Banned in the USA: State Laws Supercharge Book Suppression in Schools

State Laws Supercharge Book Suppression in Schools

Key Findings:

During the first half of the 2022-23 school year PEN America’s Index of School Book Bans lists 1,477 instances of individual books banned, affecting 874 unique titles, an increase of 28 percent compared to the prior six months

This school year, instances of book bans are most prevalent in Texas, Florida, Missouri, Utah, and South Carolina. The implications of bans in these five states are far-reaching, as policies and practices are modeled and replicated across the country.

This school year, numerous states enacted “wholesale bans” in which entire classrooms and school libraries have been suspended, closed, or emptied of books, either permanently or temporarily. These bans have involved the culling of books that were previously available to students, in ways that are impossible to track or quantify.

Update on Book Bans in the 2022-2023 School Year Shows Expanded Censorship of Themes Centered on Race, History, Sexual Orientation and Gender

As noted in PEN America’s previous Banned in the USA reports, the movement to ban books that has grown since 2021 is deeply undemocratic, as it seeks to impose restrictions on all students and families based on the preferences of a few parents or community members. The nature of this movement is not one of isolated challenges to books by parents in different communities; rather, it is an organized effort by advocacy groups and state politicians with the ultimate aim of limiting access to certain stories, perspectives, and information.

For two years PEN America has tracked the growth of this movement, documented in the proliferation of groups advocating for book bans, the spread of mass challenges to long lists of books, the revision of local school district policies and procedures, and the enactment of new legislation and state-level policies. These efforts have led to an escalation in book bans in public schools across states.

PEN America’s Methodology

This data snapshot reports bans where the initiating action for the ban occurred between July 1 and December 31, 2022. We track instances of books bans at the district-level, meaning one case of a ban is when a book title is removed from access within a school district. PEN America records book bans through publicly available data on district or school websites, news sources, Public Records Requests, and school board minutes.

The data presented here is limited. The true magnitude of book banning in the 2022-23 school year is unquestionably much higher. PEN America’s researchers continue to discover books banned in the previous year, thus our reporting may not be comprehensive of all books removed from access during the six-month reporting period. Books are often removed silently and not reported publicly or validated through Public Records Requests. For a full discussion of our methodology, see our Frequently Asked Questions.

What is a book ban?

PEN America defines a school book ban as any action taken against a book based on its content and as a result of parent or community challenges, administrative decisions, or in response to direct or threatened action by lawmakers or other governmental officials, that leads to a previously accessible book being either completely removed from availability to students, or where access to a book is restricted or diminished.

It is important to recognize that books available in schools, whether in a school or classroom library, or as part of a curriculum, were selected by librarians and educators as part of the educational offerings to students. Book bans occur when those choices are overridden by school boards, administrators, teachers, or even politicians, on the basis of a particular book’s content.

School book bans take varied forms, and can include prohibitions on books in libraries or classrooms, as well as a range of other restrictions, some of which may be temporary. Book removals that follow established processes may still improperly target books on the basis of content pertaining to race, gender, or sexual orientation, invoking concerns of equal protection in education. For more details, please see the first edition of Banned in the USA (April 2022).

Types of book bans

PEN America’s Index of School Book Bans differentiates among four discrete categories of bans: banned in libraries and classrooms; banned in libraries; banned in classrooms; and banned pending investigation. An affected title can be found in different categories of bans in different districts.

The banning of a single book title can mean anything from one to hundreds of copies pulled from libraries or classrooms in a school district; often, the same title is banned in libraries, classrooms, or both in a district. PEN America does not count these duplicate book bans in its unique title tally, but does acknowledge each separate ban in its overall count.

- Banned in libraries and classrooms: Instances where individual titles were placed off-limits for students in either some or all libraries and classrooms, and simultaneously barred from inclusion in curricula.

- Banned in libraries: These represent instances in which administrators or school boards have removed individual titles from school libraries where they were previously available. Books in this category are not necessarily banned from classroom curriculum. This category includes decisions to ban a book from one school-level library (e.g. a middle school) even if it is transferred to or included in libraries for higher grades (e.g. a high school), or other forms of grade-level restrictions. In many such cases, the decisions to ban books from lower-level libraries do not align with publishers’ age recommendations.

- Banned in classrooms: Instances where school boards or other school authorities have barred individual titles from classroom libraries, curriculum, or optional reading lists. These constitute bans on use in classrooms, even in cases where the books may still be available in school libraries.

