The PEN Ten: An Interview with Author and Translator Stefania Heim

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, PEN America’s Public Programs Manager Lily Philpott speaks with Stefania Heim, author of the poetry collection, HOUR BOOK (Ahsahta Press, 2019), and translator from the Italian of Giorgio de Chirico’s Geometry of Shadows (A Public Space Books, forthcoming October 2019).

1. As a translator, how do you navigate staying true to both the author’s original intention and work, and the rules of the language you are translating their ideas into?

The words “original intention” have sometimes been used as a limiting force in the reception of translations. I find the idea that a translation could ever be “true,” “direct,” or “transparent” to be misguided. Instead, the process of translation can really floodlight the differences in how languages operate, providing a thrilling creative problem to engage. My recent translation project, the writings of metaphysical artist Giorgio de Chirico, has been super interesting along these lines. Some of de Chirico’s sentences are mind-boggling, completely slippery—even in Italian, where you can push your syntax because word endings maintain connections. These ruptures, what he called “enigmas,” are a central feature of his paintings as well as his poetry. What is the relationship, either grammatically or spatially, between an iron artichoke, a train in the distance, and the goddess Athena? How can one translate syntactical ambiguity without merely adding confusion? It took me years to settle into de Chirico’s cadences, his rhythms, his images, his logics. To find a line in English that could sound the textures of his longings, which are so powerful. Sometimes it meant, for example, (and I really struggled with this choice) adding em-dashes where he just had strings of commas. The smallest translation choices can sometimes have the most impact. And then there was the matter of coming to terms with his other qualities—occasional facetiousness, pedantry, sonic play. Being a literary translator is something like putting a scrim made of someone else’s voice and vision over your own brain, learning to meet aspects of the world through their words.

“Being a literary translator is something like putting a scrim made of someone else’s voice and vision over your own brain, learning to meet aspects of the world through their words.”

2. What does your translation process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

When I start translating something, I experience an urge to charge through the work. I’m often stumbling over myself, conscious of making mistakes, swept up in the experience. I’ll lose the train of thought and add ellipses; my page will be marked with bolded and bracketed phrases and words—inconsistent shorthand for things to return to. I come out of this part of the process with a rough sketch of the whole work in English: That’s the essential first step. Then there is the slow steeping: going back over and over and over the text. Cross-referencing various Italian dictionaries, various English thesauri; going down internet rabbit holes of word usage; calling my sister, who is a translator of Italian queer theory and children’s books, for advice and commiseration; taking a break; returning. I don’t ever get back that propulsive momentum I have at the start, but I think that’s probably a good thing: The translation requires these different textures of work and thought. Finally, because I am also a poet and a scholar and a teacher, I always have other projects going at the same time—and their interrelations, the conversations that arise between them, are nourishing to me, and hopefully evident across the work.

3. What is one book or piece of writing you love that readers might not know about?

One of the main writers I focus on in my scholarship is 20th-century American poet Muriel Rukeyser. More and more people seem to be reading Rukeyser, acknowledging her as a founder of documentary poetry with her great “Book of the Dead,” turning to her as a model for literary activism and political resistance. But Rukeyser also wrote other radical, discipline-exploding works—novels, biographies, plays, translations, “story-songs.” My favorite is probably her 1942 biography of 19th-century physical chemist, Willard Gibbs, this completely abstruse scientist whose life and thought she animates by tracing its extensions into things like chemical warfare, and who she puts into surprising conversation with folks like Herman Melville and Emily Dickinson. It’s a strange and roving and really glorious book (which his family opposed, making her research difficult). Rukeyser was just not cowed by the barriers people put up between disciplines, people, aspects of our lives.

4. How can writers and translators affect resistance movements?

I think Rukeyser is a good model of a writer/translator who linked art and life in her commitment to social movements to transform the world. She talks about how poetry, with its focus on relationships and the interaction of information and emotion, can foster “a possible kind of imagination” with which to meet a world marked by violence, injustice, inequality, and oppression. Rukeyser was also an active participant in political struggles: from her first public act of being arrested as an 18-year-old who left college to attend and write about the trial of the Scottsboro boys, to her participation as a young journalist at the anti-fascist People’s Olympiad and witnessing of the eruption of the Spanish Civil War, to her work late in life as president of PEN’s American Center. Today, I’m especially inspired by efforts to link artistic practice and community activism, like the language justice and experimentation collaborative Antena, which was founded by writer/artist/translator/interpreters Jen Hofer and John Pluecker.

5. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

5. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

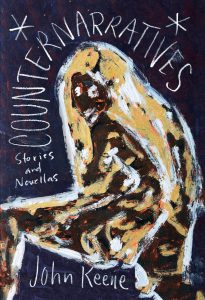

I just finished reading John Keene’s utterly brilliant and riveting Counternarratives. Keene’s sense of history, politics, intimacy, narrative forms, and language is so breathtakingly capacious and sharp at the same time. Keene is also an amazing translator (I’d argue that you can feel this in his stories and novellas) and his essay, “Translating Poetry, Translating Blackness” is also a must-read.

Next up for me is Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments. I love Hartman’s genre-challenging work, like Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route, so I’m particularly excited about encountering her voice again—the urgent and gorgeous forms she creates to write “at the limit of the unspeakable and the unknown.”

