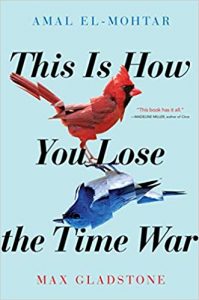

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Lily Philpott speaks with Amal El-Mohtar, author of This Is How You Lose the Time War (Gallery/Saga Press, 2019), with Max Gladstone.

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

The Hobbit by J. R. R. Tolkien. I read it when I was seven years old, and in addition to an engaging, delightful story full of riddles and poems that I could memorize and set to music, it gave me a methodology for becoming a writer. Somewhere in that first copy was a biographical note that explained Tolkien began writing poetry, then moved into short stories, then novels. I thought, “Oh, that’s how you become a writer,” and set about doing the same thing.

2. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

I think my writing navigates truth the way poetry navigates language. Which is to say, to echo and transform T. S. Eliot, if poetry breaks or dislocates language into meaning, fantasy breaks or dislocates reality into truth.

As to the relationship between them—I think it’s the relationship between tenor and vehicle in a metaphor. If I say “her face was an opal hour,” I’m conveying, truthfully, that my friend’s face is as beautiful to me, as luminous, as riveting as that hour of dawn where the sky makes one think of gleaming gems. Indisputably my friend’s face is not, in point of fact, made of opals; time is not literally reckoned in jewels. But in that moment where those meanings converge, where you allow that mornings and opals have something in common, that opals and faces have something in common, that my love for my friend provokes these tumbling cabochons of meaning, you have more truth than if I were to accurately describe my friend’s features.

“I couldn’t choose a favorite library any more than I could choose a favorite limb.”

3. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

It changes so much from project to project. Mostly, right now, as much as it grieves me to say so, my creative process is fueled by panic and anxiety, which is not great, not sustainable, and probably doing me harm. The work I’ve put aside in order to reply to these questions include a doctoral dissertation, a television pilot, end-of-term grading and next-term syllabi prep, all due within a few days of each other. It’s a lot, and the Mountain Goats’ “This Year” has become an uncomfortably persistent ear worm.

But a few days ago, I was visiting my family in the countryside, and my father and I were in the barn and he was showing me how to cut small rounds of wood from a piece of birch I’d pulled out of a woodpile. In the wood, there were shapes, patterns, that told the story of the tree, the story of this violence we’d done to it, and stories that had nothing to do with it, stories suggested only by this pattern my mind made into a rabbit or a fairy. And I turned these pieces of wood over and over in my hands and lost time to them, as I felt this wordless space in me filling up on the texture, the colors, the resonance of this wood in my hand, why one piece should feel different than another in some affective way I couldn’t explain. I felt myself wanting to rise to a different kind of work with it, a kind of communion—what could I add to it that wouldn’t take from it?

When I remember how long I spent holding the pieces of birch in my hand, I feel as if I’m drinking deeply, slaking thirst, and that’s my answer, I think. There’s a song lyric from an old Welsh song that I saw Anaïs Mitchell quote on Instagram—it’s translated as, the purpose and plan of the poet / is to go to the ends of the world. To feel myself traveling, whether across water or into the heart of a tree—that’s what I need in order to write.

4. What is one book or piece of writing you love that readers might not know about?

Travel Light by Naomi Mitchison. I will never stop recommending that book, not least because every time I do I feel I’m undoing a knot of distance between the time when I first read it (age 27) and the time I wish I’d first read it (age 7). I want children to read this book and fly through the world on the wings it gives them.

5. What is your favorite bookstore, or library?

5. What is your favorite bookstore, or library?

A year ago, this would have been an easy question to answer: Perfect Books in Ottawa, the small independent where I worked for five years during my late teens and early twenties. It’s still there and I still love it, and it has all my hometown loyalty. But since This Is How You Lose the Time War came out, and I’ve visited bookstores in other cities, had booksellers share their experiences of the book, all the people they’ve recommended it to, the art they’ve made from it—it’s a much more difficult proposition! Previously, the only variable I had for ‘favorite’ was ‘emotional connection to,’ and now I feel deeply connected to the places that have shown me wonderful hospitality: Trident Books and Brookline Booksmith in Boston, McNally Jackson Seaport in New York, The Savoy in Westerly, Category Is and Waterstones Argyle St in Glasgow. I feel my heart’s grown as my relationship with bookstores has changed from reader to author, and now “they made me tea” is as moving a proposition as “they have such a great SFF section.”

Where libraries are concerned, I need to believe they’re all one, that I’m loving all of them when I love one of them. I couldn’t choose a favorite library any more than I could choose a favorite limb.

“It comes naturally to me to write in fragments and in poetry, to build meaning between things, to question norms, defaults, certainties—to ask whose truth, and at whose expense.”

6. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

The last book I read was The Revisionaries by A. R. Moxon, which I reviewed for NPR. In the space between finishing this year’s book-reviewing and beginning the next, my husband and I are reading Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency by Douglas Adams to each other before bed, and it’s wonderful. We’re about 40 pages in and I have no idea what it’s about yet and I love it. Finding the time in a relentless schedule to read, not what’s coming out in six months, but what was published 30 years ago, feels like a weird gift. It’s simultaneously a retreat from the necessity of speaking one’s opinion and the opportunity to have new conversations in different contexts.

7. What do you consider to be the biggest threat to free expression today? Have there been times when your right to free expression has been challenged?

Is it boring to say “fascism”? I mean, it’s fascism.

Every time I attempt to fly cross the U.S. border, I feel like I’m being taken hostage. I become hyper-aware of my voice, my body, my appearance, my affect. It’s an abusive situation, a situation of attempting to imagine and anticipate everything about myself that might be provoking to the people who have complete power over my body, and then attempting to preemptively defuse it with compliance, good cheer, smiles. It’s a situation where when I’m detained I have to think, well, at least I’m not in a cage, at least I’m not being beaten—as if those are things to be grateful for instead of atrocities that have no place among us. Border guards have literally said to me, if you’re upset about this, you don’t know how good you have it. It’s a situation where I have to think, if I speak out about this, am I making things better or worse, and for whom? The second time I was detained, the worst time, I spoke to national media about it. The next time I tried to fly through that same airport, I was detained again, and the customs and border police made mocking reference to the media coverage and made it seem as if they were punishing me for it. I was able to get a Nexus card for about three months, before it was mysteriously revoked—mysteriously because they don’t have to tell you why they do anything, leaving you to guess, to wonder, to make yourself still smaller, still more compliant. I haven’t tried to fly into the U.S. for over a year even though I’ve never been denied entry outright.

In among all the necessary acknowledgement of how much worse things are at the U.S.’ southern border, the stolen and murdered children, the cages, the vicious cruelty, it does feel pointless and small to complain about having my freedom of movement curtailed in this way. But travel is such a constitutive part of me. I love to travel, I love who I am when I travel, I feel at my best when I am a visitor or a host, enacting one side or another of the sacredness of hospitality. Now, every time a far-flung friend invites me to visit, I have a moment of wrestling with grief before I answer.

“Let yourself finish things.”

8. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity”?

I’m fond of saying, somewhat flippantly, that the geopolitics of my inward self are complex. But it’s true, and it does affect my writing to have been raised with three languages and to have always been keenly aware of the ways in which they wielded or were subject to power. It does affect my writing to have always lived in places with contested national identities where that contest is partly expressed through language politics (at the border between Ontario and Quebec; in Lebanon, colonized by France; in Cornwall and Scotland). It comes naturally to me to write in fragments and in poetry, to build meaning between things, to question norms, defaults, certainties—to ask whose truth, and at whose expense.

9. What is the most daring thing you’ve ever put into words? Have you ever written something you wish you could take back?

There’s nothing I want to take back. Quite the reverse. I feel like there’s too much I hold back, too much tongue-biting for the sake of other people’s feelings. I feel like the most daring thing I’ve put into words is paradoxically the thing people most seem to forget about me: that I’m furious, that I’m never not furious. Me and the Hulk, except I can only change my shape to be smaller, neater, less threatening, in self-defense. There was a year where the only works I published were dense furious heartbroken fragments about borders that I cried while writing. One of them was “A Tale of Ash in Seven Birds,” in the collection The Djinn Falls in Love & Other Stories—in that I’m the hummingbird whose mouth “is a needle and a sword.”

10. What advice do you have for young writers?

Let yourself finish things. Cultivate compassion for your own work, for its flaws and limits. Let yourself love your work even as you labour to improve it. It came from you, it’s part of you, and what do you gain from despising it that you wouldn’t gain from nurturing it?

Amal El-Mohtar is an award-winning author, academic, and critic. Her short story “Seasons of Glass and Iron” won the Hugo, Nebula, and Locus awards and was a finalist for the World Fantasy, Sturgeon, Aurora, and Eugie Awards in the same year. She is the author, with Max Gladstone, of This Is How You Lose the Time War, a queer epistolary spy vs spy love story, and The Honey Month, a collection of poetry and prose written to the taste of 28 different kinds of honey. Her short fiction is forthcoming in BAX 2020 and has appeared on Tor.com and in magazines such as Lightspeed, Strange Horizons, Fireside Magazine, and the Rubin Museum of Art’s Spiral, as well as in anthologies such as The Mythic Dream, The Djinn Falls in Love and Other Stories and The Starlit Wood: New Fairy Tales. She reviews books for NPR and is the science fiction and fantasy columnist for the New York Times Book Review, is pursuing a PhD at Carleton University and teaches creative writing at the University of Ottawa. Find her online at amalelmohtar.com, on Twitter @tithenai and on Substack at amal.substack.com.