- Banned pending investigation: Instances where a title was removed during an investigation to determine what restrictions, if any, to implement on it. In cases where such investigations have concluded, and particular titles have been further restricted or banned as a result, PEN America uses one of the categories above. Though timelines vary across districts, investigations can be time-consuming, resulting in bans on particular titles that last months at a time. These restrictions are recorded as bans because they 1) remove access to books, even if temporary, and 2) are counter to procedural best practices for book challenges from the American Library Association (ALA) and the National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC). Detailed definitions can be found in the first edition of Banned in the USA (April 2022).

PEN America found that of the 1,477 ban cases between July and December 2022, 52% (n=761) were banned pending investigation, 25% (n=364) were banned in libraries and classrooms, 23% (n=345) were banned in libraries and <1% (n=7) were banned in classrooms.

Sometimes schools and districts enact immediate, permanent prohibitions on books. In other instances, authorities immediately suspend books from student access while undergoing a period of review. The large number of books in the “banned pending investigation” category reflects the latter dynamic. Many of these books are removed from student access before due process of any kind is carried out; in many cases, books are removed before they are even read, or before objections to books are checked for basic accuracy.

For example, 97 books challenged at once in October 2022 in Beaufort, South Carolina were immediately pulled from access, pending review. Students are still asking for them to be returned, six months later. In Escambia, Florida, books that were challenged in September 2022 were moved into restricted backrooms. To access books under review, students were required to get parents’ permission to check them out or in some cases, to just look at the books. In Clay County, Florida, by December 2022 of this school year, at least 100 books were pulled from access after being challenged, following complaints by a single person.

Banned Books: More Books, Varied Content, and New Titles

During the first half of the 2022-2023 school year, PEN America recorded 1,477 instances of individual books banned, an increase of 28 percent compared to the prior six months, January – June 2022. That is more instances of book banning than recorded in either the first or second half of the 2021-22 school year. Over this six-month timeline, the total instances of book bans affected is over 800 titles; this equates to over 100 titles removed from student access each month.

