action must be taken in terms of who has access to the profession, how race and racialized language are translated, and how the work of authors and translators of color is disseminated and received.

Translators of Color

The majority of U.S. translators are white, the existing translation organizations are majority white-led, and efforts to diversify the field have largely relied on exploiting the intellectual and creative labor of people of color. These conditions exist both as the effects of historical racism in the field and also as the causes of current and ongoing barriers to access for translators of color. Given the complex ways that race intersects with economic precarity, any moves towards a true dismantling of structural racism must be material. Discussions about racism in the field and how translators are positioned within these racialized and racializing structures are only a first step toward concrete action. We must make changes within the infrastructure that supports translation:

- The range of spaces in which conversations about race in the field are held should be expanded beyond traditional institutions (e.g., within academia, major translation organizations, the translation publishing industry) to include kitchen-table and grassroots spaces, such as domestic/home spaces and community-oriented public spaces.

- Publishers should avoid asking for unpaid labor from translators of color, especially if it is in service of “diversifying” their catalog or masthead. Given barriers to institutional knowledge, publishers also have the responsibility to be more transparent regarding their missions, mastheads, salaries, payments, royalties, contracts, and timelines, so that translators do not bear the burden of guessing or asking about practices that might be exclusionary for translators of color.

- Institutions (publishers, organizations, universities, etc.) have the responsibility to raise—and, if necessary, divert—funds to hire more people of color; raise salaries and rates to increase access for people without generational wealth; create endowments for degree programs, internships, fellowships, scholarships, residencies, conferences, professional development opportunities, etc., for people of color; and offer free or discounted application, submission, membership, registration, and class fees, etc.

- More spaces, workshops, events, and networking opportunities should be created for translators of color.

- Translators of color should not be treated as spokespeople for diversity issues and should be offered opportunities beyond those in which only diversity/race is being discussed. All participants and attendees of events, workshops, and other programs—especially those who are white—have the responsibility to be vocal to the organizers of programs and events that feature only white translators.

- White publishers, editors, and translators have the responsibility to take on more of the extra work that many publishers, editors, and translators of color have been doing to combat racial inequities and exclusion in the field.

- Publishers and editors have the responsibility to interrogate and expand their understandings of language “mastery” and expertise, in consideration of translators with nontraditional language acquisition and immigration histories.

Translating Race and Authors of Color

Measures must also be taken to publish more authors of color in English translation. Translators, publishers, editors, and readers have a responsibility to examine the types of literature that are and are not being translated from different languages and cultures, including the inequities—in terms of both quantity and content—between literature by white authors and authors of color. Literary translation is a prime context in which translators can and should resist the drive to commodify cultural and linguistic differences by pushing the bounds of the styles, dialects, and discourses we use when translating authors of color and race within a text. Translators must continue to develop strategies that challenge the pervasive tendency to assimilate and domesticate texts into universalizing accounts of human experience. We should play an active role in destabilizing homogenizing cultural, linguistic, and canonical norms through the versions of texts we create.

- Translators, editors, and publishers have a responsibility to interrogate—and the right to be supported in challenging—the persistent use of standard dialects of U.S. and U.K. English, which are usually associated with norms of whiteness, as the default target language.

- Translators, publishers, and editors have a responsibility to be conscientious about and to support translation choices that are made in a text to explain concepts about a country, language, or culture that may be seen as not readily familiar, accessible, or understandable to a presumed general, Western, majority-white readership. This includes choices to leave words in the original language and whether or not to italicize them.

- Translators should be vigilant about not imposing U.S. conceptions of race on texts by authors writing from and about racial dynamics in other countries. Translators should strategically use language to challenge dominant paradigms of racial frameworks in the U.S. in order to highlight the complexity of such categories, their social and linguistic construction, and their diverse histories.

- When translating racism within a text, translators have a responsibility to examine the intentions behind the treatment of race and consider the harm certain choices may cause. One possible strategy for clarifying their attendant language choices is the inclusion of paratextual materials, such as introductions, forewords/afterwords, and translator’s notes.

- White translators have a responsibility to evaluate their positioning and qualifications in translating certain texts and, in some cases, to recommend translators of color instead.

