“To Remember is a Kind of Resistance”: A PEN Ten Interview with Julian Randall

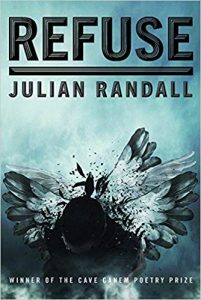

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, guest editor Natalie Desroisers, the programs and communications fellow at Cave Canem, speaks to poet Julian Randall. Hear Randall read from his debut collection, Refuse, winner of the 2017 Cave Canem Poetry Prize, alongside prize judge Vievee Francis on November 29, 7pm, at the NYU Lillian Vernon House.

1. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity”?

Well, I’m Black and also Latinx and also Bisexual and also suffer from depression and that’s the house and some of the traditions from which I write. Like many folks I began to write when I could no longer bear living in a world that refused to see me. Like Toni Morrison once said “If there is a story you desperately want to read, you must be the one to write it.” I write from that imperative, because too much of my life and the life of other people like me were decided by people who could not or would not conceive of us. I am working still, because it’s not a destination I believe, to continue to get better at writing unabashedly towards my folks. My identity so often has been theorized to be split, deficient, not enough of anything. I write not necessarily against that because I don’t think it’s a worthwhile use of my time to write trying to disprove people who don’t want to see me as human, rather my work is proof that that narrative is false and I’m glad so many people have found something they know to be true, someone like themselves in what I’ve written.

“Like many folks I began to write when I could no longer bear living in a world that refused to see me.”

2. In an era of “alternative facts” and “fake news,” how does your writing navigate truth? And what is the relationship between truth and fiction?

I think the work I’m doing now has been a really difficult parsing of what “truth” can mean when I’m doing work to try and trace my family’s history of enslavement in Mississippi. It’s a long story that’s still in progress but many of the records appear to be irrevocably lost so what can I do to make truth of that in a traditional sense? As a result, I think I have been trying to mine imagination as a kind of truth building for this next project. Something that Refuse taught me in the writing of it was that to hold myself to a standard of 100% accuracy was 1. Unachievable 2. A standard that was only serving to suffocate the poems. I do my best to be rigorous with memory, to approach from many angles, to allow room for doubt because that feels less like writing a lie. I think this administration is a great argument for the usefulness of doubt honestly, these people tell colossal lies, follow colossal lies, kill daily and without relent over colossal lies and there’s not a lick of doubt in them. Why would I ever want to write with that kind of energy, the violence I could make with that? Not for me fam, hard pass.

3. Writers are often influenced by the words of others, building up from the foundations others have laid. Where is the line between inspiration and appropriation?

You have to be willing to read widely and give credit for that whenever it’s appropriate. My own personal rule of thumb is to ask “Would you have arrived at this line without having read this?” If not then you should give credit whether it is in the acknowledgements or in the post when you share or by writing to the writer if you feel that is appropriate.

4. “Resistance” is a long-employed term that has come to mean anything from resisting tyranny, to resisting societal norms, to resisting negative urges and bad habits, and so much more. Is there anything you are resisting right now? Is your writing involved in that act of resistance?

I think my work is locked in combat with a kind of violently endorsed forgetting. So in my practice, to remember is a kind of resistance. It’s not my only tool but I think I am trying to teach myself in my writing to trust my memory (event based and simply physical) in ways that Refuse began to open and that I’m now working to push further. I’m also spending some time sitting with my relationship and understanding of beauty. Jericho Brown recently tasked me with reading all of Reginald Shepherd’s books before the new year starts and right now I’m parsing out a phenomenal essay of his on how Beauty and Justice can be the same because Beauty shows us the world as it ought to be. Now wouldn’t that be something, to resist empire by allowing myself to be governed by the concept of Beauty for a while? I’m giving that a spin, seeing how it fits, it may well stop feeling like a freedom practice tomorrow, it may run till the end of my life, who can know?

5. Tell us about one of your most memorable moments experienced within the Cave Canem community.

Those nights in the café area with my loves Quenton Baker and Natasha Oladokun are memories I will always treasure. I struggle to feel safe to struggle, to be unsure in front of many people because of the high level of pressure that I grew up under, and from the moment the three of us began posting up to get poems out before 10am in the Bin I knew that I was safe to doubt, and that’s the safest that I can be. The poems that emerged from that time, which aren’t in Refuse but are lighting my way to other desires, other questions, a different and perhaps better self, cannot exist without those laughs, debates, nights of boundless possibility.