| July-December 2021 | January-June 2022 | July-December 2022 | |

| Instances of book bans | 1,383 | 1,149 | 1,477 |

Banned content and titles

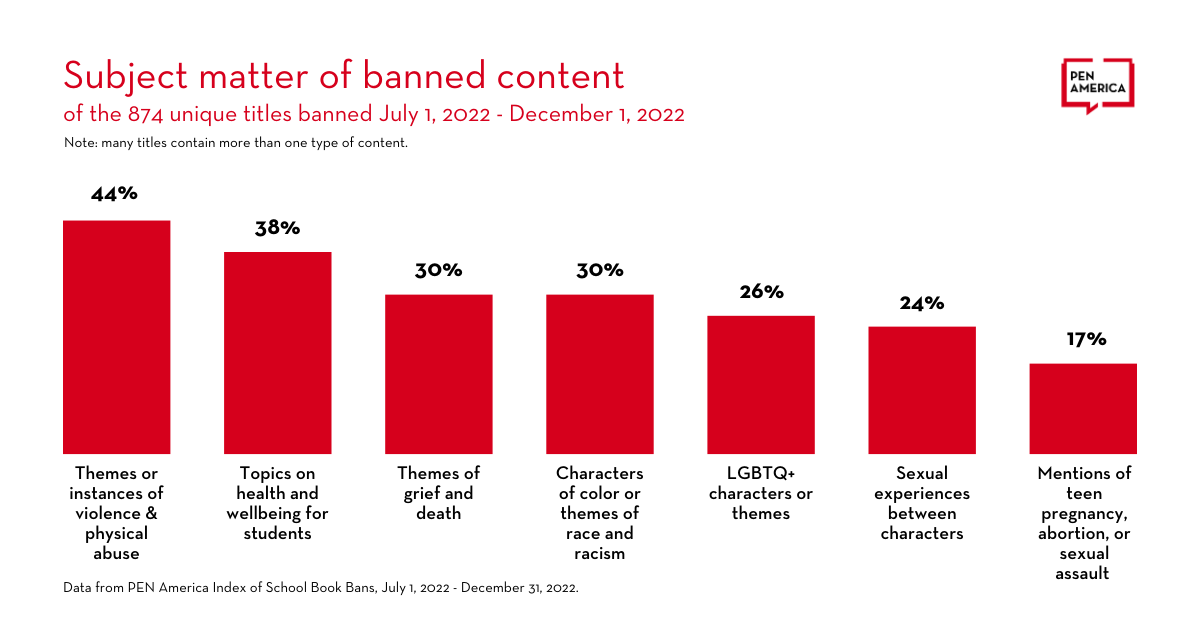

The 1,477 instances of book bans PEN America tracked this school year affected 874 unique titles. Book bans continue to target books featuring LGBTQ+ themes or LGBTQ+ characters, characters of color, and books on race and racism. This school year, several content categories appeared more commonly among banned books than in the previous school year; this fall’s banned books include more titles that touch on violence and abuse, health and wellbeing, or that include instances or themes of grief and death. This is largely due to the removal of long lists of books, often covering a wide swath of topics, which are frequently “banned pending investigation.”

Of the 874 unique banned book titles in the Index,

- 44% include themes or instances of violence & physical abuse (n=385). This includes titles that have episodes of violence and/or physical abuse as a component of plot or discussion.

- 38% cover topics on health and wellbeing for students (n=331). This includes content on mental health, bullying, suicide, substance abuse, as well as books that discuss sexual wellbeing and puberty.

- 30% are books that include instances or themes of grief and death (n=264). This includes books that have a character death or a related death that is impactful to the plot or a character’s emotional arc.

- 30% include characters of color or discuss race and racism (n=260)

- 26% present LGBTQ+ characters or themes (n=229). Of note, within this category, 68 are books that include transgender characters, which is 8% of all books banned.

- 24% detail sexual experiences between characters (n=211).

- 17% of books mention teen pregnancy, abortion, or sexual assault (n=150)Note: categories less than 10% are not reported; categories are developed based on researcher assessment of banned books, categories are matched to individual titles using publisher summaries, Amazon Books and Goodreads, and expert opinions of librarians and authors.

These categories are often overlapping; several content areas intersect in most books. Together, the content of banned books illuminates how the movement to censor books affects a diverse and varied set of identities, topics, concepts, and stories.

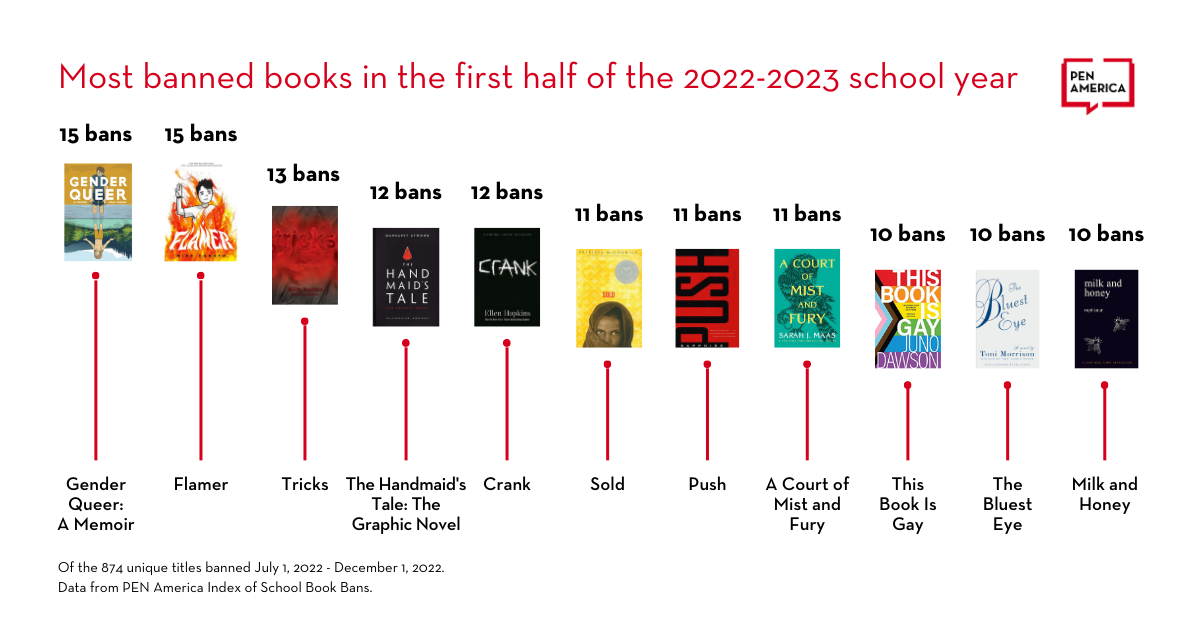

So far this school year, 11 of the 874 unique titles were banned in ten or more school districts. This list of the most frequently banned books includes a cross section of the content areas presented above, and indicates how efforts to remove books continue to target authors of color and LGBTQ+ authors, as well as books that center LGBTQ+ characters and characters of color.