- Translators, writers, and publishers have a responsibility to consider the implications of using a bridge translation, a practice in which a “literal” translation is prepared by a source-language expert and generally “polished” by a writer or translator with little or no knowledge of the source language. We need to interrogate the notions of difference between “literary” and “bridge” translators, which are often predicated on problematic and harmful ideas of literariness and language expertise that are inextricable from race, since bridge translations occur more frequently for translations from non-white-majority cultures where the source-language expert is treated as a “native informant” who cannot “master” English themselves. We understand “bridge” translations to be co-translations, which should be credited as such.

Publishing Market and Reception

Historically, how texts by authors of color have circulated and been received has been shaped by settler colonialism, imperialism, and chattel slavery, and these power relationships persist in U.S. publishing. The work of authors of color in translation is often fetishized and treated as a commodity to be consumed, an anthropological text providing access to an “exotic” culture, or an anti-racist text for the edification of a white audience. While some publishers have diversified their catalogs, the work of authors of color is often tokenized or asked to represent an entire culture, since so few texts by authors from non-white-majority cultures and/or writing in non-European languages are published in translation in the U.S.

- Publishers, editors, and translators must take into account the way the work is situated within the complex, historically determined relationship between the source text, its literary and cultural contexts, and the geopolitical and cultural imperialism of the U.S.

- Publishers, editors, and translators must question tendencies toward tokenization when marketing, publishing, and translating works from literary traditions underrepresented in the U.S. by engaging in critical dialogue at all stages of the publishing process to neither erase cultural specificity nor fetishize difference. Publishers, editors, and translators selecting texts for translation and publication must move beyond white supremacist norms of what makes for “great” literature. They must also avoid rejecting projects by authors of color with the excuse that “there is no market or reader” for such texts because they haven’t been published before.

- Publishers, editors, and translators should avoid cover art and other packaging and marketing materials that exotifies texts by authors of color.

- Reviewers and readers should reflect on the assumptions they bring to bear about the value and uses of translated literature by authors of color.

- Translators should draw attention to innovative perspectives on translation theory and practice, and this has to prioritize supporting and amplifying the work of translators and theorists of color, whose work is currently marginalized.

Gender Disparity in the Production of Translation in the U.S.

While feminist translation studies emerged in the 1990s, it is only recently that translators, editors, publishers, and readers have devoted relatively wider attention to gender disparity in terms of who is translated, who translates, and under what conditions. Initiatives such as Women in Translation Month and edit-a-thons to add women translators and authors to Wikipedia have sought to bring more readers to women authors in translation and advocate for more translations of their texts. Along with the Warwick Prize for Women in Translation, the shortlists for prestigious translation prizes such as the International Booker have recently featured a high number of women authors and translators. These high-profile translations, however, obscure the fact that at least twice as many books in English translation by men authors are still consistently published in the U.S. in comparison to books by women authors.

Unlike the case for women authors, in many languages, there are more women translators than men, yet men secure roughly the same number of contracts. Clearly, women’s voices and labor are still marginalized within the field. This lack of gender parity in the number of authors and translators published is inseparable from the sexism in the publishing industry, which VIDA has documented, dissected, and called out for the last decade. So far to address these inequities women have largely performed the additional labor in the form of data collection, pitching women authors to publishers, and promoting women in translation. Yet, these issues go beyond women authors and translators to the way the field treats gender more broadly.

Historically, the data that has been collected reflects a reductive binary approach to gender, pointing to deeper issues of inequity in the field. The methodology for collecting existing data on translation and gender, largely from the Publishers Weekly/Open Letter Database and the 2017 Authors Guild survey, elides or omits significant considerations. While the data tracks women in translation, translation databases and surveys usually do not provide options outside of the gender binary, with the exception of the recent 2021 American Literary Translators Association survey. The data also does not yet correlate gender with other key data points like income, race, educational level, institutional affiliation, and whether translation from their language receives institutional support. The information available leaves us with many more questions than answers, such as are women and nonbinary translators more likely to do unpaid labor? What percentage of men to women and nonbinary translators have academic jobs, and thus more access to institutional support? How do differences among languages and geographic regions impact the representation of women and nonbinary authors and translators? How does income break down based on gender? Funding and long-term investment are required for more granular data, but collecting and processing this data is only the first step toward working to address these inequities.