6. What’s the most daring thing you’ve ever put into words?

“Do you believe me if I tell you I have only ever wanted to be worthy of my father’s grief?”

7. Have you ever written something you wish you could take back? What was your course of action?

I honestly can’t say that I have experienced the desire to take back something I have written. I can say though that I have feared the consequence of something true of mine having been read. When I write that I have struggled with depression, with suicidal ideation I know these are things that will have consequences for how I will be treated for the rest of my life. That’s scary, I wish at times it wasn’t so. But to wish that does nothing to make these things untrue, to not write them does nothing to make these things untrue; it only serves to make them heavier and more unbearable for me to hold them alone. I have shared a number of terrifying things in Refuse but nothing that has happened since those words began to be read can equal the pain and violence of having said nothing.

8. Post, stalk, or shun: What is your relationship to social media as a writer?

I understand the whole discourse around how social media is a distraction and how we need to be critical of thinking of ourselves and our work as part of a “brand,” that being said I like my social media accounts and the community I’ve built there. I have a free opportunity to share work that I love on a daily basis (I’ve been in the cut a little bit with my posting recently just because being a full time student, curator, teacher and being on tour means my energy is more thinly spread than ever before, but I’m getting back on a more regular schedule to just share what I’m reading) and that’s worth me holding onto. I also get that for some people the bad outweighs the good and they leave and that’s cool as well. My one big pet peeve in the whole thing is just when folk make a big show out of their opinion on it, these 10 page treatises to announce that they’re shutting down their account, I don’t see who that is for, I don’t think it accomplishes what folk think that it does.

9. Congratulations on the release of your debut poetry collection, Refuse, winner the 2017 Cave Canem Poetry Prize! What motivated you to utilize mythical figures as a way to speak to the book’s concern for Blackness, sexuality, family, and historical trauma, to name a few?

9. Congratulations on the release of your debut poetry collection, Refuse, winner the 2017 Cave Canem Poetry Prize! What motivated you to utilize mythical figures as a way to speak to the book’s concern for Blackness, sexuality, family, and historical trauma, to name a few?

As a kid I was a big Greek myths nerd, I had that big orange colored D’aulaires’ book and I actually used to read it in the back of the church my mom would take me to until eventually she let me stop going because I clearly just was not into it. I think what’s been pretty amazing in trying to mine my early memories and my adolescence to make sense of the life I am putting on the page, trying to shuffle the “I” in these poems into some kind of order is how long and how deep I had been building a system of knowledge and questions about the world that still guide me to this day.

Outside the fact that the Greek myths just make up some great stories I was fascinated by this space of impossibility that they occupied that I felt I occupied in a different way. Referenced or centralized in poems in the book are (among others) a boy who flew on wings of wax, a child born to human parents with the head of a bull, a man who died looking at himself, a man whose hell involves him constantly pushing a boulder up a hill he cannot finish mounting, and an impenetrable city ransacked by an undetected army in a horse. As a kid I loved these stories for their impossibility and was baffled that people could believe in this, but they couldn’t believe in a Biracial Black-Latinx kid from Logan Square who spoke more fluent English as a child than they did as adults and just wanted to make his parents proud.

10. Which poets have had the most profound influence on your writing and what are some lessons their work has taught you?

Vievee Francis not only saved my life but changed my life and every day her work and work ethic have taught me something about who I am working to be as both a mentor and in my work. Jericho Brown has taught me so much about how to be knowledgeable and fearless. Where would I be without Danez Smith’s voluminous imagination for where Black boys can be found? What about Derrick Harriell, Aimee Nezhukumatathil, Kiese Laymon (I know he doesn’t publish poems but he is teaching me so much about how to face things that it would be a lie to leave him out) who taught me among so much else how my poems can make a home for me anywhere. My best friends, George Abraham, Noel Quiñones, Nicholas Nichols, Itiola Jones, Miriam Harris, Quenton Baker, Gabriel Ramirez, Natasha Oladokun, and god the list might go on for hours. I could write a memoir of just what this small handful of folk have taught me, shoot maybe I will. But damn, ain’t it something to know you’re in a golden age for what you love most?