Learn more about the 11 Most Banned Books of the Start of the 2022-2023 School Year.

Each of these titles have been banned in at least 10 or more districts this school year. Among the top eleven books, ten of eleven authors and illustrators are women or non-binary individuals. Four of the books are written by authors of color and four by LGBTQ+ individuals, identities historically underrepresented in publishing and in school libraries.

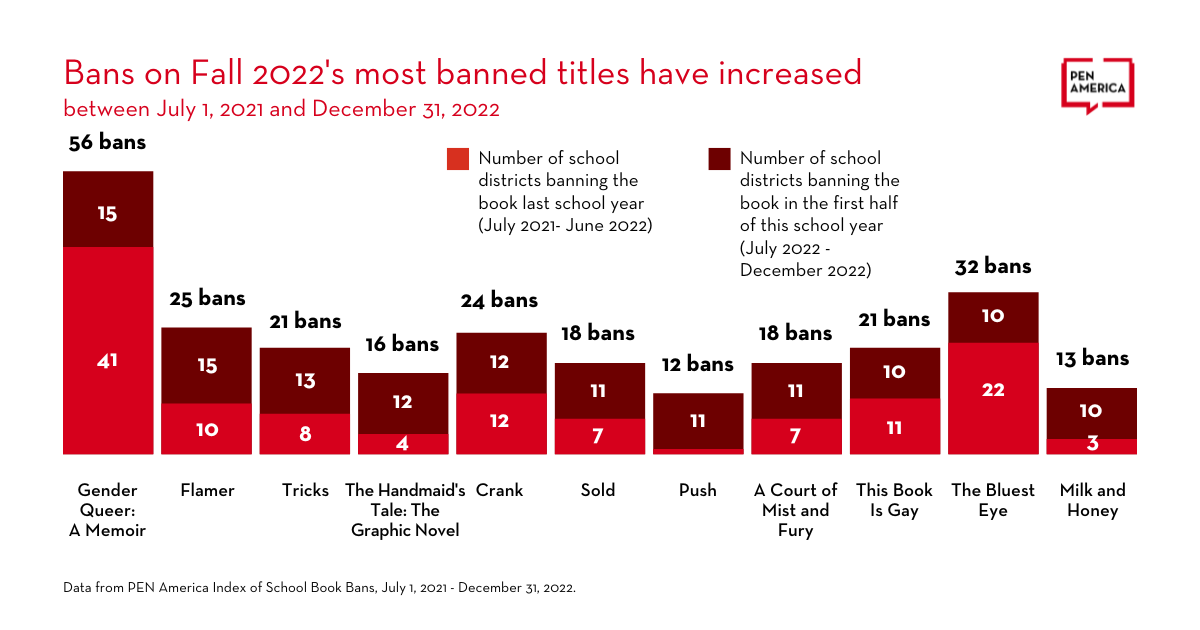

The graphs below includes the 11 most frequently banned books by the number of school districts to ban the title during the 2021-2022 school year and the number of districts to ban the same title so far in the 2022-23 school year to show how these books are continuously targeted.

The majority of these titles were banned in more districts in 2022-23 than 2021-22. New books can also become sudden targets. For example, Push by Sapphire, a novel that narrates the life of a Black teenage parent who was raped by her father, and Milk and Honey by Rupi Kaur, a poetry collection touching on themes of violence, abuse, love, loss, and femininity, were seldom challenged last school year, but have been removed in at least 10 school districts in just the first half of this school year.

Of note, several books that were frequently banned last school year, such as All Boys Aren’t Blue by George M. Johnson and Out of Darkness by Ashley Hope Pérez, have been banned in significantly fewer districts this year. All Boys Aren’t Blue, for example, was banned in 29 districts last year; this year the book has been banned in nine. Out of Darkness was banned in 24 districts last year and this year in seven. Presumably, this is in part because the districts likely to have banned these books have already done so, or librarians may have stopped adding them to their collections. A similar phenomenon surrounds The 1619 Project, created by journalist and author Nikole Hannah-Jones, which has in some states been prevented from being acquired in schools. Texas passed a law that teachers “can’t require an understanding” of the work, and the Florida State Board of Education approved a rule explicitly prohibiting material from the Project from being taught.