Publicity for literature by women and LGBTQ+ writers, translators and writers of color, and writers working within underrepresented literary traditions too often focuses on touting their “diversity,” while at the same time publishers and educational and cultural institutions fail to critically examine how their own practices continue to determine, and frequently limit, what literature is translated, published, disseminated, and promoted. The tendency to mask inequities via gestures such as awarding prizes and raising awareness about underrepresented authors is endemic to the publishing industry. We must interrogate why more women and nonbinary authors aren’t chosen for publication, and why men translators receive a disproportionate number of translation contracts despite representing a smaller percentage of translators. The approach to combating these inequities must be at least threefold: (1) an increase in the number of women and nonbinary translators who receive publishing contracts, and in the number of men who support and translate literature written by women and nonbinary authors; (2) an expansion across genres to make available a greater variety of work by women and nonbinary authors; and (3) in order to make these changes transformative and lasting, publishing institutions with material resources must commit to and invest in the work of women and nonbinary authors and translators.

Translation in the Academy

The translation of literary and humanistic texts is fundamental to academic knowledge production and the fabric of our global lives. For this reason, the twenty-first-century academy must evolve to foster an understanding of translation as a field of scholarly and creative practice with enormous value not only to researchers but also to students, both at the graduate and undergraduate levels. In spite of many clear advances in making the academy a more hospitable place for the practice and study of translation over the past fifty years, much work remains to be done to solidify the place of literary translation within the U.S. university.

First, although translation studies and translation theory have become a reputable academic enterprise since 1970, the practice of literary translation itself remains perversely marginalized. Professors routinely do not know how much translations “count” for tenure or are discouraged from undertaking translations at all. Courses in translation and translation studies remain far too few. In this context, the Modern Language Association’s 2011 guidelines for “evaluating translations as scholarship” offered a welcome early step toward correcting the extreme undervaluing of translation as a form of scholarship and creative endeavor, but the MLA recommendations must be adopted, amplified, and institutionalized by faculty leaders and administrators to produce real change in university norms and decision-making.

We call, in particular, for the creation of more programs, tracks, and certificates devoted to translation and translation studies, and for the hiring, tenuring, and promotion of more professors who make translation a core part of their creative and scholarly practice. Translators should be recruited and appointed not only in departments of literature but across the humanities and social sciences, where translation and its practice increasingly afford an indispensable lens for scholarship and undergird the very transmission of disciplinary knowledge. Such hiring should, moreover, take into account and work to remedy the underrepresentation of translators of color in full-time university translation positions.

Second, the academy must do more to impart an understanding of translation as a field and practice with value to both scholars and students. Undergraduate and graduate training in thinking critically about the production and dissemination of translations should be integral to any discipline that depends on texts in translation for its teaching and research. Such valorization of translation could take the form of independent courses, modules in other courses, and independent work (e.g., undergraduate theses, dissertations). Indeed, the case could be made that there should be an undergraduate course on translation at every U.S. university along the lines of the near-universal seminar in first-year writing.

Third, we believe that MFA and creative-writing programs bear a special—although typically unmet—responsibility toward literary translation. If creative-writing programs are designed to train students in established modes of craft, practice, and traditions of writing, and also to guide them in the creation and development of their own or new modes of craft, then translation as both a scholarly and creative practice must form part of this training and be treated with the same respect and rigor as other parts of the curriculum. Works in translation already part of creative-writing course reading lists should be taught as translations, which requires that instructors are trained to do so. We call further for an expansion of reading lists to include more works in translation taught as translations and an attendant shift in teaching approaches to demonstrate that translation is a creative art form with distinct craft concerns. Neglect of these concerns stands today as a significant oversight that encourages a “touristic” approach to international literature and reinforces an insular, monolingual U.S. literary culture. In this regard, creative-writing programs should make a special effort to teach translations of non-Western texts and non-Western translation criticism. Making more space for literary translation as creative writing requires increasing and diversifying the pool of translators and writers associated with universities, among both faculty and students, to include more writers of color, more writers who are speakers of languages other than English, more multilingual writers, and more writers with varied language-acquisition or immigration histories. We believe such changes are integral to the ideals of literary citizenship that creative writing programs endorse.