6. How does your identity shape your translations?

Probably the biggest reason that I am a translator is that I grew up in a multilingual family in which different people spoke to each other in different languages. My mother spoke to her parents in Roccolano, a Southern Italian dialect, and to her children in English; she spoke to her brother in English, except if their conversation somehow spun off of a conversation with their parents and then dialect colored some of the words; my grandparents spoke to us in more “proper” Italian, and we answered in English until we were older and switched to Italian. These were the general schematics, but, on Sundays, say, when we were all together around the table for hours, the languages all collided with each other at ever-increasing decibels. No one ever explained any of it, so my siblings and I rode the intersections of languages—their intimacies and angers, what was possible to feel and to express and to share with whom and how. So, when I translate someone like Giorgio de Chirico who had his own very peculiar experience of living and working between languages and between arts, an experience that was deeply shaped by his own lineage and family life, I bring this aspect of my experience very concretely to what I am doing, to how I make decisions, to how I feel my way through the works. This is true for my own poems as well.

7. What is the most daring thing you’ve ever translated? Have you ever translated a project you wish you hadn’t worked on?

For years, I have been attempting to translate (which is maybe an overly generous description of my struggle) the dialect poems of Gildo Funaro, a writer from Roccasicura, the small Southern Italian town where my mother grew up. Born in 1906, Funaro was a farmer with a fifth-grade education whose poems tell the town’s history—the occupying Polish soldiers and the girls who fell in love with them, the construction of the aqueduct that brought running water. These poems were public works: When the butcher and his nephew had a fight over land-ownership, Funaro apparently posted his poetic take on the squabble, and the town read it and memorized it. My mother remembers him holding court on his stoop across the street from her own, reciting poems. Funaro wrote in a language that is marked by various encounters. Sometimes his dialect bumps up against language from the United States, to which many townspeople had fled and were continuing to flee in order to escape the poverty of post-WWII life: Brucculine, Massaciuse, Nuova Giose. These lovingly articulated, butchered names are one of the things that make his poems so difficult to translate.

I think I’m classifying this as my most daring translation because I haven’t yet figured out how to do it. Because I don’t know how to imagine a public being interested in or understanding it. My great friend and mentor Ammiel Alcalay urges us to think about the literary worlds into which translated works are tossed (what works in the “target” language they are put into relationship with) and also how acts of translation can have material effects on the language and place the work comes from. I’m so personally caught up in this project that I don’t think I have a clear sense yet of the implications or consequences on either side. So, I answer my most daring project with one temporarily abandoned: an open wound.

“Translation is a practice. It can also be a rich and humbling way of participating in the world.”

8. What advice do you have for young translators?

To do it! Not to be daunted by a sense of piety or by anxiety about whether you’ve found the perfect text for you. But, at the same time, not to be arrogant and underestimate the task or the distance between you and the work you are engaging. Translation is a practice. It can also be a rich and humbling way of participating in the world. Read translations. Read about translation. Meet other translators. Talk about translation. As far as communities go, I’ve found translators to be a pretty generous, interesting, and wide-ranging bunch.

9. Which translators working today are you most excited by?

In 2003, when Jenny Kronovet and I founded the journal of poetry in translation, CIRCUMFERENCE, with book designer Dan Visel, we really felt that we were filling a need for something that did not exist. I can say, happily, that I don’t think that’s the case today. There are so many great presses and journals that are either dedicated to works in translation or committed to presenting translations alongside English-language and multilingual pieces—and I’m most excited about that collective energy. Jenny and Dan have actually started publishing full-length collections as Circumference Books, and their first title, Camouflage, by Lupe Gómez and translated from Galician by Erín Moure, came out this spring and is amazing.

There are many people—all of them writer-translators—whose translations and whose writing and thinking and talking about translation I always encounter with a thrill: John Keene, Ammiel Alcalay, Jen Hofer and John Pluecker, Jenny Kronovet (all of whom I’ve already mentioned), as well as Don Mee Choi, Mónica de la Torre, Sawako Nakayasu, Jennifer Scappettone, Gabrielle Civil, Michael Leong, Aaron Coleman, Pierre Joris, Anna Moschovakis, Matvei Yankelevich, Daniel Borzutzky, Johannes Göransson. There are more I am sure I am forgetting. . . . These people have been changing what it means to be a translator in our literary landscape, imagining new possibilities for the political and aesthetic contours of translation work.

10. Your most recent work is a translation of Italian artist and writer Giorgio de Chirico’s poetry. What initially drew you to de Chirico’s work? How would you describe his poetry to readers encountering him for the first time?

I realized recently that when telling people about my translation project, it was often more helpful to pull up a painting by de Chirico than to say his name. He is one of the most iconic 20th-century artists and I’m always stunned by how profoundly his images have entered the public imagination. He is sometimes called a surrealist, sometimes a metaphysical artist—he was adjacent to or involved in many big art movements of his time, was great friends with Apollinaire, had a falling out with Breton. The thing that is less known is that he was also a writer. I was introduced to his work by my friend, the wonderful poet Brett Fletcher Lauer. Brett was a fan of the art, had just read de Chirico’s Memoir, and had rustled up this cache of Italian and French poems on the website of the de Chirico Foundation. He sent them to me and asked: Are these any good? And they were! I loved them—they were so strange and haunting, both precise and unsettling. Here was this world filled with sulfuric cascades and smoking cliffs, statues walking of their low pedestals, revenants around corners, easels re-imagined as sailboats cast on voyages, all powered by this incredibly acute and visceral emotion. Brett’s next question was: Will you translate them? That was five years ago.

Stefania Heim received a translation fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts for her work on Giorgio de Chirico. A founding editor of CIRCUMFERENCE: Poetry in Translation, she is the author of the poetry collections HOUR BOOK and A Table That Goes On for Miles. She lives in Washington.