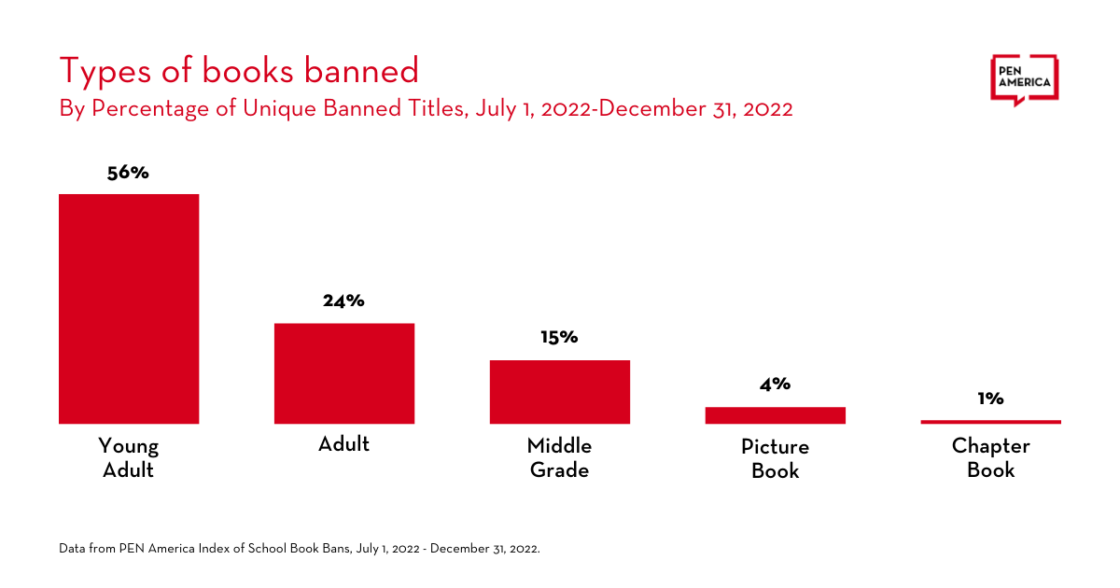

Targeting YA Books & A Case Study of Picture Books

Books banned during the first half of the school year represent a range of titles for intended audiences, with most bans affecting Young Adult (YA) Books. YA books are understood as texts that help students gain knowledge about the contemporary world, their own sense of identity, and social responsibility, and serve as a tool for developing empathy. An overview of the types of books banned so far this school year is below:

Examining the intended readers of books and the kinds of stories most often banned also offers insight into the impact of these book bans on students of all ages. For example, of the 35 picture book titles banned between July and December 2022, 74% (n=26) are stories that feature LGBTQ characters and 46% (n=16) feature characters of color or discuss race and racism. Stories about diverse identities have only recently been added to library shelves; in this moment of escalating book bans, they are some of the prime targets for removal.

State by State: Texas and Florida Continue to Lead in Book Bans

Between July and December 2022, instances of individual book bans occurred in 66 school districts in 21 states. PEN America recorded 13 districts in Florida banning books, followed by 12 districts in Missouri, 7 districts in Texas, and 5 districts in both South Carolina and Michigan. Texas districts had the most instances of book bans with 438 bans, followed by 357 bans in Florida, 315 bans in Missouri, and over 100 bans in both Utah and South Carolina.

The map below provides an overview of book bans by state.

Total Instances of Book Bans by State (July 2022 – December 2022)

So far this school year, instances of book bans were concentrated in a few states – Texas, Florida, Missouri, Utah, and South Carolina. This concentration is in part due to some districts which removed large lists of books when they were challenged, removing them from student access for indefinite periods of review. Frisco Independent School District in Texas, Wentzville School District in Missouri, and Escambia County Public Schools in Florida together banned over 600 books, whereas most districts nationwide (76%) banned between 1 and 19 books. Though some of these districts’ bans proved temporary and some books were returned to shelves, each case involved summarily removing books before any considered evaluation took place. Such bans “pending investigation” are contrary to best practice guidance for the review of challenged books in public schools, which PEN America has discussed previously.

Authors and Illustrators Impacted

In taking a closer look at the effects on writers and other creative voices, book bans between July and December 2022 affected 848 individuals – 688 different authors, 155 illustrators, and 11 translators. It is likely that by the end of the 2022-2023 school year, book bans will exceed last year’s total of over 1,500 creative people affected.

