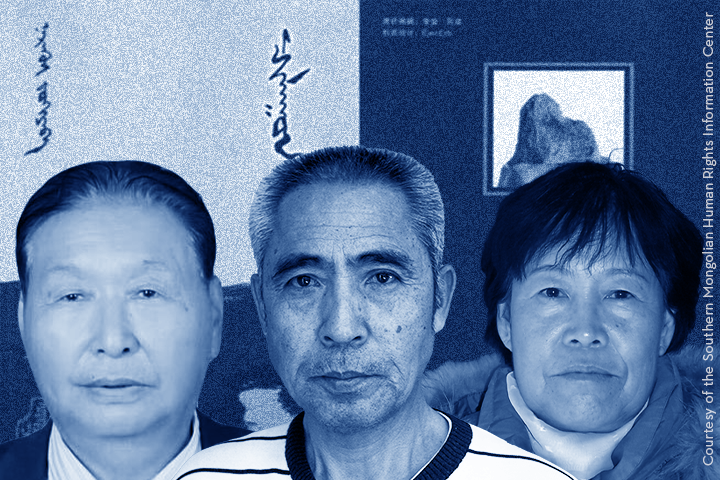

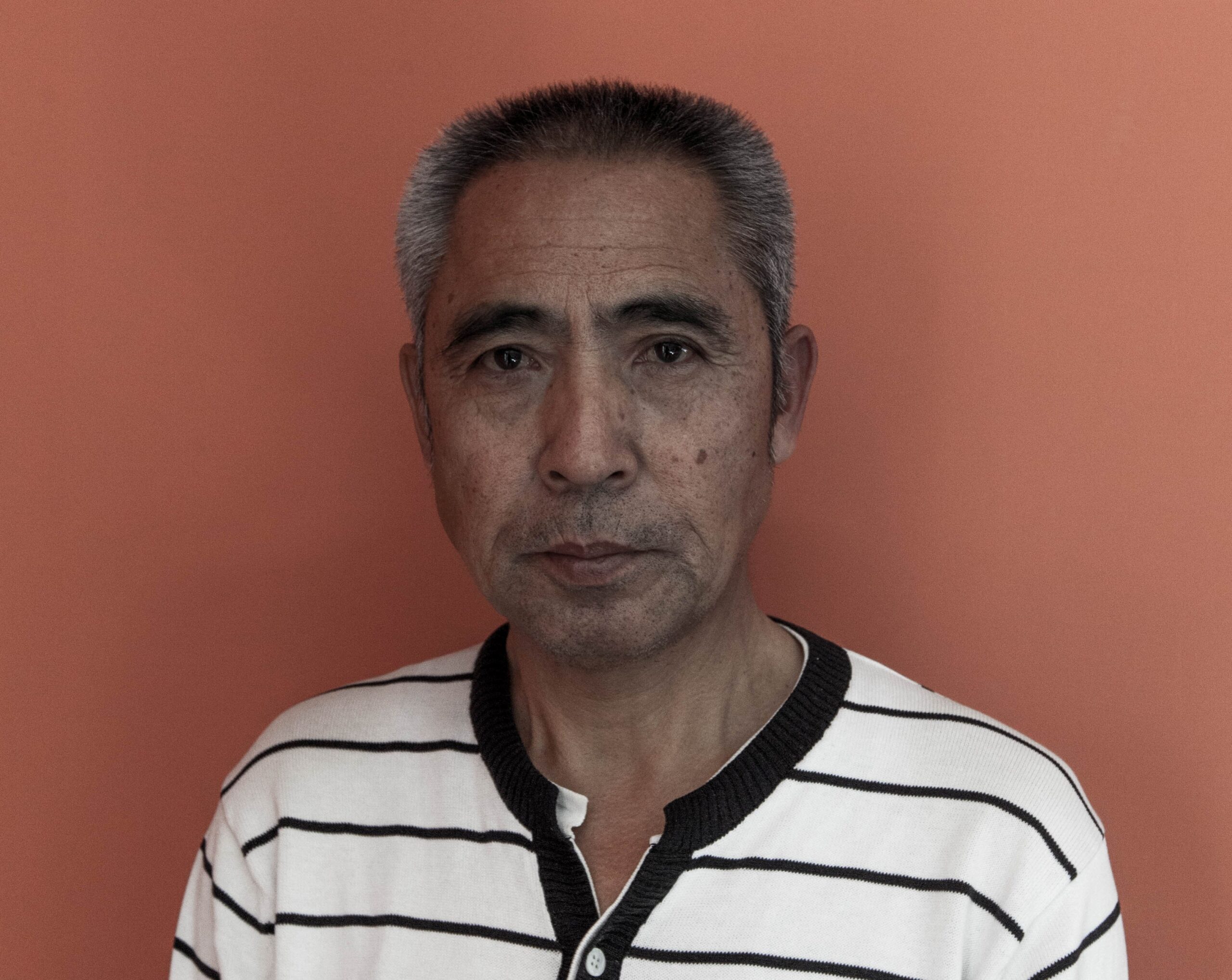

It has been one year since anyone saw Hada, a Mongolian writer, bookseller, and activist who was disappeared from his hospital bed on February 6, 2025 by Chinese state agents.

Hada had been under house arrest when he suffered catastrophic organ failure and was rushed to the hospital by the security officers who had been monitoring his every move since his release from prison in 2014. His catastrophic health problems came as a result of decades of imprisonment, surveillance, and harassment because of his writing and his activism for Mongolian rights.