Fourth, translators of literary or other humanistic texts based at universities must be cognizant of the effects of their university employment on independent translators’ livelihoods. Because university-affiliated translators may experience less financial precarity than independent translators, university-affiliated translators must be heedful of the financial terms they accept for their labor and serve as advocates for, and be in solidarity with, their peers based outside the academy.

Publishers and Publications

We call on the U.S. publishing community to radically alter its relationship with translators and translation—to support and nurture translators and translation opportunities as a means to collaboratively challenge the existing reality of the U.S. literary industry and landscape. Translators should be hired in lead roles in the various facets of the industry that shape the production and dissemination of translations, as well as how they are understood and read. We also call on publishers to radically reimagine who the actual readership of translated literature is and could be, accounting for a diverse and engaged audience. We push back against the notion that U.S. readers are hostile to unfamiliar or difficult material.

These changes can only happen with a recommitment to the existing institutions that most thoughtfully support the publication of translations, as well as the cultivation of new ones.

As with our other concerns, practical as well as systemic issues must be addressed. We call for a reversal of the severe lack of investment in translated literature that has resulted from corporate consolidation within the publishing industry. Many of the independent publishers established in recent decades follow a similar practice; even those dedicated to literature in translation often do not offer sufficient rates and terms to translators. Too often, translators are still fighting for the copyright to their own creation to be registered in their name, to receive continuing royalties and subsidiary rights for various editions of their work, and for their name to be printed on the front cover of books they have translated. Literary journals and magazines should pay fees to translators whose work they publish. These are basic standards that should define the starting point for negotiating the terms of our relationship with publishers, and we call upon publishers and publications to engage with translators as collaborators and valued experts at every stage of the publishing process.

Publishers must create the systemic capacity for a greater number and variety of translated texts, as well as of translation and artistic practices. We challenge acquisition practices modeled by conglomerates that add only a nominal, profitable number of culturally different books to catalogues and backlists under the guise of multiculturalism and of supporting authors and translators of color, as well as women, queer, trans, nonbinary, genderqueer, D/deaf, disabled, and neurodivergent authors and translators. This version of “world literature” generates a misunderstanding in the U.S. of what translation is and does by casting translators as facilitators of “transparent” access to foreign cultures and subjectivities, and readers as consumers who vicariously experience those cultures in a fraught and compromised way.

Instead, we call for publishers and literary agents to engage translators to assist them in acquiring titles that more accurately reflect the literary landscapes of other languages and cultures, especially outside Europe, with better compensation for reader reports and sample materials; to nurture and promote a broader and more diverse pool of aspiring translators through mentorships, paid internships, and the establishment of prizes; to enlist bilingual editors to promote a comprehensive editorial process; and to maximize publicity for translated literature by centering these works and translators in their sales and marketing efforts.

Only by reimagining the parameters of the collaboration between publishers and translators can we effect transformative changes to more accurately and equitably reflect the significance of the cultural work that translators perform. In the end, we believe that cultivating a capacious spectrum of translated literature can lead us to engage diverse reading publics in robust discussion of the vital impact translation has on their responses to the books they hold in their hands and the pleasure they take in reading them.

Aesthetics and Creativity

We recognize that all creative work is done in dialogue with other work, and reject the old binary of original vs. copy. Every translation is inventive and distinctive, constituting a unique text. Translation reveals the fact that all art is collaborative. We advocate recognition of translators as literary artists in their own right, in addition to their role as curators and creators of new work.

Translators engage in the generative process of transforming one language into another. We are specialized writers who use formal, stylistic, and semantic strategies to create a text that corresponds, in terms of form, style, meaning, and more, to a prior text in another language. The translator cultivates a new voice for the text in the language of the translation by actively negotiating among diverse voices, literary forms, and implicit hierarchies. The choices we make, including which texts to translate and the myriad linguistic decisions within the work itself, have ethical and political implications, and are always in dialogue with existing literary and cultural traditions. Departing from immersion in the source text’s language and culture, translators often create what might seem strange, new, or even transgressive in terms of theme, tone, language, and form by using linguistic features such as syntax, dialect, register, loanwords, neologisms, and so on. The resulting creative disruption, rather than efforts to smooth the text to make it palatable or accessible to readers, can impact the receiving audience in ways that have historically contributed to the evolution of languages and cultures.