Several authors have been banned in multiple districts and states. As in the 2021-22 school year, Ellen Hopkins, a novelist who writes for young adult and adult audiences, remains the “most banned author” so far in 2022-23, with 89 bans in 20 districts targeting 17 unique titles.

The most frequently banned authors between July and December 2022 are presented in the table below.

| Author | Districts banning books | Instances of books banned | Unique titles banned |

| Ellen Hopkins | 20 | 89 | 17 |

| Elana K. Arnold | 16 | 26 | 5 |

| Maia Kobabe | 15 | 15 | 1 |

| Mike Curato | 15 | 15 | 1 |

| Margaret Atwood | 15 | 25 | 4 |

| Sarah J. Maas | 14 | 61 | 12 |

| Rupi Kaur | 14 | 19 | 3 |

| Sapphire | 11 | 11 | 1 |

| Toni Morrison | 11 | 14 | 3 |

| Patricia McCormick | 11 | 11 | 1 |

| Lauren Myracle | 10 | 18 | 6 |

| Juno Dawson | 10 | 10 | 1 |

| Jesse Andrews | 10 | 14 | 2 |

The Book Banning Movement: Groups, Politicians, and Legislation

Of the 1,477 reported book ban cases this school year, 74% are connected to organized efforts, mainly of advocacy groups; elected officials; or enacted legislation (n=1,085).

Of these, 20% (n=294) are connected to organized advocacy groups, meaning actions by them influenced a book ban. The most influential of these groups, Moms for Liberty, is connected to 58% (n=170) of all advocacy-led book bans around the country (n=294). These 170 bans occurred in six districts across North Dakota, South Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Florida.

Additionally, 25% (n=372) of individual books banned were connected to political pressure from elected or appointed officials. These officials wielded their government position to explicitly challenge books in ways that can intimidate and chill school administrators and educators. In Texas, State Representative Jared Patterson, challenged books in his district and publicized the challenges on his office’s website. In another Texas school district, 58 books were pulled for review based on a list of 850 “vulgar” books circulated by another Texas state representative, Matt Krause, a year earlier.

Lastly, 31% (n=461) of book ban instances were connected to newly enacted state laws in Florida, Utah, and Missouri. As elaborated below, these include laws that contain direct prohibitions on certain content in schools, specify new rules about how books need to be cataloged or new conditions under which they can be accessed, or threaten punishments for teachers, librarians and administrators if they provide students access to material deemed “harmful” or “explicit.” Local individuals and groups are using these laws to petition schools to remove books, claiming that specific titles violate new rules or prohibitions or should incur punishments.

The Chilling Effect of Vague Legislation

Across a number of states during the 2022-2023 school year, new laws give decision-makers incentives to take an overly censorious approach to the content, identities, images, and ideas available in classrooms and libraries. Vague language in the laws regarding how they should be implemented, as well as the inclusion of potential punishments for educators who violate them, have combined to yield a chilling effect.

In Florida, for example, a trio of laws enacted this school year bar instruction on sexual orientation or gender identity in kindergarten through third grade (HB 1557), prohibit educators from discussing advantages or disadvantages based on race (HB 7), and mandate that schools must catalog every book on their shelves, including those found in classroom libraries (HB 1467). Due to the lack of clear guidance, these three laws have each led teachers, media specialists, and school administrators to proactively remove books from shelves, in the absence of any specific challenges. In October 2022, the Florida Board of Education also passed new rules that go beyond the language in the laws, to stipulate that teachers found in violation of these bills could have their professional teaching certification revoked.

In Missouri, a law that was originally written to create important new protections for sexual assault survivors (SB 775) was amended before passage to include a provision making it a Class A misdemeanor for librarians or teachers to provide “explicit sexual material” to a student. The measure’s definition of “explicit sexual material” is sweeping, applying to any visual depiction of a range of physical attributes or acts. When the law went into effect in August 2022, public school districts across the state banned 313 books out of fear of criminal punishment. As stated by a school district representative in Missouri following the passage of SB775:

“The unfortunate reality of Senate Bill 775 is that, now in effect, it includes criminal penalties for individual educators. We are not willing to risk those potential consequences and will err on the side of caution on behalf of the individuals who serve our students.”

