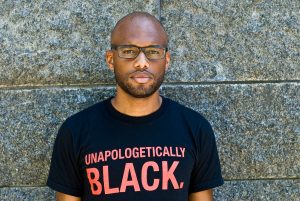

The PEN Ten with Mychal Denzel Smith

By Brianna Goodman

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week we speak to Mychal Denzel Smith, author of Invisible Man, Got the Whole World Watching: A Young Black Man’s Education (Nation Books, 2016).

1. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity”?

There are so many different parts that compose an identity; being a writer is among mine. What I think the question is attempting to get at is what effect those things we mark as identity—gender, race, sexuality—have on my writing. I have never not been black. I am a man, after spending many years as a boy, and because I am the same gender as I was assigned at birth, I am cis. My sexuality is most neatly understood as heterosexual, though the term irons out any experiences and desires that aren’t readily identifiable as heterosexual. Much of my writing is an interrogation of these identities and the systems that create their distinctions. I am not a writer above or separate from these things. I am not a writer who just so happens to be black. I am black, cis, male, hetero, a writer, a brother, a son, a friend, a partner, a mentor, a mentee, an activist, a reader, a millennial, a sneakerhead, and many other things all at once. Each part of my identity informs the other parts. No writer shuns identity; “the writer’s identity” is only that which they choose to bring to the fore.

2. In an era of “alternative facts” and “fake news,” how does your writing navigate truth? And what is the relationship between truth and fiction?

Pardon me as I become “that guy who quotes Foucault,” but what he said here is, I think, useful: “‘Truth’ is to be understood as a system of ordered procedures for the production, regulation, distribution, circulation, and operation of statements. ‘Truth’ is linked in a circular relation with systems of power that produce and sustain it, and to effects of power which it induces and which extend it—a ‘regime’ of truth.” I know that fantasizing about the bygone days of an unencumbered truth can be soothing, but that is pure fantasy. The terms “alternative facts” and “fake news” may be new to us, but what is the grand narrative of U.S. history except a series of “alternative facts”? That is not by accident. It is, as Foucault notes, through “the production, regulation, distribution, circulation, and operation of statements” meant to function as “truth.” Truth is only that which we believe, and what we are compelled to believe is based on our relationship to power. To the question, my work navigates truth by understanding it as a struggle to reshape power.

3. Writers are often influenced by the words of others, building up from the foundations others have laid. Where is the line between inspiration and appropriation?

Plagiarism.

4. “Resistance” is a long-employed term that has come to mean anything from resisting tyranny, to resisting societal norms, to resisting negative urges and bad habits, and so much more. It there anything you are resisting right now? Is your writing involved in that act of resistance?

I’m resisting using the word “resistance” as its meaning gets further diluted by a politics that seeks only to restore a sense of “normalcy,” as if the ideology of reactionaries and conservatives has not long dominated the American political order. My writing is more interested in imagining beyond resistance.

5. What do you consider to be the biggest threat to free expression today? Have there been times when your right to free expression has been challenged?

Same threat as it has always been: those whose power would be threatened by the collapse of social, political, and economic hierarchies.

6. What’s the most daring thing you’ve ever put into words?

That’s for others to decide. I don’t ever think of my work in those terms.

7. Have you ever written something you wish you could take back? What was your course of action?

No. If I had it my way, there are things I would still be editing/perfecting, but part of understanding writing as a career is accepting that you have to let go of things in their imperfect form. I have written things that I later disagreed with. But what I hope is that anyone interested in looking at my entire body of work would be able to note the progression and growth and challenges posed to myself. I would prefer my writing to stand as a reflection of myself in that moment, flaws and all.

8. Post, stalk, or shun: What is your relationship to social media as a writer?

It has shifted over time. I used to post much more, and it subsided the more writing opportunities I had. Now I talk too much, I hardly know what to say on social media. I also find that it’s not as conducive to the kinds of conversations I once had there. I’m already getting fogeyish on social media, but I have genuinely noticed a change in the way people conduct themselves and have “conversations” that feel more like the construction of a persona rather than an honest engagement with other people. And that’s fine! Use the tool as you see fit. But I find it less interesting for myself. However, I’m still addicted to it as a product, so I suppose I’d fit into the “stalk” category, though “lurker” may be a better term since it doesn’t have the same creepy/criminal connotation.

9. There is so much at stake in today’s world that citizens often say they don’t know where to focus their attention. As a writer and a social commentator, how do you choose where to place your energy? How do you approach the daily onslaught of news?

Irrationally. I have convinced myself that so long as I am paying attention to every tiny detail of the news then nothing catastrophically bad can happen. That’s obviously not true, and it’s important for me to remind myself of that constantly. Consuming the minutiae will prevent me from getting anything done. I reserve my energy for the things that excite me, stimulate me intellectually, pose some fantastic challenge, or anger me deeply. This is still a lot, but I’m not useful everywhere. I go where I feel most useful.

10. Finally, can you tell us about a piece of writing that has influenced you that readers might not know about?

It’d be fairly pretentious to assume I’ve read something that no/few other people have read, but Toni Morrison’s 1976 essay “The Black Experience; A Slow Walk of Trees (as Grandmother Would Say) Hopeless (as Grandfather Would Say)” is one I hold dear. She writes: “They have been dead now for 30 years and more and I still don’t know which of them came closer to the truth about the possibilities of life for black people in this country. One of their grandchildren is a tenured professor at Princeton. Another, who suffered from what the Peruvian poet called ‘anger that breaks a man into children,’ was picked up just as he entered his teens and emotionally lobotomized by the reformatories and mental institutions specifically designed to serve him. Neither John Solomon nor Ardelia lived long enough to despair over one or swell with pride over the other. But if they were alive today each would have selected and collected enough evidence to support the accuracy of the other’s original point of view. And it would be difficult to convince either one that the other was right.” Read the whole thing.