He was first arrested in 1995 for charges related to his activism, and later sentenced to 15 years in prison, during which he was reportedly tortured. While he was behind bars, his wife Xinna continued to run the Mongolian studies bookstore and its reading club, which they owned together. In 2001, the bookstore was temporarily shut down by authorities and the more than 200 students who were members of the reading club were questioned. In 2010, authorities shut down the bookstore permanently.

Even when his sentence officially ended, authorities detained him for another four years. Upon release in 2014, he was put under house arrest and around-the-clock surveillance until his disappearance from the hospital a year ago. Xinna and their son Uiles have also been repeatedly arrested, harassed, and surveilled.

Hada is one of many Mongolian writers who have suffered under the constant repression by the Chinese state. Our new report with the Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, “Save Our Mother Tongue”: Online Repression and Erasure of Mongolian Culture in China, documents how China is systematically trying to wipe out Mongolian language and culture. Writers like Hada have long played an indispensable role in protecting and developing this culture. They ensure Mongolian stories and histories are told on their terms, and that their language is visible and dynamic. For this, writers in China, especially writers from minority groups, have faced persecution – and even if they are released from prison, they are not free.

Huuchinhuu Govruud was a Mongolian writer and essayist who managed and edited the cultural sites and discussion forums Nutag, Ehoron, and Mongol Yurt Forum. In November 2010, she was arrested for writing that Mongolians should celebrate the scheduled release of Hada. She was detained, placed under house arrest, beaten by local police, and cut off from the internet, her phone, and postal services. The internet forums she administered, which discussed Mongolian culture, history, language, literature, and their rights to their land, were all shut down, and her books banned. She died of cancer in 2016, still surrounded by Chinese state security personnel.

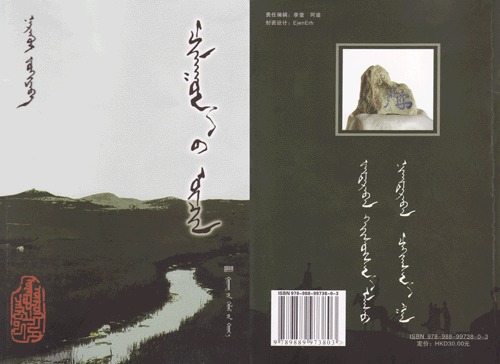

Lhamjab Borjgin is another writer targeted with detention, surveillance, and intimidation. Borjgin is a Mongolian writer and historian who challenged state narratives through work like his 2006 book China Cultural Revolution. The book pushes back against official records of the killing of Mongolians during the cultural revolution through a compilation of survivors’ oral histories. In 2018, an audio version of the book spread widely online and In 2019, he was arrested and sentenced to one year in prison for his writing. Following his release in 2020, he was put under “residential surveillance,” a form of house arrest.

In 2020, the Chinese authorities also escalated their campaign to repress Mongolian culture by implementing a policy replacing Mongolian-language instruction with Mandarin Chinese. The resulting protests were met with a brutal crackdown, including internet shut-offs and thousands of arrests.

Authorities placed 8,000 – 10,000 Mongolians in some form of police custody and many writers – including Borjigin – were specifically targeted and prevented from accessing the internet or posting online. The Chinese government also disconnected protesters from one another by shutting down Mongolian messaging platforms and compelling platforms to delete posts and videos about the protests. These videos were, thankfully, preserved by human rights organizations, otherwise we would have no evidence of their existence.

In an already-censored environment, Chinese authorities have intensified control over what Mongolians can consume, including exerting pressure beyond its borders. Following the protests, nearly 89% of sites using Mongolian script – including sites highlighting Mongolian literature and connecting Mongolian writers – have been erased. Earlier this year, the Network of China Human Rights Defenders reported on the removal of Chinese-language books about Uyghur, Tibetan, and Mongolian history from a popular online bookstore. Human Rights Watch has also reported on Chinese police reaching across their borders and harassing Mongolians who have begun book clubs in Japan.

Borjgin, who fled to Mongolia in March 2023, was later kidnapped from his residence in exile and forcibly deported to China. His whereabouts are unknown today.

Governments imprison writers for the same reason they criminalize minorities and minoritized languages, punish reading, and ban books: to silence stories, erase history, and consolidate control.

PEN America’s Freedom to Write Index documents the number of writers jailed for their words around the world annually. In 2024, the number of writers jailed in China rose again, jumping from 107 cases to 118. Just under half of the imprisoned writers during 2024 were Uyghur, Tibetan, or Mongolian, often arrested and imprisoned for vague charges that allege “separatism.”

Removing access to stories, whether ripping books from shelves, scrubbing them from the internet, or attacking the writers behind them, does not diminish their importance, nor peoples’ appetite for them. In March 2023, Lhamjab Borjgin shared with the Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center that despite the removal of Mongolian textbooks from bookstores and libraries, teachers found a way to keep some by “hiding them in nooks and crannies.”

In a 2015 essay, Hada wrote “Resistance, while riskier, offers hope.” Today, the creative community should ensure Mongolian stories and language are not hidden. They should partner with Mongolian cultural and linguistic initiatives to make Mongolian culture visible, support independent reporting and make space for Mongolian voices in platforms and publications, and actively speak out against Chinese government overreach into people’s culture and language.