Per one analysis, more than half of the books pulled in Missouri were about or written by LGBTQ+ people or people of color. One such book banned in multiple districts across Missouri is Milk and Honey by Rupi Kaur, who stated:

“It’s so unfortunate and kind of disturbing just to see the way those poems about our experiences — about the abuse that we endure — are now the reason that this book is being banned.”

In February 2023, the Missouri ACLU filed suit against SB 775, representing two Missouri library associations, arguing that the law is unconstitutionally vague, and has led to book bans that violate students’ First Amendment rights.

Utah’s “Sensitive Materials in Schools Act,” (HB 374) similarly went into effect this school year, and “prohibits certain sensitive instructional materials in public schools.” After the law was passed, the state attorney general’s office issued guidance directing school districts “to immediately remove books from school libraries that are categorically defined as pornography under state statute.” In response, Alpine and Washington County school districts in Utah banned dozens of books, including The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison, I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter by Erika Sánchez, The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood, Forever… by Judy Blume, and Looking for Alaska by John Green. These works of literature do not remotely fit the well-established legal and colloquial definitions of “pornography.” Further, in Alpine, 18 of the 39 titles (46%) removed feature LGBTQ+ characters; and in Washington, where 42 books were banned, half included sexual experiences (n=21) and over 30% (n=15) prominently feature characters of color or discuss race and racism.

As PEN America has previously explained, the legal test for obscenity requires a holistic evaluation of the material. Over the last year, however, terminology such as “obscene,” “pornographic,” “harmful to minors,” and “sexually explicit” is being utilized to restrict a range of content, including books on LGBTQ+ experiences, stories that include any sexual references, sex education materials, books that include portrayals of death or abuse, and art books. In Missouri and Utah, books are frequently targeted for short excerpts or even single images, without the holistic evaluation necessary to understand their literary merits.

The table below provides some examples of how laws in these three states have been interpreted in practice, resulting in a range of books banned. These three states demonstrate how legislation is deepening an environment of censorship, where fear and intimidation leads to an overly cautious response.

| State | Description of Policy | Implementation of Policy |

| Florida | H.B. 1557: The “Parental Rights in Education Act” (a.k.a. the “Don’t Say Gay” law) states that “Classroom instruction by school personnel or third parties on sexual orientation or gender identity may not occur in kindergarten through grade 3 or in a manner that is not age-appropriate or developmentally appropriate for students in accordance with state standards.” In a motion to dismiss a lawsuit, lawyers representing the State of Florida argued that the HB 1557 does not apply to school libraries, only to classroom instruction. | In practice, numerous school districts have interpreted HB 1557 as mandating that they should remove books with any LGBTQ+ content from classroom and school libraries. Some of the books removed following the legislation’s passage include: Call Me Max by Kyle Lukoff I am Jazz by Jessica Herthel and Jazz Jennings And Tango Makes Three by Justin Richardson and Peter Parnell |

| Utah | H.B. 374: “Sensitive Materials in Schools” law prohibits “sensitive materials” in schools, and the state attorney general’s office directed school districts to remove books “that are categorically defined as pornography under state statute.” | In practice, schools have removed works of literature for containing any sexual content. Some of the books include: The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter by Erika Sánchez The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood Looking for Alaska by John Green This Book is Gay by Juno Dawson Forever… by Judy Blume |

| Missouri | Provision in S.B. 775 makes the distribution to students of material deemed “harmful to minors” by any school official (educators, librarians, student teachers, coaches) or by any visitor to a school, a misdemeanor punishable by fines or jail time. | In practice, schools have removed works of literature for containing any sexual content. Some of the books include: The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter by Erika Sánchez The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood Looking for Alaska by John Green This Book is Gay by Juno Dawson Forever… by Judy Blume |

Though their impact has yet to be documented in as much detail, several additional state laws passed in 2022 are having an impact on the availability of books in schools, and likely contributing to a chilling effect.

In Tennessee, the passage in 2022 of the “Age-Appropriate Materials Act” (SB 2407) led to an August memorandum that mandated cataloging of books in classroom and school libraries. A series of “wholesale bans” were reported by teachers on social media or in school board meetings in response, as they decided to remove classroom library collections rather than put themselves at risk of punishment. As discussed below, “wholesale bans” are difficult to quantify, and thus are not captured in PEN America’s Index of School Book Bans.