The aesthetics of translation, then, invite us to insist that readers and reviewers recognize that the translated text is the translator’s work. A translation is different from both a work initially composed in English and the source text. Ideally, the resulting work of art resonates in the receiving culture precisely because it reveals the inextricable links among the aesthetic, literary, and social effects of the translation.

Translation and Digital Worlds

The pervasive technologies that shape global culture have had a transformative influence on the role of translation in the digital arts and humanities. The digital environments in which we interact, and the languages we communicate in and through, have changed the nature of texts and the author/reader/translator dynamic. The virtual space has allowed more writers and potential translators to claim a place within it and to reach much larger and more diverse audiences than ever before. Whereas this technology reinscribes certain older inequities, it in turn creates new ones. At the same time, writers—particularly writers of color and writers from marginalized groups—who have historically been denied access to traditional print publishing venues may have increased opportunities to create and disseminate their work through multiple platforms. Digital publishing venues and digital or hybrid event programming also create greater access for D/deaf, disabled, and neurodivergent translators and readers, particularly via assistive technologies like screen readers; auditory, tactile, and visual notifications; audio descriptions; and captioning and transcripts. The COVID-19 pandemic has made it all the more clear that digital access is necessary to reduce barriers to translation events for disabled, poorer, geographically dispersed participants and those with caretaking responsibilities. Digital technologies thus facilitate connections among new and often underrepresented writers, translators, and other actors in the literary community and offers opportunities for social, cultural, and political activism through the translator’s art.

This is a new space, one in which the agency of the translator is magnified.

Increasingly, print and online literature actively incorporate intertextual, hypertextual, and visual elements or ekphrases of new digital media, as well as older forms of technology, such as film, photography, and television. New media changes the way art and literature are being produced, distributed, and consumed as well as changes the way participants in literary communities connect with each other locally and globally. How can literary, visual, and digital artists make technology a formal element of their work? How is technology, both old and new, represented and utilized in text production? How are data about translations collected, catalogued, and aggregated? How does new media alter the material distribution of culture, and how does readership evolve in a globalized media landscape? The mergers, boundaries, and protocols of new media have the potential to transform our understanding of the literature and culture produced or received today and in the future. All of these general questions relate to the role of translation and the nature of translation practice.

Digital technologies, including spaces for creating and experiencing art in text and installations, continue to blur the boundaries among verbal, visual, and musical texts, first in the way they are interpreted and then in the way readers and translators engage with them. Translation is built on the movement between languages and cultures. Increasingly, we can capture that movement visually or cognitively; for instance, the translation process can be recorded and visually displayed in real time, as in the case of installation art and electronic poetry, and the reader is invited to be actively involved as co-creator in a literal sense. Translators have the opportunity to direct their specialized knowledge, skills, and creative talent to rendering literature produced in dialogue with new media.

Coda

The calls for action in this manifesto represent our aspirations for the translation community and the role of literary translation in larger social and cultural contexts. In moving forward, we call upon all stakeholders—including publishers, editors, authors, educators, bloggers, social media influencers, sponsors, and translators, as well as the wider international audience—to continue this conversation and openly debate best practices and conceptual frameworks for advancing equity for translators and translation’s role in forms of activism and advocacy for social justice. This conversation should reach beyond the traditional European-North American axis to identify and cultivate new writing and new reading audiences in all world regions. We hope that this document will contribute to the evolution of the field for the next fifty years and that the profession will continue to interrogate its own aesthetic and political practices at all stages of the process. When literary translation becomes more inclusive and equitable, it will evolve in ways we cannot even imagine in this moment.

The working group that drafted this document would like to express gratitude to the many people who contributed their ideas and their time.

Susan Bernofsky

Bonnie Chau

Jonathan Cohen

Kate Costello

Karen Emmerich

Matthew Harrington

Michelle Hartman

Larissa Kyzer

Bruna Dantas Lobato

Elizabeth Lowe

J. Bret Maney

Mary Ann Newman

Adrienne Perry

Allison Markin Powell

Liz Rose

Maureen Shaughnessy

Corine Tachtiris

Laurel Taylor

April Yee

Alex Zucker

© This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.