Laws passed last year in Georgia and Tennessee mandate new processes for evaluating book challenges, which may well spur bans, too. Georgia’s law (SB 226) gives school principals the power to resolve book ban challenges on their own, but affords them only ten days in which to read a book and make an informed decision. Tennessee’s law mandates the creation of a new politically-appointed committee to settle appeals from school districts concerning objections to materials, effectively giving a small group of individuals the power to ban books permanently from every public school statewide.

In Virginia, a state law now in effect (SB656) requires the Department of Education to develop model policies to ensure parents are notified if students are being taught “sexually explicit” instructional materials in the classroom. In one district, Board members expanded upon the state’s “model policy” to include notifications for materials in school libraries, in addition to classrooms, making the removal of books from libraries a more likely outcome. In Arizona, a 2022 law (HB 2495) now requires parental approval to teach books or other material that make any references to sex. This law is likely to have a chilling effect on educators, who may avoid any materials likely to spark controversy or complaint.

Wholesale Bans Following State Legislation

In addition to specific instances of book bans following legislation, there were also cases where entire classrooms and school libraries have reportedly been suspended or emptied of books this school year. As a result of these “wholesale bans,” the data presented above unquestionably undercounts the true magnitude of book censorship that has taken place in schools this school year. PEN America defines cases when entire classrooms and school libraries have been suspended, closed, or emptied of books, either temporarily or permanently, as “wholesale bans.” Because such cases are difficult or impossible to quantify, they are not included in PEN America’s Index of School Book Bans.

These “wholesale bans” generally involve culling large numbers of books previously available to students following directives to teachers and librarians to catalog collections for public scrutiny, typically within short timeframes and under threat of punishment from newly enacted state laws. Images of closed-off classroom libraries, like three book shelves from the School District of Indian River County, Florida or of empty shelves such as in Tennessee in August 2022, illustrate the alarming effect of these wholesale bans. These bans also reflect the chilling effect of the book ban movement, which can lead to preemptive removals of books before they are individually challenged. As one Missouri librarian explained in Coda:

“We had one librarian who began pulling absolutely everything because the fear became so overwhelming… Others wound up shutting down their library for periods of time just so they could ensure they had gone through everything.”

In Defense of the Freedom to Read

The data on book bans between July and December 2022 presented above demonstrates how the movement to remove books from public schools has continued to gain steam. So far, this school year recorded the highest number of books banned in a school semester, with efforts concentrated in Texas, Florida, and Missouri. Several books, such as Gender Queer, This Book Is Gay, and The Bluest Eye continue to be targets of censorship, while books such as Flamer, Push, and Milk and Honey were more frequently banned this school year than last.

As the movement continues to shift and expand, this fall 2022 snapshot illustrates how the effort to censor specific identities and concepts, mainly LGBTQ+ characters and characters of color or books on race and racism, broadened to also diminish access to books that touch on varied aspects of the human experience, including books on violence, abuse, health, wellbeing, grief, and death. This report also illuminates the increasing role of legislation in driving decision-makers to proactively restrict books, and creating an environment of fear and intimidation.

Looking ahead, PEN America’s preliminary tracking of the second half of the 2022-2023 school year suggests censorship efforts are still ramping up. In defending the freedom to read, we are increasingly concerned by the burden and cost that this movement to ban books places on public schools, as well as students, administrators, educators, and librarians.

Book bans impede the freedom to read, limiting students’ access to a diversity of views and stories. School libraries serve the educational process by making knowledge and ideas available, and ensuring books remain available for all regardless of personal or political ideologies and ideas. In approaching the 2023-2024 school year, we recommend policymakers, school boards, and district administrators consider the many reasons for including and celebrating books rather than restricting them.

Acknowledgements

This report was written by Kasey Meehan, program director, Freedom to Read, Jonathan Friedman, director, Free Expression and Education Programs, and Freedom to Read program consultants, Tasslyn Magnusson, PhD, and Sabrina Baêta. The report was reviewed and edited by Nadine Farid Johnson, managing director of PEN America Washington and Free Expression Programs and Summer Lopez, chief program officer, Free Expression. Lisa Tolin provided editorial support, and Daniel Cruz and Apollo Chastain provided critical support for data collection and analysis. PEN America is grateful for support from The Endeavor Foundation and the Long Ridge Foundation which made this report possible, as well as to also thanks key partners in this work, including the Florida Freedom to Read Project and Let Utah Read. Finally, we extend our gratitude to the many authors, teachers, librarians, parents, students, and citizens who are fighting book bans, speaking at school board meetings, and raising attention to these issues, many of whom inspired and informed this report.